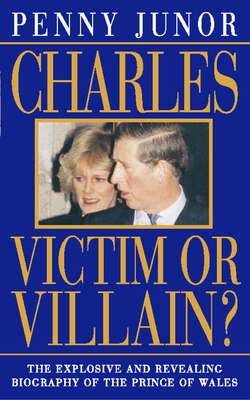

Читать книгу Charles: Victim or villain? - Penny Junor - Страница 13

The Discovery of Diana

Оглавление‘She was a sort of wonderful English schoolgirl who was game for anything.’

Friend of Prince Charles

When Charles first met Diana she was a nondescript schoolgirl of sixteen – his girlfriend’s little sister. He was in the midst of a lengthy and enjoyable relationship with Sarah, and they met at Althorp, where he had been invited to a shoot. Diana was nothing more than a slightly plump, noisy teenager, but he made a profound impression on this particular teenager and Diana secretly set her heart on him then and there and determined that she would become Princess of Wales.

Sarah’s romance with Charles came to an end when she spoke candidly to the press about it, saying, ‘I wouldn’t marry anyone I didn’t love, whether it was the dustman or the King of England. If he asked me I would turn him down.’ But they remained friends, and the Prince invited Sarah and Diana to his thirtieth birthday party at Buckingham Palace a year later, and a few months after that, in January 1979, they were both invited as guests of the Queen to a shooting weekend at Sandringham. That very weekend, their father, Earl Spencer, had come out of hospital following a brain haemorrhage that very nearly killed him.

Later that year Diana was staying with her sister, Jane Fellowes, in her house at Balmoral to help with Jane’s new baby, while the Royal Family was in residence at the castle. But the first time Charles saw her as anything more than a jolly and bouncy young girl whom he enjoyed taking out from time to time as one of a group to make up numbers was in July 1980, when they were both invited to a weekend party with mutual friends in Sussex. He had just had a dramatic and humiliating bust up with his latest passion, Anna Wallace, and he and Diana were sitting side by side on a hay bale while their hosts prepared a barbecue, when the conversation turned to Mountbatten, who had died the previous August. What Diana said touched the Prince deeply – as she knew it would.

‘You looked so sad when you walked up the aisle at Lord Mountbatten’s funeral,’ she said. ‘It was the most tragic thing I’ve ever seen. My heart bled for you when I watched. I thought, “It’s wrong, you’re lonely – you should be with somebody to look after you.”’

It is ironic that her sensitivity about Lord Mountbatten should have triggered Charles’s interest in Diana as a future bride, for Mountbatten would not have approved of the match. In losing his beloved great-uncle, his ‘Honorary Grandfather’, the Prince had lost his mentor; also, for a considerable time, he had lost his way in life. Mountbatten would have applauded Diana’s sweet nature, her youth, her beauty, her nobility and her virginity; but he would have seen that the pair had too little in common to sustain them through fifty years of marriage. He might also have spotted her acute vulnerability and the damage sustained by her painful start in life, and known that the Prince, with his own vulnerability and insecurity, was not the right man to cope with her needs.

Mountbatten’s murder had an unimaginable impact on the Prince’s life; it knocked him entirely off-balance. As he wrote in his journal on the evening he heard the news, ‘Life has to go on, I suppose, but this afternoon I must confess I wanted it to stop. I felt supremely useless and powerless …

‘I have lost someone infinitely special in my life; someone who showed enormous affection, who told me unpleasant things I didn’t particularly want to hear, who gave praise where it was due as well as criticism; someone to whom I knew I could confide anything and from whom I would receive the wisest of counsel and advice.’

Mountbatten had criticised the Prince of Wales, most notably for his selfishness, but he also made him feel he was loved and valued, which neither of his parents had ever been able to do. Where his father had cut the ground from under his feet, Mountbatten had built him up, listened to his doubts and his fears, rebuked him when he felt he had behaved badly, encouraged him, cajoled him, provided a sounding board for his wackier ideas, a shoulder to cry on, and given him some much needed confidence. There was no one else in his life at that time who could do this.

From the time when Charles was so touched by their exchange on the hay bale, to the announcement of their engagement, the romance was brief – less than seven months – and their moments alone were rare, but throughout the course of the relationship, Diana was in charge. She knew what she wanted and she went all out to get it. She had cherished her dream of marrying the Prince since their first meeting three years before, and with great cunning ensured her dream came true. She had always said since she was a small child that when she grew up she was going to be someone special. Her siblings called her ‘Duch’ – because she was determined to be a duchess at the very least. When the opportunity arose, she threw herself at the Prince, quite blatantly and brazenly. Yet it was only the more astute of Charles’s friends who realised what was going on. He didn’t appear to notice. Like most men he was easily flattered, particularly by a pretty young woman who professed great interest in everything he said and did, and manifested great sympathy and understanding for the trials and tribulations of his life. He found her quite intoxicating, and she was willing and amenable to do whatever might please him. She slotted neatly into whatever plans he already had, she talked about her love of the country and of shooting and her interest in taking up horse riding, and she liked his friends. And crucially, she made him laugh. She was fun.

But it was all a sham. Diana didn’t like any of these things. She hated the countryside, had no interest in shooting or horses, or dogs, and she didn’t even really like his friends. She found them old, boring and sycophantic. What she enjoyed was the city. She liked shopping in expensive Knightsbridge department stores, and lunching in smart London restaurants. She liked cinema and pop music.

Diana was a victim, who needed love and attention and constant reassurance – needs she carried to an exaggerated degree from her childhood. Her mother, Frances Shand Kydd, had run away from a violent and unhappy marriage when Diana was six years old and the experience of that loss – her feeling of rejection that followed when her mother disappeared – left deep scars in Diana’s psyche.

Frances Shand Kydd has been unfairly maligned for deserting her children, not least by Mohamed al Fayed when they attended an investigative meeting in Paris in June 1998 about the crash that killed both their children. He lashed out at her, saying, ‘She didn’t give a damn about her daughter … If you leave a child when she’s six years old how can you call yourself a good mother?’

Whatever her qualities as a mother, Frances had every expectation when she left home for good just before Christmas in 1967 that it would be a temporary separation. She intended to sue her husband for divorce on the grounds of cruelty, and it was unthinkable for a mother in these circumstances not to be given custody of young children. Her husband, Johnnie Althorp, who later became the eighth Earl Spencer on his father’s death, was a well-respected, genial, if rather dim, member of the aristocracy. He had been an equerry to George VI, then to Queen Elizabeth II.

Abuse ran in the Spencer family marriages and their thirteen years together had not been happy. To compound her misery, Frances had lost a child, a baby boy called John, born after Jane and Sarah, in January 1960, who only lived for ten hours. Diana was born eighteen months later, and then in May 1964 Frances gave birth to another boy, Charles, the son and heir her husband so badly wanted.

Shortly afterwards she met and fell in love with Peter Shand Kydd, a wealthy married businessman. Their affair broke up both marriages, and Frances seized the opportunity to escape. In the autumn of 1967 she and Johnnie had a trial separation, and at Christmas it became permanent and she left the family home. But her plans to sue for cruelty went badly awry. Shand Kydd’s wife, Janet, sued him for divorce on the grounds of his adultery with Frances. With that proven, Frances had no defence when Johnnie also sued for divorce because of their adultery. The cruelty suit was thrown out, and in the custody proceedings that followed, he brought some of the most influential people in the land to speak up for him – including her own mother, Ruth, Lady Fermoy, a considerable snob, who was said to have been appalled that her daughter had run off with a man ‘in trade’ – albeit a millionaire.

As a result, custody of Jane, Sarah, Diana and Charles was given to their father, who employed a string of itinerant nannies to take care of them. Frances was only allowed to have them on specified weekends and parts of the school holidays.

Diana said, ‘It was a very unhappy childhood … Always seeing my mother crying … I remember Mummy crying an awful lot and every Saturday when we went up for weekends, every Saturday night, standard procedure, she would start crying. On Saturday we would both see her crying. “What’s the matter, Mummy?” “Oh, I don’t want you to leave tomorrow.”’

One of Diana’s other early memories was hearing her younger brother Charles sobbing in his bed at the other end of the house from her room, crying for their mother. She understood none of what had gone on between her parents. All she could see, like any small child in a similar situation, was that her mother didn’t want her any more. She told Andrew Morton that she began to think she was a nuisance, and then worked out that because she was born after her dead brother, she must have been a huge disappointment to her parents. ‘Both were crazy to have a son and heir and there comes a third daughter. “What a bore, we’re going to have to try again.” I’ve recognised that now. I’ve been aware of it and now I recognise it and that’s fine. I accept it.’

Rightly or wrongly, Diana felt rejected, worthless and unwanted. Those were the feelings she nursed throughout her childhood and teenage years and, three weeks after her twentieth birthday, took with her into marriage. She was still desperately seeking love and reassurance.

Her mother’s departure was not the end of the trauma in Diana’s young life. In June 1975, shortly before her fourteenth birthday, her paternal grandfather died and her father inherited the title and the ancestral home, Althorp. It meant an upheaval from Norfolk, where she had friends and roots, to Northamptonshire, where she knew no one. Worse still, her father, whom the children had had more or less to themselves for the last eight years, had taken up with a formidable woman, Raine, Countess of Dartmouth, daughter of the romantic novelist, Barbara Cartland, mother of four and former member of Westminster City Council, the London County Council and the Greater London Council. To the children’s horror, the couple were married just over a year later, and the woman one of her friends described as ‘not a person but an experience’ took over Althorp and all who lived in it.

Diana’s education was poor. After prep school at Riddlesworth Hall in Norfolk, she followed her sisters to West Heath, another boarding school in Kent, where she passed no O-Levels, despite two attempts, and left in December 1977 at the age of sixteen. She went from there to finishing school in Switzerland but didn’t enjoy it; she came home after six weeks and refused to go back. She did some brief nannying jobs, learnt to drive, did a short cookery course, and briefly worked as a student teacher at Betti Vacani’s children’s dancing school in Knightsbridge. But that too she gave up. One day she simply didn’t arrive for work, and when she was telephoned and asked what the problem was, she said she had hurt her leg. The truth was that whenever the going got tough, Diana quit. After that she did cleaning jobs for her sister and any friends who wanted their flats vacuuming or their laundry done. She had been obsessively clean and tidy ever since she was a small child. At school she had done far more washing than anyone else. It was the one thing she was prepared to stick at.

On 1 July 1979, her eighteenth birthday, Diana came into money which had been left in trust for the Spencer children by her American great-grandmother, Frances Work, and was encouraged by her mother, as her sisters had been before her, to buy a flat with some of the money. The flat she bought was 60 Coleherne Court, said to have cost £50,000, which she shared initially with two friends. By the time she began seeing the Prince of Wales, she had three flatmates, Carolyn Pride, Virginia Pitman and Anne Bolton; and was working three afternoons a week as an assistant at the Young England Kindergarten in Pimlico, run by the sister of a schoolfriend of Jane.

Diana’s problem was that she had had no discipline in her life. Like so many children of divorced parents, she had been indulged. She was an extremely rich, extremely spoilt young woman, who was used to getting her own way. In marrying the Prince of Wales she was taking on one of the most disciplined ways of life in Britain.

The Prince of Wales was quite besotted by Diana at the time he asked her to marry him, and when she came to Balmoral in the late summer of 1980 everyone fell in love with her. She was a fresh, delightful, funny girl, with a podgy face and pudding basin haircut, who told jokes, had no clothes so borrowed everyone else’s, asked daft questions, knew nothing about anything, and made everyone helpless with laughter. Charles couldn’t believe his luck, that this lovely girl, whom all his friends seemed to find so attractive and engaging, said she loved him.

Charles’s excitement at finding Diana, who seemed to be perfect in every way, was quite touching. In public, the mask behind which he hides is impenetrable. In private, he has never been able to hide his emotions, and since he was a small child, if asked, he has always blurted out everything he is thinking and feeling. He has no guile, and over the years most of these thoughts and emotions have been committed to paper in letters and notes to friends and relations. As his feelings for Diana began to run away with him, his older and wiser friends told him that he should slow down and keep his cool, lest he blow it.

In August 1980, several of Charles’s friends were with him on board the royal yacht Britannia for Cowes Week on the Isle of Wight, the oldest yachting regatta in the world and one of the great events of the social season. He invited Diana, and confided to one of his friends that he had met the girl he intended to marry. Oliver Everett, an assistant private secretary, who had accompanied her to the yacht, returned to his colleagues in the office saying, ‘I think this is serious.’ In September the Prince invited her to Balmoral, again with his friends. By then he was confessing that he was not yet in love with her, but felt that because she was so lovable and warm-hearted, he very soon could be. The friends could see no objection. At nineteen she was younger than most of them by many years, but she was friendly and easy company and most of them warmed to her. She was fun and bubbly, and told Charles how completely at home she was in the country. As one of his friends said, ‘We went walking together, we got hot, we got tired, she fell into a bog, she got covered in mud, laughed her head off, got puce in the face, hair glued to her forehead because it was pouring with rain … She was a sort of wonderful English school-girl who was game for anything, naturally young but sweet and clearly determined and enthusiastic about him, very much wanted him.’

The Prince taught Diana to fish on the River Dee, and it was while she was out alone with him one afternoon that she was spotted by James Whitaker, at that time royal correspondent of the Daily Star, who had been pursuing Charles for many years to secure the scoop of the decade – the girl who would be Queen – and his tenacity can only be marvelled at. It was a matter of hours before Diana’s name, address and pedigree were all over Fleet Street and her flat in Coleherne Court in Chelsea was under siege by seldom fewer than thirty photographers. They followed her every move, telephoned her at all hours of the day and night, pointed long lenses at her bedroom window from the building opposite, and made her life totally intolerable until the engagement was announced five months later and she was able to move into the sanctuary of Buckingham Palace.

Charles was badly smitten, but his decision to ask Diana to marry him in February was not born out of spontaneity or conviction. It was a pitiful combination of poor communication, media manipulation and pressure that he no longer had the strength to resist. Diana was clearly suitable and in every way might have been tailor made. She came from a family that had been connected to the Royal Family for years, she understood the protocol, she was comfortable around them all. She was sexy, pretty and fun to be with. She was interested in all the things he was interested in, and young enough to fit in with his lifestyle without too much difficulty. The newspapers loved Diana, and the country wanted him to marry her.

It was still early days, but because the media had reached fever pitch – not entirely discouraged by Diana, who developed quite a warm relationship with people like James Whitaker during that time – Charles was forced into making a decision that he was not yet ready to make. Everyone wanted him to find a wife. The pressure from inside and outside the family was intense, and there were not many candidates by the 1980s who fitted the job description. Diana seemed as close to perfect as he had known. She appeared to love him very much, so, hoping for the best, the Prince allowed himself to be led by others.

There was one other decisive factor. It was one of the most inexplicable episodes, which has remained a mystery ever since and probably always will. In November, a story appeared in the Sunday Mirror entitled ‘Love in the Sidings’, which claimed that a blonde woman of Diana’s description had driven from London in the middle of the night, and been secreted on to the royal train for a few hours with the Prince while it was parked at a siding in Wiltshire. She had been telephoned and asked for a comment and said the story was quite untrue. Bob Edwards, the editor, was so convinced it was true that he published anyway, and was shocked by the unprecedented reaction from the Queen’s press secretary, Michael Shea. He demanded a retraction, calling the story ‘total fabrication’. Some years later, Edwards had a Christmas card from his friend Woodrow Wyatt which simply said, ‘It must have been Camilla.’ Camilla and the Prince both say the incident never happened – Camilla has never been on board the royal train – and neither they, nor any of the Prince’s staff who were around at the time have ever been able to get to the bottom of where the story could possibly have come from. The royal train is heavily guarded by British Transport police – it is their big moment – and when it stops overnight, there are patrols walking up and down both sides of the train, men on bridges, cars everywhere, plus a large crew on board. It is inconceivable that anyone could have been smuggled on to the train undetected, and if someone had seen a blonde woman smuggled into the Prince’s compartment, whether Camilla or not, the story would have been out long ago.

However, it was pivotal to Charles and Diana’s relationship, and it would not have been beyond the cunning of Diana to have tipped off the Sunday Mirror herself – nor some years later, consumed with jealousy for Camilla, suggested the blonde was Camilla.

The clear implication from the story was that Diana had slept with the Prince, which cast doubt on her virtue. The fact that the Queen should have been so quick to protect her virtue gave Diana a special status. She had not stepped in to protect any of the other women the Prince had been with. It further fuelled speculation that this one would become his bride.

Diana’s mother wrote to The Times appealing for an end to it all. ‘In recent weeks,’ she wrote, ‘many articles have been labelled “exclusive quotes”, when the plain truth is that my daughter has not spoken the words attributed to her. Fanciful speculation, if it is in good taste, is one thing, but this can be embarrassing. Lies are quite another matter, and by their very nature, hurtful and inexcusable … May I ask the editors of Fleet Street, whether, in the execution of their jobs, they consider it necessary or fair to harass my daughter daily from dawn until well after dusk? Is it fair to ask any human being, regardless of circumstances, to be treated in this way? The freedom of the press was granted by law, by public demand, for very good reasons. But when these privileges are abused, can the press command any respect, or expect to be shown any respect?’

Sixty MPs tabled a motion in the House of Commons ‘deploring the manner in which Lady Diana Spencer is treated by the media’ and ‘calling upon those responsible to have more concern for individual privacy’. Fleet Street editors met senior members of the Press Council to discuss the situation. It was the first time in its twenty-seven-year history that such an extraordinary meeting had been convened, but it did nothing to stop the harassment.

It was against this background that the Duke of Edinburgh wrote to his son saying that he must make up his mind about Diana. In all the media madness, it was not fair to keep the girl dangling on a string. She had been seen without a chaperone at Balmoral and her reputation was in danger of being tarnished. If he was going to marry her, he should get on and do it; if not, he must end it. The Prince of Wales read the letter as an ultimatum from his father to marry Diana.

Others to whom he has shown the letter believe that the Prince misinterpreted what his father wrote, and that to have laid the ultimate blame for his failed marriage on his bullying father is unfair. There was obviously an ambiguity that was never resolved verbally. The two men did not sit down and talk – indeed, they cannot sit down and talk, which is a great sadness to both.

The Prince was faced with an impossible choice. To ask Diana to marry him before he was quite sure she was the right girl, or to risk letting her go when she was so perfect in so many ways and things were looking so promising.

‘It all seems so ridiculous because I do very much want to do the right thing for this country and for my family – but I’m terrified sometimes of making a promise and then perhaps living to regret it.’

He allowed himself to be pushed into a marriage that he was uncertain in his own mind was a good idea. He confessed to one friend that he was in a ‘confused and anxious state of mind’. To another he said, ‘It is just a matter of taking an unusual plunge into some rather unknown circumstances that inevitably disturbs me but I expect it will be the right thing in the end.’

He knew he wasn’t in love with her, but he liked her very much, and he knew there was a good chance he would grow to love her. Mountbatten had told him to find a young girl and mould her to his way of life. Wasn’t someone like Diana precisely what he meant? More importantly, given the hysteria that Diana had caused in the media, what other girl would ever dare be seen with him, if this was the likely consequence? Convinced that his father was telling him to marry Diana, he decided to go with that decision and hope for the best.

Had Lord Mountbatten been alive Charles would have turned to him for help; and Mountbatten would in all probability have told him not to marry Diana. Yes, he had a duty to marry, but it was imperative for the Prince of Wales above all people, who could not contemplate divorce, to be quite certain he had found the right woman.

In Mountbatten’s absence, Charles consulted his official advisers, friends and family, most of whom were eager to approve. It is the curse of the Prince of Wales to be surrounded by friends and advisers, most of whom tell him what they think he wants to hear. Few have the courage to say what they think he needs to be told for fear that it might put an end to their friendship or employment. The Queen offered no opinion whatsoever. The Queen Mother, a hugely influential figure within the Royal Family to this day, was strongly in favour of the match. Lady Diana was, after all, the granddaughter of her good friend and lady-in-waiting, Ruth, Lady Fermoy. And Ruth, Lady Fermoy, who knew that Diana had emotional problems, which would make the match extremely unwise, failed to speak up.

Two of Charles’s close friends, Nicholas Soames and Penny Romsey, advised against marriage. Soames thought that the pair had too little in common, and saw an intellectual gap of giant proportions. Penny Romsey was similarly worried about the intellectual mismatch, but she was also very concerned that Diana was in love with the notion of being Princess of Wales without any real understanding of what it would involve. Penny told the Prince of her worries some weeks before the engagement, and persuaded her husband Norton, the Prince’s cousin, to do the same. Norton’s principal concern, like that of Nicholas Soames, was the intellectual gulf, which he predicted would lead to silent evenings, resentment and friction. All three were deeply suspicious about the way in which Diana had gone after the Prince so single-mindedly. They had seen how she controlled the relationship. She had wanted the Prince of Wales, she had flirted and flattered and been everything that he wanted, and she had got him. Romsey tackled the Prince on more than one occasion, becoming blunter with every attempt. The Prince didn’t want to hear, and he was angrily told to mind his own business.

Although he often seeks solitude, the Prince has a network of close friends upon whom he is very dependent and confides in, as they do in him. He is a tactile man; and he pours out love and affection to them, both male and female, although he has always tended to be closer to women. He speaks to them on the phone, writes long, soul-baring letters, and asks their opinion on every subject that interests or worries him. He confides far more than is probably wise, and is completely open and honest with them. In return they protect his trust absolutely. It is a tightly knit bunch, mostly older than him, and includes the Palmer-Tomkinsons, the van Cutsems, the Keswicks, the Paravicinis, the Wards, the Romseys, the Brabournes, the Devonshires, the Shelburnes and Nicholas Soames. They wield great influence with the Prince and are fiercely jealous of their friendship. Most of them have plenty of money, which is inherited, and not a great deal of sensitivity about how the other half lives. None of them shares the Prince’s enthusiasm for hunting but they indulge in all the other sporting activities of the British upper classes. They shoot grouse in either Yorkshire or Scotland, from 12 August through to December; shoot pheasant and partridge from October to February, and duck from a month earlier. They fish for salmon on any of the great rivers, mostly in Scotland or Iceland. They have large country houses, which the Prince visits, and in return they enjoy invitations to his family homes, to weekend shooting parties at Sandringham, and stalking and fishing holidays at Balmoral.

The Prince of Wales thought he had found the girl of his dreams, the girl whom the country would find acceptable, and who would be able to share his job and his life. He had not reached this judgement alone. He was not a normal man wanting a normal wife to live a normal life. He had waited a long time to find the right person, and he was now thirty-two years old. It was important for the country that he make the right decision, and he wanted to be reassured by his friends and advisers that he was correct in his selection. But though he canvassed opinion about Diana before he asked her to marry him, and he relied upon friends to bolster his resolve, once she had accepted his proposal, the subject was closed. He had made his decision, and was not receptive to advice, warning or criticism. He was determined that the decision to marry Diana was the right one, and when doubts began to creep into his mind during the five months before the wedding, he kept them to himself.

‘I do believe I am very lucky that someone as special as Diana seems to love me so much,’ he wrote to two of his friends. ‘I am already discovering how nice it is to have someone round to share things with … Other people’s happiness and enthusiasm at the whole thing is also a most “encouraging” element and it makes me so proud that so many people have such admiration and affection for Diana.’

The truth was rather different; but when his friends told him they had serious doubts about the suitability of the match, he refused to listen. When he himself began to have serious doubts about Diana, he refused to talk about it. He went ahead knowing that there was a question mark over the future. To have called off the wedding would have been horrendous and humiliating for everyone, and the headlines and public castigation could only be imagined, but with hindsight, it would have been infinitely less painful and less damaging to everyone concerned, particularly the monarchy, if he had had the courage to do it.

There are some close to the Prince who believe he had a duty at least to have discussed it. A relative goes so far as to say that his failure to do so was his big mistake.

‘In his position he bloody well should have spoken to people because he had to think of the constitutional side as well as the private side. He had chosen Diana with both sides in mind, but equally he needed to think of the consequences for both, if it was going to go wrong.’