Читать книгу Wings Across Canada - Peter Pigott - Страница 16

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCourtesy of Canadian Pacific Airlines Archives

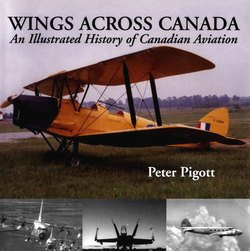

Junkers 52/1m “CF-ARM.”

JUNKERS 52/1M

Goering had three, all painted red, all named after his idol, Manfred von Richthofen. Hitler was presented with one in 1934 and cherished it. When his staff tried to upgrade him to the four-engined Focke Wulf Condor, he showed no interest and then angrily refused, saying he was used to his dependable old Ju 52. The aircraft that would bomb Guernica, drop paratroops over Crete, and reinforce the German Army at Stalingrad survived the war to be built in France and flown by British European Airways on its London to Belfast route. Gawky, slow, noisy, and draughty, the Ju 52 was known to its German crews as “Tante Ju,” “Iron Annie,” or, in the later part of the war, “The Corrugated Coffin.” Even now, wrecks are found in the jungles of South America and New Guinea, and in Norwegian fjords.

Dr. Hugo Junkers held that there was a sufficient market for such a large cargo plane and presented his corrugated metal, cantilever monoplane Ju 52/1m (for single engine) to the public at Tempelhof Airport on February 3, 1931. But both Lufthansa and the Luftwaffe wanted an aircraft of that size to carry seventeen passengers, troops, or bombs rather than freight, and persuaded Junkers to convert it to the three-engined Ju 52/3m, the first of which flew on March 7, 1932. Thus, only seven of the single-engined version were built, and only one was exported — to Canada.

When Prime Minister R.B. Bennett canceled the federal mail contracts in 1930, James Richardson looked to increase his company’s cargo-carrying capacity instead. Impressed by the versatility of his Junkers W33/34s, he purchased Junkers’s giant single-engined Ju 52/1m. With its corrugated duralumin skin (unable to obtain aluminum, Junkers developed his own “Elektron” metal) and three main wing spars, the Ju 52 was ideal for bush conditions. Its large flaps allowed it to land in restricted areas. Its massive undercarriage tolerated takeoffs from the most primitive airfields. It could carry its own weight into the air (from three to eight tons), and its systems were so elementary that it could be repaired in the bush — the only hydraulics were the brakes.

Courtesy of UNN

Both Junkers at Collins, Ontario, 1934.

The choice of power plant was optional, and Richardson sent his engineering manager, Tommy Siers, to tour the Junkers plant at Dessau, Germany. Siers decided to replace the standard Junkers L88 engine with a 12-cylinder, liquid-cooled, 685 horsepower Bavarian Motor Works (BMW) engine. The Junkers was shipped to Montreal on the S.S. Beaverbrae and, when assembled at the Fairchild factory in Longueuil, caused a sensation. Its cargo hold was 21 feet in length; 5 feet, 3 inches wide; and 6 feet, 2.75 inches high. It had nine doors and hatches and, until the Second World War, registered as CF-ARM, it was the largest aircraft in Canada.

Richardson expected that it would substantially increase revenue by being able to fly more freight at lower prices and that all heavy hauling contracts would now come to Canadian Airways Ltd. But the BMW engine proved so unreliable that in its first year of service, the Junkers sat idle for 297 days. Engine problems continued over the years until, in 1937, it was re-engined with a Rolls Royce Buzzard engine. There were other problems not as easily corrected. The corrugated “Elektron” metal, which the pilots said gave the appearance of being in a Nissen hut on wings, cracked after a few hard landings. The double wing design (Junkers used full span ailerons and slotted flaps trailing behind and below the wing’s leading edge) was an ice magnet. A few minutes flying collected ice in the gap between the wing and aileron and locked the controls. Like their Russian, Swedish, and German counterparts, the Canadian pilots learned to waggle the wings at intervals to prevent complete (and fatal) loss of control.

With its size and idiosyncrasies, memories of the Junkers lived on long after its use. Canadian Airway’s engineers never forgot that the engine was cooled with ethylene glycol and that “it was hell of a job draining that thing, heating the glycol and putting it back.” Others remembered CF-ARM as “an awkward old cow on the water because the pilot couldn’t operate the throttle, watch where he was going, and operate the water rudders at the same time. She wasn’t bad in the air, except she was slow. She had hinged flaps and floats as big as all outdoors! Standing beside those floats, the step was above you! Some of the places we went into didn’t have docks that could handle her.”

But CF-ARM survived to be sold to Canadian Pacific Airlines in 1941 and remained operational until 1943. With the Nazis in power, Richardson decided against buying any more Junkers, but those built in Spain flew there (and in the Spanish and Portuguese African colonies) long after the war had ended. Such was CF-ARM’s importance to Canadian aviation history that the Western Canada Aviation Museum purchased a Spanish-built Ju 52/3m. It was flown over to Winnipeg and, with funding from the James Richardson Foundation, converted to single-engine status to resemble CF-ARM and put on display with the original Rolls Royce Buzzard engine.