Читать книгу Girl in the Window - Penny Joelson - Страница 11

Оглавление4

I can’t get up the next day or the next and, apart from crawling to the bathroom next door, I don’t try to do much else. The only other thing I stand to do is draw the curtains – open in the morning and closed at night. I know Mum would do it, but I want to look out – remind myself that there is a world out there.

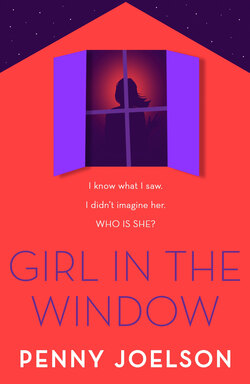

This evening I look across the road and I can see a light on upstairs in the room opposite mine at number forty-eight. Someone is drawing the curtains there too. I briefly catch a glimpse of the figure but it doesn’t look like the man or woman who live there. It’s someone skinnier – a girl, I think. Was it her I saw in the window the other night, when the woman was abducted?

Now that I’ve been downstairs, my small bedroom is feeling even smaller than it did before. Lying in my bed, all I can see is the pale pink walls, painted when I was six, matching pale pink curtains, my wicker chair by the window, and a white desk and white wardrobe against the wall. On the wall is a small picture – a Polish village scene with a girl outside a church – that once belonged to my grandmother. And I have a tiny bedside shelf for my glass of water, phone and clock.

My duvet cover makes my room look more grown up – it’s silky pink with splashes of purple on it. There’s no room for my cello in here and maybe that’s for the best. It’s downstairs in the corner of the lounge and I am glad not to have to look at it and be constantly reminded that I can’t even pick it up, let alone play it.

Marek’s room is a little bigger than mine and Dad asked if I wanted to swap when Marek went to uni. But I didn’t – his room is painted black and orange, which would have taken many coats of paint to cover. And anyway, I didn’t want to think of Marek as having left home. I thought he’d be back in the long holidays, and even when he’d finished uni. I’m still glad his room is as he left it, waiting for him to come back.

I lie in bed, sleeping, listening to podcasts and audiobooks on my phone, meditating and thinking of ideas for stories. Then my mind turns to Josh. I like him so much. Only Ellie knows how I feel. I wish I’d had the courage to say something to him while I was well. I kept hoping he’d speak to me, but maybe he’s shy. He’s in the year above me but we were both in the orchestra – I could have said something then, but I didn’t. He’s probably going out with someone else by now and I wouldn’t blame him. He has no idea how I feel about him, so it’s not as if he’d be waiting for me to get better.

I get a message from Marek. He’s seen Mum’s photo of me sitting downstairs, and his message is full of excited smiley emojis, along with a photo of a frozen pizza, with the caption ‘My job is cheese sprinkling!’

Dad had better not see that!

I reply, telling him about the writing competition, and get more excited smiley emojis back. I think about telling him about the abduction, but I’m too tired to text that much.

I lie back and think about the award ceremony again. I just have to get well enough to go. I must.

A few days later, I’m feeling a bit better. I don’t feel like attempting the stairs again but I’m mostly OK being out of bed. I sit on the floor and open my chest of drawers, just for something to do. There I find the Get Well card with the cheerful yellow sunflowers on it. I open it and run my finger over Josh’s signature. I wonder if he ever thinks about me now. The card is also signed by the other twenty-four members of the orchestra but his is the only name in there that really matters to me. He’s an amazing violin player and when we’d finished orchestra practice he used to meet my eyes sometimes and smile. I’m sure something would have happened between us one day.

I put the card back in the drawer. My legs are hurting from sitting on the floor but I don’t feel too bad otherwise so I stand stiffly and sit on my wicker chair by the window, looking out. I still feel like I’m on a boat – but it’s a gentle rowing boat now. I watch as the woman at number forty-eight comes out, bumping the grey buggy with a rain cover over it, down the steps to the street. She hurries off up the road and I glance up to the window above. There’s no one there.

It’s raining heavily now – big drops streaking down my window like bars, reminding me of the prison my room has become. It’s hard to see through the rain, but I try. There’s no one looking out across the road. Cars splash past in the big puddle by the bus stop. The haziness makes everything seem unreal. It’s like the rain is trying to wash away what I saw – washing it all away, wiping the slate clean, a fresh start.

I can’t remember it clearly now. Maybe none of it happened at all. But if it did, what happened to that woman? I can’t help wondering about her.

It’s a week later when I pluck up the courage – and have the energy – to go downstairs again. And it’s fine! I stay for a whole meal, and also get back upstairs by myself too. I do it again, each day stretching it out a little longer, and I don’t have any ill effects.

I feel full of hope – I’m finally getting better – and I want to do more.

Mum comes into the living room, waving a parcel at me. ‘I’m just popping next door,’ she tells me. ‘The delivery man left it here this morning, when he couldn’t get an answer.’

‘I could take it,’ I offer.

Mum looks at me in surprise. ‘Are you sure you feel up to it?’

‘It’s only next door. And it would be good to get outside. Let me, Mum. I’ll be fine.’

‘OK,’ says Mum, but she’s looking very doubtful.

‘Is it forty-three?’ I ask her. ‘Won’t they be at work?’

‘No – forty-seven,’ says Mum. ‘Mrs Gayatri.’

‘How did she manage to miss a parcel?’ I comment. ‘She never goes out.’

‘She does sometimes,’ Mum says with a shrug. ‘Perhaps she was having a nap or just didn’t hear the door.’

‘OK. I won’t be long,’ I tell Mum.

It’s weird putting on outdoor shoes when I’ve worn nothing but slippers for months, and I’ve rarely been out of bed enough to even need them. My shoes feel hard and uncomfortable in contrast.

‘Put your coat on,’ Mum fusses. ‘And your scarf.’

‘It’s only next door!’ I say, but I do it anyway.

I take the small package and step out of the house – so happy to actually be outside. I wonder what Mrs Gayatri has ordered. It’s rectangular but not heavy. We don’t see our neighbours very often. There’s a young couple on the other side, at number forty-three. We only know their names because they sometimes have parcels delivered while they’re at work, and Mum takes them in. I don’t remember Mrs G ever having a delivery before, though.

We don’t see her much either, though I used to sometimes see her weeding her front path. She’s the only person round here who has pots and flowers and bushes out the front. She’s not very chatty, but she always has a smile and says hello if we pass her. Of course, since I’ve been ill I’ve only seen her from my window, on her rare walks up the road to the shops.

The cool breeze makes my cheeks tingle as I stand on Mrs G’s front step and ring her bell. I feel a buzz of excitement and breathe in deeply. It’s one step closer to normal life. There’s no answer and I wonder if the bell is working. I wait a few moments, try again and then resort to the old-fashioned lion’s head knocker. I listen but can hear no sound from inside. The lion’s face is snarling at me and I’m about to turn back home because my legs are beginning to throb, which sometimes happens when I’m standing still. Then I hear a small sound – a definite movement from inside.

‘Mrs Gayatri?’ I call. ‘It’s me – Kasia from next door. I have a parcel for you.’

The door opens and Mrs Gayatri peers out nervously. She seems more shrunken and wrinkled than I remember, but her eyes are soft and kind.

She smiles. ‘Hello, dear. I haven’t seen you for a long time. I wondered if you’d gone away to college.’

‘No. I’m fourteen.’

People often think I’m older because I’m tall for my age. I have Dad to thank for that. Mrs G is short – shorter than me.

‘I’ve been ill – I am ill. It’s ME – Chronic Fatigue Syndrome,’ I tell her. ‘I get exhausted after I do anything.’

‘How awful for you,’ she says.

‘This is the first time I’ve been outside for months,’ I tell her.

‘Goodness, is it really? You poor girl! So, what can I do for you?’

‘I’ve just come to bring you this.’ I hold out the parcel. ‘The postman left it with us. I’m sorry, I can’t stand for very long and I’ll have to get back now.’

‘Thank you, dear,’ she says. ‘It’s nice to see you. And if you ever fancy a change of scene – or company – you are welcome to pop in. And I mean that.’

I nod and smile. I always thought she liked keeping herself to herself. She doesn’t seem to have many visitors. But there’s a look of longing in her eyes as she says, ‘I mean that’ and I think she is genuinely lonely.

‘Everything OK?’ asks Mum as I come back into the house. She’s standing by the door and she gives a big sigh of relief. She’s clearly been waiting for me, worrying. I made it. I went next door to deliver a parcel and came back again.

‘Don’t make a big deal of it, Mum,’ I beg.

‘It’s progress, Kasia – progress,’ Mum says softly.

I nod. I am mega pleased with myself, though I’d never admit it to Mum.

Back upstairs I rest in bed for a while and then go and sit by the window. A few people are walking along the pavement, each in their own separate world, though they are only metres apart. A man on his mobile, a woman with smart high-heeled boots, a teenage girl with a bobble hat. A silver car appears and slows down near the girl. There’s something weirdly familiar about the scene, and my heart skips a beat as I remember the abduction. Is this the same car I saw? Is it going to happen again – to this girl? I am frozen to the spot.

The car pulls over, parks and a man gets out. He glances towards the girl. I hold my breath. She’s still walking, she hasn’t noticed the car. Fear rises in my throat – but the man is walking the other way. He’s heading for the barber’s on the corner. He goes inside.

I look again at the silver car and realise it isn’t the same kind. It’s a three door and a completely different shape.

My eyes turn towards the upstairs window at the house opposite. The curtains are closed and there’s no one there – but then I see one curtain move. A hand – a face – dark eyes, looking out. Then nothing. Again, I didn’t see clearly, but I’m sure it’s the same face I glimpsed before and I’m even more certain now that it wasn’t the face of the woman who lives there. This face is narrower, younger. A girl. Who is she? She disappeared so quickly.

The couple have a baby, but I’ve never seen a girl come in or out of that house. If she’s the one who was looking out of the window, then why did the woman lie about anyone else living there?