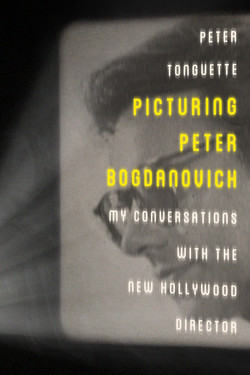

Читать книгу Picturing Peter Bogdanovich - Peter Tonguette - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPART 1

“Call Me Peter, Peter”

The Giants were my delight, my folly, my anodyne, my intellectual stimulation.

— Frederick Exley, A Fan’s Notes: A Fictional Memoir

But how seldom two imaginations coincide!

— Saul Bellow, The Adventures of Augie March

I dialed the number his assistant had given me.

Brrring.

No answer.

Brrring.

No answer.

Brrring.

No answer.

For some reason, calling Peter Bogdanovich for the first time for an interview made me feel like Tom Sawyer.

Could it have been because I was so young? Not Tom Sawyer young, but close enough. When I called Peter Bogdanovich on the night before Thanksgiving in 2003 (the date must have some sort of cosmic significance, but for the life of me I cannot imagine what it might be), I was several months’ shy of my twenty-first birthday. I had a right to be nervous. If I measured myself against Peter Bogdanovich, as I often did, I was supposed to have done something by that age.

When he was twenty-one, he was already well on his way to the fortune and glory he would later gain as the director of a batch of extraordinary films that were all the rage—with both the critics and the public—in the early 1970s. The native New Yorker—born on July 30, 1939, to Borislav (a painter) and Herma (a homemaker and maker of frames)—started early. At the age of fourteen, while a student at the Collegiate School, he began penning frighteningly perceptive movie and theater reviews in his column “As We See It.” This anticipated his subsequent career writing feature articles for Esquire and New York, among other august publications.

But the prodigy was not consumed with writing alone—oh, there was more.

Acting was his first passion. His “earliest performances,” he wrote, were recitations of poetry and stories at dinner parties thrown by his parents: “After the meal they would ask me to recite … poems like Poe’s Annabel Lee’ or ‘The Raven,’ or Whitman’s ‘O Captain! My Captain!’ or Robert W. Service’s ‘The Shooting of Dan McGrew’—or to read a short story like Poe’s ‘The Tell-Tale Heart.’”1

Soon, though, he moved out of the dining room and onto the boards.

In an introduction to Bogdanovich’s collection of essays Pieces of Time, his editor at Esquire, Harold Hayes, noted with pride that Bogdanovich was all of fifteen when he became an acting student of Stella Adler—“having lied about his age and cut his gym class to make time available.”2 His classes with Adler—no matter the, ahem, fraudulent means through which they were obtained—resulted in appearances on stage and on live television, making him a seasoned trouper when he was not yet out of short pants.

More: “In 1959, at nineteen,” Hayes continued, “he somehow managed to raise the money to stage an off-Broadway production of Clifford Odets’ The Big Knife.”3 Are you keeping track? Good: journalist, actor, stage director—and barely old enough to drive. He was not tranquil with his success, either. Hollywood beckoned. It would not be too many more years before he and his first wife—production and costume designer Polly Platt—headed from New York to California, armed with a little money, a plethora of contacts obtained through his writing career, and the general notion that they wanted to make movies—not just see them or write about them.

By the time he was twenty-one, then, Peter Bogdanovich had done his share of Big Things and was destined for even Bigger Things. Me? In between shoveling snow in my suburb of Columbus, Ohio, I was just trying to launch my writing career—not exactly the sort of thing that Harold Hayes would have considered worth commemorating in print.

Nonetheless, on that Thanksgiving Eve in 2003, I found myself dialing Peter Bogdanovich’s number and waiting for him—or anyone—to pick up. I imagined the phone ringing off the hook in his handsome Upper West Side apartment, the one I had seen in a photograph when the New Yorker profiled him the previous year, just as his most recent film, The Cat’s Meow, was about to come out.

On this night, however, it seemed that no one was home—or answering, anyway. I hung up. What to do? I had a backup plan. In case he did not pick up when I called at the appointed time, his assistant had given me a second number to try. It was, she told me, the number to his cell phone. I leaned back in my chair for a long moment. I grabbed the receiver and thought, What the hell—why not?

Brrring.

Brrring.

This time—improbably, because he still felt out of reach to me—he answered. “Yeah?” he said. He sounded impatient—a little testy. I did not know then that this was how he almost always answered the phone—“Yeah?”—no matter his mood, and that his tone was not unfriendly but quizzical. It suggested that he had … things … going on … important things. He simply wanted assurance that he was being interrupted for a damn good reason.

So: “Yeah?”

I gulped and began: Who I was. Why I was calling. When—ahem—we had been scheduled to talk.

He listened patiently, without saying a word in response, and I began to wonder if any of what I said rang a bell. Had his assistant bungled our phoner? When I finally stopped talking, he calmly explained that he was being driven home from the New York set of The Sopranos, the popular HBO television series on which he had the plum role of the Lorraine Bracco character’s psychiatrist. Could I call him when he got home in fifteen minutes? He was, it turned out, perfectly polite, asking only that I give him some time—you know—to walk in the door and turn on the lights and have a sip of water before I started grilling him.

Shoot, I thought to myself. I should have just waited.

You may be wondering why I was calling Peter Bogdanovich in the first place.

Ostensibly, I was interviewing him for an article I was writing about his films, but I have to level with you: this was a bit of a ruse. In truth, I had loved his movies for years, and I simply wanted to talk about them with him. My mind was overflowing with questions: How did he cajole Ben Johnson into taking the part of Sam the Lion in The Last Picture Show? Why did he open Paper Moon with a close-up of its young star, Tatum O’Neal? Was it just the way I saw it, or was They All Laughed more personal—more him—than anything else he’d ever done? If the only way I could ask him these (and many other) questions was by becoming a professional journalist and talking my way into an assignment to write an article about his work—well, so be it.

Let’s face facts: I began writing about movies in the hope that my job would one day give me an excuse to talk to Peter Bogdanovich. There are worse reasons to select an occupation, right?

I was, to put it bluntly, a fan—but if you knew all that I did, you would be, too. What was there not to like? Following his detours in print and on stage, Bogdanovich jumped into moviemaking with gusto, and he met with such instantaneous success—laudatory reviews, big box office—that it was as though the public and industry had been waiting for him. What took you so long? they might have been asking.

By 1971, when The Last Picture Show was released, it had been a rough few years for anyone who prized classical filmmaking and its attendant virtues. Tapping into the antiestablishment mood of some in the country, films such as Midnight Cowboy and Woodstock seemed to be multiplying—like a virus. For all their differences, they had much in common: they were morally incoherent and visually ugly, bearing scant relation to the art form built by the likes of D. W. Griffith, John Ford, and Orson Welles.

Into this noxious environment stepped Peter Bogdanovich, and the contrast could not have been more striking. Pauline Kael was never his most sympathetic critic, but she got one big thing right. “He has a real gift for simple, popular movies,” she wrote. “He can tell basic stories that will satisfy a great many people, and this is not a common gift.”4 Introducing Bogdanovich’s book Pieces of Time, Harold Hayes quoted a studio executive expressing a similar sentiment: “People don’t want to be reminded of their problems. They want to be diverted and entertained. They want a Paper Moon by Bogdanovich, not a reprise on the tragedy of Bobby Kennedy.”5

Recognizing an ally, veteran directors saw that Peter Bogdanovich was part of their tradition—“one of us,” as the cabal in Tod Browning’s great horror film Freaks says. But these were no freaks—these were the normal people, and Bogdanovich joined their ranks eagerly. He became a friend to Ford and Welles and many others, and the only thing that stood in the way of an apprenticeship with Griffith was that the maker of Intolerance and Broken Blossoms had died in 1948, when the future filmmaker was nine. Bad timing.

Director George Stevens, he said, sought him out and gave him a pat on the back: “You know what it’s about. These guys don’t know what it’s about. That’s why we need you.”6 Well, George Stevens wasn’t D. W. Griffith, but, still, he was the man who had made Shane and Giant and A Place in the Sun. “These guys” meant, of course, Bogdanovich’s peers—those much-honored filmmakers who emerged at about the same time he did, including Martin Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola, and William Friedkin—but the most honest of them knew that Stevens spoke the truth. “The last person to make classical American cinema was Peter,” Scorsese said. “To really utilize the wide frame and the use of the deep focal length. He really understood it.”7 Observed writer Judy Stone in the New York Times in 1968: “Peter is under 30, but he doesn’t identify with his own generation.”8

Howard Hawks immodestly pointed out that Bogdanovich, in his capacity as a journalist, “sat on my set for two and a half years and on Ford’s for two and a half years, so he learned a few things.”9 Yes, yes, Howard—he had studied well. But he also benefitted from a more hands-on opportunity that presented itself soon after he made it to California with Polly Platt: he was brought on as an assistant on Roger Corman’s low-budget biker film The Wild Angels. So when Corman—as a kind of thank-you present—told Bogdanovich that could direct a movie, Bogdanovich was raring to go.

Rebellion was in the air in 1968, and it usually took the form of the young rising up against the old. In his debut film, Targets, Peter Bogdanovich reversed the equation, pitting a chivalrous senior citizen against a murderous postadolescent.

The hero of the story is Byron Orlok (Boris Karloff), a star of antediluvian horror epics. As the film opens, we find Orlok watching his current effort (actually recut scenes from the Karloff flick The Terror) in a dingy screening room in downtown Los Angeles. With its shots of crows shrieking and floods washing away damsels in distress, what we see of The Terror looks remarkably démodé, and by the time it is all over, Orlok—sitting stoop-shouldered in the third row—has decided to call it a career. With murder and mayhem having become daily realities, who in their right mind would be spooked by such stuff?

Before Orlok can slink away into the night, however, he has to answer to Sammy Michaels (expertly played by Bogdanovich), a greenhorn writer-director with whom he had promised to collaborate on a future project. Sammy implores Orlok to think twice about hanging it up, but Orlok refuses to budge. In their stubbornness, however, they prove themselves to be two of a kind: with his conservative dress and respectful manner, Sammy looks as out of place as Orlok in the Southern California of the late 1960s. About the worst you can say about Sammy is that he rudely tells Orlok to hush when the two find themselves watching one of Orlok’s old films on television (another Karloff project—this one, though, far more creditable than The Terror: Howard Hawks’s top-notch thriller The Criminal Code).

The character of Sammy makes for a ready-made contrast to Bobby Thompson (Tim O’Kelly), a Vietnam veteran who, apropos of nothing, morphs into a serial killer. Like Sammy, Bobby is in his late twenties and sports a clean-cut appearance, but in every other way he is Sammy’s shadow. A dim fellow with a toothy, heartless smile, we first see him as he purchases munitions at a gun store across the street from the screening room where Orlok and Sammy haggle. Orlok goes out of his way to call Sammy “a sweet boy,” and one glimpse of Bobby explains why: in the world of Targets, civility and virtue are rare qualities indeed.

Yet the screenplay (written by Bogdanovich and Polly Platt, with uncredited rewrites courtesy of Samuel Fuller) avoids pinning Bobby’s crimes on his war experience. After all, unlike many of his comrades, Bobby has returned home in one piece and seemingly none the worse for wear. What—we might ask—does he have to complain about? His placid family life is also exempted from blame: the single-story suburban house he shares with his parents and wife may be bland and uninviting, but so are many other houses, and few of them incubate mass murderers. “We tried to avoid a specific reason,” Bogdanovich told Judy Stone. “We did a lot of research, and the most terrifying aspect of these crimes is that there is no answer. We can find no reason commensurate with the size of the crime.”10 Yet the not-so-subtle suggestion in Targets is that culture makes the difference: Sammy, with his appreciation of old movies, has it, whereas Bobby, forever gobbling Baby Ruths and listening to rock music, does not.

Bobby and Orlok encounter each other at the drive-in theater at which Orlok is to put in an appearance before sailing to retirement in England. Mayhem ensues when Bobby makes targets of those in the audience. With the police nowhere to be found, it is left to Orlok—unarmed and in a tuxedo—to confront Bobby. We suspect that their encounter will end in a blaze of bullets, but the film has a more clever—and more pointed—resolution in store for us. Cornered in a dark spot beneath the screen, Bobby sees Orlok loping toward him but becomes disoriented when he looks up to see a similar image of Orlok in The Terror. In his confusion, Bobby is left defenseless when Orlok approaches and slaps his face—an opprobrium far more humiliating than losing a gunfight. Bobby drops his rifle and curls up in a fetal position. Only a figure as virtuous as Byron Orlok could vanquish the likes of Bobby Thompson.

Peter Bogdanovich put his cards on the table with Targets: it matters whether movies have moral fiber or not. We imagine the young director concurring with the mother in Herman Wouk’s great novel Marjorie Morningstar, then only about a decade old: “Marjorie’s mother looked in on her sleeping daughter at half past ten of a Sunday morning,” Wouk wrote, “with feelings of puzzlement and dread.”11

“Puzzlement and dread”—three words that sum up Bogdanovich’s perspective on the modern world. Modestly budgeted and not well distributed, Targets might have made a difference had it been seen by more audiences.

Then came the hits.

If you were distraught over the state of the movies in the late 1960s and early 1970s, The Last Picture Show surely came as a welcome change of pace. Critic Roger Ebert observed that the film did not just take place in the past but somehow was of the past. “‘The Last Picture Show’ has been described as an evocation of the classic Hollywood narrative film,” Ebert wrote. “It is more than that; it is a belated entry in that age—the best film of 1951, you might say.”12 With its black-and-white photography and clean, traditional storytelling, who could disagree? Few did. Chosen for inclusion in the New York Film Festival, The Last Picture Show sold more tickets than some of the more au courant fare of 1971, such as Shaft and Straw Dogs, and was up for eight Academy Awards on Oscar night, winning a pair for the supporting performances by Ben Johnson and Cloris Leachman.

The film’s much-ballyhooed first shot reveals the dilapidated facade and unoccupied ticket booth of the Royal Theater in Anarene, Texas, in 1951. One look at it, however, and we are surprised that anyone bothers to change the marquee. Panning past the theater and the shabby storefronts that surround it, the camera reaches an intersection, deserted except for a blinking streetlight dangling precariously from above. We wonder: Do any residents remain in Anarene to actually go to the movies?

Cloris Leachman in The Last Picture Show. Courtesy Jerry Ohlinger’s Movie Material Store.

But this thoroughly desolate-looking beginning is, in fact, a bit of sly humor from Bogdanovich. There is plenty of action taking place in Anarene—romances, affairs, au naturel pool parties—but it is going on in private. High-school student Sonny Crawford (Timothy Bottoms) is setting up house with his football coach’s ashen-faced wife, Ruth Popper (Cloris Leachman), while his best friend, Duane Jackson (Jeff Bridges), is arranging motel-room assignations with his pretty, popular classmate Jacy Farrow (Cybill Shepherd), whom Sonny also desires.

The difference between exteriors and interiors—between respectability and immorality—is emphasized throughout the film. In a lovely early scene (absent in the original cut but later restored by Bogdanovich), we see Jacy as she drives Sonny and Duane home in her open-topped convertible. They peppily belt out the school song in the brisk autumn air, which is alive with feelings of friendship and innocence. Much later, however, when the class sings “Texas, Our Texas” at a graduation ceremony, the earlier scene’s wholesome esprit de corps is obliterated by the private conversation Duane and Jacy carry on under their breath; having struck out during their previous tryst, he is imploring her to go to bed with him just one more time.

Now, a lesser director—a more conventional director—would be making a point about how the prim-and-proper 1950s were really no such thing. But in adapting Larry McMurtry’s fine novel, Bogdanovich takes a more rigorous approach. Instead of reveling in the adolescents’ behind-closed-doors antics, he casts his lot with the few adults in the story who disapprove of them, especially the rugged, tough-talking cowboy Sam the Lion (Ben Johnson).

Even the film’s famous skinny-dipping scene has an unexpected tone of finger-wagging: the audience is saddened—disheartened—when Jacy capitulates after being pressured into getting undressed on the diving board. There is a devastating moment when, after hitting the water, she finds that the watch she is wearing—just given to her by Duane—has stopped. Jacy brings the watch close to her face to see if it is still working, shaking her wrist several times before realizing that it has died. Her expression suggests that she wonders if something inside her has died, too. Jacy’s scruples are sadly transient: one of her prospective beaus smiles lustily at her from the opposite end of the pool, and she returns the look. Her watch is forgotten, as is her fleeting regret.

Director Leo McCarey—the master filmmaker behind The Awful Truth and The Bells of St. Mary’s—once told Bogdanovich that he had long dreamed of making a movie that told the story of Adam and Eve. In fact, Bogdanovich, not McCarey, would be the better choice to direct a movie about the costs of eating from the tree of knowledge.

In the years following The Last Picture Show, Bogdanovich came to oppose the unchecked sex and nudity rampant in contemporary movies. “Could such legendary goddesses of the screen like Greta Garbo or Marlene Dietrich have maintained their hold on the collective imagination if they had been forced to bare all?” he later asked.13 His unpopular but persuasive position is not far from that of literary critic George Steiner, who wrote that “sexual relations are, or should be, one of the citadels of privacy,” but “the new pornographers subvert this last, vital privacy; they do our imagining for us.”14 Years later, when a tragedy in his personal life led Bogdanovich to testify in support of an antipornography ordinance in Los Angeles, he expressed regret over what relatively little skin was shown in The Last Picture Show: “Believe me, if I had that scene to do over again, we’d just as soon not do it naked, because it wasn’t really necessary.”15

Who could reach Sonny, Duane, and Jacy? Certainly not their hapless English teacher (John Hillerman), who in a slightly pitiful scene recites a poem by John Keats. The camera pans across the classroom, but the power of the language fails to distract Jacy from looking at her compact or Sonny from looking out the window:

When old age shall this generation waste

Thou shalt remain, in midst of other woe

Than ours, a friend to man, to whom thou say’st

“Beauty is truth, truth beauty”—that is all

Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.

No, the only one who can save them is Sam the Lion, who owns the Royal Theater and several other concerns in Anarene but whose primary function is as “the film’s teacher, law-giver, fount of values,” as the author Peter Biskind puts it in Easy Riders, Raging Bulls.16 At one point, Sonny, Duane, and others solicit the services of an obese prostitute for Billy (Sam Bottoms), a dull-witted boy. When Sam learns that Billy was roughed up during this encounter, he scolds the group: “You boys can get on outa here. I don’t want to have no more to do with you. Scaring a poor, unfortunate creature like Billy just so you could have a few laughs. I’ve been around that trashy behavior all of my life. I’m getting tired of puttin’ up with it.” Sonny feebly speaks up with an excuse, but Sam—in the scene’s first close-up—cuts him off: “You didn’t even have the decency to wash his face.” Sonny gulps, and Sam turns away.

For critic Clive James, this was just about Peter Bogdanovich’s best moment: “The great scene in his first great success, ‘The Last Picture Show,’ was when Ben Johnson told the normal boys off for their ‘trashy behavior’ in humiliating a half-wit.”17 Lincoln Kirstein once made the provocative remark that “ballet is about how to behave”—and cinema ought to be, too, though it seldom is. In their rare moral rectitude, Byron Orlok and Sam the Lion stand apart from the crowd.

Fittingly, The Last Picture Show reaches its climax not with the illfated elopement of Sonny and Jacy or even with Duane leaving town to serve in Korea. The story instead turns on the death of Sam the Lion. Even at this early stage in his career, though, Bogdanovich knew that a deathbed scene out of Camille would never cut it. The shock of Sam’s death could be imparted only if it were revealed quickly—almost offhandedly.

Having returned from a jaunt in Mexico, Sonny and Duane are looking for Sam when they accost an old-timer snoozing in a car. “Hey, where is everybody?” Sonny asks. “Why’d Sam close the café?” Then the news comes—like a bolt of lightning. “Oh, yeah—y’all been gone, ain’t ya?” the old guy says. “Been gone to Mexico. You don’t know about it. Sam died yesterday morning.” Sonny parks himself on the edge of the sidewalk as the talk moves on to the contents of Sam’s will (“Craziest thing you ever heard. He left you the pool hall, Sonny. What do you think about that?”). The camera moves in closer as Sonny looks to the theater and then to the blinking streetlight; the breathtakingly subtle editing conveys a mind driven to distraction by grief.

Peter Bogdanovich often speaks about his preference for long takes, but when he decides he must make a cut, few directors are better at carving a scene into pieces. For example, in The Last Picture Show he hopscotches among the mourners at Sam’s funeral—one person’s reaction is shown, then another’s. We see the waitress from Sam’s café, Genevieve (Eileen Brennan), standing beside Sonny and Billy. While the three are grouped together in the same shot, each is inhabiting his or her own little world. The disparate nature of sorrow is the point of the image. Genevieve, clutching a handkerchief, cries openly; Sonny looks forlorn but keeps his emotions in check; and Billy is, as ever, uncomprehending.

Directly across from Sonny is Ruth Popper, who strains to make eye contact with her young lover. A spate of shots and reaction shots show Ruth smiling at Sonny and Sonny declining to smile back. Overcome with anguish over the loss of Sam, Sonny can’t bring himself to be reminded of his dalliance with his middle-aged inamorata.

Finally, we see the Farrow family: Jacy and her parents, Gene (Robert Glenn) and Lois (Ellen Burstyn). Later, we learn that Lois and Sam were lovers, and the scene ends with Lois’s point of view. From her perspective, we see Sam’s casket being lowered creakingly into the earth. Then in a tender, lingering close-up, Lois punctuates her tears with a heavy sigh and shake of the head. She walks off in a wide shot—the first in the scene—as the others slowly scatter.

It is tempting to look at Bogdanovich’s next film—What’s Up, Doc?—as a peace offering to his rapidly growing audience: after putting them through the wringer with Targets and especially The Last Picture Show, he seemed determined to give them some belly laughs. A wild screwball comedy starring Ryan O’Neal as a dullsville musicologist and Barbra Streisand as wacky gal pal fit the bill.

Having traveled all the way from Iowa to San Francisco to attend a conference with his fellow musicologists, Howard Bannister (O’Neal), wearing a seersucker suit and a scowl and toting a plaid overnight case stuffed with igneous rocks, looks glumly bewildered as he waits for a cab. The rocks’ ancient music-making properties are the subject of Howard’s research, but their real purpose in the screenplay by Buck Henry, Robert Benton, and David Newman (taking off from a story by Bogdanovich) is as a metaphor for an academician weighed down by unwanted obligations. Foremost among these obligations is Howard’s demanding, completely unlovable fiancée, Eunice Burns (Madeline Kahn), who when she is not scolding her intended is babying him in her high-pitched shriek of a voice. For example, even as Eunice counsels Howard to project manly virility when he meets Dr. Frederick Larrabee (Austin Pendleton)—the head honcho of a foundation that will award a $20,000 grant to a winning musicologist—she is tying his bowtie for him.

Howard first encounters wily, winsome Judy Maxwell (Streisand) at the drugstore inside the hotel where Howard and Eunice are staying. Emerging from behind some shelving, she asks, “What’s up, Doc?”—but the question sounds more like a pass than a Bugs Bunny line. We already know that she is a one-woman wrecking crew: in an earlier scene, two motorcycles collide with each other as she innocently trots across the street. Yet we feel that Howard could benefit from a dose of character-building chaos. Tellingly, he wanders into the drugstore in search of aspirin to soothe a headache, but—in a good omen—he exits pain free, as if Judy’s presence, while destructive, functions as a kind of elixir.

Judy has already started presenting herself as Howard’s wife—a bit of wish fulfillment and a reminder that it is often the girls, not the guys, who do the romantic pursuing in Bogdanovich’s films. Later that evening at Dr. Larrabee’s dinner party, having rechristened herself Eunice Burns, or “Burnsy,” Judy charms the pants off of the good doctor, in the process elevating Howard from dark horse to shoo-in to get the $20,000. The real Eunice has been delayed, and although Howard has grown increasingly petrified of her imminent arrival, at a key moment he elects to keep the charade going. At last, Eunice puts in an appearance—kicking, screaming, and insisting on the veracity of her identity—and the camera moves in on Howard: “I never saw her before in my life.” Is it really a choice? Good times with Judy and big bucks from Dr. Larrabee or … what? Eunice? (“That’s a person called Eunice?” Judy says earlier, as though the name itself is unpalatable.)

Of course, the deck is stacked. With brick-red hair and a wardrobe of housedresses, Kahn arguably makes one of the least-alluring screen debuts in history—not that the screenplay gives her much to work with in the sexiness department. At one point, we find her reading a book with the title The Sensuous Woman (for pointers?) before disgustedly putting it down.

The simple truth is that Eunice does not stand a chance next to Judy, and Streisand—covered up in a trench coat and cap at first—grows ever more sultry as the film goes on. The morning after inciting a disastrous chain of mishaps that culminates in the fire brigade being summoned to the hotel, Judy reveals herself to Howard—like a genie springing from a bottle—from underneath a sheet covering a piano. In the film’s most romantic scene, Howard plays as Judy sings a slow rendition of “As Time Goes By.” They end up on the floor together, the result of Judy trying to lay a kiss on Howard and Howard backing off, but for once it does not seem like another Bogdanovich pratfall. Really, it’s almost as romantic as anything in Casablanca.

Of course, affaire de Howard and Judy is set against a serpentine backstory involving three other plaid overnight cases, each one of which gets confused with the other and all of which are being sought by a gallery of rogues, including an investigative reporter (Michael Murphy), a jewel thief (Sorrell Booke), and a government agent (Phil Roth). Everyone is tailing everyone else before the threads converge in a breakneck chase snaking through San Francisco. Near the end, a benevolent judge (Liam Dunn) is tasked with making sense of it all, but he would have saved himself a lot of aggravation had he bothered to ask if his own daughter—naturally, soon revealed to be Judy—was involved. By this point, however, Howard has realized that the unequivocal love she offers, even with its attendant danger, is just what the doctor—the doc?—ordered.

In some ways, What’s Up, Doc? was even more old-fashioned than The Last Picture Show; it concerned itself with nothing but good clean fun. “This would have been heresy a few years ago, and it still may be,” noted Variety, “but Peter Bogdanovich describes his latest (and third) feature, ‘What’s Up, Doc?,’ as a ‘G-rated screwball comedy without any socially redeeming values.’”18 Heresy maybe, but a hit definitely. Save The Godfather and The Poseidon Adventure, no film made more money in 1972 than What’s Up, Doc?. Even more significantly, it was beloved by the audiences who came to see it in droves.

New York Times critic Vincent Canby sarcastically observed that “the real mean age” of the audience he saw the film with at Radio City Music Hall was “about fifty-two and three months,”19 but that is surely an exaggeration. After all, a few weeks after the film opened, Warner Bros. took out an ad in Variety announcing the attainment of a record that could have been achieved only with the help of an audience consisting of all age groups: a “new single-day all-time record” of $65,398 for the Music Hall.20

But what would be wrong if the film did speak to an older generation? When I was seventeen, I went to a revival screening of George Sidney’s film version of Rodgers and Hart’s musical Pal Joey, starring Frank Sinatra and Rita Hayworth, and after it was over, I found myself exiting the theater amid a sea of retirees. Not far from me was a husband and wife of perhaps eighty, and it occurred to me that they could very possibly have seen Pal Joey when it opened in October 1957! I lingered for a moment on the sidewalk and tried not to be too obvious as I listened to their conversation.

“That’s the kind of movie that puts a spring in your step,” the husband said.

“They don’t make them like that anymore,” the wife replied.

It was all I could do not to interrupt and concur that step-springing movies like Pal Joey were indeed a thing of the past—that is, unless Peter Bogdanovich was on the set to say “action” and “cut.” He is a much better director than George Sidney, too.

“In the American cinema, he is the man of the hour,” said one writer soon before the release of What’s Up, Doc?,21 and when Paper Moon was released in the spring of 1973, that hour was extended. Little more than a year had passed since Doc and only eighteen months since The Last Picture Show, but here was Peter Bogdanovich again—back in theaters with a smash.

This was no everyday occurrence. To put it into context, imagine that Citizen Kane had been a blockbuster and that Orson Welles followed it with two additional films of comparable critical and popular appeal—all in the space of less than three years. You might interject that Citizen Kane was a work of Important Cinema, whereas The Last Picture Show, What’s Up, Doc?, and Paper Moon were … what, exactly? Granting that Doc was conceived and marketed as an overtly commercial work (“A screwball comedy. Remember them?” read the tagline), the remaining two-thirds of the triad fell somewhere in the middle of the highbrow-lowbrow spectrum: impeccably made and morally serious films that were nonetheless completely accessible.

Welles himself had the right idea when in conversation with Bogdanovich he labeled his young friend “a popular artist.” At first, Bogdanovich bristled at the designation, but Welles explained that it was intended as a compliment. “Shakespeare was a popular artist. Dickens was a popular artist,” Welles said. “The artists I personally have always enjoyed the most are popular artists.”22 Later, when several of Bogdanovich’s films started to struggle commercially, he remained “a popular artist”: they never failed with audiences for lack of trying. Bogdanovich always invited the strangers in the dark to see themselves in the story he was telling—even if, on occasion, only a handful of strangers showed up because of problems in marketing or distribution or both.

Before Bogdanovich agreed to direct Paper Moon, he came close to pulling off what would have been his greatest feat: to go along with his coming-of-age drama and his screwball comedy, he planned to direct a Western of unusual ambition. The news was heralded on the front page of Variety in February 1972: “Superstar western planned by Peter Bogdanovich for first of three pix for Warner Bros. will be his own original script, ‘The Streets of Laredo’ … with cast including John Wayne, James Stewart, Henry Fonda, Ryan O’Neal, Ben Johnson, Cybill Shepherd, and the Clancy Bros., Irish singing group.”23 After John Wayne got cold feet, and Bogdanovich saw no point in recasting a role conceived for a legend, the project was over—although the coauthor of the screenplay, Larry McMurtry, eventually spun a Pulitzer Prize–winning novel, Lonesome Dove, out of the material.

So Bogdanovich made Paper Moon—and as replacements go, he could have done much worse. An adaptation of Joe David Brown’s novel Addie Pray, the film is—not unlike What’s Up, Doc?—the story of one person in pursuit of another. Having made up her mind that lying, cheating, paternity-denying scalawag Moses Pray (Ryan O’Neal) is her father, orphaned eight-year-old Addie Loggins (Tatum O’Neal) spends the entire film trying to win his affection. Paper Moon takes the unfashionable but entirely convincing position that a daughter needs a father. That Moses is such a scoundrel certainly complicates the film’s current of patriarchy. But for Addie, any father—even one as unreliable as Moses—is better than none at all.

Of course, it is clear from the start that Moses leaves a great deal to be desired. He meets his purported daughter for the first time at the burial of her mother, a prostitute with whom he had a liaison. Standing with Addie at the gravesite are a minister with a voice that hymns were written for (“Rock of Ages” is sung at the makeshift service) and a coterie of kind-hearted old ladies who stew over what will become of Addie. Pointedly, Moses is not among the initial mourners. He shows his face late, bearing flowers pilfered from a nearby tombstone, and initially hesitates when it is suggested that he look after Addie until she can catch a train to St. Joseph, Missouri, where a distant relative is said to live. With his cheap suit, wide-brim hat, and insincere smile, the character is quickly, and brilliantly, sketched by Bogdanovich and O’Neal.

Not long after Moses has been shamed into caring for Addie, we learn how he puts food on the table: as the proprietor of the respectable-sounding Kansas Bible Company, he pawns copies of the Good Book to poor souls who have never placed an order in the first place. Scouring newspaper obituaries, he shows up at the doors of women recently widowed, claims that a late husband had ordered a customized Bible, and insists that a balance is due. The moment when Addie realizes what Moses is up to is a gem of visual storytelling. Waiting in the car while Moses does his usual song and dance for a widow named Pearl, Addie spots a folded newspaper in the driver’s seat. The name “Pearl” is circled in Pearl’s husband’s obituary, and when Addie snoops around in a trunk, she finds a stamp-and-ink set used to personalize the Bibles. The look of revulsion on Tatum O’Neal’s face as she puts it all together is not only very funny but reflects her character’s fundamental goodness.

Of course, Addie soon becomes Moses’s willing and energetic partner, pulling off quick-change maneuvers in front of unsuspecting dime-store cashiers, but she also injects an element of fairness into their schemes. For example, Addie assesses the socioeconomic status of their dupes before determining how much is to be charged for a given Bible. A well-fed elderly woman clutching a strand of fat pearls ought to pay more; a gaunt mother surrounded by a half-dozen scrawny children will get a discount.

In fact, we feel that Addie, in teaming up with Moses, is motivated less by nascent criminality than by a fervent wish to be near her sole surviving parent. Having been orphaned once, she cannot let it happen again. Similar motives inspire Addie to outwit a loose woman with whom Moses has shacked up, Trixie Delight (Madeline Kahn, as jiggly as a bowl of Jello in her satin blouse). In a brilliantly orchestrated sequence, Addie frames Trixie in the hotel where Moses has temporarily installed the gang. With the assistance of Trixie’s streetwise helpmate Imogene (P. J. Johnson—almost as good as Tatum O’Neal), Addie manages to entice a dopey front-desk clerk (Burton Gilliam, a one-of-kind bit comic player later reused in At Long Last Love) to meet Trixie in her room. When Moses finds the two of them in a compromising situation, he dumps Trixie, heartbroken over the betrayal.

Of course, we wish that Addie had a parent worthy of her—one like Byron Orlok or Sam the Lion or even “Frank D. Roosevelt,” as Addie calls the thirty-second president of the United States. She goes on and on about FDR—not, we suspect, for his policies or programs but for his warm parental manner. But Addie takes what she can get, and when she is finally deposited in St. Joseph, we understand why she is not tempted by the care of a benevolent relative or the comforts of a normal home: she wants her pa, even if it means a life of crime.

While the characters in Paper Moon treat the Bible with a notable lack of reverence—as a floppy black book to be written in and thrown about—few films better or more entertainingly illustrate the Fifth Commandment to honor thy mother and thy father.

When Tatum O’Neal won an Academy Award for her performance in Paper Moon, her acceptance speech encapsulated the ascent of the film’s maker: “All I really want to thank is my director, Peter Bogdanovich, and my father,” she said—as though no one else really mattered. Was she wrong or just imprudent?

To be sure, over the course of his first four films, Bogdanovich had assembled a top-flight crew (including cinematographer László Kovács, designer Polly Platt, editor Verna Fields, and production associate Frank Marshall) and a lively group of actors (including both O’Neals, Madeline Kahn, Randy Quaid, Duilio Del Prete, and John Hillerman), and it is impossible to overstate the importance of their contributions. Yet audiences were coming to see the work of one artist, not a collective, and the studios knew that he was their biggest selling point.

When What’s Up, Doc? opened in New York, the marquee gave the game away, as Bogdanovich later recalled: “The biggest kick I got was seeing my name on the marquee when I hadn’t even asked for them to put it there. My name circled the marquee: PETER BOGDANOVICH’S COMEDY.”24 The message was loud and clear: the director was the one who mattered to the public. The same thinking accounts for the prominence Bogdanovich was given in the trailers for What’s Up, Doc? and Paper Moon (and later for Daisy Miller and Saint Jack). There he is, front and center in behind-the-scenes footage—setting up shots, showing his performers how to play a given scene, and generally mugging for the camera.

“Hello,” he says to the camera in the trailer for What’s Up, Doc?, “I’m Peter Bogdanovich”—before pretending to forget the title of “this little picture we’re making today.” But none of the pictures were “little” as long as this was the guy who was directing them. The trailer for Daisy Miller, too, gets mileage out of the evolving Bogdanovich legend. A snippet from Paper Moon is shown before a voice-over solemnly intones: “Last year Peter Bogdanovich gave you the moon.” We see a shot of the director behind the camera of his latest film, as the voice-over continues: “This year, Peter Bogdanovich has made a movie in color: Daisy Miller, starring Cybill Shepherd.”

Paper Moon was the inaugural release of the Directors Company, a production company that Paramount Pictures put together for Bogdanovich, Francis Ford Coppola, and William Friedkin, affording them total control over their films if they kept their budgets reasonable. The idea, said studio president Frank Yablans, was to combine “such forceful talents as these with a climate where their creative skills can be utilized to their highest degrees.”25 Well, Coppola’s contribution to the Directors Company was the interesting but commercially underwhelming film The Conversation, and Friedkin departed before making a film. In the end, Paper Moon was by far the transitory company’s biggest hit.

Of course, there is more to Bogdanovich’s story than the triumphant narrative sketched here so far: films that didn’t go over with the public, films that were recut by studios, and even films that never found their way to the screen. In his book of interviews with directors, Who the Devil Made It, Bogdanovich quotes Josef von Sternberg on the subject of careers that start off smashingly but don’t proceed as planned: “Yes, but there were a few pages after that.”26 And so there were for Bogdanovich.

Peter Bogdanovich directing Cybill Shepherd in The Last Picture Show. Courtesy Jerry Ohlinger’s Movie Material Store.

But it was not only his career—fabled and fascinating as it was—that intrigued me. My mother, a movie buff, first told me about him, but she was aware of him mostly for his personal life, having followed his relationship with Cybill Shepherd—front and center in the media in the 1970s—which hastened the end of his marriage to Polly Platt. In fact, after I had seen The Last Picture Show, my mother proudly informed me that she had purchased the very issue of Glamour magazine in which Bogdanovich had reportedly first seen Shepherd’s likeness. He was stumped about who to cast in the role of Jacy Farrow in The Last Picture Show and then he saw … well, the rest is history.

For my mother and eventually for me, the man who went on to live with the Glamour girl in a beautifully appointed house nestled in Bel Air was inseparable from the man who made the movies. When I was a teenager, I was a fan of many American films made in the 1970s—that was why my mother suggested I see Peter Bogdanovich’s—but few of their directors had lives I actually wanted to live. Sure, I liked The Last Detail, but I could scarcely comprehend Hal Ashby’s counterculture lifestyle. And I loved Close Encounters of the Third Kind, but I could not really connect with Steven Spielberg’s nerdy obsession with film technology.

It was different with Peter Bogdanovich, whose life—especially up to the point we have reached so far, the release of Paper Moon—seemed both conventional enough to relate to and opulent enough to aspire to. Coming of age in Manhattan, he benefitted from his not-wealthy parents’ willingness to scrimp and save in order to send him to the pricey Collegiate School and “a snazzy boys’ camp,” as he once put it,27 as well as from their backing when it came to his artistic interests. In Who the Devil Made It, he wrote of the things he was taken to as a boy, including operas at the Met, shows on- and off-Broadway, and silent movies at the Museum of Modern Art.28 The last item on the list is most crucial, but not for the obvious reason. Because many of the movies he and his father took in at the museum were silent, he explained, “seeing these pictures gave me also a better connection to, and understanding of, my father’s past.” He continued, “Which is why the young people’s rejection of old movies … is also a rejection of family values and respect for age.”29

Well, would any of his peers harp on the need for family values or bemoan a lack of respect for age? Doubtful. By contrast, it seemed to me, Peter Bogdanovich was cut from a different, more clean-living cloth—in spite of his transgressions. Yes, his marriage to Polly Platt was wrecked in the wake of his affair with Cybill Shepherd, but those facts alone don’t tell the tale. His diaries from the mid- and late 1960s evince overwhelming tenderness for his wife, unconditional love for their two young children, Antonia and Alexandra, as well as surprising comfort with the pleasures of domesticity. That he was nuts about Shepherd threw a monkey wrench into what had been, to that point, an admirably conducted life, but it is a feeling comprehensible to anyone who has been swept off his or her feet. As Judy says in What’s Up, Doc?, “Listen, you can’t fight a tidal wave.” Decades later, Bogdanovich struck a more sober tone: “I’d been a faithful husband for nine years, but I now felt powerless to stop the momentum.” To put it another way, there were good times to be had with Shepherd, but they came at a cost. “I know my daughters have suffered,” he added, “and I have tried to make up for it ever since.”30

At least he looked back on the romance (and its fallout) with appropriately mixed emotions—and, besides, what is one divorce in Hollywood? My admiration for him was undiminished. For the most part, in the 1970s Peter Bogdanovich was having a grand time the old-fashioned way. His services were required to fashion a montage in tribute to Charlie Chaplin at the Academy Awards in 1972. He got a call to host The Tonight Show when Johnny Carson was away. He concocted a musical inspired by a book of Cole Porter lyrics that Cybill Shepherd happened to give him one Christmas. In Easy Riders, Raging Bulls, Peter Biskind paints the following picture of Peter Bogdanovich in this period: “He had become a bit of a dandy, wearing candy-striped shirts with white collars, occasionally improved by an ascot. He sported a gold signet ring with his initials on it. He relished invitations to the White House, didn’t mind a bit that it was Nixon who was doing the inviting.”31 If Biskind is trying to be sarcastic in this passage, he fails, at least as far as I am concerned. (He also gets one detail wrong: Bogdanovich wears a bandana, not—as widely reported—an ascot.) I don’t know about you, but all of this sounded pretty good to me, including the visit to the Nixon White House. What is so bad about that? I thought. My parents voted for Nixon in ’72.

Politics? Not for him. In fact, he chastised those “politically minded” stars who declined to attend the American Film Institute’s tribute to John Ford due to Nixon’s presence there. “Jane Fonda, I believe, even picketed,” he wrote a few years later. “But then, that was her main occupation those days, as well as her privilege, though one might wish she would stop mixing politics with art quite so ferociously.”32 He thus shared the dismissive attitude toward youthful protest that Judy expresses in What’s Up, Doc? After learning that Judy has been kicked out of college for blowing up a classroom, Howard asks, with a hint of concern, “Political activism?” “No,” she corrects him. “Chemistry major.”

In his documentary Directed by John Ford, there is a justly famous sequence in which Bogdanovich is heard firing questions at the director of Stagecoach and The Searchers, who is posed in front of a vista in Monument Valley but is in no mood to answer. I always loved one question in particular: “Would you agree that the point of Fort Apache,” he asks, “was that the tradition of the army was more important than one individual?” Well, as both Bogdanovich and Ford knew, there is more than this to Fort Apache, but still … even to ask such a question is so wonderfully out of touch with the zeitgeist of the early 1970s! “The tradition of the army”—what a phrase!

Better still are Bogdanovich’s on-screen conversations with Ford’s frequent collaborators, John Wayne, Jimmy Stewart, and Henry Fonda. Their thoughts are, of course, wonderfully insightful, but equally instructive are the glimpses we get of a youthful, dark-haired Bogdanovich, seen in over-the-shoulder shots at the edge of the frame before the camera moves in on the interview subjects—the slow dolly in being one of his signature visual tropes here and throughout his work. As Wayne tells an anecdote or Stewart cracks a joke, we see Bogdanovich chuckle, as if to confirm how close he is—how sympathetic, how understanding—to these men, each of whom is old enough to be his father.

Peter Bogdanovich shows Ryan O’Neal how it’s done on the set of What’s Up, Doc? Courtesy Jerry Ohlinger’s Movie Material Store.

Wrote journalist Tad Friend in a New Yorker profile of Bogdanovich in 2002: “His films transported audiences to a time before drugs, race riots, and polyester pants—a time when you drove your jalopy with high hopes to the spring dance.”33 It is right to emphasize his films’ nostalgic disposition, which comes across in offhand, incidental details such as the radios playing Hank Williams’s song “Kaw-Liga” in The Last Picture Show and the copies of the Saturday Evening Post hovered over by characters in Nickelodeon. But he was no tortured soul finding distraction from life’s miseries by making escapist fare: Peter Bogdanovich was, at this point in his life, as footloose and fancy free as his films were. As proof, consider a wonderful publicity still from What’s Up, Doc?: on one side is Bogdanovich—smartly dressed in one of those candy-striped shirts Biskind mentions—acting out a scene for Ryan O’Neal, and on the other is O’Neal imitating him precisely. Why do I suspect that Bogdanovich would have been perfectly happy if O’Neal had called it a day and allowed the director himself to do the part?

The differences between Peter Bogdanovich and me were not insignificant. He had been a teenager in Manhattan in the 1950s; I was a teenager in Ohio in the 1990s and early 2000s. His father was a painter; my father was a banker. He had a younger sister; I had a younger brother. Undaunted, I followed in his footsteps as best I could. When I read in his book of interviews This Is Orson Welles that he was sixteen when he first saw Citizen Kane, I promised myself that I would see the film at the same age and preferably under similar conditions: in a musty old theater on a midweek afternoon, with the sound of raindrops gently tap-tap-tapping on the rooftop. Later, when I began interviewing him, I never asked if his first experience with Citizen Kane was anything like what I imagined it to be. What if I had it wrong? Could I stand the disappointment?

I was already fifteen and a half when I made my vow to see Citizen Kane at sixteen. I scanned the movie listings in the newspaper, hoping against hope to read that a print of Citizen Kane would be shown somewhere near where I lived. But I was fast running out of time, and when I saw that the film was going to air on the local public-television station one evening, I decided to sit down and watch. I had told my plans to my father, who wondered why I gave up on them so quickly. I said that Peter Bogdanovich would understand: it was important to see Citizen Kane as soon as humanly possible.

At some point, I learned that Bogdanovich had not actually graduated from the Collegiate School, where he had made such an impression with his column “As We See It.” “He left high school at sixteen years of age without a diploma, because of a failed algebra exam,” the author Andrew Yule writes in his biography Picture Shows: The Life and Films of Peter Bogdanovich. “At the graduation ceremony he was still duly summoned and solemnly presented with a bulky, face-saving envelope, just like the graduates. On opening it later, he found it contained a blank chunk of cardboard.”34 Well, my interest in movies outweighed my interest in homework—especially algebra—too.

In fact, history was repeating itself—as I now sought to emulate him, he had once sought to emulate others. “I just wanted to be like those people on the screen,” he said to an interviewer in 1972. “I didn’t think about their private lives or what it was like to have all that money. I just wanted to be the people. I wanted to look like Bill Holden, because I wanted to be a real American boy, and do all those wonderful things. And with a name like Bogdanovich, there wasn’t much of a chance. I wanted my name to be Jim.”35 I was a step ahead of him for a change: at least we had the same first name.

It took three tries, but we finally connected on Thanksgiving Eve in 2003. I wondered how much his assistant had actually told him about what I was doing—I had explained to her in some detail that the article I was writing would focus on his lesser-known films, but such things have a way of getting lost in translation—because he seemed pleasantly surprised when my first questions were concerned with They All Laughed, his most personal film, an ebullient look at lovers and love affairs, shot in his hometown and peopled with some of his favorite performers, including Ben Gazzara, Audrey Hepburn, John Ritter, and Dorothy Stratten. My singular focus on this film was, I confess, partly by design: I knew how highly he thought of They All Laughed and that he was rarely asked about it. Because I had studied him so intently and sought to model myself on him so closely, when I finally had a chance to talk to him, I knew how to push his buttons.

Later in our conversation, he said, responding to a comment I made about the film, “They All Laughed was my best picture.” Pause. Did he wonder if I would agree with such a statement? Without thinking about it, I said, “I think so, too”—though I instantly regretted blurting out the words so quickly. In rushing to share such an unconventional opinion, I feared appearing insincere, which I certainly was not. I adored They All Laughed—it was and remains my favorite film of his—even if I had calculated that asking him about it first, before The Last Picture Show or What’s Up, Doc? or Paper Moon, would get us off on the right foot.

I quickly turned my agreement into a question.

“So, it’s your personal favorite?” I asked, somewhat meekly.

“Oh God, yeah,” he said. “By miles.”

I moved on, upping the ante by prodding him to talk about his visual style—another topic I knew he felt passionately about, but most critics ignored. His photography is not flashy like Orson Welles’s or picture-postcard perfect like David Lean’s, but it is oh so very purposeful. If he dollies in here, he means to say, “Pay attention—what she is about to say is important”; if he cuts to a wide shot there, he means to say, “Look closely—this may be the end or the beginning of something.”

Because he is partial to deep-focus photography, the care he puts into his images is always in evidence. Everything in the frame is sharply rendered for all to see; there are no soft areas for him to ignore. A good illustration is found in Texasville, the sequel to The Last Picture Show, in which even over-the-shoulder shots are remarkably clear and distinct; in some angles, it seems as though we see every strand of hair on the back of Jeff Bridges’s head. And in Noises Off, his hilarious film version of Michael Frayn’s farce about a maladroit theatrical troupe, one striking shot begins with six or seven people standing on a stage during a rehearsal. As most of them file out onto the stage, going to their places, the camera shifts to a two-shot with the show’s beside-himself director (Michael Caine) and one of his stars (Marilu Henner) as they gossip. In a swift camera move, we are taken from a public world to a private one. To borrow what director Wes Anderson said of another shot in another of Bogdanovich’s movies: “It’s kind of stagey, but you don’t mind at all because it’s such an elegant idea.”36

After a few questions on these topics, Bogdanovich expressed his appreciation.

“Nobody ever notices things like that, Peter,” he said. “None of the critics ever write about that kind of stuff, but to me that’s all about filmmaking.”

“I haven’t read too many interviews where you’re asked about things like this, either,” I said.

“They don’t have a clue. All they can do is ask me who I was doing an homage to.”

“I don’t think I’ve asked a single question about that!”

“Thank you very much—I noticed.”

Behind each shot in a Peter Bogdanovich film is a particular perspective. He did not invent the so-called shot reverse shot—that is, a shot of a character having a look at a particular person or thing and then a shot of that particular person or thing—but he took it to the nth degree. Think of the moment in Mask in which a close-up of Rusty Dennis (Cher) is intercut every few seconds with a medium shot of her intermittent boyfriend, Gar (Sam Elliott), as he rides his motorcycle past her. Cher’s head moves as Elliott speeds by, as does the camera when showing her angle of him. As an example of montage, this scene would have been the envy of Eisenstein—or Hitchcock. In fact, it often seems as though Bogdanovich took the principle at work in Hitchcock’s Rear Window—with all of those close-ups of wheelchair-bound Jimmy Stewart intercut with wide angles of the devious doings of Raymond Burr—and applied it writ large. “Most pictures don’t have a point of view in scenes,” Bogdanovich complained. “They just have shots.”37 Not his.

One of the best examples of looking and reacting in his films is found in a scene in the film that followed Paper Moon, the underappreciated Daisy Miller. Adapted from the short novel by Henry James, the story concerns a pair of Americans whiling away their days in nineteenth-century Europe. Although Frederick Winterbourne (Barry Brown) is beguiled by Annie P. “Daisy” Miller (Cybill Shepherd)—of Schenectady, New York—he misapprehends her character: Daisy affects a flirtatious manner in order to incite jealousy in Winterbourne and thus win his hand. In the process, however, she burnishes a reputation as a heedless, careless foreigner—and thus turns off her would-be beau.

Things do not end well for either one of them, but we get a glimpse of what might have been when early in the film Daisy sings Winterbourne the song “When You and I Were Young, Maggie.” At her family’s room in a hotel in Rome, Daisy is accompanied on the piano by her Italian friend Giovanelli (Duilio Del Prete), and we see the two of them in a loosely framed two-shot as she begins to sweetly sing.

At the end of the second line in the song, Bogdanovich cuts to Winterbourne, who is sitting opposite Daisy and Giovanelli. The camera dollies in to a close-up of him. Bogdanovich holds on Winterbourne’s rapt-looking face for a long moment before returning to an angle of Daisy and Giovanelli.

As Daisy continues to sing, Bogdanovich again cuts on a line change—finally giving Daisy a close-up of her own when she sings the next lines. The slight distancing effect of the long lens indicates that we are seeing Daisy from Winterbourne’s enthralled point of view.

Up to this point, Daisy has been looking in the distance, singing to no one in particular, but on the word daisies in the song, she glances toward Winterbourne, and the heavens melt. A very tight close-up of Winterbourne confirms that his eyes and Daisy’s have met. Their largely unspoken longing for each other is elegantly evoked in this beautiful ballet of glances.

To watch an entire film made up of such carefully worked-out moments spoiled other films for me—they seemed so slovenly by comparison. When Pauline Kael compared Robert Altman’s Nashville (a great film, no doubt) to a movie orgy, she meant it as a compliment, but what is an orgy but messy and unruly—and so is Nashville. Looking at an Altman film after a Bogdanovich film is akin to opening your mouth underwater in a swimming pool: too much, too fast.

In hindsight, though, it is no mystery why Daisy Miller broke the streak that began with The Last Picture Show, accelerated with What’s Up, Doc?, and concluded with Paper Moon. Although Daisy Miller was warmly reviewed in the New York Times (critic Vincent Canby called it “something of a triumph for everyone concerned”), and decades later it was included in The New York Times Guide to the Best 1,000 Movies Ever Made,38 the film lacked the obvious commercial appeal of Bogdanovich’s earlier films. It featured a much less sympathetic group of characters, too. In fact, Winterbourne is flat-out unlikeable—a milksop who is constitutionally incapable of seizing the day. Daisy, of course, is loveliness personified, and, as played by Shepherd, she is not merely a rogue commoner from across the ocean. She has manners, curtsying primly after singing “When You and I Were Young, Maggie,” and her hesitation in blatantly pursuing Winterbourne speaks to her propriety.

At the film’s end, Daisy is taken ill and perishes, further dimming its box-office chances. Yet the story’s tragic turn inspired some of Bogdanovich’s finest filmmaking. After learning that Daisy is ailing, Winterbourne enters the lobby of her hotel. The camera stays outside, observing the action that follows through a lace curtain hanging on a door. Winterbourne is halfway up the stairs when a desk clerk rushes over to tell him the news about Daisy—well, we assume that’s what he tells him. We can’t be certain because the voices are drowned out by Verdi’s “La donna e mobile,” which is being played by an organ grinder somewhere off-camera. Shell-shocked, Winterbourne turns around and walks toward us, opening the door with the lace curtain and letting it swing quietly back into place.

Just one scene later, Winterbourne is seen standing calmly—too calmly—above Daisy’s grave. He even manages to look her intuitive younger brother (James McMurtry—son of Larry) in the eye. In fact, Bogdanovich seems more affected by the situation than Winterbourne. He grasps, as Winterbourne never will, the gravity of losing a woman like Daisy Miller. The director’s camera flees the scene, receding from the graveyard until everything grows dim in a cloud of white smoke—which could easily be mistaken for Daisy’s spirit. “I’m a classicist,” Bogdanovich told critic Rex Reed, stating the obvious. “I like well-made films with beginnings, middles and ends, in which acting and writing are important instead of camera angles.”39 He seemed to delight in needling his contemporaries for their devotion to faddish film techniques. “I’m afraid it’s largely a twentieth-century critical fashion to value originality as the main criterion of a work of art,” he wrote in the early 1970s.40

Some saw such proclamations as signs of his arrogance, but they were, in truth, merely indicators of his self-assurance. From watching the great films and studying what it was that made them great, he trained himself how to make them. “I think that Peter had so much confidence,” Louise Stratten told me, “and that he had such a knowing from a very young age of what he wanted to do and that he was so brilliant at it that he could direct things with his left hand and backwards and with his eyes shut. He could direct circles around so many people.”

That confidence—particularly in his ability to tell a story with visuals alone—led him to decline the services of film composers on all but a handful of his films: his images would sink or swim on their own. In the most literal sense of the word, there is a lot of silence in his films. Instead of a full orchestra, we hear the wind in The Last Picture Show and the hubbub of a big city in They All Laughed. The penultimate scene in Saint Jack is startlingly quiet—in the hush of a balmy Singapore night, one man follows another, and the scene’s tension is heightened a hundredfold by the absence of extraneous sound effects or ambient noise, let alone music. And perhaps the pivotal scene in The Cat’s Meow depicts two characters playing a game of charades—silently acting out their feelings for each other.

At the same time, Bogdanovich will find almost any excuse for his characters to listen to the radio or to play a record, allowing him to gracefully fudge his “no music” rule. When watching his films, you stop counting the number of times a car whizzes by and music briefly blasts from a rolled-down window. But the music is fleeting, coming and going with the car, achieving the desired effect (a musical comment on a scene without resorting to a score) ever so quickly.

He occasionally uses the same device to nonmusical ends, as in the first shot of his expertly crafted made-for-television sequel to To Sir, with Love, which no less an authority than hard-to-please New York magazine television critic John Leonard described as “a bad idea that turned into a pretty good TV movie.”41 In the opening shot of To Sir, with Love II, a taxi-cab carrying Sidney Poitier pulls up and idles in front of the camera just long enough for us to hear a snatch of a radio broadcast: “This is Peter MacIntosh for the BBC in London. The weather forecast today ….” The words fade as Poitier’s cab drives away, but the locale of the first scene in the film has been clearly and quickly established.

Then came the flops.

Referring to the films that followed Bogdanovich’s earlier trio of triumphs, critic David Thomson once wrote, “Three-in-a-row struck back,”42 and so they did in the form of Daisy Miller, At Long Last Love, and Nickelodeon. Sure, these films had their stray defenders—Daisy Miller, as noted, was admired by several important critics; At Long Last Love eventually accumulated a devoted following, including Roger Ebert and Woody Allen; and Nickelodeon did acceptable business. But what of the man who just a few years earlier had made millions laugh and cry?

Well, he was there, all right, and that was part of the problem: At Long Last Love and Nickelodeon, in particular, were the most personal projects he had yet undertaken, the former his first original screenplay since Targets and the latter his long-promised story of filmdom’s origins. They were inward-looking films, not readily accessible to the masses in the manner of their predecessors, but if some audiences yawned, that didn’t make these films any less revealing.

Set in the Manhattan of the 1930s, At Long Last Love uses the songs of Cole Porter—including “You’re the Top,” “From Alpha to Omega,” and “Find Me a Primitive Man”—to tell of the romantic dalliances of four strangers whose paths cross: an idle scion (Burt Reynolds), an heiress with a cash-flow problem (Cybill Shepherd), an Italian émigré who has come to America to make a million (Duilio Del Prete), and a brassy singer (Madeline Kahn). The film unfolds in a succession of nightclubs, country clubs, movie palaces, and palatial estates. Some of the characters are better off than others, as fortunes are made, lost, and reacquired over the course of the story, and the emphasis on the finer things in life is undeniable. The stock-market crash is treated as comic fodder, and the lower orders are represented almost exclusively by an indecorous maid (Eileen Brennan), a straight-laced butler (John Hillerman), and an acerbic doorman (M. Emmet Walsh), none of whom seems to be sweating it.

The sets and costumes—rendered in inky black-and-white by production designer Gene Allen and costume designer Bobbie Mannix, but photographed in creamy color by László Kovács—resemble a live-action version of a cartoon panel by Peter Arno of the New Yorker. For some viewers, the results were unappealing. Critic Barry Putterman, in an otherwise sympathetic account of Bogdanovich’s career in the second volume of the great auteurist survey American Directors, wrote of the film’s “extremely icy detachment”—a not uncommon view.43 Bogdanovich may have been celebrating wealth, but he did so not because he felt entitled to it, but because he hadn’t always had it. In another context, he once quoted Cary Grant about the joys of staying at a hotel with all expenses paid: “The first thing you must do,” Grant told Bogdanovich, “is kick off your shoes and let a lot of minions pick them up!” The remark, Bogdanovich wrote, spoke volumes about Grant—and, perhaps, about himself: “Only someone who had to earn this comfort through hard or intense labor would make that sort of comment.”44 Similarly, At Long Last Love conjures a world of affluence and leisure in part because its writer-director finally had a taste of such things. After years of striving, didn’t he have a right to screen out poverty and drudgery? Even the name of the film’s production company reflected Bogdanovich’s ascent: Copa de Oro (Cup of Gold), after the street in Bel Air on which his house sat.

At Long Last Love has nothing of the hurried, racing feel of Bogdanovich’s other Depression-era comedy, Paper Moon, in which the just-scraping-by characters are always on the run—an appropriate choice because, as abstract expressionist Willem de Kooning is supposed to have said, “the trouble with being poor is that it takes up all your time.” By contrast, Michael (Reynolds), Brooke (Shepherd), Johnny (Del Prete), and Kitty (Kahn) have nothing but time, and they fill it by frequenting the racetrack, driving drunk after a night of dancing, and going shopping at Lord & Taylor. The film’s extraordinarily long takes not only capture the cast’s spirited live singing and dancing in real time but also a sense of living without pressure or deadlines. Take the scene in which Michael and Kitty sing “You’re the Top” in his high-rise apartment—following the song’s prominent use in What’s Up, Doc?, it was now something of an anthem in the films of Peter Bogdanovich: the shot begins on a close-up of champagne glasses on a tray, follows Rodney as he brings the drinks into the living room—where Michael and Kitty sit, hands entwined, on a sofa—and continues as the twosome start to move, dollying in or dollying out as the choreography permits. No cut? No hurry.

Yet Bogdanovich insists that even those who have everything are in need of something more—as Brooke says, plaintively, “What’s a million dollars without love?” Although Brooke likes Michael and Kitty likes Johnny, Michael likes Kitty and Johnny likes Brooke—a state of romantic dissatisfaction beautifully evoked in “I Loved Him (but He Didn’t Love Me),” which Brooke sings about Michael and Kitty sings about Johnny during a long walk in what is supposed to be a gorgeously green Central Park.

The song repeated most often throughout the film is indeed “You’re the Top,” but the story’s actual theme is best expressed in “Friendship.” In spite of their differences, the characters come to bravely accept their unhappiness, emerging as chums at the Old 400 dance that concludes the film. There, in a magical moment, the men find themselves dancing with their ideal mate—Michael with Kitty and Johnny with Brooke—before a bandleader commands them to “change partners!” The couples oblige, the women resigning themselves to their fate. “I think she’s more lovely now than ever I see her,” Johnny tells Kitty of Brooke, who replies with a tight-lipped “Yup.” “I think she’s more beautiful now than I’ve ever seen,” Michael tells Brooke of Kitty, who replies with an even more tight-lipped “Mm-hmm.” To improve upon a line by F. Scott Fitzgerald: And so they waltz on, borne back ceaselessly… into the penthouse.

In its own way, Nickelodeon was as show-offy as At Long Last Love: in telling of the evolution of moviemaking, the story stopped in its tracks in 1915, the year of the premiere of The Birth of a Nation—because Bogdanovich himself stopped there. “Ford, Hawks, Dwan, and these other directors have already done everything, and they were all influenced by Griffith,” he told interviewers Eric Sherman and Martin Rubin in 1968. “Unless you’re some sort of primitive talent, you have to know the history of what came before to be any good.”45

In its original conception, as Bogdanovich described it to Sherman and Rubin, the project was to be set in Hollywood “from 1909 to the present” and had at its center “a Dwan-Griffith-like figure,”46 but when he finally made Nickelodeon, he had whittled down the time period to 1910 to 1915. The film, then, would chart the glory days of the silent film: its guileless beginnings up to its arrival as an art form to be reckoned with. There were solid dramatic reasons for the decision, but also personal ones: Bogdanovich would celebrate those days because they were the ones he found most useful and inspiring.

The film centers on Leo Harrigan (Ryan O’Neal), a meek attorney who—following a series of accidents and misunderstandings—is put to work for studio boss H. H. Cobb (Brian Keith). Leo starts off as a scenarist before being recruited to take over for a director on location in rural California. He is reassured by cameraman Frank Frank (John Ritter) that the job demands little: “It’s okay—any idiot can direct.”

In fact, Leo cottons to directing, but not because he thinks he is making art. Instead, the former attorney is charmed by the misfits and amateurs who make up his cast and crew, including Frank, leading man Buck Greenway (Burt Reynolds), leading lady Marty (Stella Stevens), and juvenile script doctor Alice (Tatum O’Neal). And he is positively smitten with Kathleen Cooke (Jane Hitchcock), an aspiring actress who is the gang’s newest initiate. A romance develops between Leo and Kathleen—later becoming a love triangle involving Leo, Buck, and Kathleen—that has a simplicity and sweetness echoing the best of silent cinema.

In fact, Leo and Kathleen’s first meeting is a sentimentalized version of the meet cute in What’s Up, Doc? Again, Ryan O’Neal finds himself hounded by a persistent woman. The difference? Where Barbra Streisand is bossy, Jane Hitchcock is bewitching. In the scene, Leo is about to step off a trolley car, in which he has just concluded what amounts to his first story conference with Cobb, when Kathleen steps aboard and stumbles. Leo, having dropped the contents of his suitcase inside the car, does not see Kathleen on the floor, although she spots him. Kathleen, we learn momentarily, is “blind as a rat,” so her point-of-view shot of Leo (seen gathering up his things in a hurry) is appropriately fuzzy. Leo rushes past Kathleen, tuning out her repeated cries of “I beg your pardon” until after he has gotten off the car. She rushes to a window and asks if he is all right. Leo, mumbling to himself, stops in midstride. Kathleen asks, “What?” Leo says, “Lollapalooza”—Cobb had earlier asked that Leo’s story be “a real lollapalooza”—and then, “Hello.” The two speak for several moments until the car begins to pull away, the camera irising-out on Jane Hitchcock’s face as it grows tinier and tinier. This time, Ryan O’Neal wants—rather than flees from—the girl.

For much of its duration, Nickelodeon is an appealing episodic comedy, recounting the haphazard means by which movies used to be made (e.g., story lines were tailored to what material was shot rather than the other way around) and the equally unplanned ways in which they were exhibited (e.g., a movie’s reels were shown out of order and in combination with those from other movies). Many of the incidents are modeled on tales relayed to Bogdanovich by such directors as Allan Dwan, Leo McCarey (for whom Leo Harrigan is named), and Raoul Walsh. But the film ends up achieving a certain heft as it steadily builds toward one of the great scenes in Bogdanovich’s filmography: the premiere on February 8, 1915, of D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation, the artistry and scope of which leaves Leo simultaneously inspired and depressed. He is inspired because he recognizes the significance and power of The Birth of a Nation and depressed because he also knows that his middling one- and two-reelers do not deserve to be mentioned in the same breath.

In excerpting passages of The Birth of a Nation in Nickelodeon, Bogdanovich chose not to focus on the earlier film’s virulent racism. Instead, he shows clips of its rousing battle scene and, in an impressive director’s cut of Nickelodeon that also shifted the film from color to black-and-white, the indisputably great scene in which the Little Colonel (Henry B. Walthall) arrives home and is met by his sister (Mae Marsh) on their front porch. The relatives’ delight at seeing each other turns somber when each actor gazes sadly into the distance. With its bittersweet tone—not to mention its moments of characters looking at and away from each other—this is a most Bogdanovichesque of scenes, even though it was directed by D. W. Griffith.

When The Birth of a Nation ends in Nickelodeon, Griffith takes the stage, and Leo—like everyone else—applauds enthusiastically. Yet as he rides home from the premiere, it is not his newfound artistic aspirations but his nostalgia for the camaraderie of making movies that convinces him to persist in his crazy trade.

Riding with Leo is the old troupe: Buck, Kathleen, and Frank, along with little Alice, who is driving. Most had gone their separate ways until being reunited for the premiere of Griffith’s epic. “Might as well quit. Best damn picture that’s ever going to be made has already been made,” Leo says, referring to The Birth of a Nation. “I’m sick of this racket anyway. Get up at dawn, work all day, every night, six days a week.”