Читать книгу Amaze Your Friends - Peter Doyle - Страница 7

ОглавлениеChapter 2

I spent the next morning brooding over the events of the previous day. Whichever way I looked at it, there was no avoiding the conclusion that word had got out that Chief Superintendent Ray Waters was dead and that I was involved. A month before, quite suddenly, I’d started copping speeding tickets when I went driving, parking fines whenever I stopped. Twice I’d come out in the morning to find my tyres deflated. I’d been putting it down to coincidence, but with that anonymous phone call it was time to take action.

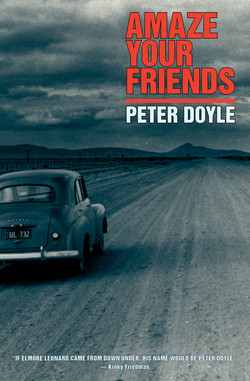

First off, I drove my beloved green and white Customline up to the car yard in Paddo and swapped it for a grey Holden, got two hundred quid cash back, smashed headlights notwithstanding. I took it straight out to the Motor Registry at Roseberry and told the kid behind the counter that I’d misplaced my licence and needed a duplicate. He gave me a form to fill in. I wrote down a phony name and address and handed it to him. He came back a while later, said they couldn’t find my records. I huffed and puffed and they gave me a stat dec to fill out, which I did, and they issued a licence to me under the name I’d given them. Then I registered the car under the new name. It was that easy.

I went back to the Kia Ora flats, paid up a month’s rent, then went straight out to find somewhere else to live. I took a lease on the first place I looked at, a flat in Farrell Avenue in East Sydney, behind William Street. It was pretty scungy and smelled of damp, but it was cheap and private and would do me well enough while I waited for the police business to die down. I moved in the same day. I left the phone connected at the old place and got it put on under the phony name at the new joint.

I spent the next day putting things in order. With my record player set up, my framed picture of Rising Fast winning the 1954 Melbourne Cup on the wall, some bottles of beer in the fridge and tea and biscuits in the kitchen cupboard, the flat didn’t seem so bad. It had its own private stairs down the back of the building which led onto a laneway that could have come straight out of a gangster movie. The landlord was a Maltese bloke named Sam. He seemed inclined to mind his own business.

After lunch I opened a bottle of beer and drank a toast to the new pad, allowed myself a little pat on the back for my quick action. I finished the beer, dropped a couple of pills, and presently paddled my board onto that familiar wave of confidence and well-being.

I went into the bathroom, and while I brushed my teeth I took a long hard look at myself in the mirror. My hair was still sandy and most of it was still there, and so too were my teeth. Sure, I could have done with a couple more pounds, and maybe my face was rather drawn. For a 31-yearold, my eyes were a little more bloodshot than they might have been, but what the hell? I ran a comb through my hair and stood up to my full height, five ten. I shaped up, threw a few punches at the bloke in the mirror. I skipped around a bit, dodging behind my guard. That’s the way, I thought, still every inch a champ.

Suitably geed up, I turned my attention to monetary matters. I got out my financial records-an old exercise book-to establish where I stood. It had been a big twelve months, starting with me well ahead, holding the combined take from the J. Farren Price robbery and my share of Lee Gordon’s Little Richard tour. But since then I’d shouted a lot of drinks, fattened up a few bookies, and shelled out some hefty unsecured loans. Now the bank balance was looking decidedly crook. The way it was going, if I didn’t get some real cash flow soon I’d be on the bones of my arse by Christmas.

But I still had a few hundred quid left and there was a chance I could call in at least some of the money I was owed. This ranged from the five quid Lachie owed me for the reefers (which I’d never get) all the way up to up to a £1200 advance that I’d made to Jack Davey six months ago. Retrieving that one would require a careful approach. Despite his being the highest paid entertainer in the country, getting money out of Davey was harder work than brickies’ labouring.

My philosophy on money had always been wait and see what turns up, but while you’re waiting, do whatever’s necessary. The more I thought about it, the more certain I was that the best course open to me was legitimacy, or the appearance of same. The problem was, short of getting an actual job, I had absolutely no idea how to earn a legitimate quid.

The next morning I went for a run and a swim at the Domain baths, then repaired to the Rock’n’roll for a restorative midday sherry while I considered how I might create a semblance of propriety. I sat and cogitated. Nothing came to me. I had another sherry, examined some of the things I’d previously ruled out.

Which led me to Uncle Dick, the blackest sheep of the Glasheen family.

It had been a while, but I could still remember his last words to me: ‘Money won is twice as sweet as money earned—remember that, Bill.’ That was just after he’d swindled me out of a hundred quid. Three or four years later he’d written to me from Adelaide to say he’d started a business and that there might be a place for me if I was interested. I hadn’t replied to that letter and there’d been no communication between us since. He could be anywhere by now.

I put aside thoughts of lost uncles and looked at the jobs section in the newspaper. I was shocked and appalled to see how little money was to be made for forty hours’ hard yakka. I closed the paper, ordered another sherry. I wrote a letter to Dick right there at the bar and sent it straight off to his old post box at the Adelaide GPO. It couldn’t hurt, I thought.

Eight days later I received a reply.

Dear Bill

It was a very pleasant surprise to get a letter from you after so long. I’m glad to hear that you’re interested in the mail order business—after all, it’s only right that family should stick together. Of course, I’d be delighted to do anything I can, even though your late father, God rest his soul, had some reservations about me. But I know I don’t need to tell you about that.

I’ve enclosed two adverts cut from the sports pages of the Adelaide Advertiser. These ads are for my two best-selling products. As you can see, one is a cure for nicotine addiction, the other a cure for bad luck. The latter consists of a small booklet (which stresses the importance of mental outlook) and an accompanying good-luck charm, the patented Lucky Monkey’s Paw. At the moment I have a number of different products for sale. They include Stop Now! (a cure for bed-wetting), Straight Talk (a cure for stammerers), and Love Secrets for Young Marrieds (a ringing indictment of prudery and narrow-mindedness). I also offer a nerve tonic and a series of life-study photographs for artists and students of the human form.

I have long been in favour of expanding the business into Sydney and possibly Melbourne. The only thing holding me back has been a lack of suitable business partners.

With you working the Sydney end, and me the Adelaide end, we could do very well, I’m certain. And who knows, maybe you will be able to introduce some new products to the range?

There’s nothing wrong with commerce and enterprise so long as you are doing better than the other fellow. You may remember me once advising you to avoid any line of work in which you are required to join a trade union or similar association—not that I’m against the working man, heaven forbid! But the way I see it, any such occupation must by definition be strenuous, possibly dangerous, and will almost certainly be poorly recompensed. That is not for the likes of you or me (although it was for your father, God rest his soul).

Anyway, in the postal sales area, you will find that not more than a few hours’ work a day, for two or three days a week, will produce a handsome return, leaving you plenty of time for the finer things in life.

I look forward to hearing from you.

Yours Sincerely

Dick Glasheen

There were two press clippings with the letter:

That night I put through a trunk call to Uncle Dick. We had a yack about the old days. About how he used to drop by to pay his respects to my recently widowed mum and see that everything was all right. Or sometimes take my brother and me to the Easter Show or the fights, and sling us ten bob each. There were other things we didn’t talk about, like when he used to stay over at our place, supposedly sleep in the spare room. After lights out he’d tiptoe into Mum’s room, a bottle of scotch in hand, be gone before daybreak. Then there was the time he shot through suddenly and the housekeeping money went with him.

Anyway, we got the cherished memories stuff out of the way and then I hit him with some questions about the business. The Lucky Monkey’s Paw, he said, was a plastic thing he had made up at a factory in Hong Kong. The nerve tonic was a harmless concoction put together by a bloke in Melbourne. All the items were small; you could squeeze the entire stock into a couple of suitcases.

‘I’m telling you,’ he said, ‘the mail order business can be marvellous. Every week there’s a slew of money orders in the post box.’

I said, ‘But are there really that many mugs out there?’

‘We call them customers, Bill. And yes, armies of them, have no fear. Didn’t you have a Phantom ring when you were thirteen?’

‘One for each hand.’

‘I rest my case.’

‘How legal is it?’

‘Pay your taxes, don’t send any filth through the post, it’s legal enough.’

‘What’s in it for you? I mean, to be frank, you’re being much more co-operative than I expected,’ I said.

‘Blood’s thicker than water.’

‘With the greatest respect, Dick—’

‘Let me finish. Blood’s thicker than water and therefore a good basis for a business relationship. This is what you do: you get some stock produced, sell it in Sydney. You pay all your own expenses and keep whatever you can make. In return you pay me a royalty for use of the idea, say ten percent of your gross sales. Twice-yearly payments would suit me. Cash, of course. And, naturally, I pay you the same for any of your ideas that I use.’

‘All right then, I’ll think about giving it a go, for a trial period. But listen, Dick, there’s a mate of mine, he’s good at thinking up schemes and shit. How would you feel about him coming in on it?’

‘If you trust him, then so do I. What’s his name?’

‘Max Perkal.’

‘He’d be of the Jewish faith?’

‘Does that matter?’

‘Not at all. I was just going to say, your four-by-two tends to be skilled at this sort of thing. Good money managers. He could be a real asset.’

Max Perkal was a pretty fair musician, he knew loads about the entertainment game, and he’d never once rooked me, not really. But what he wasn’t one little bit of was a good money manager.

I said to Dick, ‘Yeah, a real asset.’

The following week Dick sent me an ancient battered book called The Business of Life, by T. Whitney Ulmer. According to the cover it was a book of original mottoes, epigrams, oracles, orphic sayings and preachments for Men of Enterprise and Seekers of Wisdom.

In his accompanying letter Dick said:

Have a good look at this almanac, Bill. It has been my constant companion and adviser in business and all other areas of my life. It is the key to knowledge and financial success. It has helped immeasurably in attaining clarity of thought and prudence in action, and it may even help you make your fortune.

The way to use it is this: whenever you are facing a dilemma, are confused, unsure or otherwise at a loss, you hold the problem in your mind, close your eyes and open the book at random, and then read the preachment or motto. I cannot tell you how or why it works, but it usually comes up with an answer which is uncannily pertinent to the problem.’

I put the letter down and opened the book. It matters not whether the cat is black or white, as long as it catches mice, I read.

Max didn’t take much convincing to come on board. The dance game was running dead but his cabaret show was firing, especially since he’d added the sultry exotic dancer Lovely Lani to the act. He was on a winning run, so he thought, and the time was right for expanding his enterprises.

We got together, reviewed Dick’s merchandise and then decided to kick off trading with Dick’s plastic monkeys’ paws and the smoking cure. I ordered a dozen boxes of monkeys’ paws from the factory in Hong Kong, and Max had a local printer run up two thousand copies of the smoking cure booklet.

But then Max’s scheming mind really got to work, and at the end of two weeks we had a whole range of mail order items either ready to sell or in production. These included a betting system and two different courses in guitar and piano accordion. We had adverts made up, all ready to go except for a postal address. For Trotguide we had this:

And this one for the back page of the Classics Comics:

And another for Man magazine:

Max had dummied up the guitar and accordion courses from his own collection of tutors, sheet music and old song books. The betting system was something he and a pal of his, Neville, had worked out years before. It had never been known to turn a quid for anyone, but nor had anyone lost too badly with it either. Neville was now a fast-rising Labor barrister, and happy to hand full ownership of the betting system over to Max. In fact, he was insistent he receive no money of any kind from the sale of the system and that his name not be linked with it, nor with any aspect of our enterprise. It’s nice when your friends have faith in you, I told Max.

For our temporary office and storeroom, we had been using the downstairs flat at Perkal Towers, as Max’s block of flats at Bondi Junction was known, but in our third week of business Lovely Lani arrived at his door in tears and announced that she needed somewhere to live. The previous weekend her parents, Greeks, had caught her act, the Tahitian Fire Dance, at the Maroubra Junction Hotel, and now her persona was extremely non grata in the strict orthodox household. So Max, ever the gent, invited her to move into the downstairs flat for a special mate’s-rate rental. Max said we could rent a good room in the city for less than he could pull on the flat.

I checked out city real estate. I’d prefer a room with a view, I told the agent, nothing fancy, maybe Macquarie Street facing the botanical gardens. I spent an afternoon inspecting stately old buildings occupied by accountants, barristers, gynaecologists, and the like. After seeing several horribly expensive such premises, I went back to the real estate office and asked the agent, who could afford to pay rents like that? He said plenty of people. He looked at his watch, asked me did I want to think about it for a while, as he had things to attend to. I told him, listen, there must be something cheaper.

Well, he said, there was a room, downtown. It might better suit my budget, so long as I didn’t mind sharing the premises with chows and lurk merchants. If I wanted to have a look, the place was called the Manning Building. I could get the key from the tenant next door to the empty office, one Murray Liddicoat.

It was a run-down, four-storey building in the Haymarket, backing on to the Capitol Theatre. At street level there were two Chinese restaurants, a disposal store, a shoe shop and a milk bar. There was a laneway out the back where some shifty-looking Chinese blokes were hanging about.

I took the stairs to the first floor, strolled along the corridor past a rag-trade workshop, a supplier of artificial limbs, an elocution teacher, a wig maker, an ‘art studio’, and two charities I’d never heard of. A middle-aged woman walked out of one doorway marked ‘Association of Breeders of British Sheep’. She glanced my way. I said, ‘Excuse me,’ but she hurried away before I could continue.

I knocked on an unmarked door, went inside. There was an old bloke sitting at a bench, a piano accordion in pieces in front of him. I asked where I’d find Murray Liddicoat. He said he didn’t know. I tried three more rooms, got nothing but suspicious looks. I walked slowly back along the hallway, taking in the atmosphere of malpractice and dubious enterprise. It wasn’t Macquarie Street, but I had to admit, it was my kind of place.

I went into the sweatshop, Conni Conn Fashions. A good-looking girl with long straight brown hair was sitting at the front desk. She was reading a paperback, smoking a black cigarette. I said hello.

She slowly turned to face me. Her eyes were brown and bright, despite her serious expression. She was done up in the style that the Sunday papers were calling beatnik—black sweater, black stockings, not much makeup, eyes half-closed.

I asked her if she knew of anyone named Liddicoat on this floor.

She said she didn’t and turned back to her book. ‘What are you reading?’ I said.

She held up the cover of her book, Women in Love by D. H. Lawrence.

‘Good yarn?’

She said it was fabulous and returned to it.

I found Murray Liddicoat in the office two doors along. The sign on his door said ‘Private Inquiry Agent’. I knocked and went in. A large, genial-looking bloke was sitting behind the desk in an almost bare room.

He sat back in his chair, his coat open over a large paunch. ‘Yes?’

‘I have an inquiry. The real-estate bloke said you have the key to a room for rent somewhere in the building.’

‘Oh yes, I do, old son. The key’s here somewhere.’ He spoke out the side of his mouth, like he’d spent a lifetime at racetracks and boxing stadiums. His accent was broad but crisp. He rifled through his desk. ‘Ah, here it is.’ He stood up. ‘Come, I will shew thee great and mighty things which thou knowest not.’

‘Eh?’

‘This way.’

I followed him into the corridor and along to the next office. He unlocked the door, swung it open and said, ‘This is it.’

A double room with big arched windows looking out at Belmore Park. The paint was peeling, and some chunks of broken moulding were lying on the floor. There was an old scratched desk in the centre of the room, large enough to use as a work bench.

‘Do you know what the rent is?’

He shook his head. ‘I pay five guineas a week but this one would be a little more, in view of the appointments. Listen, old chap, I’m a little thirsty. I’m going back to my office. When you finish here just slam the door. Join me for a snort before you go, if you like.’

I looked around. This would do. I closed up and went next door to get to know my neighbour-to-be.

We had a couple of nips of Johnny Walker together. He kept the bottle in his filing cabinet. In that regard, if no other, he was straight out of your private-eye yarn. Before I left he put the bite on me for five quid. I felt like I’d known him for years.

On my way out I stuck my head into the brown-eyed beatnik girl’s door. She was still reading her book.

‘I found Liddicoat, he’s the bloke two doors along,’ I said.

‘Oh, you mean Murray. You should have said his first name.’

‘I found him anyway. Looks like we might be neighbours soon. My name’s Bill.’

‘Enchanted, I’m sure,’ she said, and returned to her book.

Next day I signed a lease, paid a month in advance and then rented a box at the Haymarket post office. That afternoon Max and I lugged our just-printed stock down to the new premises in the boot of his car.

On the way I said, ‘What are you reading these days?’

‘All sorts of stuff. What do you mean?’

‘Like, if I was reading D.H. Lawrence, say, tell me something to go on with after that.’

‘For you?’

‘Yeah. Or anyone. A beatnik, maybe.’

‘Anything by Jack Kerouac.’

‘Yeah, right, On the Road. What else?’

Max shrugged. ‘Albert Camus, The Outsider.’

‘What’s that about?’

‘A bloke shoots some Arabs, doesn’t give a shit.’

‘Oh yeah, like Mickey Spillane?’

‘It’s French. Very deep.’

‘What else?’

‘Marquis de Sade.’

‘That’s filth, isn’t it?’

‘Yeah, but it’s French. Very deep. Why’re you asking?’

‘Just wondering. What else?’

‘Oh, I suppose Nausea, by Jean-Paul Sartre.’

‘Yeah?’

‘There’s this bloke, everything gives him the shits.’

‘Don’t tell me. It’s French and very deep. What are you reading?’

‘I just finished this thing called Malone Dies, by Samuel Beckett.’

‘Hey, that’s more like it. A story about an Irishman, eh? There’d be some good jokes in it, then?’

‘Actually, it was written in French and—’

‘So, French is the go.’

‘You could say that. Especially if they’re existentialists.’

‘You better spell that for me.’

I gave the magazines the go-ahead to run the adverts, with the new address, and sure enough the letters and postal orders started rolling in. Over the weeks I settled into a work routine. Each day I’d empty the mailbox, then go to the office and make up the relevant packages—smoking cure, guitar tutor, lucky charm, betting system—and post them off the same day.

There was nothing too difficult about any of it, except that after a while, along with the postal orders, we began getting the occasional complaint or demand for a refund. I only answered if they wrote twice, and I never refunded so much as threepence.

The stock sold pretty evenly except for the Lucky Monkey’s Paw, which proved to be a dud. There’d been a misunderstanding at the factory in Hong Kong and they’d sent me five tea chests full. At the rate they were selling, I figured we had enough to last about three centuries. So I started looking into ways of getting them moving. I got some little strips of leather, riveted them onto key-rings and carried a pocketful around with me, giving them out as a kind of gimmick. People liked them. Next I produced a deluxe version with a bottle opener as well, and took to throwing in a complimentary key-ring or bottle opener with every package I sent out. Sometimes I’d include a little thought for the day, lifted from T. W. Ulmer’s book of preachments.

The daily business took me an hour or two to complete. After that, I’d do the banking then have lunch at one of the watering holes in the Haymarket area. Murray Liddicoat would sometimes join me. A man fond of a drink, he wasn’t without talents: he could quote the good book, chapter and verse, on just about any topic and could reel off sports results at great length. As drinking company he wasn’t too bad, although it was usually up to me to pay for the drinks.

Max kept out of the day-to-day running of the business. We had agreed on a split whereby I took wages for doing the hack work, we paid the expenses and then divided the remainder equally between us. For his part, Max was supposed to be working on expanding our product range. He talked about developing a Hawaiian guitar course and a book of jokes and magic tricks, but nothing much was coming of it. Don’t worry, brother, it’s all up here, he said, pointing to his head.

New Year, 1959 rolled around. The cops hadn’t tumbled to my new address or phone number, and there’d been no more anonymous calls or undeserved traffic fines. Money was coming in at a rate that would see our set-up costs recouped before too long, and meanwhile I had something to keep me out of trouble. And it was all legal.

Yeah, I wasn’t travelling too badly at all, I thought. I’d have that Customline back soon. Maybe I’d get a Bel Air next time.