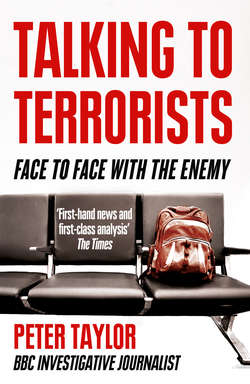

Читать книгу Talking to Terrorists: A Personal Journey from the IRA to Al Qaeda - Peter Taylor - Страница 10

ОглавлениеChapter Three

Talking to Hijack Victims

Talking to terrorists is not just about governments or their intelligence services engaging in dialogue with their enemies. Innocent citizens have found themselves in situations where they have come face to face with terrorists, in a siege or aircraft hijacking, and talked to them in the hope of securing their survival and release. They too are the victims of terrorism: the experience of staring death, and the terrorists, in the face often colours the rest of their lives. In such circumstances, talking to terrorists can be a matter of life or death. The hijacking of an Air France Airbus by four Algerian Islamist extremists on Christmas Eve 1994 provides a unique insight into the mindset of the terrorists who carried it out, and the political situation from which they emerged. It was also a prophetic event. The Berlin Wall had fallen five years earlier. The Cold War was over. Few foresaw the emergence of the new threat that was to overshadow the next two decades: Islamist extremism and the rise of political Islam. In Algeria, the conditions were ripe for both, and it is in Algeria that we first see the emergence of the phenomenon.

The hijackers of the Air France Airbus had possibly never even heard the name Al Qaeda. In 1994 Osama Bin Laden was exiled in Sudan, building his organisation and extending its global reach. Nevertheless, the hijackers did regard themselves as mujahideen, adopting the mantle of their Algerian brothers who had fought jihad against Soviet troops in the 1980s – Algeria had provided one of the largest contingents of Arab mujahideen. When the Soviet Union withdrew from Afghanistan in 1989 and many of these Algerian veterans returned home, few had any notion of global jihad. Their cause was indigenous. Jihad was primarily about local regime change. The target was the military government of the FLN – the Front de Libération Nationale.

The social and political conditions in Algeria were slow-burning incubators for revolt. By the late 1980s, 40 per cent of the population of twenty-four million were under the age of fifteen. Many were in school, being educated for jobs that didn’t exist. They became known as the hittistes, ‘those who prop up walls’. They were a potential reservoir of recruits for revolution.

France had been the colonial power in Algeria since 1830, when it invaded the impoverished North African country and scorched its earth to stamp out resistance and ensure the subjugation of the native population. In 1954 insurgents embarked upon a savage guerrilla war in which atrocities were committed by both sides, graphically illustrated in Gillo Pontecorvo’s film masterpiece The Battle of Algiers. The insurgents of the FLN were the ultimate beneficiaries, taking power when France granted Algeria her independence in 1962. But for most of the country’s impoverished people the sweetness of independence soured over the years. Growing discontent among the urban population in Algiers and elsewhere resulted in strikes and demonstrations. There was little work, no regular water supply, and food was running out.1 In the 1980s radical clerics seized the opportunity to build support for the Islamist cause through a network of neighbourhood mosques. They provided soup kitchens, food, clothing and welfare, building a political base as Sinn Féin was doing in Northern Ireland at around the same time. Political Islam began to flourish in the fertile soil provided by dire social conditions and endemic political repression.

The military government of the FLN ruthlessly put down the protests, that seemed uncannily like an Algerian intifada,2 with the army being given free rein to shoot demonstrators and torture those who had been arrested.3 The protests climaxed on 10 October 1988, when the army fired into a crowd of 20,000 people, killing fifty.4 The slaughter fuelled rather than stemmed the rise of political Islam. ‘Black October’ became Algeria’s equivalent of Northern Ireland’s Bloody Sunday or South Africa’s Soweto massacre.

The government saw the warning signs and began to ease off, legal-ising political parties to give voice to the dispossessed and discontented. By far the largest and most prominent of these was the Front Islamique du Salut (FIS – the Islamic Salvation Front), which campaigned for an Islamic state based on sharia law, the legal code derived from the Koran and the teaching and example of the prophet Mohammed. In 1991, in the hope that it would serve as a political safety valve, the government allowed multi-party elections for the first time since independence. In the first round, the FIS won such a clear victory that success in the final round seemed inevitable. The party accepted the principle of one man one vote as a means of achieving power, but once in power it would abolish democracy forever. The government cancelled the final round of the elections, probably fearing a repetition of Iran’s Islamic revolution, led by Ayatollah Khomeini, over a decade earlier.

Far from drawing the sting of the Islamist opposition, the cancellation made it even stronger. Many leaders of the FIS were arrested, and in response to the military crackdown various militant groups emerged, the most significant of which was the Groupe Islamique Armé (GIA – the Armed Islamic Group). Its core consisted of veterans of the Afghan jihad, who trained and indoctrinated young Algerians in the skills and ideology of guerrilla war. The GIA had no shortage of recruits or targets. France had become an additional enemy, as the FLN’s ally in a civil war that became a terrible showdown between the Islamists and the military government. About 200,000 people are believed to have died in the violence.5 The scene was set for the hijacking that was to be a harbinger of 9/11.

The four GIA terrorists who hijacked Air France Flight 8969 at Houari Boumediène airport in Algiers on Christmas Eve 1994 planned to crash it into the Eiffel Tower, forcing the pilots to aim for it at the point of a gun. Even if they hadn’t managed to hit the tower, which realistically was a nigh-impossible task, the plane would have crashed on the French capital, with horrendous consequences. The outrageously ambitious plan came perilously close to succeeding.

I wanted to find out what such an experience was like for the passengers and members of the crew who had lived through the nightmare and talked to the terrorists at first hand. I also wanted to speak to members of the French special forces whose mission had been to storm the plane and rescue the hostages. They weren’t in the business of talking to terrorists – just killing them.

I met some of the passengers, crew members and elite commandos at a hotel in Paris, ironically in the shadow of the still-standing Eiffel Tower, and interviewed them over two intense days. We set up the camera in a room in the bowels of the hotel, and stuck a ‘Please do not disturb. Filming in progress’ notice on the door in both English and French. We do this more in hope than in expectation that the request will be heeded, and filming had to be stopped on several occasions because of the clinking of glasses or noisy exchanges outside the room. It always seems to happen at a crucial point in an interview. Other hazards regularly encountered during filming are aircraft noise, police sirens, drilling and barking dogs. Such interviews are intense, and their intimacy is the result of establishing a relationship with the interviewee which often results in his or her forgetting that they’re being interviewed. A single interruption, however brief, from chinking glasses or barking dog, can mean that the emotional bond is broken, and it is rare to get the same response again.

The interviews in Paris over those two days were harrowing, long and exhausting. I felt for my interviewees, who gave so much of their emotions as they recalled the most terrifying three days of their lives.

* * *

The first indication that all was not well had come at 11.15 a.m. on Christmas Eve as the Airbus waited on the tarmac at Algiers, ready to take off for Paris. Four men dressed like officials came on board carrying Kalashnikov automatic rifles, and ordered the passengers to produce their passports, as they said they were carrying out routine checks. Some of the cabin crew were immediately suspicious, as Kalashnikovs weren’t normally carried by the police or customs officers. The captain, Jean-Paul Borderie, told me he feared the worst when one of them entered the cockpit: ‘He turned round for a moment and I saw something that looked like sticks of dynamite sticking out of his coat pocket. A stick of explosives! This was really weird.’ The crew’s suspicions were soon confirmed when one of the four announced who they really were over the plane’s intercom system. ‘We are the Soldiers of Mercy,’ he proclaimed. ‘Allah has selected us as his soldiers. We are here to wage war in his name.’

The hijackers were armed with guns, grenades and twenty sticks of dynamite. Their leader was twenty-five-year-old Abdallah Yahia, a petty thief and former greengrocer from one of Algiers’ most impoverished neighbourhoods, Les Eucalyptes.6 It was also an Islamist stronghold. Yahia had joined the GIA two years earlier, and had risen rapidly through its ranks. His notorious local unit was known as ‘Those who Sign with Blood’, and was responsible for the brutal murder of several foreigners, five of whom were French. Yahia demanded that the plane should take off for Paris immediately. But it was going nowhere. The Algerian authorities were determined not to give in to terrorism, and the aircraft could not move from the tarmac until the passenger steps that were attached to it were removed.

Inside the plane, Islamic law ruled. The women were ordered to cover their heads. One Algerian passenger, Zahida Kakachi, who had been looking forward to midnight Mass in Paris, objected. ‘I don’t want to wear a headscarf,’ she said. ‘I won’t wear it. It’s out of the question.’ But her cousin, who was travelling with her, entreated her to do as instructed. ‘At this point I realised that this was not the time to make a stand,’ Zahida remembered. One of the stewardesses, Claude Burgniard, also objected: ‘It was really degrading to put something on my hair because of an old-fashioned, ancestral belief. I disliked it very much, but I did it to be like the other women, to support them.’

By 2 p.m., with no sign of movement, Yahia was losing patience, and decided it was time to show that he meant business. One of the passengers, an Algerian policeman, was singled out, taken to the front of the aircraft and told to kneel down behind a curtain. The passengers and crew could not see what was happening, but they heard the policeman pleading for mercy: ‘Don’t kill me. I have a wife and child.’ A shot rang out, and his body was dumped on the tarmac. Shortly afterwards, a Vietnamese diplomat was ordered to the front of the plane, where Yahia’s second-in-command was waiting. The man, thinking he was on his way to freedom, wanted to take his bottles of wine with him but was not allowed to remove them from the overhead locker. He then asked if he could have his passport back. ‘You won’t need that where you’re going,’ he was told. He was then shot in the back of the head and thrown out onto the tarmac.

Half an hour later, with two lifeless bodies lying on the runway outside the plane, there seemed to be signs of progress. Yahia agreed to let some of the hostages leave in exchange for the release of two prominent Islamist prisoners. At 2.30 p.m. sixty-three passengers, all of them Algerian, got off the plane. But that was it. Stalemate followed. The hijackers refused to give themselves up, and the authorities refused to let the aircraft leave. The Algerians then tried another approach. At 9 p.m. they brought Yahia’s mother to the control tower to plead with her son over the radio. ‘For God’s sake, Yahia, my son, I’m afraid you will die. You’re abandoning your family, your son. Yahia,’ she cried, ‘I can’t bear the thought of you dying.’ Yahia remained unmoved. ‘No, I’m sorry. You are my mother and I love you, but I love God more than you, and we will see each other again in Paradise.’ The stalemate continued.

Despite the two brutal murders, there was still deadlock as the Algerian authorities refused to remove the passenger steps and give clearance for the plane to depart. The silence of that first long night was broken only by the sound of one of the hijackers walking up and down the aisles, reciting verses from his Koran and talking to the male passengers. ‘We are the mujahideen,’ he kept saying. ‘We have come here to die. Do you realise how lucky we are? We are going to die as mujahideen for our faith, for Allah. And can you believe it, there are seventy-two virgins waiting for us.’ None of the terrified passengers saw fit to question the certainty of his belief.

One of the cabin crew, Christophe Morin, had vivid recollections of that claustrophobic night in captivity. ‘It was hellish. The night seemed endless. The passengers were silent. It was like being trapped by a lead weight, drowning in those prayers. It was a world with no freedom, forced to listen to these endless verses.’ Zahida Kakachi remembers how still and beautiful the night outside looked. ‘There was a full moon. The ground seemed to be made of silver. There were all these white birds, and the tarmac was shimmering from the light of the moon.’ One of the hijackers noticed her looking transfixed out of the window. ‘Each of those birds will take a soul up to Paradise,’ he said. Zahida was not reassured.

On Christmas Day, the second day of the hijack, with the plane still grounded in Algiers, the French government had finally got its counter-terrorist plan in place after long deliberations involving the Interior Minister, Charles Pasqua. Members of France’s elite anti-terrorist police unit, the Groupe d’Intervention de la Gendarmerie Nationale (GIGN), had been flown to a disused military airport in Majorca to be on standby ready to storm the plane when the opportunity arose. Majorca was the closest the GIGN could get to Algeria without infringing Algerian sovereignty. The French had offered the Algerians assistance, but this had been politely refused. It would have been embarrassing and impolitic for the FLN government, that had fought the French in a bloody eight-year guerrilla war for independence, to be seen to be seeking assistance from its former colonial master. Pasqua told me that at this stage intelligence had been received from the Algerian secret service about the real purpose of the operation. ‘It was very worrying,’ he said. ‘The true aim of those terrorists was to crash the plane on Paris.’ Subsequently Metropolitan Police officers would raid a safe house in London believed to be connected with the hijackers and retrieve a propaganda pamphlet the front cover of which showed the Eiffel Tower in flames.

Christophe was convinced that he was going to die, and summoned up the courage to confront one of the hijackers and tell him that he did not want to meet his end with a shot to the back of the head: ‘Whoever my murderer turns out to be, I want him to look me straight in the eye as he kills me.’ The hijacker appears to have been surprised by the request. ‘Don’t worry,’ he said. ‘Even if you do die, you will go straight to heaven where you will find seventy-two virgins waiting for you. You will die as a martyr, so there is nothing to be afraid of. So why are you scared?’ Christophe simply replied, ‘All I know is that we seem to be on a journey that will end in death.’

By the end of Christmas Day, with the plane still on the ground, the hijackers were getting desperate. Two bodies on the tarmac, visible proof of their determination to carry out their threats, had not been enough to persuade the Algerian authorities to let the plane depart. At 9 p.m. Yahia issued an ultimatum. Unless the plane was allowed to depart by 9.30 he would start executing the hostages one by one, at half-hour intervals, until they were allowed to take off for Paris. The deadline came and went. Yahia picked out a French hostage, Yannick Beugnet, a cook from the French Embassy in Algiers who was flying home to spend Christmas with his wife and children. At gunpoint, Yahia marched him to the cockpit and forced him to address the control tower, where his words were recorded: ‘Our lives are in danger now. If you don’t do something, they are going to execute us. Something must be done as soon as possible.’ Yahia then snatched the microphone and shouted, ‘I swear we will take him and we will dump him out of that door. And we don’t give a damn about you. See how we can hit you where we want and how we want. OK, so now we are going to throw him out. The door is already open. Now just listen to how we shoot him and dump him.’ A single shot is then heard on the recording.

With three bodies now lying beneath the plane, and the prospect of another one every thirty minutes, the Algerian authorities finally decided to give in. Although they had had their own special forces (colloquially known as the ‘Ninjas’ because they dressed all in black) on standby, they had decided against using them, fearing a bloodbath. That fear was shared by many of the passengers, who had little faith in the Ninjas’ ability to carry out a rescue without massive loss of life.

At 1 a.m. on Boxing Day, the third day of the hijacking, Yahia’s demands were finally met. The passenger steps which had prevented the plane from moving were finally taken away, and Flight 8969 was cleared for take-off. No doubt to the intense relief of the Algerian government, the problem was out of their hands. Now the French could deal with it.

The plane’s destination wasn’t Paris, but Marseilles. Captain Borderie explained why: ‘You need approximately twenty tons of fuel to get to Paris, but once you’ve been stuck on the ground for a couple of days, your reserves go down. You need fuel for the air conditioning, for electricity and for the coffee machines. With two hundred people on board, it goes quickly.’ French Interior Minister Charles Pasqua was now a much happier man. Knowing what he did about the real purpose of the hijacking, he didn’t want the aircraft to go anywhere near Paris. ‘Once it landed in Marseilles to refuel, it was absolutely clear in our minds that the plane wouldn’t be going anywhere else,’ he told me. Orders were given to the GIGN on standby in Majorca to get to Marseilles as quickly as possible, and to prepare to put their intensive training into practice and storm the plane. They arrived in Marseilles just twenty minutes before the Airbus touched down at 3 o’clock on Boxing Day morning.

Yahia, determined to get to Paris to carry out the planned attack, demanded twenty-seven tons of fuel, three times the amount necessary. The airport authorities played for time while the GIGN got ready. ‘We told the terrorists we would bring them some fuel,’ said Pasqua, ‘but we explained that we had some technical problems, and didn’t have enough tankers to transport it. We told them various things to gain time.’ The negotiations carried on through the morning and much of the afternoon, with Yahia growing increasingly frustrated and menacing at the lack of progress. ‘It’s not you who decide or the pilot,’ he warned the control tower. ‘We are the ones who decide. And you will pay very dearly.’

The protracted delay was necessary while the GIGN worked out where the hostages and the hijackers were located on the plane, and what weapons and explosives the hijackers had. Valuable information was fortuitously provided by an elderly couple whom Yahia agreed to let off the plane. He had been prepared to allow them to disembark in Algiers, but they hadn’t wanted to walk over the dead bodies. They came down the steps of the plane at 4.05 p.m., and were immediately debriefed by the GIGN. They were able to give details about the number of terrorists, their weapons and the hierarchy within the group. Yahia and his number two, they said, seemed to spend most of the time in the cockpit.

The French authorities managed to protract the negotiations for a total of thirteen hours. By then Yahia had had enough. ‘This is the last chance,’ he told the control tower. ‘One hour, and then you will have to bear the full responsibility.’ If the fuel didn’t arrive by a 5 p.m. deadline, he said, they would start killing the hostages. The three dead bodies in Algiers indicated that he meant what he said. As there was no sign of movement from the airport authorities, he probably knew that the hijackers were never going to get to Paris to carry out their mission. Zahida noticed their attitudes change as they realised that martyrdom in Marseilles was the only option left to them: ‘They started to read verses from the Koran out loud, and the verses spoke of death. “We shall die. God is waiting for you. We shall die as warriors. We do not fear death.”’

With five minutes to go to the 5 p.m. deadline, Zahida was convinced that she was going to die. Most of her fellow passengers probably felt the same. No one inside the plane was aware of what was going on outside. In Algiers the Ninjas had been visible; in Marseilles, the GIGN were not. Concealed out of the line of sight of the aircraft, the assault team was now fully armed and ready to move. One of its officers, Thierry Lévêque, told me what it felt like at that critical time: ‘We know the terrorists are heavily armed and that they’re likely to use explosives, so we’re thinking that as soon as we walk in there, it’s going to be fireworks, real combat. It’s a good moment. There was emotion and fear, fear that is in your stomach before you go up and meet your adversary. Here you are playing with life and death.’ Lévêque’s colleague Roland Martin described the final moment before storming the plane. The members of the team piled one hand on top of the other in a pyramid of physical and spiritual solidarity. ‘All these hands became one single, powerful hand which had the strength to take on the terrorists. That was it.’

At 5.15 p.m. the GIGN, masked and dressed in black, raced to the plane on a motorised passenger gangway and attacked through the rear and side doors. The stewardess Claude Burgniard remembers, ‘They were not human beings. They were machines.’ There was a fierce gun battle as the terrified passengers dived for cover between and under the seats. Yahia and two of the other terrorists were shot dead while offering determined resistance. That left one, Yahia’s number two, who was also determined to go down as a martyr, with gun blazing. ‘Then we had to deal with this warrior,’ Roland Martin told me. ‘I described him as a warrior because to launch a counter-attack single-handedly against the GIGN meant that he was doing his duty.’

When the noise and smoke cleared, all four terrorists were dead. Ten members of the GIGN were wounded. Miraculously, all the hostages were alive. They had been held prisoner on the plane for fifty-four hours. Their liberation took just twenty minutes. The Eiffel Tower survived too.

There is a fascinating and instructive postscript to the story. Among the political leaders of the Islamic Salvation Front who were arrested in the wake of the cancellation of the multi-party elections was a charismatic young cleric called Ali Belhadj, who had studied at Wahhabi schoolsw in Saudi Arabia and had risen to become the organisation’s number two. He had been one of the prime movers of the demonstrations that had prompted the government to grant elections. I remember seeing remarkable video footage of a vast Islamist rally in Algiers shortly after the arrests in which Ali Belhadj’s seven-year-old son Abdelkahar, in full junior Islamic dress, addresses a vast crowd, calling for an Islamic state and the release of his father, who was serving a twelve-year sentence for armed conspiracy against the regime.7 ‘There are a billion Muslims and we don’t have a state that rules by God’s holy law,’ he shouts in the high-pitched voice of a child. ‘Isn’t that a dishonour and shame on us all?’8 The crowd roars its approval as the little boy is hoisted aloft by his father’s supporters. That powerful image brought vividly home to me the force and potential of political Islam.

We then found some even more remarkable footage that was shot many years later, in 2007. It was in a propaganda video made to launch ‘The Al Qaeda Organisation in the Islamic Maghreb’.x There, standing in the woods in combat gear and holding a Kalashnikov, was Adbelkahar Belhadj, no longer the seven-year-old hero fêted at the rally, but now a fully-grown and fully-armed Al Qaeda combatant. The cause lives on, running through the blood of families in Ireland, the Basque country, Palestine, Kashmir and other conflict zones around the world. To its adherents, setbacks like the killing of the four Algerian hijackers make it even stronger.