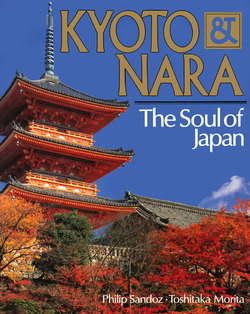

Читать книгу Kyoto & Nara The Soul of Japan - Philip Sandoz - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

Visitors to modern-day Japan tend to be either impressed or depressed, depending on their viewpoints and expectations. Arriving at an international airport in Japan is no different from arriving, say, in London, Lisbon, or Los Angeles. The Hyatts, Hiltons, and Holiday Inns could be in Miami, Manchester, or Melbourne. Walks along the main streets of Tokyo or Osaka or almost any other Japanese city turn up little different from any Western city. The eyes are filled with tall buildings, designer-brand shops, and well-dressed people; and the ears are assaulted by traffic noise, loudspeakers, and the normal cacophony of urban life anywhere in the world. All in all, those arriving in Japan expecting Zen-like tranquillity and inklings of an ancient culture could well be disappointed.

This need not be so. Stray just a little from the paved boulevards and traditional Japan rapidly reasserts itself. Narrow alleys, wooden houses, small temples and tiny shrines, statues of the major gods, goddesses, and thousands of minor deities, public bathhouses, mom and pop stores, beautifully manicured gardens the size of tea trays, paper lanterns, paper doors, paper street decorations, the call of street vendors, the gush of laughter, the scream of school children, and the shrill of insects all contribute to what Japan has always been, and what it remains today.

It is often claimed, usually by the Japanese themselves, that Japanese culture is unique. In a way this is true, but not for the reasons often given. Japanese people, Japanese culture, even Japanese religion have not descended in unbroken lines from the actions and ideas of pure Japanese gods, goddesses, and gurus. The rich blend of cultures that comprises the Japan of today is different from that of any other country, but in actuality is the hybrid result of thousands of years of influences, initially from the early civilizations of China, India, and Asia in general, and later from Europe and the United States. Differences from the originals are myriad, as all cultural imports to Japan have faced century upon century of adaptation, refinement, and Japanization.

Even Japan's imperial system, the longest unbroken line of sovereigns anywhere in the world, owes much to ideas borrowed from other Asian courts and countries and then adapted to the needs of Japanese people and society.

Visits to the country's two most ancient extant capitals, Nara and Kyoto, reinforce this sense of Asianness, but also strengthen understanding of the variety and depth of the culture that can be said to be unique to Japan. Animistic Shinto shrines abut Buddhist temples, imperial residences are surrounded by warrens of artisan dwellings, aspects of Japan's violent and militaristic past lie cheek and jowl with memories of great poets and scholars. All of these, however, are not merely museum pieces, but are distinct, almost breathing descendants of the Japan of yesterday. No understanding of modern Japan is possible without at least a cursory knowledge of what Japan was and where its customs and mores come from.

Prior to the founding of Nara (Heijokyo) in 710, Japan did not have a permanent capital city, and it was during the Nara period (646-794) that Japan experienced its first genuine flowering of indigenous culture. Even so, Nara, as was Kyoto later, was chosen because its situation met the requirements of Chinese geomancy, and was laid out according to the precepts of Chinese Tang dynasty town planning. The selection of the site was also probably influenced by the proximity of several important Buddhist temples, such as Horyu-ji, founded in 607.

During the seventy-four years that Nara remained the capital, the strength of Buddhism, not only religiously but politically, grew rapidly and, in fact, it was the overwhelming strength of the monasteries that decided the imperial government to move the capital to Kyoto (Heiankyo) in 794, where it remained until 1868. The Heian period (794-1185) brought centuries of relative peace and prosperity to Japan and can be said to be the true source of Japanese culture as we understand it today.

Both Nara and Kyoto helped define Japan and the Japanese and there is still a great deal to see and experience within both cities that would undoubtedly help today's visitor learn to understand where modern Japan came from and, ultimately, where it is heading.

Ancient stone relics from early civilizations can still be seen in several areas around Nara and Kyoto.

Sakafune Stone at Asuka village in Nara.

The Ishibutai Tomb, thought to be that of Soga no Umako, dates from the seventh century.

Tranquillity is undiluted in and around Nara.

The morning mist shrouds Miwayama before the heat of the day brings a sharpness to the scene.

Lotus leaves spread serenely over the surface of a pond in the recently excavated remains of Nara's Heijo Palace site.

Religion, both native and imported, played an important role in the establishment and growth of both Nara and Kyoto.

The Great Buddha in Todai-ji.

Stone image of Amanojaku, a supernatural creature often described in folk tales, at Takagamo Shrine.

Stone monkey figures at the Kibihime-no-miko burial site inAsuka village.

Pan of the two-and-a-half-mile-long avenue of torii presented over the years by worshippers at Fushimi-Inari Shrine in Kyoto.

A selection of Buddhist statues stands guard at Kamidaigo-ji, Kyoto.

An imperial-style barge traverses Osawano Pond against a striking backdrop of autumn leaves.

The five-story pagoda and the central gate of Horyu-ji are two of the oldest wooden buildings in the world.