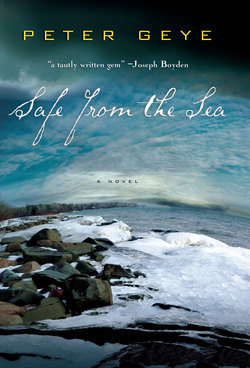

Читать книгу Safe from the Sea - Peter Geye - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

TWO

ОглавлениеThe next morning Noah woke early and headed toward the lake. The overgrown trees dripped rainwater. The giant bedrock boulders shouldering the path were covered with feathermoss and skirted with bunchberry bushes. Mushrooms and reindeer lichen grew among the duff and deadfall on the trailside.

At the lake Noah turned left and walked along the water’s edge. A hundred feet up the beach he came to the clearing in the woods, a clearing he’d all but forgotten in the many years since he’d last seen it.

When Noah turned five years old his father and grandfather built a ski jump on the top of the hill just east of the house. They cleared a landing hill on the slope that flattened at the beach. Back in Norway Noah’s Grandpa Torr had been a promising young skier. He had even competed at the Holmenkollen. When he immigrated to the States, he became a Duluth ski-club booster and helped build the jump at Chester Bowl, where Olaf himself twice won the junior championship.

Each Christmas Eve morning Noah’s grandpa and father would boot-pack the snow on the landing hill and scaffold before grooming it with garden rakes. On Christmas morning they would sidestep the landing hill with their own skis and set tracks for Noah. Olaf would stick pine boughs in the landing hill every ten feet after eighty, and by the time Noah turned nine he was jumping beyond the last of them, a hundred twenty or a hundred twenty-five feet.

Looking up at the jump he remembered the cold on his cheeks, his fingers forever numb, his toes, too, the exultation of the speed and flight. And his skis, the navy-blue Klongsbergs, their camber and their yellow bases and the bindings his grandfather mail-ordered from a friend still in Bergen. They were the first skis his father bought for him, the first not handed down. He remembered the way his sweater smelled when wet and the way it made his wrists itch in that inch of flesh between the end of his mittens and the turtleneck he wore underneath it.

But most of all he remembered the camaraderie and the lessons and the pride felt by each of them—son, father, and grandfather—in the knowledge of a lesson well learned. Even after his father had washed up on the rocks the morning after the wreck there had sometimes been a sort of reprieve from Olaf’s drunken vitriol in that isolated week between Christmas and New Year’s. Now the landing hill had grown trees again, and the bramble and deadfall made it almost indistinguishable from the rest of the hillside. Even so, at the top of the hill he could still see the scaffold and the deck standing at the side of the takeoff where his father or grandfather had stood for hours at a time, coaching and encouraging him.

“You remember this thing?” his father asked, out of breath.

Noah turned, startled, “Of course I do.”

“You can hardly see it up there.”

“I can see it.”

They were both looking at the landing hill with their hands in their pockets. The temperature was dropping, but the sky was clearing. “I used to wonder about you when it came to this thing.” Olaf gestured up at the jump. “You were a pretty good jumper, but that attention span.”

Noah smiled. “I was easily distracted.” He thought, Whatever happened to those days?

As if intercepting Noah’s thoughts, Olaf said, “Chrissakes those were fine, fine mornings.”

“They sure were.”

“You should have stuck with it.”

“I often think that. Guess I wanted to get away, out of Duluth.”

“Duluth was so bad?”

Noah shrugged.

Olaf nodded. “Maybe it wasn’t Duluth you wanted to get away from.”

“Maybe not.”

Olaf looked at him charily. “Come with me, I want to show you something.”

THE TRUCK SMELLED of cigars, and the inside of the windows dripped with condensation. The plastic upholstery covering the enormous front seat was split and cracked from corner to corner, and mustard-colored foam padding burst through the tear. A speedometer, fuel gauge, and heater control sat derelict on the dashboard, and beneath it, where a radio should have been, three wires dangled, clipped, with copper frizz flowering from each.

Noah felt like he was in an airplane, seated so high, and he marked the contrast his father’s truck cut against his own Toyota back in Boston. His car got fifty miles to the gallon. He’d have bet that the truck got less than ten. Still, he derived a definite satisfaction from sitting there in the passenger seat. He thought he’d like to drive it.

Olaf put the key in the ignition, pumped the gas pedal four or five times, and turned the key. The truck shook and grumbled but did not start. He tapped the gas pedal a couple more times and tried again. This time it groaned but finally started. He revved the accelerator, and white smoke blossomed from the tailpipe. Inside, the cab filled with the smell of old gasoline.

“Carburetor,” Olaf said, grinning. He reached under the seat and pulled out two cigars wrapped in plastic, gave one to Noah, unwrapped and bit the end off his own, and finally lit it with a kitchen match. Noah rolled his between his thumb and forefinger.

“We can take the rental car,” Noah said.

“Don’t worry about the truck.”

“I can’t believe you still drive it.”

“It’s got almost four hundred thousand miles on it.”

“That’s amazing. I lease a new car every couple years so I never have to worry about repairs. I haven’t had a car in the shop since I started leasing.”

“This thing’s never been in the shop, either.”

Olaf pulled a stiff rag from beneath his seat and wiped the condensation from his side of the windshield. He rolled his window down, too. “Crack your window, would you? Let’s get some air in here.”

Noah cranked his window down. “Where are we headed?”

“Thought it would be nice to get down to the big water.”

Olaf navigated the truck up under the low-hanging trees and onto the county road. Cool air streamed through the open windows.

“It’s getting colder,” Noah said.

“But the pressure’s rising, which means it’ll be clearing up. This wind, though, it’s going to blow the high pressure right through.”

When they reached Highway 61, Olaf turned left, away from town, and drove slowly in the middle of the road. After a few miles the lake unfolded before them. “Look at all that water,” Olaf said.

“Those waves are huge. It looks like the ocean,” Noah said. “It’s been a long time since I’ve seen this. The water was practically still yesterday.”

Olaf stared out at the lake. The deep creases around his eyes and in the slack of his chin and neck seemed flexed all the time. His lips and nose crinkled in a constant grimace, and his mouth parted as he alternated between slow breaths and puffs on his cigar. Noah watched his father’s hands, too, one on the steering wheel with quivering white-haired knuckles, the other sitting on his leg as if helping to keep the accelerator constant. He drove thirty miles per hour.

At the Cutface Creek wayside Olaf pulled into the lot and left the truck idling in one of the dozen parking spots.

After a few quiet minutes Noah asked, “How far is it from, say, Silver Bay across the lake to Marquette?”

“Well, I’d say it’s about a hundred and seventy-five miles as the gull flies. There’re eighty nautical miles—plus or minus a piece—from Silver Bay to the middle of the Keweenaw Peninsula, which makes it, what, ninety miles or so. Beyond that my best guess is another eighty or eighty-five miles, most of that across the Keweenaw, over the Huron Mountains, and only another ten or twenty nautical miles across Keweenaw Bay. Farther, of course, if you were getting there by ship. Why do you ask?”

“On my way here yesterday I picked up a radio station from Marquette. It surprised me, that’s all.”

By now they had gotten out, moved around to the front of the truck, and were leaning against the rusty bumper. Four-foot waves curled up onto the rocky shore in white explosions. They were facing the sharp wind that brought a delicate spray of lake water with it. Olaf said, “For some reason the big breakers always remind me of my mother.”

“I wish I could remember her better.”

“My mother was the single kindest person I ever knew. A saint she was. Never hit me once, never even raised her voice,” Olaf said, taking a long, satisfying puff on his cigar.

“That’s how Mom was, too.”

Olaf glared out at the water, toward a horizon resting somewhere in the middle of the lake. “My mother, she was faithful. She loved my father, God knows why. She was patient.”

Noah interpreted his father’s words as a challenge, knew that if he wanted to he could have a fight. Enough forbidden history surrounded Noah’s mother to keep him and Olaf fighting for a while. Noah pictured Phil Hember—their neighbor across the street from the old house on High Street—his mother’s lover during Noah’s high school years. There was some forbidden history. Noah resisted the temptation to bring it up. They watched the lake churning.

Olaf finally cleared his throat, spit, and stubbed out his cigar. “Solveig tells me you sell maps out in Boston.”

Caught off guard by the change in topics, Noah stammered. “That’s right. Antique maps.”

Olaf looked suspect. “Who needs an antique map?”

Noah described the maps as works of art. He told his father how he’d come to own the shop.

“What about teaching?” Olaf asked.

“I wasn’t a very happy teacher. Not a very good one, either.”

Olaf teased Noah about all those wasted semesters of college. Noah heard the good-natured timbre of the old man’s needling, so he spoke more of his own crash course in learning the business and of its strange and unexpected growth thanks to the Internet. He wondered whether his father knew what the Internet was. Noah told him about Ed, and of how the colonel reminded him of Olaf himself, of how when the mood to lecture struck him the colonel could not be stopped. Finally he said, “I have Natalie to thank. She’s the one who reviewed the prospectus and lease—she even negotiated the purchase. She’s got a mind for details I don’t have myself.”

“So how are you making it go?”

“I guess I have a mind for the maps.”

And because Olaf seemed interested, Noah elaborated. Some of the maps were three or four hundred years old and from as far away as the Horn of Africa. He described the beautiful Latin and French words he had such trouble translating, the beautiful script they were written in.

Olaf, looking even more dubious, said, “Say I wanted to buy one of these maps, what would it set me back?”

“You could spend a hundred bucks, you could spend ten or twenty thousand.”

“For an old map that couldn’t get me out the front door?”

So Noah explained again how they were less maps than collectibles, or, he repeated, works of art. Not to be used, as his father said, for getting out the front door but for admiring on the wall in your billiard room, to ogle with your country-club friends over twenty-year-old scotch.

Olaf said, “I’ll take my atlas and gazetteer.”

“When was the last time you needed an atlas?” Noah said, remembering his father’s instructions for finding the house.

“Let’s just say one won’t be necessary to find lunch. You hungry?”

OUTSIDE THE MANITOU Lodge hay bales and cornstalks and pumpkins had been set out for Halloween. There were a dozen pumpkins, all half eaten, a feast for the deer; their tracks were all over the mud. Three cars were parked in the lot, but inside, the dining room was deserted.

It was a moderately sized room with grand ambitions. The walls were paneled with dark, stained wood, and the vaulted ceiling supported four chandeliers that aspired to some kind of elegance but failed. A rippling, knotted pine floor glimmered, polished to a shoe-shine brown. Along one wall a colossal fireplace with a mantel as big as a canoe loomed over the deep hearth. Hanging over the mantel a moose head and antlers spanning four feet surveyed the room with glass eyes. On either side of the fireplace black-bear skins hung like paintings. Above the wall of windows that faced the highway, a dozen fish—chinook and brown salmon, steelhead, northern pike, walleye—hung mounted on elaborately carved and lacquered pieces of wood. The tables were sturdy and unvarnished and covered with paper place mats and lusterless silverware. The three waitresses wore black skirts and white blouses. One of them directed Olaf and Noah to a table by the window and gave them menus.

“Our soup of the day is Lake Superior chowder,” she said, filling their water glasses. She switched a peppermint from one cheek to the other and asked if they had questions.

Olaf said, “Give me the chowder. And coffee.”

Noah smiled and asked, more politely, for the same. The waitress put her pencil behind her ear, collected their menus, and walked toward the kitchen.

“Once upon a time you would have ordered a bottle of suds with your chowder,” Noah said.

“A bottle of suds? Times you’re talking about I’d have skipped the chowder altogether, ordered four boilermakers over the noon hour, and called that lunch.”

“No more boilermakers?”

“No more cigarettes, either.”

“Since when?”

Olaf ran his hand through his beard. He appeared reluctant to speak. “On the way back from your wedding I stopped in the Freighter for a pair of bourbons before finishing my drive up here. Twenty straight hours I’d been behind the wheel, thought I deserved a nip.” He paused, ran his hand through his beard again. “Met a couple of the old boys. We had a high time of it. A high time.

“The next morning I woke up in the truck. Couldn’t see a thing, the windows were all rimed from a night of snoring. I mean, they were completely fogged over. I had no idea where I was until I stepped out of the truck.” He smiled, looked almost as if a punch line were in the offing. “I was parked in front of the old house up on High Street. Hadn’t lived there in what, three years?” His smile vanished. He paused to look Noah in the eyes. “One of my bright shining moments. Enough was enough.”

“Just like that?” he said.

“Never a drop since.”

“I didn’t know people could quit drinking like that.”

Olaf merely raised his shoulder to his ear and closed his eyes for a moment. “I guess they can,” he finally said. “At least I did.”

“Do you miss it?”

“Not the booze, but I’d smoke a hundred cigarettes a day if they weren’t such hell on me.”

“What’s that?” Noah asked, pointing at an envelope on the table.

Without a word Olaf slid its contents onto the table. There were two dozen or more photographs sheathed in plastic. Olaf took one of the photos from the pile, set it down on the place mat, and wiped an imaginary layer of dust from it. He looked at Noah from over the top of his glasses—big, black-rimmed bifocals that he’d pulled from the pocket of his flannel shirt. “I guess this is what I wanted to show you.”

The waitress interrupted them with their soup. Noah thanked her.

At the same moment, as if they were one man in a mirror, they moved their soup aside. Olaf said, “Anyway.”

Noah sat dumb as his father took one and then another of the photographs from their plastic wraps. The first, a black-and-white snapshot of five men standing on the main deck of the Ragnarøk and two others suspended over the side, one in a bosun’s chair, the other on a rope ladder, looked like something out of a Life magazine pictorial. Printed on heavy Kodak paper, it had faded to sepia. Of the seven men Noah recognized three: his father, Jan Vat, and Luke Lifthrasir. They all wore scowls on their faces and looked identical in dress, wearing black wool caps, three-quarter-length peacoats unbuttoned to the waist, gray trousers cuffed at the ankle, and thick-soled black boots. The ship’s bowline was attached to a harbor cleat, sagging heavily under the weight of icicles. The ship, as the unmistakable block letters of his father’s handwriting on the back of the photograph said, was wintering up.

On the deck behind the men, the riveted hatch coamings and covers and the hatch crane were glazed with ice. The two men hanging over the side of the ship chiseled at a layer of ice. The men on deck all wore that expression so fixed in Noah’s memory—they looked caught between humor and tragedy, as though they were thinking, simultaneously, that they were elated to be home but craved leaving again, too.

In the steely background of the picture, a million shades of gray blended into the harborscape: the cone-shaped piles of taconite and limestone, the enormous cranes and rail tracks, the rail cars steaming with coal heaps. Fences, barbed wire, wooden pallets. The crisscrossing power lines and ten-story-tall grain and cement silos. A squat tug steaming through snow flurries. Ice. And, enveloping all of it, smoke from a thousand stacks and steam whistles.

Noah looked up from the picture and saw his father staring out the restaurant window. Noah thought of saying something but looked back down at the picture instead. In the background he recognized a big part of his boyhood. Driving into downtown Duluth just two days earlier he’d felt similarly transported in time. In his exhaustion he’d chalked it up to the depressive autumn mood that seemed to have settled on the city like the fog. But now, seeing the same place and thing in a different time and in different hues, he knew that he had mistaken fatigue for the nature of the city, not autumn’s coming on.

He thought back to his boyhood and the ships, his father’s ship especially—his third, actually, the storied Rag. The Superior Steel Company had a fleet of fourteen ore boats, and though there were many distinctions in their size and capacity, in their age and shape, each of the ships was distinctly superior—as they were known across the lakes—as well. Just as the Pittsburgh Steamships wore their tin or silver stacks, so the Superiors wore their black hulls and white decking. And emblazoned on the stern and port side of each ship’s nose the diamond and S.S.C. logo of the fleet looked like an opened serpent’s mouth. Though any ship from any fleet or port of call stirred something like awe in Noah—even now but especially as a boy—the ominous, serpentine Superiors ruled his imagination.

And the Rag, of course, ruled most, both in Noah’s boyish imagination and in the collective imagination of the people of Duluth. Although flagship honors fell on the newer, bigger SS Odin Asgaard, the Rag remained—until her foundering—the secret darling of the Superior Steel Company brass. Her officers’ crew all hailed from Duluth, a fact that alone would have made her revered, but she had a mystique, too, one whispered about in the sailors’ bars and church basements. Though exaggerated, an ounce of truth pervaded the legend. She was tenacious in wicked seas, as she proved over and over again in the November gales. She’d withstood ice, the shoals, the concrete piers jutting out into the lakes from Duluth to Ashtabula, and even, allegedly, a tornado in the middle of Lake Huron. She possessed the belly of a whale, too, exceeding her load limit from one trip to the next. Though the Asgaard was one hundred feet longer and made to carry three thousand tons more ore than the Rag, though the Asgaard and her type eventually replaced the ships in the Rag’s class, during the last few years of her life the Rag performed—categorically—on an almost equal annual footing with the flagship. She was the mother of the Superiors, even if not her majesty.

Noah knew all this because when the subjects of ski jumping, what was for dinner, or the goddamn unions weren’t being discussed at home, the Ragnarøk was. He knew her statistics like some kids knew the batting averages of their favorite ballplayers. He could still remember them.

Olaf’s voice seemed to whistle at him. “That’s the Rag.”

Noah looked up from the picture and saw his father’s nub pinky—the one that had been amputated at the second knuckle because of frostbite—pointing at the picture. “I know.”

“And those are the Bulldogs there, the Bulldogs and a couple hands working on the hull.” “Bulldogs” was the moniker given to the all-Duluth officer crew of the Rag in honor of their tenacity but also because it was the namesake of the local state college. “That kid in the chair is Bjorn Vifte. You knew Bjorn. Seventeen years old there. That’s me, of course, that’s Jan, that’s Joe, that’s Luke—you knew him, too—and that’s Danny Oppvaskkum, the engineer. This picture was taken a few days after Christmas the year before she went down.”

“Who’s this?” Noah asked, pointing to the kid on the ladder.

“Ed Krebs, one of the deckhands.”

“And who’s Joe?”

“Joe was second mate. Joe Schlichtenberg. He hung around when you were a kid. Joe probably froze to death. Or drowned. Danny O. was in charge of the engine room. He probably burned to death.”

Noah had always longed to hear—from his father—the story of what had happened the night the Rag went down, and even a hint of it got his pulse thrumming. “The ship here, she’s at Fraser shipyards?”

“Four or five ships from our fleet wintered up there every year. In ’66 and ’67 the Rag got her new engine, a diesel. They did it at Fraser.”

“You guys all look the same.”

“We were.”

They sat in the dining room of the Manitou Lodge for a couple hours, talking about each photograph as if it were a wonder. The pictures dated as far back as the spring of 1938, Olaf’s first year on the lakes, when he had shipped as a deckhand on the two-hundred-fifty-three-foot Harold Loki, a ship named for the original chief executive of Superior Steel. Olaf was a baby-faced kid in one of the pictures, his shirtsleeves rolled to the elbows, a cigarette dangling from his lips while a buddy’s hand stuck him with a fake jab to the ribs. Along both sides of the main deck of the ship in the background, a procession of fresh-air vents loomed like a marching band of tuba players, and the smokestack in the stern coughed up its coal smoke in pitch-black plumes.

Olaf couldn’t remember the other deckhand’s name, but he told Noah about a whole crew’s worth of sixteen-and eighteen-year-old kids shipping out in order to avoid abusive fathers or college. Some of the boys, he said, were just cut from the lonely cloth and wanted to get lost. He told him about Tony Ragu, a kid from Muskegon who worked on the Loki for the first three months of the shipping season that year before being picked up by the Duluth Lumberjacks, a minor league baseball team that wanted his ninety-five-mile-per-hour fast-ball. He remembered Cliff Gornick, a Chicago guy who put himself through Northwestern Law School by working Superior Steel boats in the summer and who eventually became a famous Chicago newscaster. Russ Jackson was the first black guy he saw on the boats, second cook on the Loki. A potbellied, middle-aged man with a receding hairline and a wife and seven kids in Detroit, he cooked the best beef brisket north of New Orleans. Olaf smiled when he talked about the Cejka brothers—one of whose sons was later a watchman on the Rag—thick-shouldered shovelers who worked in the engine room of the Loki moving coal. If not for the whites of their eyes and their ungloved white hands, Noah might not have known there were any people in the picture at all.

There were pictures of the aerial bridge at the entrance to Duluth harbor, cloaked in fog, a cat’s cradle of steel; of the Loki, the Valkyrie—his father’s second ship—and the Rag all scuttling through the locks at Sault Sainte Marie; of the Mackinac bridge spanning the straits between Lakes Huron and Michigan; of the loading and unloading complexes in Gary and Conneaut; of crewmates, some anonymous or forgotten, others so well remembered it seemed as if Olaf expected them to walk into the dining room any minute and join them; and of Olaf, standing in front of the offices of Superior Steel in the LaCroix Building on East Second Street in downtown Duluth, an ear-to-ear grin on his twenty-eight-year-old face the afternoon he passed his Coast Guard exam to become an officer, and standing behind the wheel in the pilothouse of the Valkyrie.

Noah looked up and down between the pictures and his father, and what struck him was how much he himself resembled the man in the photographs and how little the man sitting across from him now did. Three days ago he might have overlooked his father in a crowd, now he felt like he was him. Noah wondered, as his father reconstructed more than thirty years of his life with the help of the photographs, how it had felt to be him then, in the spring of 1938, and how it felt to be him now, with the burden of all that had happened and all that he’d suffered, suffering who knew what illness. More than anything Noah wondered what it would be like to sit across the table from a son, imagined a whole lifetime of moments like this: spooning baby food, helping with homework, explaining the birds and the bees, sharing a beer over a cribbage board.

By the time the waitress announced that the dining room was closing for the afternoon, they’d finished with the photographs and had been sitting in a reverential silence. “Listen, Dad,” Noah said, “why don’t you pack these up? I have to call Nat before we head back to the house.”

Olaf said, “Sure, sure.” And with the care of a surgeon, he placed each of the photographs back into their sheaths and then into the manila envelope.

“WE’LL BE OUT of your hair in a minute,” he assured the waitress behind the cash register at the Manitou Lodge. She nodded and turned her attention back to painting her nails as Noah dialed the pay phone.

“Hey,” he said, “I didn’t think I’d catch you.” The phone at Natalie’s office had rung five times before she’d picked up.

“I was starting to think you’d forgotten me. I left messages on your cell.”

“I don’t have cell reception up here. Sorry. I was going to call last night.”

“It doesn’t matter. I worked late last night anyway. New clients.” She was a management consultant and never discussed clients by name. The late nights were a job hazard. “How’s your father? How’s everything going?”

Noah looked out the window at the galloping lake, he glanced at his father. “It’s hard to say. We went fishing yesterday,” he said as though it were the strangest thing. He paused. “What about you?”

Her voice turned grave. “Now that you’re in the middle of the woods, I’m finally going to ovulate again. Of course.”

He could hear her crying and felt an impulse to hang up the phone, not because he didn’t want to hear what she said but because he knew that whatever he replied would be monumentally wrong.

“Okay,” he began cautiously. “I know the timing is terrible, I know it stinks, and I wish I were there—”

“But you’re not,” she interrupted. “I thought this would be the month. I wish you were here.”

“I know, me, too. But we might have to wait until next time.”

“What if there isn’t a next time?”

A next time. Since their most recent failure, an ectopic pregnancy that had taken Natalie months to recover from, she had come to suspect that the reason things weren’t working—the reason their efforts had yielded nothing but endless fretting, thousands of dollars in fertility-clinic bills, and a terminal attitude—was that they hadn’t been doing everything together. “You go to the clinic at eight in the morning to drop off your sperm, and I go at noon to be inseminated between a tuna-fish sandwich and a conference call—I mean, how could we expect anything? It’s just unnatural,” she had said, ignoring the fact that their course of action couldn’t be anything but unnatural. So they’d decided they would make their clinic visits together, sure that the next time things would be different. The next time was now.

He tried again. “I know this hasn’t been easy.”

“Hasn’t been easy? Noah, they had an easier time putting a man on the moon than they’ve had getting me pregnant. Keeping me pregnant anyway.” She blew her nose. “Maybe you could overnight it.”

He could practically see her, sitting behind her desk at work, looking out the fourteenth-story window. The tears, he’d not often seen them for any other reason.

“There’s an OB/GYN at St. Mary’s hospital in Duluth. You’d have to go down there, but I bet we could make arrangements. They could still inseminate me tomorrow.”

Inseminate, the sort of word that had become stock in the parlance of their infertility. All the words—prescription, ovulation, suppository, uterus, fallopian, cervix, endometriosis, laparoscopy, motility—made the whole thing feel like a science project.

“I’m sure I could make an appointment.”

“So we could overnight it? Nat, honest to God.”

“What?”

“Let’s be reasonable.”

“Injecting myself with a syringe full of fertility drugs every night is reasonable?”

“Is it the end of the world if we have to wait another month?”

“What if you’re there for three months, what happens then?”

This startled him, and he looked across the dining room at his father, whose chin was on his chest. He must have been sleeping. “I’m not going to be here for three months. Listen, I just got here. I can’t very well leave tomorrow. My father needs me right now. He’s not well, remember?” Across the dining room Olaf twitched, his head bobbed up, and he looked around the restaurant, confused. “He can hardly get his feet off the ground.”

“What’s wrong with him? Where is he now?”

“He’s sitting across the dinning room here at the lodge.”

“You’re out to lunch? You went fishing?”

“It’s hard to explain.”

“I’ve made a list,” she continued, the tone of her voice suddenly businesslike, “trips to the doctor’s office for fertility-or pregnancy-related visits: fifty-two. Number of prescriptions filled for fertility-or pregnancy-related drugs: no fewer than thirty. Number of injections: roughly two hundred. Cumulative full days missed at work: fifteen. Number of times you’ve had to jack off over some dirty magazine in the doctor’s office: eight. Number of miscarriages: three. Number of ectopic pregnancies: one. Number of dead fetusus: five.” She paused. “Number of hours spent in paralysis, bawling my pathetic eyes out: a million. Do you get the idea, Noah? I need you to come home. If it doesn’t work this time, I can’t go through it again. This is it.”

Noah looked at his father. He squeezed his eyes shut and pictured the old man laboring up the hill from the lake.

“Are you listening to me, Noah? I have a scar on my arm from where they’ve drawn blood the last three years. I have permanent bruises on my thighs from the injections.”

“My father is dying. He lives alone in the woods. He has to drive eight miles just to use the nearest pay phone.”

“He’s dying?”

“That’s what he says.”

“What does the doctor say?”

“He won’t go to the doctor.”

“But he can go fishing?”

“I know. I said it’s hard to explain.”

“Would leaving for one day matter?” she persisted, though clearly she was less emphatic.

The truth was, he did think one day was going to matter. He thought an hour mattered now. But he didn’t say anything.

“Then I’ll come there,” she said after a moment.

“You’ll what?”

“I’ll get a flight on Friday. I’m in meetings the rest of today. I have to go.”

“You’re coming here?”

“On Friday.”

“It’s not an easy place to find,” he said.

“I’ll MapQuest it.” And before he could protest she hung up.

He stood there in stark amazement, the idea of her coming to Misquah sinking in slowly. This sort of impulsiveness was not one of her character traits—though conviction of this magnitude was—and he realized again how single-minded she had become. He tried to imagine her sitting in his father’s cabin but could not see it.

Before he went back to the table, he called his sister. When she did not answer, he hung up, realizing any news of his being at their father’s house would alarm Solveig.

AS THEY MADE the slow drive back to the house Olaf looked at Noah and said, “You always did wear it around on your sleeve.”

Noah had been studying the roadside. “What’s that?”

“Whatever’s troubling you.”

Noah turned to his father. “I hope you don’t mind more company.”

“What do you mean?”

“Natalie’s coming.”

“She is?”

Noah turned his attention back to the woods. “It’s hard to explain. It’s ridiculous, really. And embarrassing.”

“Out with it already.”

“Well, she’s ovulating.”

“Ovulating?”

“Like now’s the time she could get pregnant.”

Olaf slowed the truck, pulled over, and stopped. “She’s coming here to get pregnant.” A smile spread across his slack mouth. “You’re a lucky man.”

“We’ve been trying for years.”

“That’s one of the best parts of marriage,” Olaf said, persisting with his sailor’s wit.

Noah thought to turn the conversation but realized his father was trying to make things easier for him. It was a gesture of simple kindness. Now a smile spread across Noah’s face. “I guess you’re right about that.”