Читать книгу SELF-STEERING UNDER SAIL - Peter Foerthmann - Страница 3

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Foreword

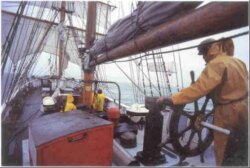

ОглавлениеThroughout human history people have been taking to the water in sailing boats, be it for trade, exploration or war. Not until our own century did the idea first surface that a sailing boat might be able to steer itself. In the heyday of the tall ships and even well into the modern era steering meant hands on the wheel. Crew were plentiful and cheap, and all the work on deck, in the rigging or with the anchor was performed manually. Where brute force was insufficient there were blocks and tackle, cargo runners and, for the anchor, the mechanical advantage of long bars and a capstan. Some of the last generation of tall ships, engaged in their losing battle with the expanding steamship fleet, did carry small steam-powered engines to assist the crew, but steering nevertheless remained a strictly manual task. There were three steering watches and the work was hard - even simply lashing the helm with a warp gave considerable relief. The great square-riggers plied the oceans without the help of electric motors or hydraulic systems.

In the early part of the twentieth century, recreational sailing was the preserve of the elite. Yachting was a sport for wealthy owners with large crews, and nobody would ever have thought of allowing the ‘prime’ position on board, the helm, to be automated.

It was only after the triumph of steam and the ensuing rapid increase in international trade and travel that the human helmsperson gradually became unnecessary; the first autopilot was invented in 1950.

Powerful electrohydraulic autopilots were soon part of the standard equipment on every new ship, and although the wheel was retained, it now came to be positioned to the side of the increasingly important automatic controls. Commercial ships and fishing boats quickly adapted electric or hydraulic systems to just about every task above and below deck, from loading gear, anchor capstans and cargo hatch controls to winches for net recovery and making fast. Before long ships had become complex systems of electric generators and consumers and as long as the main engine was running there was power in abundance.

Today, the world’s commercial and fishing fleets are steered exclusively by autopilots; a fact that should give every blue water sailor pause for thought. Even the most alert watchperson on the bridge of a container ship at 22 knots is powerless to prevent it from ploughing ahead a little while longer before gently turning to one side. A freighter on the horizon comes up quickly, particularly since the height of eye on a sailing yacht is virtually zero. Collisions at sea are not infrequent, and the sailing yacht seldom wins.

Modern freighters and ferries rely on autopilots even close to shore - Stena Line’s large ferries steam at full speed through the narrowest channels with only the Decca pulses of their purpose-designed software at the helm.