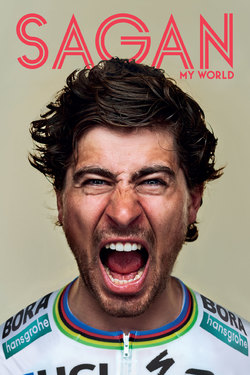

Читать книгу My World - Peter Sagan - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление2015

WINTER

If there are a hundred riders on the start line of a race, there will be a hundred stories to be told at the end. A hundred careers could yield a hundred different books. Everybody is remarkable, but nobody is special.

I tell you this at the beginning of my story because it’s important to remember that everybody has a story. Mine isn’t more important than anybody else’s, but it is different. Just like everybody else’s story is different from mine, and different from each other’s.

My story has changed since the start of my career. It’s changed over the past three years, and it will change over the next. It will change before I get to the end of this book, as will yours. Let’s face it, some of our stories will have changed while I’ve been writing this sentence.

What I’m trying to say is that I can’t tell you my life story because my life is happening and changing every day, just like yours, just like everybody’s. I’m only 28, so I’m hoping to be sitting in a big leather armchair, smoking a smelly pipe, and stroking what’s left of my wispy white hair by the time I tell my life story. One thing I can certainly tell you is what it has been like to be UCI World Road Race Champion for three years, and that’s something that you can only hear from me, I suppose. Nobody else has been champion for three years in a row.

Life can change in the blink of an eye. Doors close, doors open. You can win, or you can crash. You can fall in love, or you can lose somebody close to you in an instant.

Even with that undeniable truth in mind, January of 2015 saw me standing at a significant crossroads.

I was 24 years old. I was from Žilina, Slovakia, but now I lived in Monte Carlo. I’d been a professional cyclist for five years, in which time I’d won 65 bike races, been champion of my country four times, and won three green jerseys in the Tour de France.

But now, for the first time in my career, I was changing teams.

I suppose I ought to go back a bit further to explain how I got to this moment. Back to the beginning.

As a kid, I loved riding my bike and winning races. People love the stories about me turning up to races on bikes borrowed from my sister or bought for a few koruna from a supermarket, wearing trainers and a T-shirt, and beating everybody. I’m not saying those stories aren’t true, but really, they weren’t such a big deal. Slovakia was an emerging country, booming after decades dozing behind the Iron Curtain, and now let loose from our awkward embrace with the Czechs thanks to the universally popular “Velvet Divorce.” All of us kids were living the high life and screaming at the top of our lungs. I had two older brothers, Milan and Juraj, and there was my sister, Daniela. My dad would drive me all over the place to race bikes. Way beyond Žilina and beyond Slovakia, too: Poland, the Czech Republic, Austria, Slovenia, Italy . . . we’d just go. Mountain bikes, road bikes, cyclocross bikes—it didn’t matter. I just wanted to race. Because I was winning, and I liked it.

I was winning enough races that the professional teams started to take notice. In my last year as a junior, I went for testing with Quick-Step at their academy, which had nurtured so much young talent over the years. I stayed at the anonymous building that could easily be mistaken for a factory or the regional office of a nondescript company, knowing that the corridors of this place had echoed with the young voices of many champions over the past 20 years or so. In the end, it was those huge numbers of young cyclists that became an obstacle in my progress. They process literally hundreds of kids through there every year and keep tabs on thousands more juniors across the globe, hoping to unearth the next Merckx, Kelly, or Indurain. Neither my race results nor the numbers I produced in their tests were enough to lift me clear of the other hopeful juniors. They told me to work hard in the Under-23 category for the next couple of seasons, and they would continue to monitor my progress.

It wasn’t meant to be negative, but it felt like it. Which is why, when the Liquigas team came along and said they’d take me on board straightaway, I couldn’t wait to say yes. They didn’t need to wait for me, and I sure as hell wasn’t going to wait for a call from Quick-Step that might never come.

There were quotas on Under-23 teams in Italy regarding foreign riders, so I carried on riding in the Slovakian national setup for mountain bike and road races from Slovakia to Italy to Germany to Croatia. I might not have been riding the Tour de France in a Liquigas jersey, but I was 19, and I was a pro-continental cyclist earning 1,000 euros a month. It was pretty cool.

In July 2009, Liquigas called me up to meet the main squad at the Tour of Poland. Led by Ivan Basso, there were some guys there whom I would become close to over the years, guys like Maciej Bodnar; Daniel Oss, who is back with me at BORA-hansgrohe now; but most of all Sylwester Szmyd, who has been a good friend for many years and is now my coach.

The introduction was Liquigas’s way of telling me: “You’re in.” Even though I was still only 19, there were to be no more Under-23 races, no more barreling round Europe in a Slovakia jersey, no more mountain bike racing. I was to be a full-time professional on the ProTour circuit.

Liquigas got me an apartment in San Donà di Piave near Venice. It was small, but it was mine. My brother Juraj came to stay, and so did Maroš Hlad, my soigneur from back home. This was the beginning of Team Peter, a little unit of friends who could all rely on each other in any situation. I now had an agent, too: Giovanni Lombardi, a classy ex-rider who’d led out Erik Zabel to many of his green jersey victories. Giovanni, or Lomba as we affectionately call him, was the first to see the potential of Team Peter and the one man who has done more than anybody else to make it a reality. The first real appointment of Team Peter was to bring Juraj on board as a pro at Liquigas, and that was thanks to Giovanni. He knew my brother was good enough to hold a pro contract in his own right, but he also knew he would fight like crazy to protect me on the bike and off it, too. Juraj, Maroš, and I stayed together in Veneto, moving closer to the mountains so we could vary our training more. They were great days, and we were there for two years until I moved to Monaco on Giovanni’s advice.

My first race as a professional was the Tour Down Under in 2010. I’d never been to Adelaide before, but I wasn’t completely unfamiliar with Australia. Four months earlier I had raced at the 2009 UCI Mountain Bike World Championships in the nation’s capital, Canberra, where I took fourth in the U23 men category. I loved the heat of Adelaide in January, riding out every day in shorts and a jersey without having to worry about arm warmers or the like. It’s another country with its own distinctive smell. Eucalyptus, or gum trees, as the locals say. If I catch a scent of that anywhere in the world, I’m transported back to sunny days in the southern hemisphere, those hot days where the earth seems to be flattened by the heat from above.

It’s a gentle race to do, too. As well as the weather, there are no long transfers between stages, no packing your bag every day, and a nice hotel that the whole race is staying at. As with any career, there are tedious parts to life as a pro cyclist. Somehow, during the Tour Down Under, those elements are less apparent. As I’ve grown older, I’ve appreciated the laid-back nature of Australians in general, too. Nothing is too much of a problem. They have a look in their eyes that seems to say: Why so serious?

There was a bit of rough and tumble down under. I raced, sprinted, fell off, but overall thought, Well, if I’m only 20 and have never raced before, and these guys are all 30-something and have been doing it for years, I reckon I might be able to win a few of these one day.

I thought that day had come as soon as we got back to Europe. I wasn’t meant to be riding a big race like Paris–Nice this soon, but Bodnar was sick, and the team decided to throw me in for the experience with no expectation of me. Central France was freezing, but on just the second stage into Limoges, there was a crash 500 meters from the line as the different sprint trains got in each other’s way. As ever, I was sprinting on my own, watching the wheels, and the crash left me with a gap. I smashed straight through it, heading for the line, but just as I thought I was going to be a winner for the first time, I realized that I’d gone too soon, and the quick Frenchman William Bonnet came over me with the line in sight.

I was disappointed for about two minutes, but then I realized that I had nearly won in my first European race, and a big race at that. The wins would surely come.

And they did. The first one was the following day when I won from a small group after our attacks had whittled down the peloton over some hilly country. It was like being back in Žilina: a flat grey sky that seemed to merge with the horizon and snow flurries that caused the stage start to be brought forward 50 kilometers into the race.

Three days later I was at it again; this time attacking 3 kilometers out when everybody was waiting for the sprint and arriving in Aix-en-Provence two seconds before everybody else. The question that I would hear from the press most days in my pro career was asked for the first time that afternoon: Was I a sprinter or not?

That Paris–Nice gave me my first points jersey, too. As I stood on the podium next to Alberto Contador, who had won the race with his usual attacking panache, I thought: You could get used to this, Peter.

I picked up another points jersey at the Tour of California, and the season flew by. A year later and I was picking up that Californian green jersey again, then taking three stages in my first Grand Tour, the Vuelta, where I managed to complete the whole three weeks. In all, I won 15 races in 2011 and 16 more in 2012.

The spring of 2012 was when I was really able to make my presence felt at the classics, where I was unable to get a win but finished in the top ten at Milan–San Remo, Gent–Wevelgem, and the Tour of Flanders, and even managed to get on the podium at a hilly race like Amstel Gold. I was being asked if becoming a classics specialist was blunting my sprint, but that was just daft. Sprinting to win a stage of a race where most of the combatants’ first priority is to get through to the next day unscathed is an entirely different proposition to taking a Monument like Flanders or Roubaix home with you. For a start, it’s a case of “shit or bust.” You win, or you go home; there’s no second chance waiting tomorrow, meaning that crazy do-or-die efforts are the order of the day. Add to that the distance of each race. Milan–San Remo can be 300 kilometers long, and the bunch smashes it out of Milan and over the Turchino Pass like greyhounds out of the traps. The stamina that’s needed to be strong after seven hours of racing is not the same as the stamina a track cyclist needs to blast past somebody on the Olympic Velodrome after a couple of laps. Suddenly “sprinter” is a much more complicated term than it would originally appear.

The last tool in the locker that you need for classics success is experience. The classics are steeped in history, with every berg, corner, or stretch of cobbles known like the streets around their homes by the men, like Cancellara or Boonen, who have been winning them for many years. In contrast, most stage races are a moveable feast. When you come to a finish in the Tour de France, you’ll be trying to remember the roadbook from when you looked at it in the team bus for the first and last time that morning. Is there a bend? Was that corner a left- or a right-hander? How far from there to the line? Is it uphill? Will there be a headwind?

Put all that together and you just need one thing: all the luck in the world.

I got an opportunity to show the world that I could sprint in July when I went to the Tour de France for the first time.

On a night out in Žilina with Milan and all my old friends, for some reason—and that reason is probably beer—we were all doing a chicken dance: elbows out, knees out, waddling round the bar like the overgrown teenagers we were. Now, as Gabriele Uboldi, my road manager, will be the first to tell you, seeing as he is so often on the wrong end of them, I am always motivated by a wager. When the first stage of the Tour hit the Côte de Seraing, one of the steep ramps that Liège–Bastogne–Liège goes over each year, all I could think of was that if I hit the top first, I could do the chicken dance over the finish line like I’d promised the guys at home.

Fabian Cancellara went for broke on the lower slopes, and I nearly popped my eyeballs out to get on his wheel. He was wearing the yellow jersey by virtue of winning the prologue the previous day and was determined to make it two wins out of two. As I got up to him on the steepest bit of the climb, I looked back and saw that only Edvald Boasson Hagen had made it with us. The rest of the Tour was stuck to the lower slopes. As we reached the top, with a few hundred meters left, Cancellara tried hard to get me to do a turn, but I kept my head down on his wheel, knowing that if I could get him to lead out, I fancied my chances of coming around him. Boasson Hagen was similarly glued to my wheel, probably thinking the same thing, and the bunch was closing in. Just when I thought I might lose my nerve and attack, fearing we would be caught with 200 meters to go, thankfully Cancellara opened up the sprint.

He did so at the perfect moment for me, just before the pace dropped off, and I soared around him to take my first Tour de France stage win, freewheeling enough to be able to do the chicken dance all the way over the line. Cancellara wasn’t happy with me, initially because he felt I had ridden his coattails to the win, which was true, but he was a superstar, and I was a rookie. Then that celebration really got up his nose, taking it as a personal snub and a sign of disrespect.

By the time we reached Paris, I had my first Tour de France green jersey, and I’d been able to add the Incredible Hulk and the Running Man to my celebrations. I would have won more, but I’d run out of ideas for victory salutes. At least Cancellara knew by then it was nothing personal.

The 2013 season was my best year to date, picking up 22 wins in all sorts of races on all sorts of terrain, making me the most successful cyclist on the ProTour circuit that year. Or should I say the “winningest,” like the Americans? It’s a horrible word, but it’s more accurate. Who is to say that winning 22 races is more successful than winning one Tour de France and 17 other races, like Chris Froome did that year?

I’d initially thought it was going to be the year of the second place when I went through March with second at Strade Bianche, Milan–San Remo, E3 Harelbeke, and the Tour of Flanders. Planted in the middle of that run was my first classics win. At last. Belgium was bitterly cold and apparently Gent–Wevelgem was nearly cancelled, but instead it was shortened by 50 kilometers. That obviously suited me, what with stamina (in my opinion) being the older riders’ strength, and I found myself at the sharp end of the race all day. With 4 kilometers to go and my breakaway rivals wondering how they were going to beat me in the sprint, I attacked instead and won on my own, popping some wheelies to please the crowd who’d been risking hypothermia to see me win.

I suppose in retrospect, 2014 wasn’t so bad, with a third Tour de France points jersey in a row to show for my troubles and seven wins along the way, but in truth it was hellish. I was realistic enough to know that my upward trajectory to this point had been such that I might need to take stock. I was well-known now and heavily marked whenever I raced, which was bound to bring my win numbers down a bit. I was focusing more and more on the big titles like Flanders and Roubaix, which are always going to be harder to win—that’s the whole point—and everyone needs a bit of luck. I could even deal with treading water for a season if that’s what it was going to take to move on in the longer term.

But this wasn’t treading water. This was shit. I was rubbish. I was exhausted all the time. I had won that Tour green jersey again, but 2014 was the first time I’d ridden a Tour de France and not won a stage. No silly celebrations. Shit, no normal celebrations. I felt I was letting everybody down: my friends, my family, Team Peter, my teammates, Cannondale (as Liquigas had become), everybody.

It was time for a change. Either that or go home to Žilina and give up.