Читать книгу The Select and The Orphan - Peter Lerangis - Страница 7

Оглавление

I DO NOT hear them, but I know they are near.

The creatures. The men. They hunt me through the rocks and jungle trees.

I must move, but I cannot. I fear my ankle is broken. If I stay, they will flush me out of this hiding place. When they are through with Father, they will come for me.

I pray they spare him. It is I whom they seek.

Yesterday I was the proud son of a renowned archaeologist, a man of science. We were explorers in a strange land. We would make incredible discoveries.

Today I know the truth.

Father brought me here to find a cure for my sickness. To heal my weakened body. To fix what science cannot understand.

But today I learned that my blood has sealed my fate.

If the prophecy is true, I will die before reaching my fourteenth birthday.

If the prophecy is true, I will cause the destruction of the world.

The island drew us here. It will draw others. Like Father. People who seek the truth. It must not end like this. So I leave this account for those who follow. And I pray, more than anything, that I have time to finish.

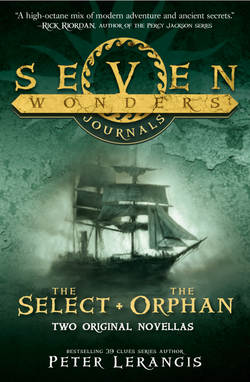

Our ship was called Enigma. She sailed ten days ago, September 14, into a red, swollen sun setting over Cardiff. But I lay in a cabin belowdecks, racked with head pain.

“Are you all right?” Father asked, peeking over for the dozenth time.

For the dozenth time I lied. “Yes.”

“Then come abovedecks. The air will be good for you.”

I followed him out of the cabin and up the ladder. Above and around us, the crew set the rigging, hauled in supplies, checked lists. English, French, Greek—their shouts kept my mind off the pain. Silently, I translated. What I didn’t know, I learned from context. I had never heard the Malay tongue, but the words floated through the air in rapid cadences. They were spoken by a powerful but diminutive deckhand named Musa.

My love of languages is not why Father hired these motley men. It was the only group he could get together in such a short time.

He knew the clock was ticking on my life.

Five weeks earlier I had collapsed during a cricket match. I thought I had been hit accidentally by a batsman. But when I awoke in a hospital, Father looked as if he had aged twenty years. He was talking to the doctor about a “mark.”

I didn’t know what he meant. But from that day, Father seemed transformed. The next two weeks he seemed like a madman—assembling a crew, scaring up funding for a sturdy ship. Impossible at such short notice! He was forced to interview vagabonds from shadows, to beg money from crooked lenders.

We sailed with a ragtag crew of paupers, criminals, and drunks. It was the best he could do.

As Father and I came abovedecks, I fought back nausea. The Enigma was a refitted whaling ship that stank of rancid blubber. Its planks creaked nastily on the water. Back at the port, Welsh dockmen mocked us in song: “Hail, Enigma, pump away! Drooping out of Cardiff Bay! Hear her as she cracks and groans! Next stop, mates, is Davy Jones!”

Our captain, a grizzled giant named Kurtz, hurled a lump of coal across the bay at them, nearly hitting one of the men. “Let me at them leek-lovin’ cowards,” he grumbled.

“Pay them no heed,” Father said.

“Not that they’re wrong, mind ye,” Kurtz said, his eyes flashing with anger. “Us heading for the middle of the ocean to find nothing.”

As he lumbered away, I looked at Father. My head pain was beginning to ease. “Why does he say this?” I asked.

Father took my arm and brought me to the wheelhouse. He took out an ancient map, marked with scribblings. In its center was a large X. Directly under that was an inscription in faded red letters, but as Father skillfully folded the map, the words were tucked away. “Kurtz sees no land under this mark, that’s why,” Father said. “But I know there is. The most important archaeological discovery I will ever make.”

“Could not we have waited and gathered a better group of men?” I asked as I glanced toward the foremast, where two Portuguese sailors were brawling with Musa. As the Malay drew a dagger to protect himself, Father ran toward them.

He did not know that I had seen the inscription he’d folded away. It was in German: Hier herrscht eine unvorstellbare Hölle.

“Here lies a most unimaginable hell.”

We reached our own Hölle early.

We were in open ocean. The sky was bright, the sails full, and the Strait of Gibraltar had long faded from sight. Eight days into the voyage, I was making progress in understanding Malay. Not to mention many of the saltier words and phrases used by these men in many other languages. I tried to help as often as I could, but the men treated me as if I were a small child. I must have seemed like one to them. My headaches were becoming more frequent, so I often went belowdecks to rest. Father would often join me for a card game or conversation.

It was during one of the games that we heard a scream above.

We raced upward. What we saw knocked us back on our heels.

The freshening sky had given way to an explosion of black clouds. They billowed toward us as if heaven itself had suddenly ruptured. Captain Kurtz was shoving sailors toward the mainsail sheets, shouting commands. First Mate Grendel, so quiet I’d thought he had no voice, was shrieking from the fo’c’sle, rousing the sailors.

The Enigma lurched upward. As it smacked back to the water, men fell to the deck. The wind sheared across the ship and the mainsail ripped down the center with a loud snap. In the thunder’s boom, I stood, paralyzed, not knowing how to help. Rain pelted me from all directions. I saw a flash of lightning, followed by an unearthly crack. The mizzenmast split in two, falling toward me like a redwood. A hand gripped my forearm and I flew through the rain, tumbling to the deck with Father. As we rolled to safety, I saw the crumpled body of a sailor pinned to the deck by a jagged splinter of the mast.

I tried to help, but my feet slipped on the planks. The ship tilted to starboard as if launched by a catapult. I was airborne, flailing. All I saw beneath me was the sea, black and bubbling. Three sailors, screaming, disappeared into the water. I thought I would be propelled after them, but my shoulder caught the top of the gunwale railing. I cried out in pain, bouncing back hard to the deck.

“Sea monster!” a voice called out. “Sea monster!” It was the sailor named Llewellyn, dangling over the hull.

I held tight to the railing. Beneath me was a horrifying groan. I took it to be the strain on the keel’s wood planking. I looked downward and saw the churn of a vast whirlpool.

In its center was a man’s arm, quickly vanishing.

Where was Father? I looked around, suddenly terrified by the thought that the arm might have been his. But with relief I saw him coming toward me, clutching the railing. “Come!” he cried out.

He grabbed my forearm. The ship was rocking. I heard a deathly cry. Llewellyn’s grip had loosened and he was dropping into the sea. I pulled away to try to grab him. “It’s too late!” Father insisted, forcing me toward the battened-down hatch.

He yanked it open, shoving me toward the ladder. Overhead I thought I heard the flapping of wings. A frightening high-pitched chitter. “What is that?” I called out.

“Must be the angels, lost in the wind! Looking out for us!” Father shouted, trying desperately to be cheerful. “Now go!”

My fingers, wet and slippery, untwined from Father’s. I fell from the ladder. Before my voice could form a cry, my head hit the deck below.

I awoke squinting.

To heat. To blaring light through the cabin porthole.

The sun!

Immediately my heart jumped with relief. The storm, the whirlpool, the devilish noises—had it all been a dream?

I called for Father, but he was by my side. I felt his hand holding mine.

“How’s the boy?” came First Mate Grendel’s voice.

I willed my eyes fully open. Father’s hair was a rat’s nest, his face bruised, his spectacles gone. His shirt had torn and now hung in strips off his shoulders. I knew in that instant that the storm had been no dream.

Father chuckled and turned to Grendel, replying, “He’s awake.”

“Aye, good,” Grendel said. “There’ll be four of us, then.”

I gripped Father’s hand. The words chilled me. “Only four of us remain?” I asked.

“I thank God,” Father said softly, “that I am holding the most important of them.”

“We’re not likely to last much longer if we can’t rig the ship to sail again,” Grendel said grimly. “And with the masts all snapped off, I don’t—”

I heard a sudden shout from above. Musa. The fourth survivor.

“Can’t understand the blasted fellow,” Grendel said. “Too much trouble for him to learn English, I suppose—”

“‘Land,’” I said.

Grendel stared at me. “Say what?”

“Musa,” I explained. “He said, ‘land.’”

Grendel raced away from us, up the ladder. Father followed, then I, on shaky legs.

Abovedecks, I nearly reeled backward from the intense daylight. Where roiling fists of blackness had smothered us, now the sun blazed in a dome of cotton-flecked blue. Musa’s face was streaked with tears, his gap-toothed smile resembling the keys of a small piano. Dancing wildly, he gestured over the port bow.

On the watery horizon was a distant frosting of yellow green.

Schwenk. Coopersmith. Martins. Vizeu. Pappalas. Roark. Llewellyn. Finney. Gennaro. Caswell …

Grendel recited the sailors’ names, placing for each a perfect seashell on a mound of sand. Reciting a prayer, he touched the white scrimshaw that hung around his neck on a leather strip: a crucifix carved into the cross section of a whale’s tooth.

The battered Enigma lay anchored out to sea, tilted to starboard. It rocked on gentle swells, its timbers groaning in ghastly rhythm to Grendel’s prayers. I felt the heat of the pink-yellow sand through the soles of my shoes. Behind us, a thick scrim of jungle greenery stretched in both directions. Animals cawed and screeched, unseen. A great mountain loomed in the distance, black and ominous, as if the storm itself had gathered to the spot and magically solidified.

Earlier we had managed to reach the shore via rowboat. All morning and into the afternoon we had traveled to and from our wounded ship, salvaging kerosene, sailcloth, wood, a small amount of salt beef and hardtack, a leather pack, a sopping wet blanket, and Father’s revolver— the only firearm that had not been submerged in seawater and damaged. Miraculously I also found this journal, relatively dry and not yet used, which I put directly into my pocket—and a pencil. Everything else had either washed away or been ruined.

I had helped Musa and Grendel build four small tent huts, then briefly explored the jungle, finding a flat stone into which I scratched my name. Father had just unloaded and cleaned the gun, and he gave me a lesson in its use. He’d been unable to find extra ammunition, so we had only five bullets for hunting and protection. Accuracy would be essential. I was skittish about shooting, but Father scoffed. “Your aim was excellent when you were spitting wadded-up papers at your schoolmates!” he reminded me.

Now, as Grendel prayed, I bowed my head. But I could not concentrate due to a prickly sensation at the nape of my neck. I had the feeling I was being watched. I turned.

A shadow slipped from the trees toward Grendel.

“Behind you!” I cried out.

The little creature was swift, a scraggily monkey with one eye missing and a wicked grin. It snatched the scrimshaw from Grendel’s neck, scooting back into the jungle with a triumphant, chattering cry.

Grendel bellowed a string of words I was not supposed to know. Grabbing the gun, he added, “I understand monkey meat’s a grand delicacy, and I’m hungry. Who’s coming with me?”

Father eyed him warily. “Can you shoot? We have too few bullets to waste on revenge.”

“Marksman, highest level in the army,” Grendel replied. “And I ain’t planning to go far. Let me bring the boy. He’ll learn something. And I’ll return him safe and happy.”

Father gave a firm no, but I reminded him I was no longer a child. That I would need to hunt, gather, and trap while we were here. I promised I would graduate from spitballs.

He softened at that, and instructed Grendel to exercise exceeding caution.

Off we went.

The jungle was oddly dark, its dense tree canopies blocking the afternoon sun. Grendel proved to be an expert tracker, using a pocketknife to carve blazes on trees. Before long we came to a glade, festooned with wildflowers. Just beyond it was a clear lagoon that bubbled fresh water. As I got closer, I saw fat golden fish swimming. They were meaty and beautiful. “We need a spear, not a gun,” I said to Grendel, looking for a stick I could sharpen.

But Grendel’s response was a forceful shove. I fell beside a thick tree. He ducked behind another. “Be invisible!” he warned.

Within moments, the bushes on the other side of the glade began to rustle. I saw a blur of brown gray and heard a snuffling, piglike sound. Then the lapping of water. I peeked around the tree. The animal’s body was blocked by the brush, but its woolly haunches were enormous.

Grendel shot. I jumped away at the sound.

A bellowing cry rang out across the lagoon like nothing I’d ever heard—deep like an elephant’s bleat, coarse like a lion’s roar. “Blast it!” Grendel cried. “Shoddy firearms! He’s getting away!”

I followed as he ran toward the lagoon. But the animal was gone. Not a sign.

Grendel stooped over a dark pool of blood and dipped his left hand into it. His fingers came up dripping.

Green.

“What the—?” With an abrupt cry, he plunged his hand into the lagoon. The water let out a sharp sizzle. His face twisted in pain, he pulled out his fingers and examined them in astonishment.

The skin was burned.

Balling his left hand into a fist, he secured the gun in his belt and pulled me away from the pool of green blood with his good hand.

What had we just seen? I shook as we walked deeper into the jungle. “It will be angry,” I pointed out.

“That beast ain’t natural,” he said. “It could kill us all if we don’t get it first.”

Grendel stomped through the brush at a rapid clip, scowling. He had stopped marking blazes now. His injured hand was wrapped in his neckerchief, but I could tell from his grimace that it still hurt badly.

Through a break in the trees, I caught a glimpse of the black mountain. It was closer now, and taller than I’d thought.

Caws and screeches echoed in the thick foliage around us. Growing louder. The animals were warning one another, alarmed by the shot and the noise of our passage. I felt as if they were surrounding us, trying to scare us off.

But within that deafening din of alarm, I could hear another sound. Not an animal noise at all but a strange buzzing melody, made by instruments that sounded as if they used neither breath nor strings. It was barely audible, yet it cut through the wild animal cries as if plucking the very sinews of my body, vibrating the folds of my brain. “Do you hear that, Grendel?” I said. “The music?”

“Them beasts ain’t music to me!” he said.

After another few minutes, though, Grendel’s rage seemed to dim. The brush was too dense, and there was no sign of the injured beast. With a few choice curses, he announced we would return to camp. As we began to backtrack, Grendel held tightly to his burned hand. He wound through the jungle, pausing every few moments as if sniffing for a trail. His ways were a mystery to me, but within moments he was pointing to one of his earlier markings on a tree. “Blaze,” he said.

We picked up speed. Glancing skyward, I noted with some alarm that the sun was low in the west. Night would be upon us soon, and I had no desire to be in this maze when darkness came.

We quickly passed the lagoon again, steering wide of the toxic blood. But at the edge, Grendel dropped unexpectedly to his knees.

On the other side of the clearing, the one-eyed monkey was jeering at us, swinging the scrimshaw like a chalice. “Me mum gave me that,” Grendel growled.

He took aim and fired. I flinched. Grendel’s aim looked to be true, but the monkey jerked aside as if it had predicted the bullet’s path. It swung up into a tree and vanished into the darkness, jabbering.

Grendel ran after the creature. I scrambled to follow, but my foot caught on a root and I tumbled into a thicket of vines. I shouted Grendel’s name.

For a moment I heard nothing. Then, from the direction where Grendel had gone, came a savage, saliva-choked animal roar.

Another shot rang out. Followed by Grendel’s scream.

I ran to the sound. Vines tangled around me like witches’ fingers but I ripped my way through.

I emerged into a small clearing. At the far edge lay the revolver on a bed of vines. A thick smear of green liquid led into the surrounding jungle.

Mixed with red.

I reached camp, hobbling and scratched by thorns. Over the water, the sun touched the horizon.

Musa had built a fire and was roasting a rather meager bird he’d snared. He hurried toward me, summoning Father from his tent. Their faces were taut with concern upon seeing me alone.

I showed him the gun, which I’d tucked into my belt. I described what had happened in the jungle.

Father took the gun and looked into the jungle. “Two bullets left,” he said. “Let’s find Grendel.”

Musa began talking angrily, hands on hips. I translated for Father. “He says it will be dark in minutes. It would be suicide to go into the trees now.”

Father looked at me oddly. His face seemed to be glowing. I could not quite read the expression. “How do you know this?” he asked. “You are good with languages, but in this short time, with no studies, no time for comparison and context …?”

I shrugged, embarrassed to have my talents praised.

“I don’t know. I suppose my skills have rather improved.”

“Indeed they have.” Father cupped his hand affectionately on my shoulder. Then, placing the gun securely in his belt, he gazed over the treetops to the black mountain. “We will set off tomorrow at sunrise.”

We found a shoe. Just one.

In the clearing by the lagoon, the pool of blood had congealed and begun to flake. It was no longer green but black.

Musa had boldly led our morning trek, following Grendel’s blazes. He was an expert at animal noises, shouting back to the birds and monkeys and keeping our spirits up. Now his face was drawn. He said he had never seen blood like this. He was worried that we had only two bullets.

I translated as he spoke, but Father’s face was faraway, lost in thought. “We’ll head for the mountain,” he said.

Musa began to protest, but Father cut him off with a wave of the hand. “I know it’s risky,” he insisted, “but with Grendel gone we are in even greater danger. A signal sent from the top of the mountain will be seen much farther out to sea.”

As I translated for Musa, Father began trekking into the jungle. Musa looked at me pleadingly. Skeptically. Continuing to the mountain meant miles through the treacherous jungle, followed by a climb that would take hours. At the top it appeared to be solid rock. We had no climbing equipment. The plan, to Musa, seemed insane.

I could not disagree. But Father was dead set, and so we trudged after him. Around us, the chattering grew louder. I began seeing jeering grins, wide eyes. A hard brown nut hurtled through the air. Ring-tailed monkeys, fossas, and lemurs—all began swinging from limbs, throwing nuts, rocks, feces. There were thirty or forty of them.

I felt something hit the back of my head and I jumped. I saw it fall to the ground: Grendel’s scrimshaw necklace. Above us, the one-eyed monkey beat his chest, screaming.

“He is returning it,” Musa said in Malay, his voice trembling. “He knows what happened to Grendel.”

The leather strap was frayed and wet with monkey saliva. Nonetheless, I tied it around my neck, to honor our fallen comrade. I felt pity for his awful fate, but fear for our own. What manner of beast had killed him—and what if it came for us?

Ahead of us, Father seemed oblivious. He knelt by a rock formation, tearing vines from its surface. “Come!” he called. “Help me, Burt!”

My fingers shook as I helped him, but soon I became lost in the wonder of our discovery. It was a pile of ancient stone tablets—dozens!—etched with intricately carved images and symbols. Winged beasts with bodies like a lion. Giant warthoglike things. Flying monkeys. A complex round design that resembled a labyrinth. The etched symbols were tiny and impossibly neat, like hieroglyphics.

Father looked ecstatic. “This is it, Burt. All my life I’ve hoped these existed, and here they are! Look at these runes—influenced by ancient Egyptian … exhibiting elements of Asian pictographs and flourishes like a crude prototype of—”

“Altaic and Cyrillic script …” I said.

“We will camp here,” he said, taking a pencil and pad from his pack.

“Here, Father?” I said, unable to control my astonishment.

“I must make copies before we continue,” he replied. “Later you can help me decode these, Burt.”

As I translated, Musa glowered in astonishment. “He expects us to go all the way up the mountain—and he wastes time with old rocks?”

I did not want to be caught in Musa’s fury. I knew that trying to change Father’s mind would be useless. But worse yet, my headache had begun to flare with renewed fury. It wasn’t just caused by the monkey chatter and Musa’s temper. No—like the distant hum of bees, the strange music had begun again. The music no one else seemed to hear: It pulsed with the jungle noises. Lights flashed behind my closed eyelids. I sat, hobbled by the pain.

Alarmed, Musa called for Father.

“Be right there,” Father replied, hunched over the tablets.

“Father, I don’t feel well …” It hurt to speak. My voice sounded high-pitched and feeble. Musa looked at me with concern.

Father mumbled something about taking a drink of water. I tried to answer him. I tried to get his attention away from his archaeology. But the music was growing louder, drowning out the monkeys, drowning out everything. Tendrils of sound pierced my brain like roots through soil.

I tried to stand up. I opened my mouth to cry out.

The last image I saw was the outstretched arms of Musa, trying to catch me as I passed out.

I gasped and awoke from a horrific nightmare. In it, I was in a place much like this cursed island, chased by all manner of beasts—giant, slavering warthogs; flying raptors.

It was a relief to see Father’s face.

Musa was building a fire at the edge of a clearing. He seemed withdrawn, angry. The sun had begun its descent into evening. The monkeys had quieted, but the music persisted in my head, as it had through my nightmare.

I struggled to sit up, my head still pounding. A thick blanket had been placed below me. I noticed that Father had piled the tablets around himself. His notebook was now filled with jottings, which he had clearly been working on while I was unconscious. He glanced at me distractedly and smiled, then looked back.

I was not expecting that. But something he’d said was stuck in my mind.

This is it, Burt. All my life I’ve hoped these existed.

It occurred to me, in a wave of revulsion, that this place had been our goal all along. We had reached the X on Father’s map. And it was indeed a “most unimaginable hell.”

Wenders the genius. Wenders the Great Discoverer. Wenders who stopped at nothing to get the great artifact.

“Is this why we are here?” I blurted out.

“Pardon?” Father said, momentarily distracted from his work.

“We rushed into a voyage without proper preparation, equipment, or personnel,” I barreled on. “We sacrificed an entire ship’s crew. Is this the price for your archaeology?”

Musa came closer, curious.

“There is a reason for this,” Father said. “A good one. You will have to trust me, Burt.”

“Trust you?” I said. “After you led us to a place your own map warned you away from? I sit here, ill with tropical fever. I don’t want to die on this island! Why couldn’t you have left me at home?”

Father turned away. When he faced me again, his eyes were rimmed with tears. “It’s not tropical fever, Burt.”

I braced my back against a tree. This was not the reaction I had expected. “Then tell me, what is it?”

“Something else,” Father replied. “It matters not, Burt. I do not want to stir fear—”

“I am already afraid!” I protested. “You raised me to be honest, Father. Can I no longer expect the same from you?”

Father replied in a halting voice, barely audible. “You have a rare disease, described in ancient texts. Those who suffer it bear an unmistakable physical marking on the back of the head. No one has survived past a very young age.”

“Is there no medicine?” I asked, my voice dry with shock.

“There is no cure for this, Burt,” Father said. “Except that which is in the texts. And as you know, there is a fine line between history and myth. The texts speak of an ancient healing power on a sacred island. Several of them corroborate the same location. And that location matches the place on the map.”

I shook my head, hoping that this was some bizarre dream. Hoping that I could shake away the monkeys and the deadly green-acid-blood creatures and the infernal music … “A sacred island? Ancient healing power? This is not science,” I said. “These are stories, Father. When I was a child you taught me the difference!”

“Power traveling through wires, glass bulbs that transmit light, conversations carried across continents—these were once stories, too,” Father replied. “The first requirement for any scientist, Burt, is an open mind.”

I wanted to protest. I wanted to translate for Musa. To have him share my outrage and confusion. But Father took me by the shoulders and gently laid me down on the blanket. “You must sleep to regain your strength. Musa and I will protect you through the night. I will explain more in the morning, and we will continue.”

I knew I could not slumber. I had to know more. I had to translate for Musa, who was tending the fire and trying to look unconcerned with our conversation.

But then my head touched the blanket, and I was fast asleep.

I woke several hours later, with a start.

Had I heard something?

I sat up. My head was no longer pounding. My body, drenched in sweat, felt cool. The illness had broken.

The jungle seemed eerily silent. Gone were the chatterings and hootings that had filled our day. Gone, too, was the buzzing, murmuring music. It was as if the night itself held its breath.

Musa’s fire had burned to coals. I could see him in the dim glow, dozing, curled up on the ground. I glanced around and made out Father’s silhouette at the opposite rim of the clearing. He was clutching his revolver, his back propped against a tree.

Snoring.

“Father!” I called out.

He muttered something, his head lolling to the other side. They were both exhausted.

For our own safety, I would have to take the night shift. As I rose, intending to take the gun from Father, I spotted a movement in the woods behind him. Not so much a solid thing as a shift of blackness.

I heard a stick snap to my right. A high-pitched “eeeee.”

Behind me, Musa let out a brief yell. I spun around.

He wasn’t where he had been. In the dim light of the coals, I saw his legs sliding into the black jungle.

I called his name, running after him. But I stopped at the edge, where the darkness began. Entering it would be a colossal mistake. I needed the gun, now. I leaped toward Father. I saw him awake with a start.

My shirt suddenly went taut, pulled from above. My feet left the ground, and I rose swiftly into the trees as if on marionette strings. The silence erupted into a chorus of earsplitting screams. I felt sharp, furry fingers closing around my arms and legs. The monkeys! They were pulling me, turning me around. I fought to free myself, but their strength was astounding. More swung toward me from the surrounding trees as if summoned—dozens of them. Below me, Father shouted in horror.

In the red light of the waning fire, I could see them exchanging palm fronds, twigs, ropelike vines. They jabbered to one another, eyes flashing, as they braided, twisted, and tied knots with speed and dexterity. Before I could understand what they were doing, they let their creation drop from the branch.

Then they pushed me over.

I screamed as I landed in the taut mesh they’d just woven. It was a carrying net, which they passed from monkey to monkey like relay racers as they swung from the branches. In jerking fits I glided over the jungle, rising higher and higher into the blackness. Father’s anguished shouts soon faded, and I could see the gibbous moon peeking through the tree canopy.

In the dim light, the black mountain loomed nearer. The little creatures were tossing me now. Cackling. Playing. I tried to tear my way through the net, but it had been twisted into an impossibly tight mesh. I swung like a pendulum, smacking into trunks and branches. The monkeys’ cries seemed to grow more excited now, rising in pitch and intensity as if in argument.

Finally I saw one monkey leap from a tree and sink its teeth into the arm of another who was holding me. The whole troupe quickly joined in, screeching and beating at one another.

They were fighting for my possession.

I curled into a ball and prayed.

The chanting came as a relief.

I had been swung and dropped, slung over shoulders, tossed like a ball. I did not know where they’d carried me, as it occurred in nearly complete darkness. Through the mesh I had seen only fur and occasional eyes and teeth.

When the net was removed, I was sitting on a smooth rock surface at the edge of a large hole. The monkeys quickly dismantled their sack, then used the vines to tie my arms behind my back. The air was quite a bit cooler here, and I could hear languid drips fall into the blackness below. Rock walls rose all around me, their crags seeming to shift and dance with the reflected flicker of candlelight.

Across the hole was a doorway into another chamber, cut into the wall. People were chanting in there, their shadows moving in the light. I heard the strange music, too.

The voices were chanting in harmony to it.

“Hello?” I called out across the hole.

My voice boomed out, echoing off the walls. I looked up into a rock ceiling high above. I was in an enclosed place, some sort of cavern. I had been so smothered by the monkeys and the net that I had no idea how I’d gotten there.

In reply, a wizened man appeared in the cave opening. His cragged face seemed to have been hewn out of the rock itself, and his wispy white hair hung down to a silken robe. A gold-filigreed sash hung over the man’s shoulder with an intricately embroidered sun symbol. Under any other circumstance, I would have complimented his wardrobe. But the one-eyed monkey sat on the sash, grinning at me sassily.

The man’s eyes rolled back into his head as he doddered toward me, and he held high a chalice so heavy that I was afraid it would break his frail arms. Behind him followed six other men, also chanting. The second carried an elaborately carved black sword on an embroidered cushion. I expected an orchestra to follow them, but their little cave appeared to be empty. The music, as always, was coming from nowhere.

And everywhere.

The old men circled the hole. The third in line had a small basket, from which the monkey pulled little stone tokens and dropped them into the hole. Each token landed with a loud, watery plop. So—a well.

“Who are you?” I pleaded, but they ignored me.

I edged away. Despite the horrific trip there, I felt oddly strong. The music, louder than ever, no longer hurt my head. In fact, for the first time in days my head did not ache at all.

As I listened to the strange guttural chant, the words seemed to arrange themselves inside my brain. Like the ingredients to a complex recipe, they flew through filters of grammar, structure, context, relationships. I was certain this was no language I’d ever heard before, but to my utter astonishment, I was beginning to understand it. Some of the words were obviously names—Qalani, Karai, Massarym—but I picked out “long-awaited visitor” … “select” … “sacrifice” … and something that sounded like the Greek letter lambda.

As they drew closer, I yanked at the bonds around my wrists. Yes. I felt a certain give. Talented as the monkeys were, they were better at weaving nets than binding wrists.