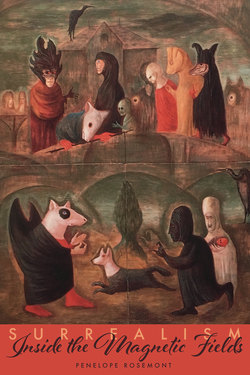

Читать книгу Surrealism - Penelope Rosemont - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавлениеone

The Magnetic Fields, Cinema, and the Penetrating Light of the Total Eclipse

“Surrealism.”

“What did you say?”

“I said, Surrealism.”

“And what does that mean?”

“Nothing . . . . Everything.”

“But what is it?”

“Nothing . . . And yet, it is something.”

“And what does this something do?”

“Spreads . . . . . . . spreads monsters of consciousness.”

Surrealism has spread its images and poetic spell everywhere. Newly invented, in 1919, its first step, the text Magnetic Fields is a mental experiment . . . Yet it has always existed, but was understood only subliminally. It could be called the language of the Unconscious. André Breton and Philippe Soupault working together produced its first text. They did this collectively from pieces of dreams and ragtag realities, from murdered moments and twilight streets, from anything and everything that flashed into their minds. Breton later expressed this new idea as “Beauty must be convulsive or it will not be.” Surrealism sought to rescue the Verb and refresh language, and thus, refresh thought itself. The image in the mind is provoked by language. Thus new images are created, loosed upon an unsuspecting world, the possibilities swell. The very idea of beauty is challenged and overthrown. Secrets of the Unconscious laid bare.

Surrealism evolved with cinema. André Breton, Jacques Vaché, other Dadaists, and soon-to-be surrealists were thrilled by the cinema. Its darkness, its dream-like quality, its promise of power, its satisfying Wish Fulfilment. They chose to experience it in their own way. They would spend a few minutes at one theater and then go onto another and then onto the next. Producing a surrealist game of it, a type of mental Exquisite Corpse.

Breton and Vaché had both been mobilized for WWI. They saw together Les Vampires, a serial by Louis Feuillade made in 1915. In the film, a Parisian gang of criminals led by a beautiful woman dressed in a skintight black leotard terrorizes Paris. Probably inspired by a group that was part of popular consciousness: the Bonnot Gang, anarchists, known as the “Auto Bandits” of 1912. They escaped capture at high speed in autos, being among the first to take advantage of the new motor car. Somehow Feuillade twists our morals and puts us on the side of the outlaws. Breton wrote, “It is in Les Vampires that one must look for the great reality of this century.” In his preface to Vaché’s War Letters he writes, “the playbill: They are back—Who?—The Vampires, and in the dark auditorium, those red letters that very night.”

The series of books Fantômas began in 1911, and ran to 32 volumes. Fantômas is the Master Criminal. “Nothing is impossible for Fantômas!” These novels were written using an automatic method, dictated at high speed. Pierre Souvestre would write one chapter, Marcel Allain the next after seeing only the last page. Every chapter was a cliffhanger. A 300-page novel would take them five days to write.

Soupault commented in La Révolution surréaliste that these were written at such a high speed that they must reveal the inner workings of the mind. “I challenge any author anywhere in the world to write, or even more to dictate, fourteen hours a day, day after day, without finding himself under the total control of absolute automatism.”

Breton’s closest friend, Jacques Vaché, who shared Breton’s hopes and dreams, in a letter from the WWI field of battle wrote, “What a film I shall make!—with crazy motor-cars, you know, crumbling bridges, and enormous hands crawling all over the screen toward some document! . . . Useless and inappreciable! . . . With colloquies so tragic, in formal attire, behind the listening palm-tree!—And Charlie Chaplin of course, with frozen smile, his eyes deadly. The Policeman forgotten in the trunk!!!”

And what to do: “I shall also be a trapper, or thief, or a prospector, or a hunter or a miner, or a welder. . . An Arizona Tavern (Whisky—Gin and mixed?) and beautiful forests to explore, and you know those fine riding-breeches and some machine-guns, and well-tended, beautiful hands with diamonds rings—All this will end in conflagration, I tell you, or in a salon, Fortune made—Well . . .”

Speaking frankly to Breton, “How am I, my poor friend, going to put up with these last months in uniform? . . . (I’m told the war is over) . . . I am truly tired out. . . and THEY are suspicious . . . They suspect something—As long as THEY don’t debrain me while THEY still have me in their grip! . . . I read the article on cinema. . . There will be some amusing things to do, when unleashed and free.”

But Vaché died, a suicide, an accident perhaps, on January 6, 1919, after having been demobilized. Breton, who knew him best, commented that Vaché loved life too much to kill himself.

Breton wrote to Tristan Tzara in Geneva on the 22nd of January 1919 enthusiastic about Tzara’s 1916 Dada Manifesto, mentioning Vaché, who had died two weeks earlier, would also have wanted to be part of Dada. Mid-January, an ill-fated Spartacist uprising was put down in Berlin. In March, the first issue of Breton’s anti-culture magazine Littérature appeared. In Munich, April 1919, some radical Bohemians and Gustav Landauer took over the state. This lasted five days and was called the Munich Soviet Republic. It ended tragically with most killed. Eclipse: May 29, one of the great history-making scientific events. Headlines blared as the total eclipse observed by Arthur Eddington proved Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity and truly ushered in a new world. In April, May, Breton and Aragon published the Poésies by Lautréamont. They had discovered the only existing copy in the National Library. Earlier, Soupault had discovered Lautréamont’s Maldoror in the mathematics section of a bookstore in 1917. A letter by Vaché was published in Littérature in July. August saw the publication as a book of Vaché’s War Letters. In 1920, when Magnetic Fields appeared, it was dedicated to Vaché.

Considering the war, Vaché’s death, the influenza epidemic, it is not surprising what Magnetic Fields expresses. The mind struggles there, and all of the outpouring of emotions, long pent up, are expressed . . . meaningless, fraught with meaning . . . the beginning text of surrealism, an intermix of Chance, Play, Intuition. They called it “pure psychic automatism.”

What does it provoke? For me, the great experiments of animal magnetism in Paris. Mesmerism! Hypnosis. Charcot and Freud’s exploration of mind. The Passional Attraction of Charles Fourier that is the sublime motivation. Attractions that are proportional to destinies.

But there is also a do or die attitude, taken seriously, taken casually, dismissed, as soldiers learn to dismiss life. The overwhelming chaos of war and loss and a fierce attempt to choose to live. The collisions of chance by which we live or die. That play with us, that are played with, it’s all in play, it’s all a game, life itself. . . . We’re only players on a vast stage . . . But . . . do we get to pick the stage?

Does Breton wish to create a magnetic field for language: surrealism?

“Prisoners in a drop of water, we are everlastingly still animals.”

“All of us laugh, all of us sing, but no one feels his heart beat anymore.”

“The immense smile of the whole Earth has not been enough for us:

we have to have more deserts, more suburban cities, more dead seas.”

“Each transit is saluted by the departure of giant birds.”

“Those charming codes of polite behavior are far away.”

“No one knows how to despise us.” (Magnetic Fields)

And myself, as a disaffected teenager I discovered the phrase, “Elephants are contagious!” A slogan penned by Paul Éluard. I laughed for a week. And passed it on, whispered it to friends. In 1964, when I was 22 years old, I encountered the surrealist-oriented militants of the Anti-Poetry Club at Chicago’s Roosevelt University. It was the first group I encountered I felt I belonged in. Sometimes I call us, with good reason, “anthropology students run amok.” We were anthropology students, studying with St. Clair Drake but with ideas of changing the world, and we were planning to do it from our obscure bookstore on Armitage Avenue. The initial group was Franklin Rosemont, Bernard Marszalek, Tor Faegre, Robert Green, and myself. Soon joined by Joan Smith, Simone Collier, Lester Doré, Lionel Bottari, Larry DeCoster, and Dotty DeCoster. Then, in 1965 rather abruptly, we headed for London and Paris driven by a dream of finding the electricity created inside the Magnetic Fields.