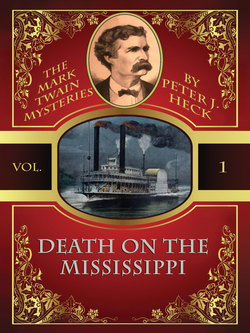

Читать книгу Death on the Mississippi: The Mark Twain Mysteries #1 - Peter J. Heck - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

6

ОглавлениеThe next morning was Sunday, and I woke to the sound of rain. My watch read 8:20. I put my head under the pillow and dozed a while longer, then roused myself enough to bathe, shave, and dress. A glance out the curtained window revealed a steady drizzle. Hearing no sound through the adjoining door to Mr. Clemens’s room, I wandered down to the dining room and breakfasted on coffee and sweet rolls, then (mindful of a promise made to my mother) headed for the hotel desk to determine if there was a church within walking distance.

“I beg your pardon, young man,” came an unfamiliar voice at my elbow. I turned to see the tall, gray-haired gentleman I had noticed on the train from New York and again at Mr. Clemens’s lecture the previous evening. He gave a little bow and said, “Please forgive the intrusion, but I believe you are traveling with Mr. Mark Twain?” His voice was deep and resonant, in keeping with his exemplary posture and slightly old-fashioned dress, vaguely military in its cut.

“Why, yes,” I said, “I am his secretary. And to whom do I have the honor. . . ?”

“Major Roy Demayne, formerly of the Twenty-fifth New Jersey, sir.” He gave another little bow. “It is I who will have the honor, in that I am to be one of the passengers on the literary Mississippi river cruise which Mr. Twain will be conducting.”

“Ah, I am not surprised. I saw you on the train, and then again at Mr. Clemens’s lecture last night. How can I be of service?”

“Well,” he said, spreading his hands. “I don’t mean to impose, especially on someone as busy as Mr. Twain—and I’m sure his secretary is no less busy. But I myself am an author, a poet to be precise, and I need the advice of an experienced literary man. As I am sure you know all too well, even an intimate familiarity with the muse does not guarantee one’s ability to navigate safely through the pitfalls of publication. But I understand that Mr. Twain, in consequence of his stature as one of the foremost literary lights of the age, is familiar with all the publishers on both sides of the Atlantic.”

“That may well be,” I said. “But I’m afraid I’ve been with Mr. Clemens—Mr. Twain—only a short while, and I am not yet completely familiar with his affairs. I am sure that he is well acquainted with the leading publishers, but I don’t know how I can help you.”

“Well,” he said again, with the same gesture. “I’m not sure this is within your purview, but I believe that a tête à tête with your employer might be of the utmost value in opening doors at the publishers. I have with me samples of my work, including selections from my heroic epic on several sanguinary engagements of the late war, in which it was my honor to lead men into battle in the service of the Union.”

“Indeed, sir,” I said, my interest piqued. “Which battles were you in?” I had always half regretted being born in peaceful times, when society showered its rewards upon the cautious and the reliable rather than the brave and adventuresome. The ritual combats of the football field were but tame substitutes for what men of the previous generation had seen at first hand.

“Well,” said Major Demayne, rubbing his lower lip, “we fought the Secesh all up and down the country, from First Bull Run to the Peninsular campaign. We weren’t always in the thick of it, but we were always mighty close to it. Some good men didn’t come home to tell about it.”

He shook his head pensively. “I have taken it upon myself to erect some small memorial in verse to their great patriotic sacrifice. I thought that perhaps Mr. Twain could spare the time to offer some words of advice to a fellow author.”

“Perhaps he could, although I really don’t know whether he has any interest in verse.”

“Why, surely he does; he has even included original verse in some of his novels. But perhaps it would be presumptuous for an amateur such as myself to impose on a man of his accomplishment. His free time is undoubtedly precious. That is why I approached you, Mr. . . . your pardon, I don’t believe I caught the name.”

I laughed and introduced myself, and we shook hands. “I’m afraid I can’t make promises for Mr. Clemens’s free time today or tomorrow; we’ll be traveling to St. Paul to board the steamboat. I assume you’re on the same timetable, since you’re traveling downriver with us. But perhaps once we’re on the boat, and things have settled down, he’ll have time to talk with you. I suspect there’ll be more than one aspiring writer with us—I’m planning to become a travel writer myself.”

Major Demayne’s face lit up like a freshly ignited gas lamp. “Ah, a fellow supplicant to the muse! You know, Mr. Cabot, I have often felt that prose is but a shoddy medium for the depiction of the marvels one sees in traveling. Give me Lord Byron, or someone equally inspired, for mountains or the sea! These modern fellows could learn something about turning a verse from him, or from Sir Walter Scott, you know.”

“Yes, I suppose they could,” I said. Not entirely certain I could recite a single line of either Byron or Scott, I was in no position to say much more; but the Major paid me no heed and continued with a full head of enthusiasm.

“I call to mind a passage in my canto on the great Battle of Antietam—which the rebs called Sharpsburg, after the town—that shows what a well-conceived metaphor can do for an ordinary scene. If you can spare a moment, I believe I have it with me.” He reached into his breast pocket and extracted a thick sheaf of papers, which he tucked under his arm while he fished in the opposite pocket for a pair of spectacles. Then he propped the glasses on the end of his nose and began leafing through his papers.

I had my mouth open to plead other engagements—true enough, if I intended to make my appearance in church this morning—when he glanced over my shoulder and folded his manuscript. “Well, perhaps this isn’t the time or place for a reading. But remind me to show you my verses when we are aboard the Horace Greeley, Mr. Cabot—and perhaps then I can impose on you to introduce me to Mr. Twain. A pleasure making your acquaintance.” He gave one of his little bows, turned on his heel, and walked quickly away.

Before I had time for any thought other than general puzzlement, a familiar voice came from behind me. “Well, Mr. Cabot, how are we this morning? Any sign of Mr. Twain?”

I turned to see Detective Berrigan, who, from the look of him, had just come in from the rain.

“I haven’t seen him yet,” I replied. “You seem to have been up and about early this morning.”

“Aye, that I have. I walked up to the cathedral on Superior Street for early mass—a bit farther than I’d wanted to travel in this weather, but that’s neither here nor there. On the way back, though, I came past the Windsor Hotel and decided to step out of the rain a moment, and incidentally to ask a few questions of the clerk and the bellboy.”

“And did you discover anything of interest?”

Berrigan smiled. “Now, would I be telling you all about it if I hadn’t? But rather than recount my story twice, why don’t we see if Mr. Twain is up and about, especially since it concerns his dear old friends from the river.”

* * *

Mr. Clemens answered our knock, dressed in another of his white suits. “Hello, Cabot—and Berrigan. What the blazes are you two up to this early? Have you both been to church?”

“Yes, and another place, too,” said Berrigan, saving me from admitting to my employer that I had neglected that duty.

“Well, you’d better come in and tell me the story, whatever it is. There can’t be too many other places of interest open on a Sunday morning, at least in this part of town.”

After hanging his damp raincoat and derby hat in the hall closet, Detective Berrigan settled into an armchair opposite Mr. Clemens and lit up his pipe. “I took the opportunity, returning from mass this morning, to drop by the Windsor Hotel. You may recall that’s where McPhee said he and his boys are staying.”

“Yes, he made a point of mentioning it. Do you mean to tell me they aren’t there?” Mr. Clemens leaned forward in his chair.

“Oh, they’re there all right—I spotted the back of McPhee’s head through the dining room door, so there’s no disputing that. But the interesting thing is that they didn’t all arrive together. First two of them came and reserved a room, and then the next day, the other two joined them.”

“Other two?” Mr. Clemens and I said it almost together. He looked at me and laughed, then looked at Berrigan. “Slippery Ed, and a pair of Throckmortons, and who else?”

“Well, I shouldn’t get too far ahead of myself,” said the detective, fiddling with his pipe. “The bellboy is the only one who’s seen all four of them; the desk clerk only saw the first two. And he said they were a big fellow and a little one, sort of rough-looking, whom I think we can identify—they checked in before dinnertime on Friday, just as McPhee claimed, and carried their own bags, which were pretty shabby-looking, the boy said, annoyed as he was to miss the tip. Then about noon yesterday, the bellboy saw the Throckmortons come in again, with an older fellow with long hair and a big hat—that’s got to be McPhee—and another man. McPhee and the other man both carried their own bags—they looked to be traveling very light, the boy said, one bag apiece. They went out again about an hour later.”

“Any idea who the other man was?”

“The boy described him as older than the Throckmortons, and heavy set, with a country accent and a big beard.”

“Damnation!” said Mr. Clemens. “You don’t suppose it’s Jack Hubbard. That would be almost too easy.”

“Well, I didn’t lay eyes on the rascal myself—McPhee was eating alone—not that it’d do me much good, never having seen this Hubbard fellow.”

“If he’s wearing his old disguise again, I’ll recognize him in a flash. I wonder if I can manage to get a peek at him.” Mr. Clemens stared out the window at the rain. “I can’t just sit in a corner of the lobby—they’d spot me ten miles off. There was a time when people didn’t know my face, but I’m sorry to admit that’s long past.”

“You’d never see hide nor hair of him, if he didn’t want you to,” the detective agreed. “Of course, it may be someone else entirely. But the interesting thing is that McPhee lied about his having been in the hotel on Friday night. Unless he can prove he was somewhere else in Chicago, his alibi won’t wash. And why would he lie to me unless he had something to hide?”

“Slippery Ed would lie just to pass the time of day,” said Mr. Clemens. “It’s a habit with him, like spitting or scratching himself. But you’re right about his alibi—it’s up in smoke. And if he’s with Jack Hubbard, he’s smack in the middle of your murder case. Damn it all, Berrigan, I don’t like this one bit.”

“Nor do I,” said Berrigan. “The best thing I can think of is to settle myself down in the lobby of the Windsor, to see if I can catch a glimpse of this fourth fellow before we leave for St. Paul. Then, at least, I may be able to give you a firsthand description once we’re on the train; if you think it’s Hubbard, I’ll see if the Chicago police will pick him up for questioning. And if I were you, I’d lay low until it’s time to board the train—just in case somebody gets funny ideas.”

Mr. Clemens gestured toward the window, where the rain continued to fall. “What choice do I have, with this weather? The only good likely to come of it is that it’ll keep McPhee from wandering around looking for mischief. That’s the single really admirable thing about him: he’s too lazy to go out in the rain, at least as long as there’s somebody to be swindled indoors—and there usually is.”

I never did get to church, and the rest of the day passed very much in the manner of a rainy Sunday anywhere. Mr. Clemens spent the afternoon lying in bed smoking, reading, and jotting down notes for his book. Before supper, I arranged for our luggage to be delivered to the station, and we had our meals sent up to his room. He grumbled a bit about being “shut in,” but went at his meal with a hearty enough appetite, and seemed content to be spending a comparatively uneventful day before getting down to the tour itself, when he would have to deliver a lecture almost every evening for several weeks—a schedule he admitted to me that he dreaded.

We took a cab to the Canal Street Union Station, where we boarded the Chicago, Milwaukee, and St. Paul overnight mail train at 8:00. After stowing our carpetbags in our sleepers, we retired to the smoking car to await Detective Berrigan’s report on his Windsor expedition. Mr. Clemens had barely begun to clip the end of a cigar when the detective entered the car.

“Well, how was the fishing?” said Mr. Clemens as Berrigan sat down across from us.

Berrigan frowned for a moment, scraping at the bowl of his pipe, then looked up and smiled. “Oho, my little visit to the Windsor, you mean. Well, for a while I thought it was going to be a wasted afternoon. When I arrived, I asked the clerk whether Mr. McPhee was in, and he allowed as how that party had gone out a short while before—hadn’t checked out, just left in a group. I figured they’d be back soon enough, with the weather and all, so I settled down where I’d have a good view of the lobby. Good thing I had your book along—it was six o’clock before they got back, and then only two of them.”

“Which two?” I asked.

“The Throckmortons, and I could tell as soon as they came in they were in a hurry. They went straight upstairs, and were back again in less than ten minutes, with the luggage. All the luggage—the bellboy told me that, after they’d left. He also told me they’d come in a cab, and had it wait while they went upstairs.”

“Listen to this story, Wentworth, and remember to tip all bellmen and porters,” Mr. Clemens said. “If McPhee had spent fifty cents two days ago, the fellow’s lips would’ve been sealed.”

“Well, I can’t say I disagree,” said Berrigan; having apparently scraped the pipe sufficiently, he pulled out his tobacco pouch. “Of course, the story I told him might’ve been an influence. Once I’d informed the young lad that the four tightwads were planning to waylay and rob Mr. Mark Twain, he was cooperation personified. He was the one that told me where they’d gone when they left, too—he heard them tell the hack driver to take them to the train station on Harrison Street—the Grand Central, just like New York’s. They were in a hurry, too.”

“Grand Central—some of the western trains leave from there,” I said, recalling my frantic study of Mr. Clemens’s lecture route before our departure.

“Good guess, son,” said Detective Berrigan. He paused a moment to light his pipe. “I got a cab no more than two minutes after them, and went straight to Grand Central. Sure enough, I was in time to see them board a train, along with Mr. McPhee—and someone else.”

“And what did he look like?” Mr. Clemens leaned forward, with an animated expression.

“Well, there’s the devil of it,” said Berrigan. “It was a woman they were with.”

“A woman!” There was a moment of stunned silence as Mr. Clemens tried to comprehend this revelation—I am certain I had no idea what to make of it. “Are you sure she was with them? What about the bearded man?”

“Well, Billy Throckmorton carried her bag, unless his taste in luggage is fancier than in clothes; and McPhee gave her a hand as she mounted the step. She was with ’em all right. And there was nobody else with ’em that I saw.”

“Damnation,” said Mr. Clemens. “You can paint me blue if this doesn’t blow all my ideas right up the chimney. I wish I’d been there to get a look at them!”

“Well, I don’t think you’ll have to worry about that,” said Berrigan. “That was the one other thing I learned. Our friends boarded the six twenty-eight Wisconsin Central, bound for Fond du Lac, Oshkosh, Chippewa Falls, and St. Paul—the same place we’re going. I think we’ll be seeing them again.”

We had sat absorbing this information for several moments when the car door opened and Major Demayne made his way down the aisle, nodding in our direction as he noticed us and hurrying along in the direction of the coaches. “Who was that old fellow?” said Berrigan. “I saw you talking with him this morning.”

“Oh, yes, I forgot him entirely,” I said. “His name is Major Demayne—he’s going to be one of the passengers on the riverboat. He told me he’s interested in poetry, and he’s written a poem about the Civil War. He’d seen me with Mr. Clemens, and he was asking about publishers.”

“The hell you say!” Mr. Clemens virtually exploded. “I should have known it. The wretched boat will be so full of literary amateurs it’s even money to sink before we’re out of Minnesota, with every blasted one of them hauling a trunkful of unpublishable manuscripts—novels without a plot, soporific sermons, and improving essays dense enough to make a bishop sick. And poetry! I’d rather be locked in a tiger cage than sit through another amateur poet reading me the ungrammatical nonsense that passes for poetry these days!

“Cabot, it’ll be worth your neck if that man reads me one single line of poetry. Keep him away from me—I’ll eat a skunk for breakfast before I listen to his stuff.”

“But sir—” I began to protest. The Major was, after all, one of the paying customers who made the lecture tour possible, and I figured he might even be talented.

Mr. Clemens shook his head vigorously. “No buts about it. I’ve got enough to worry about with Farmer Jack and Slippery Ed, let alone giving a lecture every night. If that fellow comes within ten feet of me with a piece of paper in his hand, I’ll pitch him overboard. And if you’re anywhere within sight, you’ll follow him directly, or my name isn’t Samuel L. Clemens.”