Читать книгу Royal Transport - Peter Pigott - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCN003788

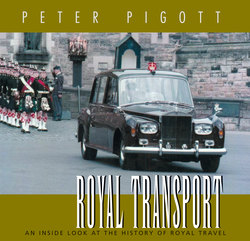

Buckingham palace on wheels — the Canadian National Railways carriages used by Their Majesties in the Royal Train in 1939.

On June 13, 1842, Her Majesty Queen Victoria took her first train ride. Precisely at noon, the Great Western Railway (GWR) steam locomotive Phlegethon departed Slough (at that time the station for Windsor Castle), pulling the royal saloon and six other carriages for Paddington. The stimulus for this trip had been her consort, Prince Albert, who had been riding in trains since 1839 and had finally been able to convince Her Majesty to try the newfangled, steam-hissing machines. Along with the rest of her household, Victoria dreaded the prospect, and it was only the trust in her beloved Albert that gave her the courage to attempt it.

The Phlegethon was a 2-2-2 locomotive and not yet a month old. Sharing the cab with the driver was the great engineer (and principal shareholder in the GWR) Isambard Kingdom Brunei and his Superintendent of Locomotives, Daniel Gooch. Built at the Swindon railway works, the royal saloon consisted of three compartments, with Her Majesty and her consort in the centre one. Brown in colour, the compartments were typical of the day: stagecoach-like boxes that were unheated and brakeless, with weak couplings, the passengers’ comfort and safety depending on an entanglement of chains to keep the train together. Her Majesty’s personal coachman rode on the footplate of the locomotive, as though behind horses. Repeatedly told that the engine had no need for his vigilance, he still insisted on pretending to handle the controls during the journey. Sadly, the smoke and soot so blackened the poor man’s magnificent scarlet coat that he never repeated the experience. When the train pulled into Paddington (then a small station, as the present building had not been built), the journey taking twenty-five minutes, Her Majesty pronounced herself charmed by the whole experience. A fortnight later, she returned to Windsor by train, bringing her infant Albert Edward (later the Prince of Wales) with her. Queen Victoria was not the first European monarch to ride in a British train — the King of Prussia had already enjoyed the comforts of the GWR, as had the Queen’s aunt, the dowager Queen Adelaide, consort of William IV.3

Her Majesty’s ride set the template for all royal train journeys to come, and many of the measures adopted during her reign have remained in use until recently. Even then, special precautions were taken to provide Her Majesty with privacy, comfort, safety, and security. Fearing that the event would attract crowds that might spill onto the tracks, the railway positioned employees on platforms, bridges, and in all towns en route until the royal train had passed. Other trains along adjoining tracks were halted and their contents examined. In later years, a pilot train would be sent ahead, and when there was more than one railway line, trains running parallel to the royal train were forbidden to match its speed, so that passengers could not look into Her Majesty’s saloon. As for speed, Queen Victoria forbade the royal train to travel faster than forty miles per hour during the day and thirty miles per hour at night. Later, her carriage would have its own semaphore signal: a small disc erected on the roof by which Her Majesty’s attendant could let a lookout man on the locomotive tender know that the Queen wished the train to slow down. Also, afraid that they might fall asleep on duty, Her Majesty periodically commanded that both the driver and fireman take sufficient rest periods, whether they wanted to or not. Finally, when the royal train went by, so as not to offend the royal eye by their attire, all railway employees, from station master, foreman, plate-layers, signalmen, gatemen, and shunters to guards and porters, were ordered to be dressed in their finest — even the firemen had to wear whites gloves while handling the coal. The Phlegethon set the trend for all royal locomotives in being lavishly decorated with flags and bunting. Taking it to the extreme, on later royal trips, the top layer of coal on the tender was painted white.

For travelling on the continent, Her Majesty personally owned a twin pair of six-wheeler saloons that were maintained at Calais. These were an exception to the rule, for unlike the other royal means of transportation, royal trains were never owned or maintained by the government (like the Royal Flight and the royal yacht) or by the royal household (like the carriages and cars). Except for those two saloons, neither the state nor the royal family ever purchased their own carriages or locomotives and, to this day, royal trains have been provided by railway companies, with the present royal train owned and managed by Railtrack.4 A total of twenty-two carriages were constructed during Victoria’s reign by the railway companies for her and her family, and while the cars were maintained for their exclusive use, they were never provided free, as the railways charged for their use.

It was with the acquisition of the rural residences — Osborne in 1845, Balmoral in 1852, and Sandringham in 1862 — that the royal family began to travel great distances out of London. For the honour of transporting them, the railway companies went to prodigious lengths, not only with the building of ornate and luxurious saloons but also elaborate stations at the royal residences of Sandringham (Wolferton), Osborne House (Whippingham), and Balmoral (Ballater). No railway station conveyed its royal origins better than Wolferton. Two miles from Sandringham House, the station’s origins date to the opening of the King’s Lynn-to-Hunstanton branch railway line in 1862, the year in which the Sandringham Estate was purchased by Queen Victoria for the young Prince of Wales. In 1863, the Prince of Wales and his bride, Princess Alexandra of Denmark (later Queen Alexandra), arrived by the royal train at Sandringham after their marriage and honeymoon. As the railway link between Sandringham and London, the station grew in importance, and its buildings were rebuilt in 1898 in Tudor style by W. N. Ashbee, the architect of the Great Eastern Railway buildings. Between 1884 and 1911, a total of 645 Royal Trains arrived at Wolferton, conveying Queen Victoria and many of the other crowned heads of Europe to Sandringham, including the German Emperor Wilhelm II and the future Russian Emperor Nicholas II. Politicians and statesmen also arrived on its platform to seek royal favour, and local railway employees never forgot the mad Russian monk Rasputin showing up to harangue the royal family — only to be sent packing back to London. As with the railway that built it. Wolferton Station was the scene of many great royal occasions. In 1925, the funeral procession of Queen Alexandra, who had come to Sandringham as a young bride, departed from the station on its way to London. From here too departed the royal train conveying the body of King George V to London for his state funeral in 1936, and in 1952 the funeral train of King George VI also began its journey at Wolferton. In later years the station was used regularly by the royal family, becoming associated in particular with the traditional Christmas and New Year holidays at Sandringham.5 The last time a royal train was used at Wolferton was in 1966, and the railway branch line closed in 1969.

British Railways Board

The GWR carriage built for Queen Victoria did not have a dining car or toilet, as Her Majesty would not use either while the train was in motion. It did have a signal on the roof to tell the engine driver to slow down.

One of the royal saloons built for the use of Queen Victoria in 1869 by the London and North Western Railway.

Having a member of the royal family use your company’s carriages bestowed honour far out of all proportion, and from the earliest days of train travel, royal trains always encompassed the very latest in rail technology, with each of the railway companies, whether in Britain. Australia, or Canada, vying to outdo their rivals. It was also a means for the railways to try out, on the most fastidious, most discriminating passengers, innovations like heating, toilets, and dining cars before introducing them to the general public. If the GWR built the first eight-wheeler coach for Queen Victoria in 1842, the following year the London and Birmingham Railway was the first to put heating into the saloon they hired out to the royal household. Ingeniously hidden between the plush ottomans, the Louis XIV chairs, and the Axminster carpet was a closed-circuit hot-water pipe heated by four oil burners. In 1851, the South Eastern Railway built the most conspicuous royal carriage to date. A six-wheeler, with the principal saloon twelve feet in length between two coupes, it was highly ornate, the walls padded in amber, white, and damask. At one end was a huge state chair, as the saloon was to be a travelling Throne Room. There was also for the first time a closet at one end that contained a lavatory, which, so as not to offend Victorian sensibilities, was cleverly disguised to look like anything but a toilet. Before that, if the Queen wanted to use such facilities, her train stopped at the nearest station — which meant that every station en route had to be prepared for a royal visit.

In 1861, the London and North Western Railway (LNWR) put the first full-length bed on a royal train, and eight years later the same company also built the first British railway coaches to be connected by a flexible concertina “bellows,” or gangway. It would be another two decades before these appeared on the trains that Victoria’s subjects used. But Her Majesty mistrusted these gangways and still insisted that the train be stopped whenever she wanted to walk from one carriage into the other. Similarly, Her Majesty refused to take her meals while the train was in motion. She felt the same about the use of gas and electricity for illumination, which in 1893 the LNWR fitted to her carriages, preferring instead oil lamps and candles. Her apprehension of electricity did not prevent her ringing the immense electric bells that were mounted in the compartments of her ladies-in-waiting to summon her staff. Finally, the Queen was also sensitive about what she viewed from the train. When passing through the slums of industrial Britain, not wanting to be affected by the suffering of her people, she had the blinds in her carriage lowered.

C-081691

Specially built observation car used by the Prince of Wales in 1860 for the opening of the Victoria Bridge, Montreal.

Queen Victoria’s best-known saloons were the twin six-wheelers built by the LNWR in 1869 to take her to Balmoral twice a year, and today one is preserved at the National Railway Museum, York. In 1897, now an old lady. Her Majesty was even more cautious: when the GWR wanted to honour her by building a replacement for her old saloon, she warned them: “Build a new train and as fine as you wish, but leave the private apartment in my carriage as it is. Through the skill of the Swindon craftsmen, her old salon was successfully incorporated into the very latest design. It had three different types of lighting — gas in the brake carriages, electricity in the remainder of the train — but only oil lighting in Her Majesty’s saloon.

Royal saloon built for the use of King Edward VII in 1902 by London and North Western Railway.

It was her son Edward VII who was truly the Railway King. Born in 1841, he had never known (as his mother had) a world before steam, and had no qualms of sleeping, dining, or doing anything else on a train. During his nine-year reign, he would travel by royal train constantly (and quickly, insisting that the speed be raised) in England. Scotland, Wales, and Ireland and on the continent. As he smoked cigars, his mother did not like him using her personal saloon. In any case, he would not have been seen in his mother’s old LNWR carriages — as a true gentleman. His Royal Highness preferred to be surrounded by furnishings of teak and leather, rather like a moving gentleman’s club. In 1897, Edward had his own royal train built for him by the London, Brighton & South Coast Railway (LBSC). His Royal Highness bestowed his patronage on this line because it connected a number of racecourses together, places that his mother frowned upon but which her son frequented. The Brighton Royal Train, as it was called, consisted of five eight-wheel bogie carriages: two saloons for the household, two for the luggage, and one for His Royal Highness — and sometimes Princess Alexandra.

The Prince of Wales was the first member of the royal family to use a train in Canada during his 1860 tour. The Canadian Pacific Railway, then barely begun on its transcontinental route, built a special carriage and an observation car for him. His Royal Highness travelled from Montreal to Toronto, opening public gardens, dancing at balls, planting trees, and chatting with specially selected “ordinary people.” He took to the tour with gusto.

Prince Edward’s brother, the almost unknown Prince Alfred, was less fortunate. The first member of the royal family to visit Australia, he arrived by battleship in 1867 and toured Adelaide, Melbourne, and Sydney, receiving everywhere a tumultuous welcome — except in Clontarf, Sydney, where on March 12, 1868, Irish patriot Henry James O’Farrell shot him. O’Farrell was arrested (before he could be lynched), convicted, and then hanged. The prince made a quick recovery and was able to leave Australia by early April, but the national disgrace persisted until the turn of the century, when the country was once more thought safe for Royal Tours.

When Edward became king in 1901, the LNWR retaliated against the LBSC’s Brighton train by designing its own grand creation. Costing an estimated $300,000, this train was constructed at its works in Wolverton, following the King’s suggestion that “it look as much like a yacht as possible,” and presented along with its own locomotive to His Majesty in December 1902, causing one American newspaper to comment that His Majesty had been given the ultimate boy’s Christmas gift of a complete train. This was untrue, as the train (like all royal trains) remained the property of the company, and the royal household was always charged first-class fare plus the rate per mile for a special train. Of the two suites on the LNWR train, the King’s had a smoking room, a day compartment, a bedroom with dressing room attached, and a saloon. Mahogany, inlaid with rosewood and satinwood, featured heavily in the smoking room; the leather chairs were comfortably upholstered, and the curtains, carpet, and general fittings harmonized in this dark colour scheme. In contrast, the adjoining compartment used by Her Majesty was in white enamel, decorated in the Colonial style, and the furniture was in satinwood, with inlays of ivory and green predominating. Electric heaters were built in, so that Their Majesties could adjust the temperature, while for the summer, electric “waving” fans were provided. Modern comforts supplied in the royal saloon even included the provision of electric cigar-lighters. Queen Alexandra’s bedroom was draped in delicate pink with silver-plated fittings. Adjoining was Her Majesty’s dressing room, similar in design, but with inlaid satinwood furniture, while next to it was another dressing room, no less ornate, for the use of Princess Victoria.

His Majesty’s annual schedule meant commuting between the royal residences of Buckingham Palace, Sandringham (a palace he disliked, but from it, he could go to Newmarket for the races), Balmoral, and Windsor. In between, he attended shooting parties in Scotland, supper parties and the theatre in London, all interspersed with romantic rendezvous. For example, he made several rail trips to Gopsall Hall, Leicestershire, not because its garden was where George Frederick Handel had composed the music for the Messiah but to meet with Lillie Langtry, a popular actress of the period and his mistress.

Then there was also holidaying on the Continent by train in the summer. As Prince of Wales, he travelled across Europe to advise his nephew the Kaiser or to discuss the Entente Cordiale with the French or to visit the spa at Marienbad to cure his obesity. Once he went as far as Bad Ischl near Salzburg, to speak to the aged Emperor Franz Josef.

For travelling over the European railroads, Edward VII also owned and maintained a royal saloon, a twelve-wheeler that was the longest in use then, which was kept in the same shed at Calais with his mother’s. At a time when every royal family, from the grand dukes of the Russian court to Indian maharajahs, maintained their own trains in Europe, this was not unusual. Edward’s saloons would be hitched to the famed Orient Express, and his portly figure (travelling as the Duke of Lancaster) was commonly seen in the company of one of the beauties of the day. The Prince of Wales journeyed on occasion with Princess Alexandra, in three private coaches, all built for comfort with enormous armchairs, thick pile carpets, toilets, and spacious cupboards for the luggage. His Royal Highness’s personal compartment was furnished in the style of a gentleman’s smoking room — leather armchairs, card tables, books, newspapers, drinks, and cigars. The King took with him thirty servants and his fox terrier, Caesar, who, the staff knew, could do no wrong. In his rail travels, His Majesty made the Baie des Anges at Nice, with its palm trees and ornate hotels, so fashionable that the French renamed it the Promenade des Anglais. On April 4, 1900, the royal saloon would be the scene of an attempted assassination of the Prince of Wales when the train was leaving Nord Station, Brussels.6

In contrast with Edward’s own Canadian railway tour of 1860, when his son and daughter-in-law, the Duke and Duchess of Cornwall and York (later King George V and Queen Mary) arrived in September 1901, the Canadian Pacific Railway had grown into a multi-modal transportation giant, operating trains, ocean liners, banks, telegraph companies, hotels, and ferries across the world. A royal train was assembled to take the Duke and Duchess across Canada from Quebec City to Vancouver and back to Saint John, New Brunswick, and Halifax. It was conducted by Andrew Rainie of Saint John, the oldest conductor on the Intercolonial Railway, and the carriages were provided by the rival Canadian Pacific Railway.

Each of the nine cars was 730 feet long, lit by electricity and equipped with electric bells, telephones, and facilities for hot and cold water. “Cornwall,” the day coach, had an expansive observation platform at the rear, and its glass door opened into a reception area and an apartment decorated in Louis XV style. The entire room, except the framing and half the sidewalls, was constructed of plate glass to give the royal party an unobstructed view. From the reception area, a winding corridor led to the Duchess’s boudoir, which was upholstered in silk, its walls hung with original oils. The dining room walls were panelled and adorned with a number of armorial bearings, including those of His Majesty the King and of Their Royal Highnesses the Duke and Duchess, as well as the coat of arms of the Dominion of Canada. Entered through a vestibule with soft green plush curtains, the night coach, “York,” contained the bedrooms and bathrooms of the Duke (in grey and crimson), the Duchess (in blue), the ladies and gentlemen-in-waiting, and the servants. “Canada,” the third coach, was a compartment car with five staterooms, a dressing room, lavatory and shower bath, and parlour. The remainder of the train consisted of “Sandringham,” the staff dining car, and the sleepers “Australia,” “India,” and “South Africa,” which held the secretaries’ office and medical dispensary. The royal train was always preceded by the viceregal train carrying the Governor General and his staff, the Prime Minister, Sir Wilfrid Laurier, and members of Parliament, and the premier of whichever province it was then in.

British Railways Board

The Britannia Class 4-4-0 locomotive that hauled King Edward’s VII’s royal train in 1902.

Between 1914 and 1941, no new royal saloons were built and, with some modifications, the existing royal trains served both Edward VIII and George V. Queen Victoria’s old saloon would be used as the hearse coach for both her funeral and that of her son, Edward VII. The period of opulence had ended with the Great War, and with hard financial times, railway companies were reluctant to spend on decor in the hope of attracting royalty. Also, the motor car was usurping the train for short Royal Tours.

PA-38861

The Prince of Wales (centre) standing next to a Canadian National Railways passenger car, Ottawa, Ontario, 1924.

King George V and Queen Mary made extensive use of various carriages owned by the LNWR, GWR, and the LBSC. Of the many industrial areas they visited by train — the pair loved to press switches and unveil plaques — particularly historic was their trip to the huge railway yards at Crewe on April 21, 1913: no member of the royal family had until then ever been to a rail yard. During the First World War, Their Majesties continued their inspection trips by train, but now to munitions factories and hospitals. Because they did not wish to stay overnight at homes of friends (for one thing, all the domestic staff in the big houses were now in uniform), they slept more and more on board the royal train and even bathed on it — so much so that, in 1915, two bathtubs, silver plated and encased in mahogany, were installed in the dressing rooms of the saloons used by Their Majesties. On April 28, 1924, the King personally drove a Castle class locomotive, number 4082, appropriately named “Windsor Castle,” from the Swindon Works to Swindon Station.7 Plaques were mounted on the side of the cab to commemorate the occasion.

Through his short eleven-month reign, Edward VIII never warmed to the royal trains — they represented the formality of his father’s era. His Majesty preferred instead fast cars (preferably Canadian) and aircraft. But his dislike did not extend to those trains he used overseas. On his first visit to Canada in 1919, accompanied by Captain Alan Lascelles (later to be Governor General Lord Bessborough’s secretary), the handsome, unattached, twenty-six-year-old Prince Edward set out on a two-month rail tour across Canada. “I progressed westwards in a magnificent special train provided by the Canadian Pacific Railway. My quarters were in the rear car, which had an observation platform. This last . . . while providing me with a continuous view of the varied Canadian landscape had however the drawback of making me vulnerable to demands for ad lib speeches from the crowds gathered at every stop,” he remembered. “Getting off the train to stretch my legs, I would start up conversations with farmers, section hands, miners, small town editors or newly arrived immigrants from Europe. It was the first time that a Prince had ever stumped a Dominion.” In 1923, he came back for a seven-week tour, and even tried his hand as driver at the controls of a Canadian Pacific 4-6-2 locomotive. The Prince returned to visit his Alberta ranch several times, including in 1927 to celebrate the country’s Diamond Jubilee of Confederation.

His Royal Highness was not as fortunate with rail travel in Western Australia when on tour there in 1920: as his train entered Bridgetown, it derailed. Only by luck did the heir to the throne escape unhurt. But when he returned home on HMS Renown and stepped ashore at Portsmouth on October 11, the royal train was waiting to take him to Victoria Station, the front of the 4-4-0 locomotive decorated with the Prince of Wales’s feathers. It was a mark of respect well meant by the railway but wholly unappreciated by the Prince.

On the Continent the Prince of Wales made frequent trips to Vienna, preferring the anonymity of the Orient Express to the royal train. The Wagons-Lit Compagnie converted Sleeping Car No. 3538 for his private use, with a salon and shower.8 On one trip, the Prince claimed he was in Vienna consulting a physician for a chronic ear problem, when His Highness and friend Major Edward “Fruity” Metcalfe were seen at the Viennese night spots Chat Noir and Cocotte, and rumours spread that they were meeting with prominent Nazis. Edward VIII had no liking for either Sandringham or Balmoral, and did not use trains as much as his father or grandfather, choosing to isolate himself in his residence at Fort Belvedere, which could be reached only by car. Even a Mediterranean cruise had unfortunate results: the hostility of the Italian Fascist government prevented him from embarking on the yacht Nahlin in Venice, and his party had to travel by train to Yugoslavia, “an indescribable journey that I subjected myself to,” he wrote (blaming the Foreign Office for this inconvenience), to meet the yacht at the little fishing village of Sibenik.

PA-210047

Visit of Their Majesties King George VI and Queen Elizabeth. Her Majesty is accepting flowers from a little girl. The royal party has just alighted at Beavermouth, B.C., July 1939.

One of the rare occasions when Edward VIII did use a British train was on November 18, 1936, when he toured depressed areas in Wales. Scorning the royal train — and even the red-carpet treatment — His Majesty travelled in a special GWR carriage, arriving bareheaded in the freight yards, and completing much of the tour by car. His flair for public relations asserted itself this one final time and, moved at the plight of the destitute miners, he declared, “something must be done.” However, Edward knew he would not be the man to do it, and had already told his brothers, his mother, and the prime minister of his intention to abdicate. After his abdication, there were no more royal trains and the new Duke took the Orient Express from Austria to France to be married at the Château de Candé, near Tours. This time, a retired Orient Express employee recalled, to escape the media circus, or “hounds” as Wallis Simpson termed the press, his meals were taken by tray into an ordinary compartment, where the former king ate off two suitcases balanced between the seats.

During her son’s brief reign, it was Queen Mary who kept the old LNWR Royal Train in use, and after Edward’s abdication, it became a perfect means for King George VI, Queen Elizabeth, and the two little princesses to vacation at Balmoral. The children were thrilled at sleeping on a train that had been built for their beloved grandfather, who had doted on little Elizabeth. As soon as he acceded to the throne, as if exorcising his brother’s irresponsibility, George VI immediately paid visits by train to Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland.

Unlike his brother, the new king had always enjoyed trains. As Duke of York, he had travelled on the Orient Express to Belgrade in 1922 to attend the marriage of King Alexander of Yugoslavia to Princess Marie of Romania. Shortly after his own marriage, the Orient Express had taken him and his bride, the Duchess of York, to Belgrade for the christening of Crown Prince Peter. In 1925, they attended the centenary celebration of the opening of the Stockton and Darlington Railway, the first passenger railway in Britain. On August 6, the following year, His Royal Highness drove the first train on the fifteen-inch-gauge Romney, Hythe and Dymchurch Railway in Kent. On October 20 he visited the Southern railway works at Ashford and even rode on the footplate of the locomotive Lord Nelson. Little did he know of the marathon railway adventure to come.

Through the winter of 1938-39, London and Ottawa were busy working out the details of a royal visit to North America. As Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain had just returned from Germany with Hitler’s assurance that there would be no war for at least a year, it was considered safe to allow Their Majesties to leave the country and drum up support from Britain’s closest Dominion and its mighty neighbour. The royal train trip would be from one coast of Canada to the other and back, with a side trip to Washington and New York. The plan was that Their Majesties would visit every province and provincial capital, with day trips in large cities and whistle stops in smaller ones. The train would pull off into quiet (and secret) sidings at night so that all on board could sleep. If the city to be honoured was in the riding of a powerful Liberal politician, so much the better, for then, as now, the photo opportunity for a politician of greeting Their Majesties at the station was worth thousands of votes. This precipitated local politicians, mayors, Rotary clubs, and society hostesses to badger the Prime Minister’s Office for a few precious royal minutes and to warn of dire consequences in the next election if that did not happen. Where the train could not stop, the plan was that it would slow down and Their Majesties would drop everything and rush out to the platform and wave, affording the throngs of locals who had been waiting for hours a quick view of the King and Queen on the rear platform.

It was a heavy schedule, exhausting for everyone involved with the royal party —the Mounties, the press, the ladies-in-waiting, the hairdressers, the postal workers, and everyone on board. But no one was to work harder than Prime Minister Mackenzie King, who at every stop got off the train first and then rushed over to the royal car to greet Their Majesties, welcoming them to whichever city they were in and introducing them to the local politicians, their wives, and the aldermen.

PA-211025

Joyce Evans, daughter of the Port Arthur City Clerk, presents a bouquet to the Queen, as W.L. Mackenzie King and C.D. Howe look on, May 23, 1939.

The grand railway tour was to begin on May 18, when Their Majesties would be driven from the Citadel at Quebec City to the railway station. Engineer Eugène Leclerc of Quebec, who had worked on the Royal Train in 1901 and had been in CPR service between Quebec City and Montreal for forty-eight years, had the honour of being the first engineer. The Royal Train would leave for Montreal, making sure it stopped on the way at Trois Rivières, Quebec, Premier Maurice Duplessis’s hometown. After Montreal it was on to Ottawa, then Toronto, with a brief stop at Kingston and Cobourg on the way. Through the Ontario highlands it would go, and then along the north shore of Lake Superior to Port Arthur, C.D. Howe’s riding. The train was to stop at Raith, Ontario, for servicing but only slow down at Kenora before arriving in Winnipeg. The Prairies would follow, with stops at Brandon, Regina (named for the King’s great-grandmother Victoria Regina), Moose Jaw, Swift Current, Medicine Hat, Calgary, and Banff, where the royal party was to rest. Through the Rockies they were to stop at Craigellachie, Salmon Arm, and finally Vancouver. On the return east, it was Vancouver to New Westminster, through the Fraser Valley to Jasper for a rest, and then on to Edmonton. They would stop at Wainwright, Biggar, Saskatoon, Waitrose, Melville, Portage la Prairie, and Sioux Lookout, then travel through to Toronto and then west to Guelph, Kitchener, Stratford, Chatham, and finally Windsor, where the royal party would stay overnight — quite a coup for up-and-coming local MP Paul Martin. In the evening the royal train was to arrive at Niagara Falls. Then it would traverse the undefended border into New York State, go down to Washington, and then make for Manhattan. At the New Jersey shoreline, the train would halt to allow Their Majesties to take a United States naval vessel to The Battery, Manhattan. The train would be waiting for them at Hyde Park Station, where the President’s home was, to take them back to Canada. Across the border, they would go through Levis, Rivière-du-Loup, and on to New Brunswick. They would reach Prince Edward Island by a destroyer, and then the royal train would be picked up again at New Glasgow. The last stops would be Truro and finally Halifax, where a liner would wait to take them home.

There were only two organizations in Canada capable of planning and executing the logistics of such a complex visit: the Canadian Pacific Railway and the Canadian National Railway. Both railways were already proficient at VIP tours across Canada. CPR President Sir Edward Beatty set out on one annually, in his luxurious carriage “Wentworth” — named, like his golf club, with his middle name — to inspect his domain. More frequently, the CNR would take the Governor General about in his private carriage. With the first company private — and most of its shareholders British — and the second wholly owned by the Canadian government, it might be assumed that Mackenzie King (who loathed the CPR and its president) would give S.J. Hungerford, president of the Canadian National, a free hand in the whole royal trip. But in a typically Canadian gesture, both railways divided the trip — on land and sea, in hotels and lodges — between them, so that, if Their Majesties arrived at a Canadian National station, as in Montreal at Jean Talon, they would leave from Windsor Station, where the CPR had its headquarters. From Vancouver to Victoria they crossed on a CPR ferry the Princess Marguerite, but, on the return voyage, they used the government-owned ship Prince Robert. The trip west would be made on CPR tracks, the return journey on CNR tracks. Neither railway was to be given preference, and the King and Queen were told not to mention either in speeches or interviews. So important were the two railway presidents that, when Their Majesties stepped on shore at Wolfe’s Cove on May 17, after the Prime Minister and Minister of Justice Ernest Lapointe, the next to be introduced were Beatty and Hungerford.

C-014455

When the royal train couldn’t stop: Their Majesties leaning out of the carriage, May 1939.

Of the royal train’s twelve cars, six were prepared in the Point St. Charles shops of the Canadian National Railways and six at the Angus Shops of the Canadian Pacific Railway. The former included the Governor General’s two private cars, in which the King and Queen travelled; No. 7, which the Lord-in-Waiting and the Lord Chamberlain used; the Canadian National compartment cars “Atlantic” (No. 6) and “Pacific” (No. 4), in which other members of the royal party were accommodated; and one of the new Canadian National diners, the most modern type recently put in service by the Canadian National and capable of seating forty people. The Canadian Pacific Railway also supplied the private car “Wentworth” (No. 5), which was used by the Prime Minister and his official staff; the Chambrette car “Grand Pré” (No. 8), which accommodated the Train Office and provided sleeping quarters for a number of officials; a Chambrette car (No. 3) for the personal servants of Their Majesties and the Mounties; a compartment sleeping car (No. 9), which was used chiefly by the protective forces, but also included a barber shop; a combination baggage and sleeper for part of the train staff (No. 11); and a baggage car (No. 12). In one end of the baggage car, an electric power plant was installed to furnish power for the passengers’ needs and to provide a refrigerated storage compartment for food supplies.

The King’s sitting room in Car No. 1 of the royal train used in the 1939 tour.

CN003705

The map in the sitting room on which Their Majesties plotted their progress across Canada in the royal train.

CN003788

Canadian National Railways locomotive No. 6400, which hauled the royal train in 1939.

The King and Queen travelled at the rear of the train, as far from the noise and soot of the locomotive as possible. Car No.1 contained two main bedrooms with dressing rooms and private bath, a sitting room or lounge for the King and Queen, and two bedrooms for members of the Royal Staff. The living room was furnished with green chairs and apricot-coloured upholstery. It had a radio and small library that was appropriately stocked with books by Canadian authors such as Bliss Carmen, Mazo de la Roche, and Stephen Leacock. Popular authors of the day like Pearl S. Buck, Anne Morrow Lindbergh, and of course John Buchan (the Governor General) were also represented — as was a translation of Hitler’s Mein Kampf. Family photos and mementos were scattered about, including two little canoes that had been given by a First Nations community for the princesses. There was also a set of specially designed maps of North America that rolled up and down like blinds. In the tiny but fully equipped dining room, the china was a white Limoges pattern with bands of maroon and gold surmounted by an embossed crown.

Perhaps reflecting his naval upbringing, His Majesty’s rooms were in blue and white chintz. Close at hand were his field glasses and cine camera — he was constantly running in to grab it and record sightings of moose and deer that he thought his daughters would like to see. His bathroom was done in pale blue. The Queen’s sitting room was blue-grey with damask coverings and curtains of dusty pink. Her bedroom was in soft peach with brocaded satin drapes. On her bedside table were her The Book of Common Prayer and a pile of the ghost-story books that she loved. Her bathroom was in lavender.

Car No. 2 had a large lounge, as well as an office, a dining room and kitchen, and two bedrooms with a bathroom for members of the Royal Staff. Car No.7 had two main bedrooms with bath, lounge, dining room, kitchen, and also a bedroom for servants. The cars “Pacific” and “Atlantic” accommodated the ladies-in-waiting and other persons of Their Majesties’ staff. “Atlantic” had six rooms with lounge and a shower. “Pacific” had five rooms, a lounge, and a shower. The lounges on “Atlantic,” “Pacific,” and car No. 7 were used as sitting rooms for all members of the royal party.

The exterior colour scheme of this “Buckingham Palace on wheels” (so dubbed by the press) was royal blue, with silver panels between the windows and a horizontal gold stripe above and below the windows, the blue extending above the windows to the roof line, which had a gun-metal colour. The last two cars of the train, cars Nos. 1 and 2, were dubbed “The Married Quarters” by the press. Their two carriages, in which the King and Queen travelled, bore the royal coat of arms in the centre of each car below the windows. The other cars in the train bore the royal cypher and crown in the centre below the windows, and a royal crown at each of the blue stripe between the top of the windows and the roof line. All of the cars were air-conditioned, which was more and more appreciated as the Canadian summer began.

It had been on the King’s express command that a buzzer was installed between the engine and the royal cars, and the locomotive engineer had instructions that, whenever he saw a crowd at any station ahead where they were not going to stop, he was to press the buzzer and slow down. This was a signal for Their Majesties to run out to the observation platform and wave. Through the trip, Her Majesty spent much time arranging the bouquets of flowers that were handed to her at every station. The King and Queen also spent time talking, reading, or playing games of solitaire. They also listened to the radio9 and talked on the phone to London and their daughters — facilities were provided at all stops for an outside telephone service. On one such phone call, Princess Elizabeth assured them that she was looking after Margaret, and her sister burst out with the news that she had passed her Girl Guide tracking test. Outside Port Arthur, the royal couple heard that Her Majesty Queen Mary had had an accident in her old Daimler. In between calls, His Majesty worked away on his “boxes,” the dispatch cases from London.

The royal train heads through the Rockies on its way to the Pacific coast during the 1939 Royal Tour.

The royal train was preceded, throughout the tour, by a pilot train, its purpose to protect and serve those on the train behind them. It carried the press, photographers, members of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, and excess baggage that could not be accommodated on the royal train. The pilot train consisted of twelve cars, of which the Canadian National furnished seven. These included: one drawing-room sleeper, and three baggage cars. Two of the baggage cars were specially equipped to carry the baggage of the royal party, and the third baggage car was converted into a unit that included an electric power plant for generating all electric current, a darkroom for photographic purposes, and a postal-service section. The Canadian Pacific furnished five cars, including two drawing-room sleepers, a diner, a combination baggage car and sleeper, and a lounge car (“River Clyde”), which occupied the rear of the pilot train.

The Canadian National prepared locomotives for hauling the royal train, a 6400 type,10 a 6000 type, and one “Pacific” type, all finished in royal blue. Weighing 660,080 pounds, 95 feet long, and 15 feet high, the Canadian National 6400 steam locomotive had been built by the Montreal Locomotive Works in 1936 and, with the help of the National Research Council, was planned with an aerodynamic design that could prevent smoke from obscuring the engineer’s vision and could also reduce costs. The final bullet-shaped configuration, the result of wind-tunnel tests conducted in Ottawa, was so streamlined that it was often mistaken for a diesel locomotive. In addition to these, a CN oil-burner was used for hauling it through the mountains. The Canadian Pacific prepared two of its new Class H-1-d 4-6-4 locomotives for the royal train, which were the Hudson type, 2800 class. The Royal Hudson 2850,11 reconditioned at the CPR’s Angus Shops in Montreal, hauled Their Majesties across Canada, the first time that one engine had made a continuous journey of this length. Specially refitted and decorated for the occasion, the Canadian Pacific locomotive was a mass of shining stainless steel, royal blue, silver, and gold. The semi-streamlined engine bore the Royal Arms over the headlight, and Imperial Crowns decorated each running board. The crest of the Canadian Pacific appeared beneath the window of the cab and on the tender. The general decorative scheme comprised a background of deep blue on the underframe, the smoke-box, the front of the engine, and all the marginal work on the engine and tender. The sides of the tender, cab, and running boards were painted royal blue. The jacket of the locomotive, its handrails, and other trim were of stainless steel with gold leaf employed on the engine numbers. With His Majesty’s approval, the Royal Arms and replica crown were applied to all forty-five of the CPR’s H-1-c, H-1-d and the H-1-e 4-6-4s built between 1937 and 1945, and they became known as the “Royal Hudsons.”

The only time Their Majesties did not travel on the royal train was in New Brunswick between Fredericton and Saint John, where the track wasn’t strong enough to take it. A smaller, lighter train, consisting of a drawing-room car and four day-coaches, was used instead.

At a time when most of Canada seemed to live beside or near the two main railway lines, everyone had a good chance of seeing the royal train. Their Majesties met the famous, like air ace Billy Bishop, actor Raymond Massey, and the Dionne quintuplets, and the First People of Canada, like representatives of the Ojibway, Blacks, Stoneys, and Sarcees — some of whom had met the King’s father in 1901. They heard “God Save the King” sung many times in English, fewer times in French, and twice in Cree. Obviously missing their own daughters very much, they had lifted up to their carriage balcony dozens of bewildered children, and once at a remote station, Her Majesty, seeing two mothers with their babies, rushed into the kitchen and ran out with a bag of cookies for them. They met the future of the country through thousands of Boy Scouts and Girl Guides, many chosen because they were thirteen-year-olds like Princess Elizabeth (a Girl Guide herself), and they met its past, shaking hands with seven holders of the Victoria Cross. The press did not need to look far for copy and anecdotes abounded. At tiny La Station du Côteau, Quebec, the Queen made His Majesty remain still and pose for a little girl who was struggling with a box camera. Later, at the White House, Her Majesty delicately tried to eat the first hot dog she had ever seen with a knife and fork until President Roosevelt leaned over and advised, “Just push it straight into your mouth, Ma’am.”

PA-209847

Crowds wait for the royal train at Kitchener, Ontario. Boys placing coins on track over which it will pass.

When she learned the house prices at British Pacific Properties in Vancouver, Her Majesty wondered aloud if even she could afford to live there.12 The pair got off to visit dozens of veterans’ hospitals, placed wreathes on a dozen memorials, and must have planted a forest of trees. The blue train stopped at all major Canadian cities as well as specks on the map for water. Such a one was Fire River, Ontario (population twelve), where Her Majesty asked a trapper, “How cold does it get here in the winter?”

“Sixty-five below, Ma’am, and the snow, she’s six feet deep,” was the stoic reply.

When the royal train crept into Halifax on June 16, having covered 8,377 miles, in its freight compartment was a variety of gifts. Among them were the two tiny birchbark canoes for the princesses, dozens of stamp albums (everyone knew that the King, like his father, was a keen philatelist), twelve-pound cheeses, braided gauntlets from Duck Chief of the Blackfoot, a silver desk telephone, a solid gold trylon and crystal glass perisphere (with a thermometer in the trylon) from the New York World’s Fair, and a portrait of the late King George V by Sir Wyly Grier.

When the Empress of Britain docked at Southampton, the party boarded the old LNWR Royal Train for Waterloo Station. There they were met by Princess Alice of Connaught, and the Countess and the Earl of Athlone, all of whom had viceregal connections with Canada. Also on the platform was the Canadian High Commissioner Vincent Massey, another future Governor General. At Waterloo, the King and Queen boarded a landau for the ride to the palace, and as it emerged from the station, they were visibly moved by the cheering crowds outside. Through Trafalgar Square and the Mall, massed ranks of spectators applauded, the King noticing some carrying signs that said simply, “Well Done.” The Queen later told Prime Minister Mackenzie King, “The tour made us! It came at the right time, particularly for us.”13 A New York Times headline summed it all up: “The British Take Washington Again.” The North American rail tour had given His Majesty the confidence he would need to face the rigours of the war that was just around the corner.

C-080958

Prince Philip in the cab of the royal train locomative, kamloops, B.C., October 1951.

At the start of the Second World War, the old LNWR train built in 1902 was repainted the same colour as other trains, so that it would not stand out. As George V and Queen Mary had done, Their Majesties began tours of munitions factories and army camps and — with the Blitz — of bombed cities. Having slept on the train en route, they could appear at bomb sites in Coventry and Nottingham the morning after an air raid to comfort survivors and chat with Civil Defence workers. Everyone understood that the old train would not withstand a direct hit by a bomb or even shrapnel, and in the event of a German invasion, the saloons would splinter before a machine-gun attack. It was, of course, more likely that the train would be caught in an air raid, and the safest place was thought be in a tunnel. At the first sound of a siren, the train was to make for the closest one, remaining there until the “all clear” was sounded. Because of the threat of invasion, three new twelve-wheel cars were built for the royal family by the LMS at Wolverton: the King’s saloon (No. 798), the Queen’s saloon (No. 799), and one for the brake, power generators, and accommodation staff (No. 31209). The old LNWR royal saloons were withdrawn and later given to the National Railway Museum in York. Gone too was the ornate Victorian decoration; in its place were massive steel armour plates, including armour-plate shutters for the windows. Inside, the basic design was similar to the 1902 LNWR saloons, but they were now meant for extended day and night use. The walls, curtains, and carpets in the royal compartments were finished in pastel colours to provide a “country house” touch, contrasting with the armour plate outside. A rudimentary form of air-conditioning was attempted, with ice stored in boxes under the floor. It had to be frequently changed. Both saloons remained in use with the royal family until 1977, when they were sent into retirement. Today they stand next to their LNWR predecessors at the National Railway Museum.

Also made in 1940 were two special saloons by the GWR. Without sleeping accommodations, they were used for daytime trips by the royal family, as well as by Prime Minister Winston Churchill and General Dwight Eisenhower. After the war, both continued to be used by Her Majesty the Queen Mother to go to the races at Cheltenham and, now restored, one is at the Birmingham Railway Museum and the other at the Didcot Railway Centre.

At 4:15 p.m. on November 20, 1947, a very special royal train was preparing to pull out of Waterloo and the station masters at Clapham Junction, Surbiton, Woking, and Basingstoke were told to phone as soon as it passed their stations. There were also to be standby locomotives and crews waiting at Woking and Basingstoke. The main part of the train would be two Pullman cars called “Rosemary” and “Rosamund.” At the termination of the train at Winchester, a chalk mark was to be made at the exact spot at which the footplate of the engine (a Lord Nelson class) stopped at the down platform. A signalman with a red flag was to stand on the platform side of the engine at the chalk mark to ensure that the train halted exactly at the appointed place so that the red carpet could be put down. The whole railway — indeed, in the frugality of post-war Britain, the whole country — was participating in this ride. For this was the honeymoon train for Her Royal Highness Princess Elizabeth and Lieutenant Philip Mountbatten, RN, ready to take them to Lord Mountbatten’s home, Broadlands, in Hampshire. The young couple arrived at the station directly from their wedding reception at the palace in an open carriage. Concealed beneath the rugs were hot water bottles and the bride’s favourite corgi, Susan, with whom she couldn’t bear to part.

As His Majesty King George VI became ill, he tired more easily, and going to or from an event, he slept more often on board the royal train, his equerry asking that speed be reduced so as not to disturb His Majesty’s sleep. After he died on February 6, 1952, at Sandringham, his remains were conveyed on February 11 from Norfolk for the lying-in-state in London and on February 15 from Paddington Station for the burial at Windsor. The same saloon had been used as a hearse vehicle for the funerals of Queen Alexandra in 1925 and King George V in 1936. The sides were painted black, with the King’s coat of arms mounted centrally on each side, while the roof was finished in white.

On January 1, 1948, all the railways in Britain were nationalized but the royal family’s LMS Royal Trains were unaffected. Two saloons were built for Princess Elizabeth and the Duke of Edinburgh. Thus, when she became queen in 1952, Her Majesty inherited three royal trains: the 1941 LNWR armoured train, the 1940 GWR daytime train, and the two saloons. The Queen used her mother’s saloon, 799, while Prince Philip used the former king’s saloon, 798. All three trains were hauled by the Lord Nelson-class locomotives, each of which was decorated with the royal plaques above their smoke boxes.

In 1955, Wolverton Carriage Works built a new saloon for the royal children, Prince Charles and Princess Anne. No. 2900 was fitted out in nursery furniture and nicknamed “the nursery coach” by the railway staff. By the end of the 1970s, the last of the old LNWR coaches that had been built in 1941 had been retired and the royal train was very much a product of British Railways. The present royal train came into operation in 1977 with the introduction of four new saloons to mark the Queen’s Silver Jubilee. The carriages were built in 1972 as prototypes for the standard Inter-City Mark III passenger motor carriage and subsequently fitted out for their royal role at the Wolverton Works, where much of the work on the royal train has been done. The Queen and Prince Philip were both consulted as to design, as seen in the inward-opening, double-door entrance vestibule at the end of her saloon. The windows in the doors opened inward so that Her Majesty could take leave of her hosts after the doors had closed. Other smaller royal trains were still in use for daytime journeys or by Her Majesty’s guests. Visiting royalty or heads of state were met by the royal train whether they entered the country at one of the Channel ports or at Gatwick Airport. Unlike her father and grandfather, Her Majesty has travelled by ordinary trains (first class), and on March 7, 1969, she rode the Underground from Green Park to Oxford Circus, a trip that surely brought back memories of when her governess Crawfie had taken her and her sister on the Underground while the King and Queen were in Canada. Characteristic of his appreciation of history, on September 27, 1975, Prince Philip opened the National Railway Museum at York, where so many of the saloons made for royalty by such companies as the GWR, LMS, and LNWR have been preserved.

But what the world’s television viewers remember most are the great events in the royal family’s (and the nation’s) history in which the royal train is featured. One such event was the funeral of Earl Mountbatten of Burma on September 5, 1979, when a combined royal and funeral train took Her Majesty and the Earl’s body from Waterloo to Romsey. A happier occasion was the honeymoon special on July 29, 1981, when the Prince and Princess of Wales used the train to travel on the same journey from Waterloo to Romsey to spend part of their honeymoon at the Mountbatten estate, Broadlands, as the Queen and Prince Philip had also done. This time, able to follow their every move on television, thousands of well-wishers crowded the route, cheering as the train was led by the locomotive “Broadlands,” which bore at its head the code “C.D.” — the initials of the royal couple.

The royal train enables members of the royal family to travel overnight at times when the weather is too bad to fly, and to work and hold meetings during lengthy journeys. The designation “royal” train is actually incorrect, because the modern train consists of carriages drawn from eight purpose-built saloons, pulled by one of the two Royal Class 47 diesel locomotives, named “Prince William” or “Prince Henry.” The exact number and combination of carriages forming a royal train is determined by factors such as which member of the royal family is travelling and the time and duration of the journey. While it is owned by Railtrack, an American company, it is operated by the English, Welsh and Scottish Railway Company. Journeys on the train are always organized so as not to interfere with scheduled service, and royal train drivers are drawn from an elite pool working in the railway industry. One of the most demanding skills they have to master is the ability to stop at a station within six inches of a given mark, a feat that fascinated Prince Charles when he was a boy.

Fitted out at the former British Rail’s Wolverton Works in Buckinghamshire, the carriages are a distinctive maroon, with red and black coach lining and a grey roof; they include the royal compartments for sleeping and dining, and support cars. On board are modern office and communications facilities. The Queen’s saloon is seventy-five feet long, air-conditioned and electrically heated, and has a bedroom, a bathroom, and a sitting room with an entrance that opens onto the platform, as well as accommodation for her dresser. The Duke of Edinburgh’s saloon has a similar layout, with a kitchen. Scottish landscapes by Roy Penny and Victorian prints of earlier rail journeys hang in both saloons. A link with the earliest days of railways is displayed in the Duke of Edinburgh’s saloon: a piece of Brunei’s original broad-gauge rail, presented on the 150th anniversary of the Great Western Railway.

For the Queen’s Golden Jubilee celebrations in 2002, the royal train came into its own, covering 3,500 miles across England, Scotland, and Wales, taking Her Majesty from as far south as Falmouth in Cornwall and as far north as Wick in Caithness, Scotland. The train was to be sold off after the Queen and her family had made use of it during the Golden Jubilee celebrations, but Buckingham Palace told Members of Parliament that there were benefits for the Queen in allowing a new train to replace the old one. Helicopters were often grounded by bad weather or found it difficult to land at night, at dawn, or at dusk. But a train allowed the Queen to go to the very centre of cities, stay on board overnight, and have meetings or entertain people on board. Prince Charles, who used the royal train more frequently than the others, argued (through his staff) that he enjoyed the isolation and convenience it brought to a heavy schedule. It gave him invaluable time to read his briefings and prepare speeches, all the while travelling towards his destination.

The future of the royal train is once more in doubt as the government has launched an inquiry into its cost to the taxpayer, which in 2003 was £596,000 for seventeen journeys, or £35,059 per trip. When Prince Charles took the royal train overnight to Cumbria to launch a rural revival project, the trip cost £16,729. A royal train journey taken by the Prince of Wales from London to Kirkcaldy, Scotland, to visit a farm ecology centre cost £37,158. The Queen and the Duke of Edinburgh’s trip from Slough to Lincoln for the annual Maundy Service in April 2002 cost £34,263. Their journey from London to Bodmin to visit the Royal Cornwall Show cost £36,474. The cost of maintaining and using the train is met by the royal household from the Grant-in-Aid that it receives from Parliament each year for air and rail travel. It cost taxpayers £872,000 in 2003, compared with £675,000 in 2002 and was used for a mere nineteen journeys, four more than in the previous year, averaging 827 miles per journey. To mitigate the expense, the royal family has indicated that it had cut the cost of its rail travel by 64 percent in the last five years, reducing the number of coaches from fourteen to nine. Of the five carriages of the royal train that were given up, three were sold for £235,000, while the other two were kept for spare parts. The remaining nine carriages were also offered for rent. But in three years, only the Foreign Office has rented — and only once, in 1998. Lack of conference facilities and dining facilities is cited as the reason, but the train is probably seen as rather too pretentious for modern conferences. In any case, unused for three-quarters of the year and then used only around twenty times, it would require airing out and dusting. Expensive to maintain and underused, it could be replaced by a commercial service, and its critics point out that using a helicopter or renting a single carriage and connecting it to the end of a regular train would be cheaper.

Its future in doubt even before 9/11, a journey by the royal train is now a security official’s nightmare. The miles of tracks are impossible to secure, and the train is old and slow. Industrial action by railway employees (while not directed against Her Majesty) has disrupted royal journeys many times. Vulnerable especially when the royal passengers are asleep, the royal train itself is heavily protected by uniformed members of the royalty and diplomatic protection squad armed with 9-mm Austrian Glock machine pistols. But having just lost her beloved HMY Britannia, Her Majesty is devastated at the thought of surrendering the very last exclusive and familial means of royal transport left.

Ultimately, what might save the royal train is its nemesis: the motor car. As Britain becomes increasingly urbanized and its road system even more congested, traffic jams will multiply. Only a train will allow Her Majesty to get from the middle of one big city to another comfortably, easily, and on time.