Читать книгу Reaper Force - Inside Britain's Drone Wars - Peter Lee M. - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

INTRODUCTION

Оглавление‘I DROPPED MY SON AT SCHOOL IN THE MORNING, CONTINUED ON TO WORK AND, WITHIN A COUPLE OF HOURS, KILLED TWO MEN. I WENT HOME LATER THAT DAY TO BE GREETED BY MY SON WITH A CHEERY, “HOW WAS YOUR DAY?” DO YOU LIE TO PROTECT HIM OR DO YOU TELL THE TRUTH?’

JAY, REAPER PILOT

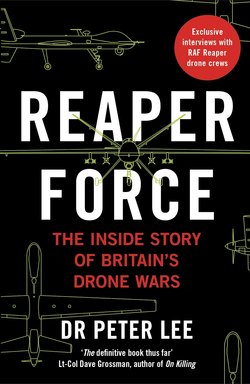

This is a book about the unknown community of the RAF Reaper Force. It is a group that embodies a series of contradictions: aircrew who never leave the ground, who are unseen but regularly in the news and who operate at the cutting edge of technology yet rely on the basic roles of air power – surveillance and attack – that have existed for more than a century.

The biggest contradictions, however, surround the aircraft they fly, remotely via satellite links, from distant continents: the MQ-9 Reaper. For many, perhaps most, people outside of the military, the Reaper is a drone. The word ‘drone’ implies that they are autonomous, self-thinking, emotionless robots but this overlooks the vast technical infrastructure and hundreds of people needed to operate the Reaper squadrons, and ignores the three crew members that fly each aircraft from a Ground Control Station (GCS): the pilot, SO and MIC. Furthermore, ‘drone’ becomes almost meaningless because it puts the Reaper in the same category as small hobby quadcopters. These hobby drones typically weigh less than 20lbs, measure 30–60 centimetres in diameter and typically stay airborne for less than an hour. They must be flown ‘line of sight’ (that is, you have to be able to see them with the naked eye), and fly no higher than 400 feet.

In contrast, the Reaper is a fully functioning aircraft with a 60-foot wing span that is piloted remotely from a GCS far away. It can carry four 100lb Hellfire missiles and two 500lb laser-guided bombs, operates at 20,000 feet, and can stay airborne for between 12 and 20 hours depending on its weapon load. To fly a Reaper the pilot has to pass aviation exams and (s)he must follow the aviation rules and laws that pilots of manned military aircraft must follow. Practically and legally, the International Civil Aviation Organisation recognises the Reaper as a remotely piloted aircraft (RPA). When combined with all the elements that make it work, like satellite communication, computer links, crew and infrastructure, it is formally known as a remotely piloted aircraft system (RPAS).3 Similarly, RAF personnel and RAF air power doctrine refer to Reaper, aircraft, RPA or RPAS. Therefore, for the sake of accuracy and authenticity, unless the context calls for the use of the term ‘drone’, such as my entry into the Reaper world in Chapter 1, the remainder of the book will also refer to Reaper, aircraft, RPA or RPAS as I take the reader inside what is more widely referred to as Britain’s drone wars.

What became known as the ‘drone wars’ started with the USA’s use of the MQ-1 Predator immediately after 9/11. By 2006 the Predator had been joined by the MQ-9 Reaper, which brought improved endurance, weapon load and sensing equipment to America’s ongoing War on Terror. The Predator and the Reaper would become mainstays of conventional USAF military operations and unconventional CIA operations. Amongst the best books to capture the technological and military developments in the US at that time is Chris Woods’s Sudden Justice: America’s Secret Drone Wars.

By the time the RAF acquired the Reaper from the US in 2007, a new vocabulary of war had already emerged. Outside the military, the term ‘drone’ was used almost everywhere to describe these RPA, while the crews who operated them were stereotyped as ‘Playstation killers’4: detached, disengaged, remote and emotionally disconnected from their targets. The chapters to follow will challenge these stereotypes and assumptions, as the extent of the visual, emotional and psychological immersion of the crews in the operations they conduct becomes apparent.

I had my first conversations with a few British Reaper pilots and SOs in late 2011 and 2012. I had been out of the RAF for several years by then and approached them with a negative attitude towards their work, which reflected the general tone of media comment at the time. But, once I got talking to them, I found an intense mental and emotional engagement with what they did and with the people they targeted. The quote at the start of this chapter was merely the starting point for deeper and more insightful conversations in subsequent years.

A major source of frustration for the British Reaper personnel has been, and still remains, that the actions of the RAF’s two Reaper squadrons have been conflated by the media and anti-drone lobby with the CIA’s use of the Reaper and the Predator. (I have spoken informally to several USAF Reaper and Predator pilots who did not like being linked with the actions of the CIA. Specifically, they did not want to be associated with the large numbers of civilian deaths attributed to the CIA.5) So, I found it difficult to reconcile the experiences of the RAF Reaper personnel that I was beginning to encounter with some of the more extreme claims that were being made about ‘drone’ operators. For example:

He is a drone ‘pilot’. He and his kind have redefined the words ‘coward’, ‘terrorist’ and ‘sociopath’. He is the new face of American warfare. He is a government trained and equipped serial killer. But unlike Ted Bundy or John Gacy, he does not have to worry about getting caught. It is his job… A CIA strike on a madrassa or religious school in 2006 killed up to 69 children, among 80 civilians.6

There was something akin to an obsession with zero CIVCAS (civilian casualties) among the British crews I spoke to and later observed in action. The attitude was influenced by RAF civilian casualties from an incident in 2011 (see Chapter 5). I was a King’s College London lecturer specialising in the ethics of war and air power in 2011 and 2012. At the time, the same weapon system – the Reaper – was reported as producing high numbers of civilian casualties by the CIA, while the RAF was reporting one incident. My academic background in the ethics of war, and years of lecturing on military air power, told me that the difference in casualty numbers had to come down to the contrasting policies of different governments and the Rules of Engagement (RoE) that they imposed on their respective Reaper Forces.

A scalpel in the hands of a skilled surgeon is used with precision and purpose, but still damages healthy tissue; a scalpel used without skill, or used by a torturer, can disfigure faces and bodies. The Reaper with its 100lb Hellfire missiles can be unbelievably accurate in, say, hitting a moving vehicle or a single individual. However, I do not want to draw too strong a comparison between the relative accuracy of a scalpel and a Hellfire missile. A ‘surgical’ missile strike can be very accurate compared to the use of a ‘dumb’, unguided bomb, but it is obviously not the same degree of precision as a surgeon achieves in a hospital. A small missile is still a missile: fire it into a dense crowd of civilians and many of them will be killed and wounded. A 500lb bomb will make a proportionately bigger explosion with the potential to kill more people, combatants or non-combatants.

The key question is this. How many civilian deaths will a government allow its armed forces to inflict in the pursuit of the government’s aims? Bluntly, the US considers itself to be at war and has been since 9/11, while the UK has chosen to participate in several military operations during that same period. These political differences have dictated the degree of force that successive US and UK governments have been willing to allow their Reaper Forces to use. Many individuals and organisations either do not know or understand these subtle differences, or they have ignored them for the purposes of the arguments they want to make. For example, the charity War on Want stated:

Drones are indiscriminate weapons of war that have been responsible for thousands of civilian deaths. Rather than expanding the UK’s arsenal, drones should be banned, just as landmines and cluster munitions were banned. Now is the time to stop the rise of drone warfare – before it is too late.7

This statement links ‘thousands of civilian deaths’ with the UK’s drones – the Reaper, in other words – despite evidence including the UN’s 2010 report on ‘extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions’ that does not even mention the UK or the RAF Reaper in its criticisms of drone use.

I have deliberately laboured these political and technical issues here because they provide the background to both my research and to the operations carried out by the RAF Reaper Force. They should also be borne in mind during the chapters to follow. From here on, however, my focus is on the pilots, SOs and MICs, past and present, who conduct the UK’s Reaper operations. They do not work in isolation, however, but are the most visible part of a vast and complex system. It takes an extensive array of people and skills, across several countries, to get a Reaper airborne and to enable it to function across continents: engineers of different types, communications specialists, computer programmers, operations support personnel, weapons technicians, armourers, intelligence gatherers, imagery analysts, air traffic controllers, aerospace battle managers, Joint Terminal Attack Controllers (JTACs), lawyers, logisticians, flying programme administrators and many more besides.

Crucial though, and often overlooked in conventional books about war or air power, are the spouses, partners, families and friends that send the Reaper crews off to war every day. They live with the pressures, the fatigue and the emotional overflow from the daily operations conducted by the crew members. Many also spend a large proportion of their time as, effectively, single parents. It is not possible to write about the members of the Reaper Force in isolation without showing how their work impinges on family life, and vice versa.

And now, the structure of the book, which seeks to immerse the reader in the lives of the Reaper operators, from the claustrophobic, fast-moving, life-and-death decisions in the GCS to the human cost, the moral dilemmas, and the triumphs and failures that they experience. There is no strict chronological sequence, as RAF Reaper operations in Afghanistan, Iraq and Syria are explored. Depending on who is speaking, and when, several names are used for the group who sought to establish a caliphate across Syria and Iraq: ‘ISIS’ (Islamic State of Iraq and Syria), ‘ISIL’ (Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant), ‘Daesh’ and ‘IS’ (the self-proclaimed Islamic State). I use ‘IS’ for its brevity, while remembering its apocalyptic ambition and vision and, as a United Nations Human Rights report stated, for ‘imposing their radical ideologies on the civilian population’.8 This radical ideology is enforced by extreme violence, enslavement, rape, murder, torture and more.

In the first three chapters, I take the reader into ‘Reaper world’ through my own experiences as I set out on my research. Chapter 1 follows the journey from Las Vegas to Creech Air Force Base and into 39 Squadron, concluding with the pre-flight briefing for the day’s mission. Chapters 2 and 3 are spent in the GCS with two different crews on successive days. The first day captures hour after hour of surveillance activities, while the second day sees two missile strikes against IS jihadists. Chapter 4 is the most historically focused of the book, providing an insight into the origins of the UK Reaper Force through the eyes and experiences of several pioneers who developed their understanding while serving on exchange with the USAF Predator fleet.

Chapters 5-9 are all highly detailed and operationally focused, highlighting specific individuals or experiences. Chapter 5 recounts the 2011 civilian casualty incident through the eyes of the MIC involved, going on to reflect on living with what happened that day. Chapter 6 challenges many assumptions about gender and war as ‘Tara’ flies Reaper operations, including her employment of lethal weapons, through to advanced pregnancy. Chapter 7 provides a major ‘What if?’ moment for a crew whose target fixation could potentially have had a disastrous outcome, then follows the retraining process that brings them back to full capability again. Chapter 8 re-lives the moral dilemmas of one Reaper SO who struggled with killing, and controlling missiles onto human targets. Then Chapter 9, Happy Boxing Day, proves to be anything but as a crew spends Christmas night 2014 helplessly observing a series of horrors on the ground in Iraq, whilst being unable to intervene to protect the ‘friendlies’ below.

The final four chapters are more reflective. Chapter 10 brings together the thoughts and experiences of a range of Reaper crew members in their own words. Chapter 11 provides a moment-by-moment account of one of the most famous RAF Reaper missile shots from those involved. The shot disrupted a public execution and the video was released by the MoD at the same time as it was announced that there would be no medallic recognition for the Reaper Force personnel for their fight against IS. The penultimate chapter gives voice to several spouses and partners who speak about their lives with those who go to war every day, and the challenges they face. The final chapter combines my own thoughts on what I have seen and experienced, with reflections from Reaper operators on the personal legacies of having been at war, continuously, for up to seven years and more. One additional, unplanned chapter appears as an Epilogue and captures a glimpse of the human cost of war. It started as a brief, personal account from a Reaper MIC who witnessed the death of a US Marine, Corporal Matthew Richard, in Afghanistan, and still remembers it every day. The story evolved over several months as I got to know Cpl Richard’s parents, his Squad Leader and five fellow squad members, who all shared their perspectives on what happened on 9 June 2011.

3 RPAS is the legally designated descriptor used by the International Civil Aviation Organisation. See http://www.icao.int/Meetings/anconf12/IPs/ANConf.12.IP.30.4.2.en.pdf, accessed 23 July 2018.

4 Cole, C., Dobbing, M. and Hailwood, A., Convenient Killing: Armed Drones and the ‘Playstation’ Mentality (Oxford: Fellowship of Reconciliation, 2010).

5 Philip Alston, 28 May 2010, Report of the Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions, Study on Targeted Killings, Human Rights Council, UN Doc. A/HRC/14/24/Add.6, http://www2.ohchr.org/english/bodies/hrcouncil/docs/14session/A.HRC.14.24.Add6.pdf, accessed 5 February 2018.

6 Vic Pittman, Salem News, 18 April 2013, ‘Cowardice Redefined, The New Face of American Serial Killers’, http://www.salem-news.com/articles/april182013/american-killers-vp.php, accessed 10 February 2018.

7 War on Want, ‘Killer Drones’, https://waronwant.org/killerdrones, accessed 10 February 2018.

8 Pinheiro, P.S., 18 March 2014. Statement by the Chair of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic. United Nations Human Rights, http://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=14397&Lang ID=E, accessed 12 February 2018.