Читать книгу The Great Gould - Peter Goddard - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER ONE

ОглавлениеThe Enigma’s Variations

A little more practice is in order.

— Glenn Gould, New York, June 1955, while recording The Goldberg Variations

I often wonder about what people new to Glenn Gould, or those who only know his name, think when they come upon the life-size sculpture of the pianist outside the Canadian Broadcasting Centre in Toronto for the first time. Perhaps they wonder what exactly the artist is saying about him as they observe how the afternoon light on the folds of the surface make Gould’s clothing look as sleek as silk. This part of the city is about crowds and conventions and baseball fans and fun and chain restaurants. It’s not designed for thoughtfulness. Still, it’s possible. Me, I can imagine the unthinkable stretches of empty space beyond this point as I hear the trains heading east and west; once that was about all that brought anyone down to this part of town — the Canadian National and Canadian Pacific Railways. Those who know about such things know that the CN and CP were Canada’s first radio broadcasters and aired the first music show back in the days when the CBC was still on a drawing board.

I also think about the father of the jazz great Oscar Peterson, who was once a porter on one of those trains running out of Montreal. I remember also the Festival Express, the mobile Canadian Woodstock with car after car jammed with rock stars and wannabes heading out of town, one great collective raggedy-ass party, going west and even deeper into sixties mythology.

Equipped.

Timeless.

Gould and Peterson never played together, although both said they thought about it. But Gould knew about Janis Joplin, who was on the Festival Express. He included her song “Mercedes-Benz” alongside Bach and simple hymns in The Quiet in the Land, his 1977 radio documentary about Mennonite life.

I think of my father, stopping a bit west of here with me, so that I could get out of the car to see a bit of the city before I went on to my piano lesson at the Royal Conservatory of Music, then at the corner of College Street and University Avenue, since moved to Bloor Street.

Canadian sculptor Ruth Abernethy’s Glenn offers up a solid, handsome icon that reminds us that the slumped figure was taller in life than is often remembered. The work catches many signature Gould tics: he seems bent into the bench itself just as he melded with his piano stool; his right hand on his cap gives the impression it might fly off at any moment in a gust of Front Street wind; and his expression proclaims a stagey seriousness that might be, maybe, just a little over the top. “Hmm, yes, but, ah, speaking, as well one might, in Schoenbergian terms …”

You can practically hear a professorial Gould muttering on and on pedantically like this as visitor after visitor sits next to the master, deliciously aware that their rendezvous is a camera-ready setup.

Theatre is the key. It’s my theme, in a way. It was Gould’s theme, too. Media awareness: the star knowing where the camera was, where the microphone was. A familiar enough figure on Toronto streets back in the day, Gould could be found performing his own hobo lumpy young/old guy act, padded against the wind as if in a wintry battle scene in a vintage Soviet movie. Walking can be a subversive act, particularly if done with intent. And it certainly was for Gould, private and purposeful all at once. Where’s he going? What’s he thinking? might be questions people asked as he passed. What’s that he’s humming? This memory is now only the property of old-timers, and they’re unlikely to be walking those same streets as often — if they still exist at all, those streets.

Glenn Gould is always in motion in my lasting memories of him, although these images are always in black and white, like the National Film Board newsreels we were shown at school before any of our parents had a TV. Film rolling from the early fifties, when I might see him charging through the halls of the old Royal Conservatory of Music — “the Con,” as my father, a teacher there, called it. He was hugely famous just about everywhere in the world already, but not here, not really, as the rest of us struggled away with our iffy talents in cold practice rooms. I remember seeing him in the Con’s tiny cafeteria arguing away with someone, people coming up and talking to him. It’s still black and white in my memory from almost twenty years later, in the early 1970s, when I’d find myself crossing Glenn Gould’s path late in the afternoon around the old CBC building on Jarvis Street, where I worked for some years. In these memories, and in retelling them, I can’t simply say “Gould” — it’s too detached from the way one felt about him — but certainly not “Glenn” as in “Hey, Glenn.” It had to be Glenn Gould.

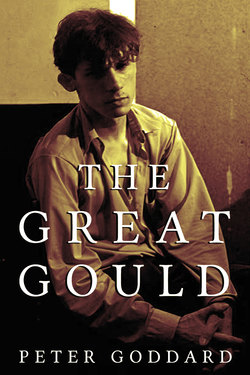

Not long after Glenn Gould’s death, Toronto artist Joanne Tod began a series of paintings dedicated to Gould, one showing the pianist looking grim-faced and hunched over the keyboard of a black grand piano — looking as long and menacing as a mob boss’s limousine (see dust jacket).

“I called my painting Idiot Savant,” says Tod. “It’s fixed within the context of the work I was doing at the time, which was to have ironic, double-meaning titles. His Goldberg Variations had been my introduction to the classical music genre — a classicism that sort of dove-tailed with my interest at the time in Manet — so there was some resonance there with him that I wanted to portray. But there were his eccentricities to account for, his ‘idiot-savantry,’ if you wish. I think he’s kind of hip, too. He’s wearing those long, pointed shoes. He has longish hair. If I’d known all about his bad habits I would have made him hot meals.”

We met a few times — he remembered I’d interviewed him on more than one occasion — and we’d stop on the street or in a hall and talk for a bit about what he was doing. One really late night at the CBC he appeared at the door of the second- or third-floor editing room I was using, startling me — “Like a ghost,” I told him.

I bet he liked that. The setting was right. The top-floor rooms in the old CBC building — offices, edit suites, storage, whatever else was there — had the murk and crannies found in attics in horror flicks. This added a little extra frisson for those lovers creeping upstairs for a late-night boff.

“And what are you working on?” he asked, moving close enough to peer over my shoulder. I don’t remember now — probably a segment of a breezy morning show, The Scene, he himself would contribute to.

I flattened a length of tape against the tiny metal block, cutting it at an angle with my razor blade, in the narrow slot provided. After another cut in different place on the tape, I brought the two pieces together.

“You realize, of course, that process will be taken over by a machine,” Gould said, straightening up.

“Probably,” I said. “But it won’t be as much fun.”

Tape splicing — replaced now by the digital edit suite, the MIDI (Musical Instrument Digital Interface) and other goodies — had its own set of quirky tools, including a marker of some sort to indicate where to splice a tape as well as a razor blade held in a special metal clamp to do the splicing, plus tape to piece the parts together. Veteran editors with eyes as sharp as diamond cleavers could fuse together two halves of the identical note recorded at different times with one of their fine tape splices. Gould’s editing prowess was a legend around the CBC. Indeed, as the years went on he seemed far more interested in extolling some frightfully complex bit of tape splicing he’d finished than his latest recording. A listener asked by Gould to guess the number of edits or splices in a finished documentary would inevitably guess far fewer splices than were there.

I now realize that Gould probably did little actual cutting on his own, especially after Columbia producer Andrew Kazdin’s revelations years later that he did the actual editing when recording with Gould, with Gould hovering around in an advisory capacity.

With me, though, Gould seemed stalled on the word fun.

“Less fun maybe,” he said, “but a logical step, a very human step, too — the step toward perfection — if you think of it.”

We talked a bit more and then he drifted away, leaving me to whiz strips of magnetic tape backward and forward, searching for the right spot to splice.

Reviving the Corps

The CBC’s English-language headquarters on Front Street is now home to the Glenn Gould Studio. The 340-seat theatre opened in 1993, eleven years after Gould’s death. It’s only one of several places around town with his name attached, most notably the Glenn Gould Professional School at the glassy new Royal Conservatory of Music. There’s also a Glenn Gould Park at the northwest corner of St. Clair Avenue and Avenue Road, with its statue of Peter Pan — entirely fitting for the boy-man Gould kept alive long after he was no longer a child. And I imagine the number of plaques bearing his name will increase with every new Gould connection that’s discovered by cities and towns he passed through for some project or another: Orillia, Wawa, North York …

All things associated with Gould have taken on a life of their own over the years, becoming almost totemic, fetish objects. Stories about his beloved Steinway CD 318 fill one book. How long before there’s a monograph on his familiar chair, bent like a Picasso sculpture? Somewhere stored away in one basement or another are the Gould family cottage shutters, much desired by Gould fans still looking for mementos.

The CBC statue, owned by the Glenn Gould Foundation, is different. It fixes this intensely private person forever in public. It places Gould in a different sort of space, a more public space where Gould is lesser known, if known at all — a place he himself would not have been ready for. Sculptor Abernethy’s roots in the theatre working with props and the like are apparent in Gould’s caught-in-motion pose. It’s almost as if he is impatiently waiting for a stranger to sit opposite him and talk. Ironically (the word irony hovers over everything Gould), his companions might be Toronto Blue Jays fans on their way to the nearby Rogers Centre, unaware of Gould’s dislike of competition. One can imagine the day when the majority of those strangers will be as much in the dark about Gould or what he did as are most tourists in Paris walking along Avenue du Général Leclerc unaware that its namesake was revered by generations of French as the liberator of Paris.

As with Abernethy’s sculpture, Gould, the idea, the subject, is always in motion, too. The Gould canon, a sizable enough collection while he was alive, has grown impressively in the years since his death in 1982. I’ve never heard anyone say, “Why, yes, I have a book on Glenn Gould.” It’s always, “I have several — well, quite a few actually.” But as Gould is discovered by a new generation of academics — the majority not around when he rocketed to world fame in the mid-1950s, and unencumbered by any personal contact with him — many are apt to see him in the broader context of popular culture. I’ve seen his name associated with the word hipster on occasion, and I get why, although I’m certain Gould himself would not. How else do you describe a brilliant recluse with shaggy hair who loved to drive big, shiny American cars out in the restless night, his pockets stuffed with uppers and downers, the radio picking up sad songs?

Those who are curious about Glenn Gould and dig deeper might be taken aback by just how many Gould narratives there are. The reason for this, of course, is his protean productivity on so many fronts: his recordings, wide-ranging in content and almost unrivalled in number; his intelligence and restless inquisitiveness, made public via his radio and TV appearances; his written essays and their rococo convolutions; and the logic-defying contradictions of his life. All of these aspects of Gould’s life have given rise to any number of narrative approaches. Hence, the themes-and-variations method for organizing any account of Gould, such as Otto Friedrich’s early biography, Glenn Gould: A Life and Variations, or Thirty Two Short Films About Glenn Gould, François Girard’s episodic film biography, or Georges Leroux’s Partita for Glenn Gould, whose introductory section, “Praeludium,” is followed by a “Toccata” then an “Allemande” and so on in musical fashion.

Ever the control freak, throughout his life Gould allowed the public, friends, and even lovers only glimpses of the private Gould. Over the years he left rooms full of scribbled sheets behind — notes, lists, one revision after another revision, the good revealed here, the bad there, but almost never anything one could consider reflective, overall. On July 30, 1952, when Gould was filling out his biographical data sheet at the CBC, he left answers to many of the questions blank. After What is your favourite amusement? Blank. After What was the most dramatic moment of your career? Blank. Under what circumstances do you like to prepare your program? Blank. What attracted you to radio? Blank. Blank for first audition. Blank for current programs. Blank for current sport. Blank. Blank. Blank.

Goulds Galore

Many believe the Gould enigma is one code that is not likely to be cracked — a view encouraged by Gould himself. It accounts for the paucity of intimate personal detail in his voluminous notes about, say, his love life, for just one instance. Peter F. Ostwald, the German-born American violinist/psychiatrist who counselled Gould as a friend over the years, called this the “diffusion of Gould’s identity” in Glenn Gould: The Ecstasy and Tragedy of Genius, a startling portrait of the artist in rapid decline. In the womb-like atmosphere of the radio studio, Ostwald says, Gould went through “a certain loss of the primary image of himself as a pianist, an image that had been built up in childhood under his mother’s guidance.”

The narrative of Gould that’s best known focuses on his career highs and lows: the discovery of a brilliant pianist whose 1955 recording of Bach’s The Goldberg Variations may well be the greatest classical recording of all time; then, watching as the freaky artist walks away from a multi-million-dollar career. And, well … that’s it. Well, not entirely. This particular narrative is enriched by circumstances surrounding his 1981 Goldberg recording, its autumnal atmosphere seemingly foreshadowing his death a year later.

The second narrative, Glenn Gould as one of the twentieth century’s great pianists, is of concern to a distressingly diminishing number of classical music cognoscenti. While generally impressed by the volume and scope of Gould’s recording activities, they remain unimpressed by what they feel is the inconsistency of its quality. They will point to senior elite pianists, from Vladimir Ashkenazy to Anton Kuerti, who insist that many of Gould’s performances are flat out wrongheaded. Several composers of works performed by Gould — the Czech-Canadian Oskar Morawetz, for example — have asserted the same thing: that Gould ignored basic musical signage to swerve off-road and do his own thing. Then there are the bootlegs of live concerts, and rumours about tapes of private recordings.

Story three: call it “Glenn Gould: YouTube Star.” Watching Gould live, still exhilarating, leaves still more unanswered questions. The narrative of Gould’s brief, incendiary, fretful, problematic, erratic, and eventually discontinued concert career — I mean the story of the concerts themselves before and after his dramatic early visit to the Soviet Union — may well constitute the greatest Glenn Gould unknown of them all, one that transcended his growing awareness of discomfort — psychological, physical, and aesthetic — with the process.

The fourth story (major film potential here) concerns the private, sexual Glenn Gould. This topic has seemingly lost its intrigue, having been exposed to some degree by Michael Clarkson, a journalist (and one-time Toronto Star colleague of mine) who established that Cornelia Foss, even while married to composer Lukas Foss, remained Gould’s mistress until his idiosyncrasies drove her back to her composer husband. Gould’s earlier historians tended to turn a blind eye to Gould’s sex life — well, some of them peeped, but only a little — even though Gould didn’t avoid discussing sex in his writing and thinking and yearning for Petula Clark and Barbra Streisand. That Gould might be gay has gained even less traction, although throughout his life he liked to have a guy pal, a buddy, close at his side, whether it was Ray Roberts, his hired factotum or Lorne Tulk, whom Gould considered a brother. As with some other artists — Goya, Mozart, Miles Davis, Dylan — turbulence in Gould’s private life seems to have energized his imagination. It was against the background of the disintegration of his life with Cornelia and her two children that Gould was at his most productive and, in public, his most upbeat.

Moody blue.

Story five explores Gould and Peter Pan, or more so Gould as Peter Pan. Gould didn’t cling to his childhood as much as it clung to him. He lived with his parents in their city home into his thirties, and he would repeatedly over the years retreat to the family cottage and memories from his childhood. He was close with his cousin, Jessie Greig, seven years older, who lived with the Goulds in Toronto while she went to teacher’s college. But the chilling of his friendship with Robert Fulford, his next door neighbour as a kid, left something missing in his later life, although that happened when they were both older, as Fulford points out, and were living radically different lives: Fulford by then was married with children, Gould an international music superstar.

Then there are the animals in his life. The first major news stories about him show him surrounded by his menagerie of pets. His last letter is about his abiding love of animals. One of his legacies is his gift to the Humane Society in Toronto. And the most beautifully lunatic moment — one I love him for more than any other — is when he tried to get a pack of watchful pachyderms to sing in German at the Toronto Zoo in 1978, in a scene appearing in the documentary film Glenn Gould’s Toronto.

Anyone writing about Gould needs to understand that whatever direction he or she takes, it is likely to lead to Gould having been there first. Once you’ve rounded this or that corner in some narrative, have solved this or that puzzle — or not — you’ll likely find he’s been there to elucidate in his words what you have just discovered. But not always. Because sometimes Gould buried the truth, unconsciously or deliberately, or somewhere in between; Gould’s archived scribbles and notes fill entire rooms in Ottawa, but the majority of their contents are clues, not revelations.

This particular Gould, the unfathomable artist, has a particular following. “He is our ideal of the disembodied artist, the pure intellect,” writes Kevin Wood in the liner notes of an early 1990s compilation recording called Glenn Gould’s Greatest Hits: Highlights from the Glenn Gould Collection, produced and marketed by one Kevin Wood. And yes, it’s true: elusiveness is a distinguishing characteristic of many historical classical geniuses. Wood points to Franz Liszt as an earlier example (although I’d hardly describe anyone selling his fans vials of his bath water for them to sip at rapturously, as Liszt did, as “elusive”): “The enigma of Gould is different; for him, there is no historical memory, no mystical tradition.”

Gould knew early on there was something very, very specific about him, something he’d later understand had historical antecedents. Glenn Gould’s many epiphanies — the music of Fartein Valen, the Norwegian Christian mystic, for example — started early on with understanding his own genius. The word genius seems inopportune now, best worked around or avoided because of its overuse in describing middling talents. Gould himself used the word, but almost exclusively to describe others. Yet there it was, this unfathomable talent. And he knew it.

He hated to be described as a prodigy. Gould rejected that designation his entire life. He knew about prodigies, of course. He grew up hearing about and performing Mozart as musical wunderkind. The first concert he was taken to by his parents — he was just six years old — was by Polish-born pianist Josef Hofmann. Hofmann had been acclaimed as a child prodigy, having given his first concert when he was only five.

There was something slick and superficial in the very idea of the prodigy. In an era of kid wonders, perky little simpletons showing off on amateur-hour shows on radio, Glenn was winning kudos playing serious music at serious music festivals. He had raw potential — at least he’d heard his mother brag about this raw potential. She also spoke of his unbelievably retentive memory, about his sense of perfect pitch that allowed him to sing a precise note without hearing it first. So, early on he knew he was part of a serious undertaking. He believed and trusted in his mother when she said he was on his way to something big, but all in due time. But due time was rapid-paced for both of them. The pages in the beginner music books young Glenn Gould was given, typical of the sort all children are given when they’re starting out, are remarkably pristine, as if each page needed to be open for just the shortest time.

With Mozart — the budgie.

Soon enough, Glenn Gould came across the craziest understanding about himself — or rather, about his abilities. Every school everywhere felt it had its own musical genius in its midst. It was the same with every community, every small rural town. And in each and every instance, the belief was that their kid genius was the one and only.

But Glenn Gould knew it was true only of him. He was that kid.

But I am also interested in another sort of epiphany and in a different narrative of Glenn Gould, which, in my estimation, embraces all others: his role in the creation of Glenn Gould, media star, media manipulator, and Canadian intellectual icon.

Not entirely unnoticed by earlier biographers, this instinct of Gould’s has been downplayed for reasons I understand. The motivation for Gould’s media reinvention of himself had been in place since childhood — he had dreams of being a broadcaster well before he achieved international acclaim as a quirky concert star — and this dream shaped many of his crucial decisions. The attention he attracted — and he both wanted and needed it — by way of his piano playing connected him directly to the burgeoning new world of innovative technologies, bringing the wired city together far more so than roads ever did. Gould became the singular source of a singular signal to be found on LPs, or FM radio, or hi-fi.

The piano, for all its polyphonic potential, in his thinking, was nevertheless designed for acoustic spaces, spaces increasingly unused or unwanted — front parlours once meant for entertaining, saloons, silent movie houses, and, yes, concert halls. In these orphaned spaces, he saw that pianos were becoming another form of furniture, needing polishing as much as tuning. But not yet for Glenn Gould. Not quite yet. For him, the piano was an extension of himself, like an artificial organ connecting past practices with the new. He played the piano and played through the piano to reach his true objective — the transference of sound into impulse and back into sound again.

All this complication of oxygen tubes, heating equipment; these speaking tubes that form this “intercom” running between the members of the crew. This mask through which I breathe. I am attached to the plane by a rubber tube as indispensable as an umbilical cord. Organs have been added to my being, and they seem to intervene between me and my heart.

— Flight to Arras, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry

Media Is the Message

Gould as the consummate media performer/subject/manipulator has not gone unrecognized, but has been downplayed. Gould “The TV Star” is a chapter heading in one book; “Vaudevillian” is the title in another. Lorne Tulk, one of Gould’s friends and technicians over the years, thinks Gould was fascinated by singer Petula Clark due to her ability to market herself. A number of Gould critics, and not a few admirers, have remarked on how adeptly he handled stardom.

“Can you think of another pianist who had such strong contact with contemporary media, who was so able to use them, to control them, and to make them serve his own ends?” asked French journalist and musicologist Jacques Drillon. “In the twentieth century, the artist without media is nothing.” Drillon was depressed at the thought. He might well have been encouraged.

Van Cliburn, Sviatoslav Richter, and Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli were Gould’s pianist rivals for a time, a type of rivalry that he disparaged in public and but never lost sight of. Before last-minute replacement of the suddenly vexatious Michelangeli for a CBC recording session of Beethoven’s Emperor Concerto, Gould reportedly said, “Just think that the Number One pianist is substituting for the Number Two.”

Seen from outside the somewhat conservative world of classical music, Gould might be said to have more in common with postmodernist writers or visual artists, where art’s production had yielded to interest in art’s reproduction (Robert Rauschenberg’s migration from assemblages to silk screens; Gould’s from live performance to entire reconstructions via editing). John Rea, a leading Montreal composer and teacher of composition at McGill University, points out that less than a decade after the 1955 release of The Goldberg Variations, there appeared an early Warhol silkscreen, Thirty Are Better Than One, consisting of a grid of multiple images of the Mona Lisa, most likely a comment on the grid of multiple Gould images on the famous Goldberg album cover, with Gould talking about the music but not shown performing.

Gould fashioned a beloved media figure out of his manufactured multiple personas. In this regard he rivalled Marshall McLuhan’s love of performing and media-readiness. For many artists the media was the new performance space.

John Cage, who once appeared on prime time American TV as a benevolent Zen dreamer, had funny ideas about what music was. Cage’s and Gould’s paths crossed on occasion, and Cage’s ideas were never entirely off Gould’s radar. For Cage, an idea could be performed, not only notes or sound. His forty-minute Lecture on Nothing contains the famous line: “I have nothing to say and I am saying it and that is poetry as I need it.” Based on the notion that art can never be possessed, it would have rattled the possessive Gould. (Elsewhere, Cage says: “Slowly, as the talk goes on, we are getting nowhere and that is a pleasure.”) Gould didn’t always get Cage, but nevertheless he wanted the American composer as part of the lineup for his Arnold Schoenberg documentary. In a letter he wrote to Cage to ask him to contribute to the project, Gould acknowledged that he knew Cage’s feelings about Schoenberg were “perhaps rather ambivalent.” In fact, Schoenberg and Cage operated on different musical planets, which Gould well knew.

However, Gould and Cage held in common a deep-rooted understanding of music’s potential to be the soundtrack for political upheaval and radical change. Cage’s 4’33” is three movements of silence — or rather, four minutes and thirty-three seconds during which a pianist doesn’t play a single note, leaving the audience to listen to its own sound: its own music, as it were. Cage’s “dismantling of the hierarchy between musical sound in particular and sound in general” was “arguably the single most decisive influence on our current preoccupation with the sonic environment as a suppressed but vital aspect of the social world,” observed American art critic Ina Blom in her 2010 ArtForum review of The Anarchy of Silence: John Cage and Experimental Art at the Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona in 2009. Gould, by turning his back on what he called the “penitentiary sentence” of being a touring concert artist, offered a radical alternative to the entire classical music apparatus and its insistence on the hierarchical superiority of the live concert. Gould, like Cage, understood the enormous power in silence; Gould just meant his own. (One is also reminded that musical “revolutions” have an extra-musical framework. Beethoven, arguably the first indie classical artist, understood that musical independence meant following the money, more easily found with the burgeoning mobile middle classes than with the politically vulnerable aristocracy.)

Back to the statue for a minute. Each Gould narrative is located where it should be. Abernethy’s statue places Gould’s media being at the CBC, which was home to him — another home. He had a desk at the CBC Radio offices. He sent letters on CBC letterhead, correspondence to fans from Bloomington to Auckland or to Madame Pablo Casals. As a return address he gave CBC Radio’s, 354 Jarvis Street. He kidded with the chatty ladies in the basement cafeteria: they were more likely the reason he was there than the food itself. Some nights when he was working on something, he could be found pacing up and down the CBC corridors, his very own version of Batman, coat flapping. A story I heard during my days there was how Gould, on a whim, intended to fill in for a newsreader when the one on the schedule was late turning up. He understood — he felt — his CBC audience, a crowd already familiar with his lightly mocking tone, his role-playing, his quirks and prejudices and love of words. There’s an intimacy there.

As well, the statue remains resolutely in the present tense through the varied, unpredictable, yet inevitably joyful interactions people have with it, a contrast with the image of him in his final years, with everyone hearing more and more reports of his poor health, torn soul, wrecked body, nighthawk hours, unfulfilled loves, and sunken dreams.

The last time I was passing by the CBC — when music was on my mind and not the Jays’ relief pitching (the building’s nearness to Toronto’s baseball stadium notwithstanding) — what I found myself thinking about wasn’t any of Gould’s iconic recordings — the Brahms Intermezzi, say — but his late-sixties recording of Liszt’s transcription of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony. This playing could’ve made the rock ’n’ roll charts because it’s soaked in show business swagger and sweat, starting with the motor-rhythmic drive worthy of Oscar Peterson riffing at full throttle right from the signature Da da da — DUM opening. (“You are too dumb,” Beethoven is supposed to have said when asked about the meaning of the opening.) And something more: the Beethoven is another crazily brilliant choice on Gould’s part, a retro choice given that playing transcriptions died out when the arrival of recording gave everyone the chance to hear the real thing. Cheeky, this.

Chilly Gonzales sure understands. The energetic jazz pianist shows his love for Gould in a YouTube tribute for Gould’s birthday. This passion, as Gonzales points out, is a love of caricature and parody, “the superficial aspect” of Gould, who “paved the way” for other generations of eccentric piano geniuses. Gonzales is talking about Gonzales, of course, he of the Gould-like emerging paunch and receding hairline. But he’s also channelling Gould’s own practice of self-parody. In Gould’s liner notes for his recording of the Fifth — written by a Gould seemingly connecting with his inner tweedy Brit music critic — he writes: “Mr. Gould has been absent from British platforms these past few years and if this new CBS release is indicative of his current musical predilections perhaps it is just as well.”

Gonzales’s Gould riff is not isolated either. Young deejays are remixing Gould tracks. YouTube surfers are blown away listening to the relentless, heartbreaking attack of Gould’s strafing technique. Gould’s name pops up in rock star interviews from the likes of Neil Young and producer Bob Ezrin and Patti Smith. The latter claims “a deep, abstract relationship with him. You can feel his mind.”

Discovering Gould is an ongoing adventure on the internet. I came across a posted vignette that sounds so much like Gould. The story came from a piece that appeared originally in the September 1998 issue of Hemispheres, United Airlines’ in-flight magazine. It’s by an American writer, Barbara Abercrombie, and she describes the last months of her mother’s life. When she went into the hospital, Abercrombie says, “I bought her a CD player and she listened to Glenn Gould’s Beethoven piano sonatas over and over. But she wasn’t just listening; she was working — figuring out how to improve her own playing. ‘I play this part too fast,’ she said. ‘Oh, listen to how he does it.’”