Читать книгу Up Against the Wall - Peter Laufer - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 4

ON GUARD

In 1993, the U.S. government imposed what it called Operation Gatekeeper along the border at San Diego. A high gash of concrete replaced ad hoc and sometimes minimal fencing while the Border Patrol bloated with new hires. But Operation Gatekeeper did not keep Mexicans out of the United States, it simply pushed them from the urban crossing point at Tijuana east to the rural deserts of California and Arizona. The Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) claimed it was not surprised that the migrants moved to the more dangerous deserts and continued to cross. “Our national strategy calls for shutting down the San Diego sector first, maintaining control there, then controlling the Tucson and South Texas corridors,” explained INS spokeswoman at the time, Virginia Kice. “We recognize that traffic will increase in other sectors, but we need to control the major corridors first.”1 It was a failed policy. Traffic across the borderline only grew, with deadly results (Figure 4.1).2

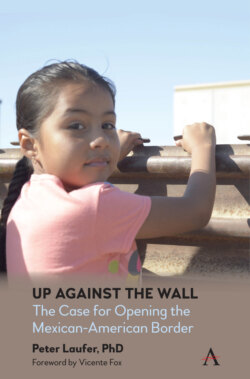

Figure 4.1 Marking division from sea to shining sea, the starkly differentiated Mexican-American borderline drops into the Pacific between San Diego and Tijuana.

In the first few years of Operation Gatekeeper, and the similar Operation Hold the Line at El Paso, the number of Mexicans who died en route north increased markedly. The University of Houston Center for Immigration Research, citing what it called conservative estimates, reported that well over a thousand undocumented immigrants died trying to cross the border from 1993 to 1996. “For every body found there is certainly one that isn’t,” said the center’s codirector, Nestor Rodriguez.3

“It’s a shocking number of deaths,” was the response from the late Roberto Martínez, then the director of the U.S.-Mexico Border Program for the American Friends Service Committee. “It sets us back on the human rights issue. It can’t be ignored by the governments on both sides of the border.”4 Yet in the years since, the border remained heavily fortified at San Diego and other urban centers and the death toll in the deserts keeps climbing. By 2020, the official body count was closing in on ten thousand, with the wilds of the desert undoubtedly providing the final resting place for scores more unclaimed and uncounted.

A report in 2001 by the U.S. General Accounting Office (GAO) had already condemned the Southwest Border Strategy, the name used by the Border Patrol for its scheme to dissuade illegal crossings by hardening urban ports of entry. By that time the Border Patrol had doubled its agent roster over a period of some seven years and had seen its annual budget multiply four times to well over $6 billion dollars. The result? “The primary discernable effect,” stated the GAO, was simply a “shifting of the illegal alien traffic.”5 And the deaths of over two thousand migrants.

The Southwest Border Strategy was the brainchild of former El Paso Representative Silvestre Reyes. Reyes held unique credentials for his job. He was the first member of Congress with working experience as a Border Patrolman. He retired after 26 years with the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 13 of them as Border Patrol chief in Texas. “The chaos of illegal immigration, uncontrolled and unaddressed, as it existed before I implemented Hold the Line in El Paso, was unacceptable,” Reyes testified. “It was unacceptable to the officers and it was unacceptable to the community.” Even as the deaths mounted in the deserts far from El Paso, Reyes expressed pride and confidence in the strategy.

I have first-hand knowledge of not only the difficulties and struggles we face on the border, but also of the success we have had with initiatives such as Operation Hold the Line and Operation Gatekeeper. While our Border Patrol has made progress, we all agree that we have a long way to go before we establish control of our 2,000-mile border with Mexico.6

The Border Patrol requires its agents speak enough Spanish to pass the agency’s language tests. That prerequisite is at least partially responsible for the fact that many of the agents are Latino. Some were born in Mexico and became U.S. citizens; some were born in the United States and have lived in Mexico. Others have parents or grandparents who came across the border without proper documents. Veteran agent Marco Ramirez was raised in Mexico, but says he does not let his heritage interfere with his work. “The way I see it,” he explains, “you carry the badge in one hand, and in the other hand, you carry your heart.”7

Immigration invaded presidential politics during the 1996 campaign, with both political parties inciting fear. First Bob Dole blanketed television with ads accusing Bill Clinton of being soft on undocumented immigrants. The pictures accompanying the aggressive narration were of migrants clandestinely crossing into California. Clinton was on the air in retaliation with pictures of a brown-skinned man handcuffed by the Border Patrol, inflammatory images that were punctuated by text claiming a 40 percent increase to the Border Patrol ranks during Clinton’s first term, along with record numbers of deportees.8

Shot Dead

More Border Patrolmen on the frontier, of course, resulted in increased encounters between them and Mexicans trying to cross into the United States. Over a weekend in late September 1998, Border Patrol agents twice reacted with guns to what they said were threats from Mexicans who were armed with rocks and refused orders to stop. Agents shot both migrants dead. The official Border Patrol explanation was terse, impersonal and clinical: “Fearing for his life, [the agent] brings out the weapon and shoots this person, striking the person in the torso area,” said Border Patrol spokeswoman Gloria Chavez about one of the shootings. Her colleague, Border Patrol spokesman Mario Villarreal said about the other, “The agent ordered him to drop the rock and stop. [The man] went on in an aggressive manner. The agent discharged his service firearm in self-defense, striking the individual in the torso.”9

“Something is going wrong,” was the response of the Mexican consul general in San Diego, Luis Herrera-Lasso, who explained that rock throwing is commonplace along the border and that the Border Patrol need not use deadly force to combat it.10

In 1989, the U.S. government sent regular army troops back to the Mexican border, this time with the rationale of fighting drug traffickers. On July 30, 1997, it suspended those border operations, two months after a Marine corporal shot and killed 18-year-old Esequiel Hernandez Jr. as the high school student was herding goats near his hometown of Redford, Texas.

Redford, understandably, was shocked.

“The only thing we know is that a good kid is dead who shouldn’t be,” said Hernandez’s English teacher Kevin Stahnke immediately after the killing.11

The teacher and the rest of Redford—the population in 1997 was 107—soon learned that Esequiel was herding his family’s goats down near the Rio Grande, as usual, the afternoon of the day he was killed. He was carrying his grandfather’s 1910 rifle, as usual, to protect the goats from a pack of wild dogs.12 He apparently shot a few rounds in the direction of brown shapes moving near his goats.

Those shapes were four Marines, covered in brush for camouflage, their faces blackened. They were deployed on the border for surveillance duty, assigned to track suspected drug smugglers and report on the traffickers’ whereabouts to the Border Patrol. These Marines were a unit of something called Joint Task Force Six, a Federal agency set-up to coordinate operations between the military and the Border Patrol. The U.S. military is proscribed by law from performing domestic police work. That prohibition was established in 1878 with the passage of the Posse Comitatus Act. But in 1981, federal law was changed to allow for cooperation between the military and civilian police, specifically for the purpose of stopping illegal drugs at the border.

Joint Task Force Six, known as JTF-6, was the work of then Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney, who—along with Joint Chiefs of Staff Chairman Colin Powell—chose to militarize the border, an escalation of the so-called War on Drugs. Part of their strategy was to deploy the Marines without telling local townspeople. Since Esequiel and the rest of Redford were not informed of the patrol, they also could not know the orders for the Marines’ tour in their neighborhood. Unlike domestic police, the Marines were not to identify themselves. They were not to fire warning shots. And if they felt threatened, they were expected to shoot to kill.13 These were their “rules of engagement.” As the months passed following young Esequiel’s death, that term, “rules of engagement,” infuriated the citizens of Redford.

“What are these ‘rules of engagement?’” questioned a neighbor of the Hernandez family, Diana Valenzuela. “We had no idea we were being engaged in the first place. I was amazed when I heard that the military was walking around the hills in our backyard.”

Another Redford schoolteacher, Leonel Ceniceros, agreed. “It seems crazy to me now that they were even here. When you think about it, these are young Marines brought in here from out of state. They’ve probably been told there are drug dealers all over the place, you’re in enemy territory, protect yourself. But the result is, this good young man is dead.”14

“They say they are trained to kill,” Esequiel Hernandez’s older brother said about the Marines. “They should kill in war, not in towns.”

The Marines essentially said the same thing in their initial official response to the killing. Marine Colonel Thomas Kelley told a news conference, “If you reach the point where you fire for fear of your lives, then you usually fire to kill.”

After Hernandez fired his grandfather’s old rifle, the Marines radioed to their Border Patrol associates that they were the targets of his shots. They tracked Hernandez and say he again raised his rifle and aimed at them. That’s when 22-year-old Corporal Clemente Bañuelos fired a single round from his M-16 and saw Hernandez fall. The Border Patrol recovered his body over twenty minutes later. The Marines did not try to save his life after he was shot; their orders did not require such follow-up. According to the autopsy, Hernandez bled to death.

“These people had no right to be here,” said retired Episcopal priest Melvin La Follete about the Marines. A friend of the Hernandez family, La Follete organized Redford citizens to fight against the militarization of their border town. “The Marines left their observation post, they stalked him, they came onto private property. And then they killed him. We were going blithely about our business, not knowing that Congress had handed away the civil rights of people on the border.”

Eventually the Hernandez family received $1.9 million dollars from the federal government in compensation for their loss of Esequiel. In return the government admitted no fault.

“This was a tragedy, not a criminal act,” said Jack Zimmermann, a lawyer for the shooter, Corporal Bañuelos. But the Texas Rangers were not convinced. After a review of the record, Ranger Sergeant David Duncan said, “The federal government came in and stifled the investigation. It’s really depressing.”

Esequiel Hernandez Jr. dreamed of a career in law enforcement. On his bedroom wall hung a U.S. Marine Corps recruiting poster.

Months before Hernandez was killed, the JTF-6 troops reported their first Mexican casualty. A Green Beret on duty east of Brownsville, Texas, took aim at a figure climbing out of the Rio Grande. Eleven shots later Cesario Vásquez, en route to Houston to look for a job, was dying.

Despite these tragedies, during the 2003 debate in Congress prior to the Iraq war, Colorado Congressman Tom Tancredo, a longtime proponent of militarizing the border, told his colleagues the United States was already fighting a home-front war. “Our borders are war zones,” he told them.15 “There is a war going on on our borders. People are being killed on our borders. Troops are needed on our borders. Our homeland needs to be defended.”

President Trump temporarily deployed the U.S. military to the border in 2018. Photo-ops included soldiers stringing razor wire along the existing barrier. Trump, with typical hyperbole, threatened a massive troop presence if Congress refused to spend the billions he was demanding for construction of his wall. “We will build a Human Wall if necessary,” he typed on Twitter.16

One of those Marines Trump sent to the Arizona border was Adam Woodward, who described his tour of borderlands duty as an exercise in boredom: just observing the desert, punctuated by rare police work. “One day we spotted these two individuals probably seven, eight miles out,” Woodward and his partner watched for an hour while “these guys are getting closer and closer.” The Border Patrol unit the Marines called had not arrived by the time the two hikers reached the Marine post. “They finally got up close enough where I could yell at them.” He ordered them to lie down. “They laid down where they were at.” The Marines and their detainees waited until the Border Patrol arrived to take over the case. And that was the climax of Woodward’s tedious role in Trump’s publicity campaign.17

Chaos Reigns

As Mexicans continued to die along the border from attacks by the U.S. military and the Border Patrol, at the hands of bandits and cheating coyotes, and from the extreme heat and cold of the desert, the United States continued its efforts at slowing the flow of migrants. In 1998, the Arizona border became the path into the United States with the greatest number of illegal crossings, according to the Border Patrol, outstripping Tijuana where the extensive patrols and the expanding wall convinced migrants that the Arizona desert was a better risk. The next year the Border Patrol caught nearly half a million undocumented migrants in Arizona, a doubling of their caseload in just five years.18 By the year 2000, the radical wall along the Tijuana-San Diego line was replicated in the Arizona desert at Douglas, across from Agua Prieta. But five miles of floodlights and cameras, sheet metal and iron were unable to do anything but complicate the crossing and make it more expensive and dangerous for illicit travelers, pushing them away from the urbanized Douglas–Agua Prieta twin cities and into the unforgiving wilds of the desert.

Agua Prieta presidente municipal Daniel Fierros could see from the changes in his city how futile the Southwest Border Strategy and its new strip of wall in the desert north of his town were to U.S. goals of securing the border. “People who didn’t have income rent [rooms in] their houses,” he said about the economic boom new migrants brought to his part of the border. “People sell fast food and things to cook with. Taxis get more business. And the coyotes do very well. We don’t condone it, but it’s a business as lucrative as drug trafficking, without the risks.”19 By 2000, hundreds of guest houses—just homes with rooms to rent—were operating in Agua Prieta, catering to border crossers waiting for the right moment to head north.20

In 1994, there were 58 Border Patrol agents working out of the Douglas station. By 2000, their ranks soared toward six hundred, by 2020 close to four thousand agents were on patrol just along the Arizona line. And still the trail north filled with migrants on the move.

The people-smuggling business thrived as the border became harder to cross. Coyotes upped the prices for a guided crossing; they fought with each other for the lucrative human cargo. Warfare between smuggling syndicates spread from Mexico and the border further north into U.S. cities. More expensive and sophisticated smugglers promised to get migrants far from the border into safe houses where they could rest and make onward plans before disappearing into American crowds. Again, the U.S. government responded with force, doubling the number of immigration agents in Phoenix, for example, to one hundred. “We’re dealing with ruthless individuals who view human life as nothing more than cargo for profit,” said Michael Garcia, acting assistant secretary for Immigration and Customs Enforcement.21 “Smuggling-related violence in the Phoenix area has reached epidemic proportions,” Garcia said about the need for more officers.

Phoenix police reported instances of rival traffickers kidnapping migrants from each other and holding them for ransom. Day laborer Anna Roblero said she was one of those kidnap victims when she arrived in Phoenix after paying a coyote four hundred dollars for passage across the border. “We walked for three days and three nights through the desert,” she told National Public Radio during an interview on a Phoenix street. “When we got across the desert, the smugglers told us to wait for some men to pick us up, but they never came. We didn’t know where we were.” Different smugglers then took custody of the group and demanded more money. Roblero said she called a cousin, who was able to raise the money, but it took over a week, a week she spent confined in a house. “I just cried and cried. I thought I was never going to see my kids again. They had guns and I thought they were going to kill us. Thank God my cousin came and gave them the money.”22

Since a conviction for people smuggling usually results in a much less severe jail sentence than a conviction for drug smuggling, experienced criminals from the drug trade saw a business opportunity with human cargo and moved into trafficking in human beings.