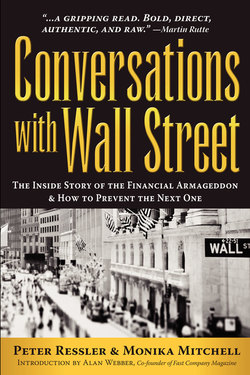

Читать книгу Conversations With Wall Street - Peter Ressler - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

The Street

ОглавлениеI had no idea what to do after college. I thought about working on Wall Street, but I was not sure what I could do since I never felt too comfortable with the complexities of bond math. All I knew was I could sell just about anything. A friend told me about executive search, saying, “You sell jobs to people. You’re good with people.” I interviewed for a big recruiting firm, AJ Consulting, located in midtown Manhattan. It specialized in banking and I was hired on the spot. The president’s name was “Joel” and we hit it off immediately. “Headhunting,” it was called in those days. The cannibalistic nature of it was confirmed when Joel advised: “Visualize every potential candidate with a dollar sign across his face.”

Joel was a great guy, a fifth degree black belt in karate. We soon began working out in the dojo together. He was two different people, one in business and the other in the arts. At the office, anything goes was the strategy; do whatever it takes to close the deal. There was no talk of honor or ethics: it was simply go for the kill and get the job done. There was a saying I learned in those days that is still used in the financial industry today: Eat what you kill. It embodied the savagery inherent on the Street. On the dojo floor, Sensei Joel was a different man. The martial arts world was the essence of honor and ethics. The irony was here we were learning how to kill, yet the code was to use our skills only as a last resort in self-defense. It was repeated over and over that we were never to attack first. You carried deadly weapons in your hands and your feet, yet the hope was to never have to use them.

Back in the bullpen at AJ, it was dog-eat-dog. It was a commission-only job, so the burden was on us to produce. When I learned how much bankers made, I almost fell off my chair. I never knew anyone who made $150,000 a year before. I was stunned to find out that I would get paid a percentage for every deal I closed. My first commission check was $2000—more money than I had ever seen at one time before. All I had done was make a phone call. I was hooked. I sat next to a guy who later became a huge success in search. I called him Clint because he would pick up the phone and shout, Make my day! Clint was irreverent and funny, and we had a great time working together. We competed heavily to see who would hit the top of the board first. We were neck and neck on production. Our ambition made our numbers better; it became part of the game. Every night I would hit the local bar, knocking back a few beers and shots of gin. It was a way to make the stress of the job more bearable. At least that was how I justified it. I did not want to face the truth that I might have a growing drinking problem. One thing about Clint had always bothered me. I would hear him lie repeatedly to candidates: “Oh yeah, great opportunity for advancement,” despite knowing full well this was untrue. Then I would hear him deceiving clients the same way: “No, he’s not ambitious. He doesn’t want to move up.” When he hung up, I would ask him, “Why do you have to lie like that?” He replied without a beat: “I just tell them what they want to hear.” The year was 1982; Gordon Gekko was only a dream away. Clint and I developed client lists from our different styles. We went on to represent some of the same firms in different sectors.

I became the top producer at AJ despite my increasingly heavy drinking. There were days when I came in after partying all night, and it was obvious I had not slept. The President and CEO basically let me have free rein; after all, I was twenty-five, and this was part of our world. Booze fueled the Street. I met clients after work and we drank to our success. There was camaraderie in it. As long as I produced, no one seemed to care. They knew I was hungry and driven to make money. I was the first one in the office and the last one home. I had found a place where I belonged. My firm gave me a corner office, a secretary and a bigger payout. I could not believe how lucky I was. One thing I loved about the job was meeting lots of different people. Every day I met new people and expanded my network, many of whom are still my friends today. Unlike Clint, money was not my only motivator. For me, the candidates were regular guys who were building a future—not numbers on a page. I felt a kinship with them and a responsibility to safeguard their career. To my clients I felt a fierce loyalty and always strove to find the best talent to build their business. These were the ingredients for my rapid success. People got to trust me and rely on me to put their interests first. It was funny how Clint and I had two contrasting ways of doing business, yet we were both producing almost equally. After two years of working for smaller commercial banks, I landed my first major investment banking client: Lehman Brothers. The future was wide open. Nothing could stop me now, nothing except the increasing burden of my alcoholism. Despite my great fortune, I was lost. I had no purpose to my days other than making money—no deeper meaning to my life.