Читать книгу Being Peta - Peta Margetts - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление

October began with Peta having an early morning trip to theatre so a port could be attached to a major blood vessel. This would make the frequent delivery of her chemotherapy much easier. The procedure was done under a general anaesthetic and, as a special three-for-one deal, she also had a bone marrow aspirate and a lumbar puncture. This was routinely done to make the delivery of the chemo more comfortable and to alleviate the chance of veins collapsing from such regular access. The ‘comfortable’ part was an interesting notion — having someone drive the equivalent of a four-inch needle into your body on a regular basis was far from comfortable. Peta’s port was located right on the bra line, just on the left breast, which was a plain nuisance much of the time. Every time she rolled over in bed the thing seemed to roll as well, which was a very strange sensation. Pete decided she was going to need some new pretty bras from then on. Who knew who was going to see them, and a girl needed to be presentable as well as comfortable.

Peta’s port was inserted without any problems, and she was safely returned to the third floor to recover. She came out of theatre with the port accessed and ready for her dose of chemo, but late in the day our doctor, Peter Downie, came up to chat with us. He had come in on his day off and explained that there was something extremely unusual between Peta’s twelfth and thirteenth chromosomes. This was the first time we had any inkling of Peta’s genetic uniqueness — she was B cell and only five percent of patients are B cell. The doctor thought we should go home and return the next Tuesday, as some more in-depth discussions needed to take place. The good news was that Peta was now in remission.

We were given the ‘okay’ to leave. The only trouble was that Peta had an insuflon in her stomach for administering chemo. No-one thought to remove the needle, so Peta endured a sharp sting in her stomach over four days. By the time we returned to the hospital, the spot had become very painful. Needless to say, Peta was happy to have it out. I was taught how to inject Peta through the insuflon. For the first two or three injections I didn’t know who was more afraid: me or her. I had never imagined that I would need to do this sort of thing — it was hardly in the mums’ manual. Peta insisted that I wear my glasses for this procedure, and rightly so, as the spot was miniscule. Peta’s new port proved right from the start to be extremely tricky to access and seemed to sit very deeply. Because ports are not firmly attached, they can move around until enough scar tissue builds up to help stabilise them. Even our very experienced day oncology nurses, who could almost access ports in their sleep, cursed the wretched thing for a while, but they mastered it soon enough. On one occasion, the port seemed to have flipped over. It wasn’t until Peta was out of it in theatre that two of our nurses, working in tandem, successfully accessed it.

In the days immediately after the initial diagnosis I had said that the best thing anyone could do for Peta would be to buy her a new bed. Peta’s bed was totally past its use-by date, and well and truly ready for the tip. Her friend Michael took that request to our school principal. The school community rallied around and quickly raised the funds.

Late one Saturday afternoon, Pete and I returned home to find her bed on the front porch. Soon after, Bronte and Claire and her brother, Ross, knocked on our door, ready to install a new queen-size bed, complete with all new linen, pillows, doona and, as an optional extra, waterproof lining (just in case). Ross, Claire and Bronte had encountered a day of disasters getting the bed to our door. There had been numerous problems and delays, capped off by a flat tyre in transit. While all this was happening Justine had taken Peta to the movies in order to get her out of the house. That had been followed by a stop for a killer brownie and a milkshake, and when that still hadn’t filled enough time, I took her shopping! What an effort it had been to keep this surprise from her. The bed meant that Peta would be comfortable after her chemo sessions. Given that she would be spending much more time in bed (a prospect she was quite happy with, in that typically teenage way), this was wonderful. Peta was delighted with her new bed — how she appreciated the gesture from everyone. There was enough room for her sisters to crawl in there with her. The new bed would become Peta’s best friend.

October proved to be an up and down month for Peta. She had been unwell pretty much all month, and each day seemed unpredictable. Peta had planned a special garden party for our birthdays (mine is the 18th, and Peta’s the 19th). Peta wanted them to be special, considering the year we’d had. She carefully made the invitations with her theme in mind. It was to be a girls-only event, with a carefully chosen menu, fine china and girly things. Peta wanted a nice, relaxing party where she could wear a particular dress that I had made for her. She was unwell for the whole week leading up to her seventeenth birthday and repeatedly said that she felt about seventy. I had a feeling that the party would not happen.

On 12 October, Madeline and her boyfriend, Kurt, moved to Queensland. They left for a change of lifestyle and a bit of adventure. Madeline had no doubt that her youngest sister would overcome her illness. She knew Peta was strong.

The following day, we went to Melbourne for a lumbar puncture and chemo as per usual. The day went to plan and we left in record time: in and out in an hour and a half! However, Peta was unwell on the way home, and she got progressively worse. All Ellie, Justine and I could do was maintain a clear path to the toilet and have a pile of chuck bags at the ready. The girls sucked up their own aversion to vomiting and bravely supported their sister, standing by with face cloths and removing those chuck bags. Finally, after many hours, the anti-nausea drugs kicked in and Pete got some sleep. Thankfully, the next day was better, but from then on the anti-nausea drugs were just as important as the chemo.

As our birthdays approached Peta was very pale and looked more and more like most of the other sixth-floor kids. She had become accustomed to her usually fresh face being blotchy and red — an unwelcome side effect of the chemo. Peta was less than happy about this, as she had always taken care of her skin. Her hands also peeled. Despite all of this, Peta was in very good spirits. All was going well at this stage, although life was no longer as predictable as it had been in the initial weeks of treatment. But she was in remission.

* * *

Friday 16 October 2009

We headed over to LRH because Peta needed blood and platelets. This was probably the first time Peta had any significant petechiae, which was the common indicator of the need for a blood transfusion. Just like all of the numbers we were so familiar with, those little dots became a part of the weekly routine. We had to stay longer than anticipated as Peta was neutropenic and our team at LRH were always very cautious with her. The blood products arrived late, as was now normal, and when I returned early on the Saturday morning Peta was unwell. She had spiked a fever while the blood was being administered. Whenever this happens, blood cultures need to be taken to see what sort of bug might be cooking. I suspected that we would be celebrating our birthdays in LRH.

I was right; Peta wasn’t going anywhere.

My good friend Gwen drove down from Melbourne to be with us for our birthdays and kept us company at LRH. Peta was very comfortable with Gwen, and her company was a nice diversion for us. At home, Ellie was cooking a special ginger cake for me. I managed to get a slice of it late that night, but I was only home for a nap then it was back to LRH the next morning for Peta’s birthday. I was hoping I could bring her home, but our hopes were dashed. Pete had to stay.

We made the best of a bad situation. Ellie and Justine, along with my parents, who had travelled down to see Peta, were instructed to come to the hospital instead. Naomi was rostered on in Emergency, so she popped in for a while before work. We all looked very silly, wearing masks that resembled duck beaks and trying to eat cake! Peta finally got to go home the next day, but even after all of the blood, platelets and antibiotics, Peta still did not feel well. She had to have a blood test, but despite having been pumped full of blood, our pathology girl could not get a drop out of her. It was off to RCH straight away.

Peta had more blood transfused the next morning, followed by her scheduled chemo. While she was in day oncology I noticed that Peta’s speech had slowed significantly. I asked Carla, one of the nurses, to listen to her. Carla got one of the doctors to check her out, but the doctor said she was fine.

Peta seemed to be alright for the rest of the day. We waited the required four hours after treatment, then headed over to our room at Ronald Mac House to rest up. Just before we left, another doctor performed a neurological check on Peta. He was satisfied with the results, so we left, knowing we would be back the next day for more blood and a long day of chemo.

Half an hour later we sat down to eat in the dining area at Ronald Mac House and Peta broke out in a red, hot, prickly rash all over her body. We ate quickly and returned to the Emergency department to have it checked out. It turned out Peta had reacted to the Asparaginase used in the day’s chemo — apparently this was not uncommon. This meant a different drug needed to be used. Peta was given a large dose of Phenergan, and she was very dopey when we finally crawled into bed around midnight. Ten minutes later, the fire alarm went off. I tried to wake Peta but she was comatose. I was amazed that she couldn’t hear it! I gave up trying to shake Peta into consciousness and ventured out with all of the other residents in various states of undress. We were relieved to find that it was a false alarm: someone had been smoking in the kitchen. I could safely return to my sleeping girl, who was completely unaware that anything was going on. The next morning, she did not believe that she had slept through the fire alarm.

The following day at the hospital, everything went smoothly. There was no funny speech or adverse effects from the chemo. We had to stay one more night, then we could head home.

* * *

The day after, we had a clinic appointment with Dr Peter Downie, who checked out all of the ‘funniness’, then we finally got the leave pass to go home. We stopped for Maccas at Cranbourne and I watched as Pete struggled to put the straw in the hole of the drink cup. I said maybe we should go back to the hospital, but Peta was uncharacteristically agitated and said, ‘NO!’ She wanted to go home. Although oddly grumpy, she said she was okay; she just had a headache. We didn’t talk much on the drive home.

We arrived around 4.30pm and Pete went straight to bed. A couple of hours later, Peta came into the kitchen wearing half of her cardigan. The left sleeve was flapping around — she could not get her arm into it. I got her dressed and brought her a small plate of fried rice. She sat there staring at the food and the plate as though she had no idea what to do with it. A few seconds later she had a hand either side of the plate and was trying to scoop the rice into her mouth with her tongue. I couldn’t believe what I was seeing. After a few seconds, I asked her what she was doing. Peta looked at me and could not answer. I knew something was very wrong. I looked carefully into Peta’ eyes and slowly asked her if she knew what she was doing. She answered with a very confused-sounding, ‘No?’

I called the ward at the Children’s and spoke to the nurse in charge. I explained what was happening and, after a brief minute while she digested the information, her response was clear: ‘Call an ambulance.’ It is not that simple where we live. Our doctors are in Foster but the ambulance won’t take us there — it would be Leongatha instead. We did not want that if we could help it, but we would take it if we had to.

We put Peta in the car and headed to Foster, with Justine sitting in the back with Peta so she could keep her eye on her sister. Just in case. If anything changed we would call an ambulance. If we could make it to Meeniyan, the ambulance would take us to Foster.

Peta was mumbling, but Justine succeeded in keeping her calm as we drove. We made it all the way to Foster, even managing to avoid a large wombat on the way. Larry was already there attending to another patient. He went to work, quickly assessing Peta, who by this stage was terribly distressed. She could not speak, she could not move her left side and she was visibly terrified. So were Justine and I. It was incredibly concerning to see Peta like this and we had no idea what had happened.

The attending nurse tried to access Peta’s port for IV antibiotics, but to no avail. We knew all too well how tricky it was. Thankfully, this nurse had a ‘one go’ policy, as she did not wish to cause any more distress than was necessary. Larry cannulated Peta’s arm instead, and all I could do was let her squeeze my hand as hard as she wanted. Her distress was made worse by the fact that she could not tell us anything. She had absolutely no idea what was happening to her and was very afraid.

I did my best to allay her fears while Justine followed Larry out of the room and he quietly confirmed what we had suspected — that Peta had suffered some sort of neurological episode. Larry had called for a chopper to take her to RCH. We had been home less than four hours.

The chopper wasn’t available, so an ambulance was coming from Wonthaggi instead. We waited for what felt like hours. I could see that Larry was worried; he kept scratching the stubble on his chin in the way that men do when things just aren’t right. Thankfully, by the time the ambulance arrived, Peta’s symptoms had begun to subside. I found it difficult to send her off in the ambulance alone, but I knew she would need her bag of stuff. I suspected we would be in Melbourne for at least a few days, so needed to pack. Peta was in very good hands with the ambos. It was now midnight.

Jud and I dashed back home. I threw some clean stuff in a bag and headed for Melbourne, leaving Jud with only two stressed dogs for comfort. I was relieved that it was a clear night and I didn’t have to struggle with fog as well as with my emotions. I arrived a few minutes behind the ambulance as the emergency staff settled Peta in the treatment room. The doctor came to assess what was going on. Peta got some sleep thanks to a combination of drugs and sheer exhaustion. I sat next to her all night. Our nurse kept me supplied with tea to keep me going. This was the most terrifying thing I had ever experienced and I dared not sleep. I knew none of Peta’s sisters would sleep either.

* * *

At 6.30am, I called Peta’s father in Queensland. He was shocked that such a thing could occur. Later that morning, Peta was moved to the neuro ward. Initially, Peta was in a shared ward with a perky girl of about thirteen who had been in hospital for many, many weeks. Peta enjoyed the chat, even if she wasn’t very good at engaging in conversation herself. Our doctor, John, was on call today and as much as he was concerned by what had happened, he was also fascinated. John said this side effect only occurred in about one percent of patients. He had no answers for us and it would be the neuro doctors who investigated what had happened and why.

During the day, Peta’s speech returned, although it was sometimes slow, and she had trouble remembering the words she needed. Her movement improved but her enormous headache remained. Scans were done, tests were done, and we saw many doctors. Peta was neutropenic and was transferred to her own room. She missed the company of her bright bedside companion.

Peta had said on a few occasions prior to this episode that she had a headache. It was only in the week after the stroke that I learned how severe these headaches had been — so bad she needed to go to bed and hold her head! Right from the early stages after diagnosis, we had been told not to take Panadol or other pain relief as it can mask other symptoms. Peta had adhered to these rules and just put up with the pain.

Peta had simply accepted that pain was part of her illness. She was told in no uncertain terms that she was not to endure this kind of pain. It wasn’t normal and it wasn’t typical of chemotherapy treatment.

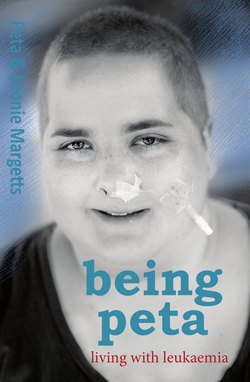

On Saturday, Justine did an amazing thing: she drove to RCH with Ellie. This was Jud’s very first venture driving to the big smoke. She even tackled the freeway! Pete was delighted to see her sisters, and they were relieved to see that Peta was still herself, still smiling and okay. Jud returned with Yome the following day. This was the day that Peta would finally farewell her hair. Up until now she had managed to hang on to her hair, even though she had long ago been promised it would go. Our room was quite a hot box, though, even at this time of year, and Peta was very hot and sweaty. The long strands of thinning hair were annoying her terribly. Yome, being the very prepared nurse that she was, had a pair of scissors in her bag. She and Jud were only too happy to trim what was left of the finery on top. There was a serious gathering of siblings in the bathroom and Peta’s makeover was complete. She looked pretty good with a stubbly head of hair. This hairstyle was so much better for Peta. She could now put her head on the pillow without the annoying shed of hair. Peta had only been bothered by the large balding patches in her hair, not the hair loss itself, which was never an issue for her.

On Saturday night, a tall, young, female doctor came and sat on the end of Peta’s bed. The doctor confirmed what we had already suspected: that Peta had suffered a recoverable stroke. The stroke had been on the left side of the brain. It was thought that the Methotrexate used in her chemo was the likely culprit, although it could have been any one of a number of drugs.

I slept on the bench next to Peta’s bed so I could watch her. I was constantly terrified. Peta’s speech would intermittently slow. Her face would contort and her fingers would twist. This continued until the Monday. Peta had one of the neuro doctors so fascinated he whipped out his mobile phone to video the contortions in her face. At least Peta knew when it was happening now and could laugh about how funny she sounded. She also enjoyed my cutting up her food, toddler style, and making choo choo sounds as I fed her. I stayed in Peta’s room for most of that week, even though there was a room available for me over the road. Things were too uncertain for me to sleep elsewhere. Later on in the week, I checked in to Ronald Mac House, but I stayed with my girl until ward closing time each night and was back again first thing in the morning, usually before she was awake.

It is fair to say that Peta could have gone just a little bit crazy in this room. I did my best to entertain her, and I spent my time parading from one side of the room to the other and lounging in the chair or on the long bench. Peta’s choices were far more limited: in bed, or out of it. The pigeons on the opposite window ledges were Peta’s amusement. She even did a painting depicting the two of us as pigeons — the conniving type. She saw them as opportunistic flying rats, always looking for a sly opportunity to attack. She would watch them and try to predict when they would make their move. She even gave them all names, like Sly Syd.

It was around this time that Micka, our Challenge support person in the hospital, first got a glimpse of the real Peta. There was some deliberation about what DVDs to watch over the weekend. Peta was quite the movie connoisseur, so it had to be a considered selection every time. Micka had brought Peta a list of titles so she could pick some movies to help ease the boredom over the weekend. He took up a position on the bench as Pete perused the thousands of titles on the list. After much — and I mean much — thought, Pete chose 27 Dresses, but it was the in-depth discussion about the merits of Mean Girls, and perhaps Peta’s comment ‘Suck on that!’, that gave Micka his first clue. ‘Did you just say, “Suck on that!”?’ Micka now knew Peta was not the shy flower he may have thought. Sorry, Micka.

Susie, the art therapist, provided plenty of art materials for Peta to entertain herself with. Other than that, there wasn’t much on offer, as Peta was limited by an IV pole and was very susceptible to infection. The good old iPod was the only thing that worked. Reading material had lost its appeal. Even Bleak House, which Peta had grown to love, just didn’t have any attraction, as Pete wasn’t able to retain any valuable quotes for her exams. The eighth floor was one very long straight line, so even going for a walk provided very little variation — just a long, slow walk, down one side of the corridor and back up the other side. Pete thought it would have been fantastic for trolley races, though.

* * *

Wednesday 28 October 2009

Just when Peta had pretty much gone crazy through sheer boredom, she had a lovely surprise. Her school vice principal, Jason Scott, brought her school friends to visit. Claire, Jane, Michael and Eli were a lovely diversion for her, and they came bearing lots of good wishes from classmates and teachers. It was the best thing for Peta. Jason delighted in telling us how proud he had been when some of Peta’s classmates had volunteered to donate blood after learning of Peta’s frequent transfusions. It was good for Peta’s friends to see what the hospital experience was like for her. For the first time, they were able to see what she endured as an inpatient.

One of the things Peta had been occupied with since her diagnosis was her Beaded Journey, a string provided by the Koala Foundation that is given to all of the kids after their diagnosis. Each string had the person’s name in blocks and a bead that signified the initial diagnosis, as well as beads for blood tests, lumbar punctures, chemo, bone marrow aspirates, special occasions, clinic visits — pretty much everything to do with the patient’s individual journey. Peta’s was full of cars, as her journey was one of constant travel, along with masses of blood tests, white chemo beads and red beads for all of her transfusions. It was growing rapidly and it showed her friends exactly how full-on this journey was.

After ten days on the ward, Peta was feeling much better. We were given a pass to go downstairs, where we had an hour in the hospital garden. This was heaven. We sat in the sun with our backs resting against the brick wall. Peta put her head on my shoulder and just let the sun do its best. The roses were out and it wasn’t too hot. For Peta, it was a special moment of freedom: no IV as a companion meant it was a chance to get around unaided and go unnoticed. One quiet hour of freedom. While in the garden we chatted to a fellow resident of Ronald Mac House with whom I had met. Her sixteen-year-old son had been revived after suffering a heart attack. Peta felt for this young man and wished them well. She had no concept of the seriousness of the event that she had just suffered herself.