Читать книгу The Rasp - Philip MacDonald - Страница 5

INTRODUCTION

ОглавлениеPHILIP MACDONALD was born in London on 5 November 1900. Writing was in his blood. His paternal grandfather was the Scottish novelist and poet George MacDonald and he was a direct descendant of the MacDonalds who were massacred in Glencoe in 1692. MacDonald’s parents were Constance Robertson, an actress, and Ronald MacDonald, a playwright and novelist. The MacDonalds lived in Chelsea before moving to Twickenham, where Philip attended St Paul’s between 1914 and 1915. His publishers later stated that, on leaving school, he ‘enlisted as a trooper in a famous cavalry regiment, and saw service in Mesopotamia’, now Iraq. While full details have not yet been established, his experiences led to the novel Patrol (1927), which was filmed in 1929 and again as The Lost Patrol in 1934 by director John Ford. MacDonald wrote the script for both films, and there are also echoes of Patrol in his script for another film Sahara (1943).

Other than juvenilia, Philip MacDonald’s serious writing career began with a brace of Buchanesque thrillers, which he co-authored with his father. In the first, Ambrotox and Limping Dick (1920), a new drug ‘Ambrotox’ is stolen from a country house and an heiress is kidnapped. The second, The Spandau Quid (1923), is notable for the many small details that prefigure MacDonald’s most famous novel, The List of Adrian Messenger (1959). The Spandau Quid has a frenetic pace and a confusing plot involving smuggled gold, a sunken U-boat and ‘Germans, Sinn Feiners and Bolsheviks’. Both books feature Superintendent Finucane of the Criminal Investigation Department of Scotland Yard, but the policeman is drawn so sketchily that he cannot be considered a series detective.

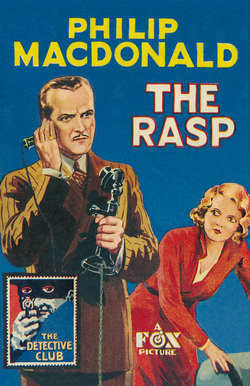

No doubt keen to capitalise on the burgeoning popularity of detective fiction, MacDonald decided to try his hand at what would come to be known as whodunits. His first attempt, The Rasp, was first published ninety years ago (August 1924) and forms the debut of MacDonald’s best-known creation, Colonel Anthony Ruthven Gethryn. The Rasp was widely praised and Gethryn would go on to appear in another eleven detective stories which maintain a generally high standard. They included ingenious murderers (The Choice, 1931), well-realised settings (The Crime Conductor, 1931, set in London’s theatre quarter) and novel concepts (Persons Unknown, also 1931, later published as The Maze, in which the reader and Gethryn are presented with precisely the same information in the form of evidence presented at an inquest).

It is likely that MacDonald saw Gethryn as a romanticised version of himself and, as an amateur sleuth of independent means, MacDonald’s detective has much in common with Dorothy L. Sayers’ rather better-known creation, Lord Peter Wimsey. Born approximately fifteen years earlier than MacDonald, Gethryn—whose unusual middle name is pronounced ‘rivven’—is the son of a Spanish mother and a ‘hunting country gentleman’ as a father. ‘No ordinary child’, Gethryn excelled at school and at Trinity College, Oxford, where he studied History and Classics. After University he travelled extensively before returning home to write poetry and a single, reasonably successful novel before being appointed as private secretary to a Government Minister. On the outbreak of war, Gethryn enlisted as a private in an infantry regiment but a year later he was invalided out and, with the help of his Uncle Charles, became a member of the British Secret Service. By 1919, Gethryn had attained the rank of Colonel and been decorated several times. When Uncle Charles died, he left Gethryn a substantial annual income, equivalent to £400,000 in today’s money. Gethryn promptly settled into a house in Stukeley Gardens, a fictional street in Knightsbridge, London, and resigned himself to a life of leisure from which he quickly tired. In need of distraction, he joined an old University friend to become the co-proprietor of a magazine, and it is in this capacity that the reader discovers him at the outset of The Rasp, ‘tall…with a dark, sardonic sort of face and a very odd pair of eyes”.

MacDonald did not only write about Gethryn. In the 1920s and 30s he penned several other novels and some very good non-series detective stories, including two of the three titles published under the pen name of Martin Porlock: Mystery at Friar’s Pardon (1931) features an outrageously simple solution to a baffling ‘impossible crime’, and X v. Rex (1933) is one of the earliest crime novels to feature a serial killer. Almost all of his books were warmly praised, though some critics noted an increasing tendency to structure his books as if they were a treatment for a film. In fact, MacDonald’s first script was an adaptation of his own novel, Patrol, and the second, Raise the Roof (1930), is generally recognised as the first British film musical.

In 1931, after marrying the writer Florence Ruth Howard, Philip MacDonald moved to Hollywood to focus on writing for the screen rather than the page. His third full script was an adaptation of The Rasp (1932), co-written with another crime writer, J. Jefferson Farjeon. Directed by Michael Powell, The Rasp starred Claude Horton as Gethryn, and was well-received by critics and audiences, but sadly no copies are now known to survive and the film is considered lost. As well as adapting his own work such as Rynox (1932) for films, MacDonald produced many original film scripts throughout the 1930s and 40s, including several for the very popular Charlie Chan series based on the novels by John P. Marquand. Working sometimes with other writers, MacDonald also adapted the work of writers, such as Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca (1930) and Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Body Snatcher (1945); he also wrote the script for two versions of Love from a Stranger (1937 and 1945), adapting Frank Vosper’s stage play, which was itself a heavily reworked version of a play by Agatha Christie, The Stranger, based on her own short story ‘Philomel Cottage’.

Although Philip MacDonald focused on screenplays for the cinema and television during the 1940s, 50s and 60s, he also wrote a small number of novels. These included The Sword and the Net (1941), a well-regarded Second World War thriller published under the by-line ‘Warren Stuart’, and Forbidden Planet (1956), the novelisation of the cult science fiction film of the same title. And after a solitary Gethryn short story, ‘The Wood-for-Trees’ (1947), 1959 saw the publication of the last and—in the opinion of many critics—the best of the Gethryn series, The List of Adrian Messenger. In this thrilling novel, Gethryn identifies the ruthless mind behind a series of seemingly accidental deaths. John Huston’s enjoyable 1963 film of The List of Adrian Messenger starred George C. Scott as MacDonald’s detective, with memorable if somewhat bizarre cameos from Tony Curtis, Burt Lancaster, Robert Mitchum and Frank Sinatra, as well as a brief appearance by Huston himself. The highlight of the film is a fox hunt, a controversial sport in which MacDonald had a lifelong interest. He had been a keen horseman from very young and had an unfulfilled ambition to ride in the Grand National. MacDonald also had a lifelong love of boxing, reflected in Gentleman Bill: A Boxing Story (1922), and he loved dogs—after moving to Woodland Hills in Los Angeles, he and Ruth bred Great Danes.

Philip MacDonald died in California on 10 December 1980. At his best he was among the most innovative of the writers of the so-called Golden Age of detective fiction and, in Anthony Gethryn, he created one of the great gentleman sleuths of the genre.

TONY MEDAWAR

May 2015