Читать книгу Charlotte Mew: and Her Friends - Penelope Fitzgerald, Simon Callow - Страница 9

CHAPTER THREE Lotti

ОглавлениеLOTTI, everyone said, had changed. She was still unpredictable and passionate and could still, if she wanted to and was in the vein, make everybody laugh until they cried. But the innocent desire to show off had failed her. She was often fierce with strangers. Her wild impulses no longer turned all the same way, outwards, to meet the world. Once she had been driven to wild happiness at any kind of celebration; now, it seemed, she had hardened. ‘It is a legend in my family’, she wrote, ‘that at festive seasons I am cynically indifferent to the pile of good wishes and parcels that come my way – but this may merely be a self-protective mask for the “emotional nature” which you insist on crediting me with … I am credited with a more or less indifferent front to these things – the fact is they cut me to the heart.’ The storm within had to have an outlet. She needed exhausting music, not her piano pieces, but Wagner, Tannhäuser above all. Meanwhile the silver cross round her neck (and the gold one on Sundays) was an outward sign that she had entered an Anglo-Catholic phase, and, with her mother and Anne, was attending Christina Rossetti’s church, Christ Church, Woburn Square. But whereas Anne continued in the same faith till death, Lotti suffered from all the spiritual nausea of belief and unbelief. Her family were at a loss, her friends still more so. They knew only that Lotti was very brilliant, and out of them all must be the one who would do great things. In appearance she was still a tough, delicate miniature – her boot size was number 2 – her smallness making an immediate appeal, wherever she went, to the toy-loving human race. Her voice had become rather chancy, sometimes hoarse, like a boy’s breaking, but very flexible, and fascinating to listen to.

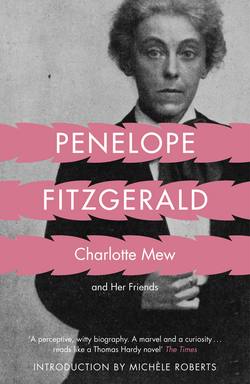

Vestry Hall, Hampstead (now the Old Town Hall) by Kendall and Mew. A drawing by Fred Mew.

Freda was still a little girl, Anne continued placidly at the Gower Street School after Miss Harrison had left. Charlotte was now the daughter at home. Although Fred, as has been seen, was called upon as head of the household in all business matters, and when it was necessary for someone to be ‘spoken to’, it is doubtful if he saw much of his daughters. Still a complete failure from the point of view of gentlemanliness, he had had to put all his energy for some time past into the affairs of Kendall and Mew.

H.E.K. relied by now almost entirely on Fred. Old Kendall had died in 1875, leaving very little (he had entertained lavishly all his life) beyond the Brighton property, and in The Builder’s words, H.E.K. ‘during his own later years, was greatly assisted in his professional engagements by his son-in-law Mr Frederick Mew’. The two of them were associated at Gordon House, Isleworth, for the Earl of Kilmorey; at Madingley Hall, near Cambridge, at Staunton Harold, for Earl Ferrers; and, in 1876, in the new Hampstead Vestry Hall. So far, so good. This commission should have been the high point of the firm’s success, ensuring a prosperous future for Anna Maria and the Mews.

Hampstead in the late 1870s was a rapidly extending rural suburb, with a population of 40,000. The Hall (now the Old Town Hall, Rosslyn Hill) was intended to house the sixty Vestry members in dignity and comfort, but it was also to be ‘a centre of social life and healthful activity’. By this it was meant that the Vestry could recover some of the expenses by letting it out for concerts. From the outset it was stipulated that the main hall must hold 800, and, although the total costs were not to exceed £10,000, the building must be ‘appropriate’ and ‘worthy’.

In April 1876 the contract was offered for competition. Kendall and Mew’s entry, under the disarming motto Cavendo tutus (caution means safety) was accepted by a majority. Their design was for a handsome edifice in one of their ‘Italian’ styles, faced with red brick and dressings of Portland Stone, centrally heated and lit by gas. But almost at once the familiar unpleasantness began. ‘Sir,’ wrote an unsuccessful competitor, a few weeks after the award, to the Hampstead & Highgate Express, ‘while inspecting the drawings for the above, prior to the decisions of the Vestry, my attention was called to a gentleman with a foot-rule, pointing out the merits (?) of the design marked ‘Cavendo tutus’ to all comers. Upon speaking to him, I discovered he was a vestryman, and he stated to me that he knew whose design it was, and had seen it prior to its being sent in … ‘Cavendo tutus’ appears to have ignored all the conditions – the large hall showing to hold about 400 people (if I mistake not) instead of the 800 required.’ This was quite true, and nobody believed, either, in the accepted estimate of £9,375. The suggestion was that H.E.K., as Hampstead’s district surveyor, had got his foot in first. Criticism grew louder when the work was held up for month after month. The Vestry, obliged to meet in one of the dining-halls of Hampstead Workhouse, were restive. By midsummer the partners had to issue a statement ‘that though the work had not been proceeded with so rapidly as it might have been, the architect was of the opinion that this was all the better for the building’. This sounds more like Fred than the suave and experienced Kendall, who in fact, at the age of seventy, had entered the slow deterioration of his last illness. Reports and certificates were no longer dated from his office, which was closed, but from 30 Doughty Street. With his wife Maria and daughter Mary Leonora, he had moved from expensive Brunswick Square to 34 Burlington Road, near Paddington railway station. Where had the money gone, from the long series of country mansions, Gothic parochial school and Domestic Elizabethan lunatic asylums? On 10 August 1878 Fred was obliged to apply, on the partners’ behalf, for ‘£100 on account’, suggesting that they were operating on a very small margin.

By the end of the summer the main building was complete except for the boundary walls, and the Vestry, who had been ‘crouching’ in the half-finished rooms, emerged and passed a resolution that the money had been well spent. This, however, was in the face of public complaints about the delay, the small size of the hall, the bright red Bracknell brick which was ‘brought before the eye to a painful degree’ and which, without the stone dressings, would be ‘unbearable’ and make Hampstead’s residents dizzy. Most unfortunate of all was the fact that the builder had already had the date carved over the entrance, 1877, whereas the grand opening had to be delayed until November 1878. At the celebration dinner a number of healths were drunk ‘three times three’, but not Kendall and Mew’s.

It seems clear that the Kendall women, who had always treated Fred as an uncouth interloper, blamed him for this and every other misfortune, and refused to admit his difficulties at the end of twenty loyal years of partnership. Although Fred was only an executor of H.E.K.’s will and not a beneficiary (unless he survived Anna Maria), there was a strong feeling that he was after the money. This appears from Maria Kendall’s will, made on 17 April 1883 to dispose of her legacy from her own family, the Cobhams. One-third was to go to Anna Maria ‘for her sole use and benefit separate and apart from and exclusive of her said husband Frederick Mew, and that she may hold and enjoy and dispose of such share in the same manner as if she were unmarried’. The legend that Fred was a monster of selfishness was now well established. Charlotte, sadly enough, the little girl for whom he had made the doll’s house with bow windows, grew up to believe the legend, and repeat it.

In 1885 H.E.K. died, leaving a personal estate of £616 10s. His widow, with Mary Leonora, went to live permanently in Brighton, while Fred was confidently expected to keep the firm going, and maintain them all in comfort. Very likely the family did not know how things stood. Gissing’s Dr Madden in The Odd Women, who considers that ‘women, young and old, should never have to think about money’, and fails to take out any insurance, was a not unusual type of professional man. And probably Fred could not bring himself to tell them the truth, which was that for all his size and presence he was a follower, not a leader. After the death of his beloved old master, he lost direction. For years he had been doing virtually all the work, in the office and on the sites, but always as Kendall wanted it.

During Kendall’s long illness Fred had designed or part-designed a few private houses, a bank at Aldershot (1882), and (his most important commission) the Capital and Counties Bank in Bristol (1885), ‘with details somewhat Greek in character’. In the same year the Hampstead Vestry, perhaps surprisingly, had asked the partners to undertake an extension to their Hall along the Belsize Park frontage. Fred in fact carried this out, but this is the last commission of his that I have been able to trace. The heart had gone out of him.

He was, admittedly, cowardly in not telling his wife that the firm’s work had declined and that Elizabeth Goodman should be making do and patching even more, rather than less. After the commission for the Vestry Hall extension, he even agreed that the family should look for a larger house. Anna Maria no longer had Brunswick Square to fall back upon. She needed a ‘better address’. In 1888 the Mews moved to 9 Gordon Street, just where the street joins, or once joined, Gordon Square. It was a much taller house than Doughty Street, four storeys above the basement and its sunless area, and it had a piano nobile of spacious rooms, elegantly railed off with a wrought-iron balcony. The whole street had been built by Thomas Cubitt for the Bedford Estate before he moved on towards greater triumphs in London’s West End. This would have recommended the house to Anna Maria, since Mrs Lewis Cubitt was the most distinguished of her aunts. It kept up the connection, and this was precious to her. Fred bought the end of the lease, with another twenty-four years to run.

Elizabeth Goodman settled them all in. The semi-invalid Anna Maria must of course be spared as much trouble as possible. Wek, her parrot, who had been with her since the days in Brunswick Square, was introduced, under protest, to his new home. Kendall’s picture of the Shining City was hung in the front drawing-room, next to the portrait of Anna Maria as a young girl. Fred’s office was on the ground floor. But Gordon Street was never either a happy or a lucky house. After the move, Fred pinned his hopes on Henry. The dashing, promising son must have been more than a help with the office routine, and a much-needed new life in the business. He was a refuge in a house full of women. But now, in his early twenties, Henry began to show unmistakable signs of mental breakdown. The illness was what was then known as dementia praecox, because it was thought to attack adolescents and young adults in particular. It would be called schizophrenia now. Fred was advised that there was no possibility of a cure, and for the rest of his life Henry was confined, with a private nurse, to Peckham Hospital.

The history of mental weakness was not on the Mew side, but the Kendall. Never mentioned in public was the reason why Edward Herne Kendall, Anna Maria’s elder brother, had failed to join the partnership after his training, and why in fact he had no occupation of any kind. Edward was not a schizophrenic, simply a borderline case who might from time to time need looking after, and who could never be trusted with his own affairs. When he became completely irresponsible his money was saved up for him and invested until he ‘came back’. Mary Leonora, also, was not strong in the wits, or, at least, foolish, and it was the constant fear of her mother, Mrs Kendall, that she might be ‘got hold of’ in some way, and left penniless. In all probability, Henry Mew’s tragic illness had nothing to do with his Kendall uncle and aunt, and yet the suggestion remained that it had. Meanwhile the fact that there was no insanity to be traced in Fred’s family was likely to make him more, and not less, to blame.

The family at 9 Gordon Street was reduced, after so many hopes, to three daughters. Elizabeth Goodman acted as the family’s consoler. ‘There was nothing conscious or masterful about this,’ Charlotte wrote, ‘it was simply the gentle, irresistible mastery of the strongest, clothed with an old-world deference.’ The son was as good as lost, but the youngest, Freda, was doted upon. Even her name had been a romantic flight, distinguishing her from all the rest. Fred and Anna Maria, whatever their discords, both combined to love and spoil this exceptional little girl, who grew into adolescence still beautiful and brilliant. This would be about the time when Henry Mew made his sad exit into separation and silence.

Then, early in the 1890s, Freda followed him. She began to show recognizable symptoms of schizophrenia, then, like Henry, broke down beyond recall. Poor Fred asserted himself for almost the last time, and insisted that she must not be kept in London, but sent back to the Island, within reach of the Bugle Inn and the farm. Freda lived for another sixty-odd years as a paying patient at the Whitelands Hospital, Carisbrooke, without ever recovering her sanity.