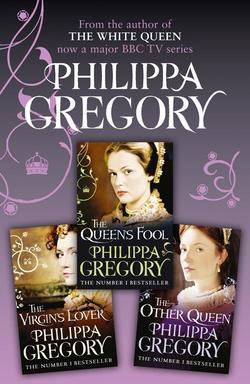

Читать книгу Philippa Gregory 3-Book Tudor Collection 2: The Queen’s Fool, The Virgin’s Lover, The Other Queen - Philippa Gregory - Страница 19

Spring 1555

ОглавлениеTo everyone’s surprise the queen weakened first. As the bitter winter melted into a wet spring, Elizabeth was bidden to court, without having to confess, without even writing a word to her sister, and I was ordered to ride in her train, no explanation offered to me for the change of heart and none expected. For Elizabeth it was not the return she might have wanted; she was brought in almost as a prisoner, we travelled early in the morning and late in the afternoon so that we would not be noticed, there was no smiling and waving at any crowds. We skirted the city, the queen had ordered that Elizabeth should not ride down the great roads of London, but as we went through the little lanes I felt my heart skip a beat in terror and I pulled up my horse in the middle of the lane, and made the princess stop.

‘Go on, fool,’ she said ungraciously. ‘Kick him on.’

‘God help me, God help me,’ I babbled.

‘What is it?’

Sir Henry Bedingfield’s man saw me stock-still, turned his horse and came back. ‘Come on now,’ he said roughly. ‘Orders are to keep moving.’

‘My God,’ I said again, it was all I could say.

‘She’s a holy fool,’ Elizabeth said. ‘Perhaps she is having a vision.’

‘I’ll give her a vision,’ he said, and took the bridle and pulled my horse forward.

Elizabeth came up alongside. ‘Look, she’s white as a sheet and shaking,’ she said. ‘Hannah? What is it?’

I would have fallen from my horse but for her steadying hand on my shoulder. The soldier rode on the other side, dragging my horse onward, his knee pressed against mine, half-holding me in the saddle.

‘Hannah!’ Elizabeth’s voice came again as if from a long way away. ‘Are you ill?’

‘Smoke,’ was all I could say. ‘Fire.’

Elizabeth glanced towards the city, where I pointed. ‘I can’t smell anything,’ she said. ‘Are you giving a warning, Hannah? Is there going to be a fire?’

Dumbly, I shook my head. My sense of horror was so intense that I could say nothing but, as if from somewhere else, I heard a little mewing sound like that of a child crying from a deep unassuageable distress. ‘Fire,’ I said softly. ‘Fire.’

‘Oh, it’s the Smithfield fires,’ the soldier said. ‘That’s upset the lass. It’s that, isn’t it, bairn?’

At Elizabeth’s quick look of inquiry he explained. ‘New laws. Heretics are put to death by burning. They’re burning today in Smithfield. I can’t smell it but your little lass here can. It’s upset her.’ He clapped me on the shoulder with a heavy kindly hand. ‘Not surprising,’ he said. ‘It’s a bad business.’

‘Burning?’ Elizabeth demanded. ‘Burning heretics? You mean Protestants? In London? Today?’ Her eyes were blazing black with anger but she did not impress the soldier. As far as he was concerned we were little more value than each other. One girl dumb with horror, the other enraged.

‘Aye,’ he said briefly. ‘It’s a new world. A new queen on the throne, a new king at her side, and a new law to match. And everyone who was reformed has reformed back again and pretty smartly too. And good thing, I say, and God bless, I say. We’ve had nothing but foul weather and bad luck since King Henry broke with the Pope. But now the Pope’s rule is back and the Holy Father will bless England again and we can have a son and heir and decent weather.’

Elizabeth said not one word. She took her pomander from her belt, put it in my hand and held my hand up to my nose so I could smell the aromatic scent of dried orange and cloves. It did not take away the stink of burning flesh, nothing would ever free me from that memory. I could even hear the cries of those on the stakes, begging their families to fan the flames and to pile on timber so that they might die the quicker and not linger, smelling their own bodies roasting, in a screaming agony of pain.

‘Mother,’ I choked, and then I was silent.

We rode to Hampton Court in an icy silence and we were greeted as prisoners with a guard. They bundled us in the back door as if they were ashamed to greet us. But once the door of her private rooms was locked behind us Elizabeth turned and took my cold hands in hers.

‘I could not smell smoke, nobody could. The soldier only knew that they were burning today, he could not smell it,’ she said.

Still I said nothing.

‘It was your gift, wasn’t it?’ she asked curiously.

I cleared my throat, I remembered that curious thick taste at the back of my tongue, the taste of the smoke of human flesh. I brushed a smut from my face, but my hand came away clean.

‘Yes,’ I admitted.

‘You were sent by God to warn me that this was happening,’ she said. ‘Others might have told me, but you were there; in your face I saw the horror of it.’

I nodded. She could take what she might from it. I knew that it was my own terror she had seen, the horror I had felt as a child when they had dragged my own mother from our house to tie her to a stake and light the fire under her feet on a Sunday afternoon as part of the ritual of every Sunday afternoon, part of the promenade, a pious and pleasurable tradition to everyone else; the death of my mother, the end of my childhood for me.

Princess Elizabeth went to the window, knelt and put her bright head in her hands. ‘Dear God, thank you for sending me this messenger with this vision,’ I heard her say softly. ‘I understand it, I understand my destiny today as I have never done before. Bring me to my throne that I may do my duty for you and for my people. Amen.’

I did not say ‘amen’, though she glanced around to see if I had joined in her prayer; even in moments of the greatest of spirituality, Elizabeth would always be counting her supporters. But I could not pray to a God who could allow my mother to be burned to death. I could not pray to a God who could be invoked by the torchbearers. I wanted neither God nor His religion. I wanted only to get rid of the smell in my hair, in my skin, in my nostrils. I wanted to rub the smuts from my face.

She rose to her feet. ‘I shan’t forget this,’ she said briefly. ‘You have given me a vision today, Hannah. I knew it before, but now I have seen it in your eyes. I have to be queen of this country and put a stop to this horror.’

In the evening, before dinner, I was summoned to the queen’s rooms and found her in conference with the king and with the new arrival and greatest favourite: the archbishop and papal legate, Cardinal Reginald Pole. I was in the presence chamber before I saw him, for if I had known he was there I would never have crossed the threshold. I was immediately, instinctively afraid of him. He had sharp piercing eyes, which would look unflinchingly at sinners and saints alike. He had spent a lifetime in exile for his beliefs and he had no doubt that everyone’s convictions could and should be tested by fire as his had been. I thought that if he saw me, even for one second, he would smell me out and know me for a Marrano – a converted Jew – and that in this new England of Catholic conviction that he and the king and the queen were making, they would exile me back to my death in Spain at the very least, and execute me in England if they could.

He glanced up as I came into the room and his gaze flicked indifferently over me, but the queen rose from the table and held out her hands in greeting. I ran to her and dropped to my knee at her feet.

‘Your Grace!’

‘My little fool,’ she said tenderly.

I looked up at her and saw at once the changes in her appearance made by her pregnancy. Her colour was good, she was rosy-cheeked, her face plumper and rounder, her eyes brighter from good health. Her belly was a proud curve only partly concealed by the loosened panel of her stomacher and the wider cut of her gown and I thought how proudly she must be letting out the lacing every day to accommodate the growing child. Her breasts were fuller too, her whole face and body proclaimed her happiness and her fertility.

With her hand resting on my head in blessing she turned to the two other men. ‘This is my dear little fool Hannah, who has been with me since the death of my brother. She has come a long way with me to share my joy now. She is a faithful loving girl and I use her as my little emissary with Elizabeth, who trusts her too.’ She turned to me. ‘She is here?’

‘Just arrived,’ I said.

She tapped my shoulder to bid me rise and I warily got to my feet and looked at the two men.

The king was not glowing like his wife, he looked drawn and tired as if the days of winding his ways through English politics and the long English winter were a strain on a man who was used to the total power and sunny weather of the Alhambra.

The cardinal had the narrow beautiful face of the true ascetic. His gaze, sharp as a knife, went to my eyes, my mouth, and then my pageboy livery. I thought he saw at once, in that one survey, my apostasy, my desires, and my body, growing into womanhood despite my own denial and my borrowed clothes.

‘A holy fool?’ he asked, his tone neutral.

I bowed my head. ‘So they say, Your Excellency.’ I flushed with embarrassment, I did not know how he should be addressed in English. We had not had a cardinal legate at court before.

‘You see visions?’ he asked. ‘Hear voices?’

It was clear to me that any grand claims would be greeted with utter scepticism. This was not a man to be taken in with mummer’s skills.

‘Very rarely,’ I said shortly, trying to keep my accent as English as possible. ‘And unfortunately, never at times of my choosing.’

‘She saw that I would be queen,’ Mary said. ‘And she foretold my brother’s death. And she came to the attention of her first master because she saw an angel in Fleet Street.’

The cardinal smiled and his dark narrow face lit up at once, and I saw that he was a charming man as well as a handsome one. ‘An angel?’ he queried. ‘How did he look? How did you know him for an angel?’

‘He was with some gentlemen,’ I said uncomfortably. ‘And I could hardly see him at all for he was blazing white. And he disappeared. He was just there for a moment and then he was gone. It was the others who named him for an angel. Not me.’

‘A most modest soothsayer,’ the cardinal smiled. ‘From Spain by your accent?’

‘My father was Spanish but we live in England now,’ I said cautiously. I felt myself take half a step towards the queen and instantly froze. There should be no flinching, these men would detect fear quicker than anything else.

But the cardinal was not much interested in me. He smiled at the king. ‘Can you advise us of nothing, holy fool? We are about God’s business as it has not been done in England for generations. We are bringing the country back to the church. We are making good what has been bad for so long. And even the voices of the people in the Houses of Parliament are guided by God.’

I hesitated. It was clear to me that this was more rhetoric than a question demanding an answer. But the queen looked to me to speak.

‘I would think it should be done gently,’ I said. ‘But that is my opinion, not the voice of my gift. I just wish that it could be done gently.’

‘It should be done quickly and powerfully,’ the queen said. ‘The longer it takes the more doubts will emerge. Better to be done once and well than with a hundred small changes.’

The two men looked unconvinced. ‘One should never offend more men than one can persuade,’ her husband, ruler of half of Europe, told her.

I saw her melt at his voice; but she did not change her opinion. ‘These are a stubborn people,’ she said. ‘Given a choice they can never decide. They forced me to execute poor Jane Grey. She offered them a choice and they cannot choose. They are like children who will go from apple to plum and take a bite out of each, and spoil everything.’

The cardinal nodded at the king. ‘Her Grace is right,’ he said. ‘They have suffered change and change about. Best that we should put the whole country on oath, once, and have it all done. Then we would root out heresy, destroy it, and have the country at peace and in the old ways in one move.’

The king looked thoughtful. ‘We must do it quickly and clearly, but with mercy,’ he said. He turned to the queen. ‘I know your passion for the church and I admire it. But you have to be a gentle mother to your people. They have to be persuaded, not forced.’

Sweetly, she put her hand on her swelling belly. ‘I want to be a gentle mother indeed,’ she said.

He put his hand over her own, as if they would both feel through the hard wall of the stomacher to where their baby stirred and kicked in her womb. ‘I know it,’ he said. ‘Who should know better than I? And together we will make a holy Catholic inheritance for this young man of ours so that when he comes to his throne, here, and in Spain, he will be doubly blessed with the greatest lands in Christendom and the greatest peace the world has ever known.’

Will Somers was clowning at dinner, he gave me a wink as he passed my place. ‘Watch this,’ he said. He took two small balls from the sleeve of his jerkin and threw them in the air, then added another and another, until all four were spinning at the same time.

‘Skilled,’ he remarked.

‘But not funny,’ I said.

In response, he turned his moon face towards me, as if he were completely distracted, ignoring the balls in the air. At once, they clattered down all around us, bouncing off the table, knocking over the pewter goblets, spilling wine everywhere.

The women screamed and leaped up, trying to save their gowns. Will was dumbstruck with amazement at the havoc he had caused: the Spanish grandees shouting with laughter at the sudden consternation released in the English court like a Mayday revel, the queen smiling, her hand on her belly, called out: ‘Oh, Will, take care!’

He bowed to her, his nose to his knees, and then came back up, radiant. ‘You should blame your holy fool,’ he said. ‘She distracted me.’

‘Oh, did she foresee you causing this uproar?’

‘No, Your Grace,’ he said sweetly. ‘She never foresees anything. In all the time I have known her, in all the time she has been your servant, and eaten remarkably well for a spiritual girl, she has never said one thing of any more insight than any slut might remark.’

I was laughing and protesting at the same time, the queen was laughing out loud, and the king was smiling, trying to follow the jest. ‘Oh, Will!’ the queen reproached him. ‘You know that the child has the Sight!’

‘Sight she may have but no speech,’ Will said cheerfully. ‘For she has never said a word I thought worth hearing. Appetite she has, if you are keeping her for the novelty of that. She is an exceptionally good doer.’

‘Why, Will!’ I cried out.

‘Not one word from her,’ he insisted. ‘She is a holy fool like your man is king. In name alone.’

It was too far for the Spanish pride. The English roared at the jest but as soon as the Spanish understood it they scowled, and the queen’s smile abruptly died.

‘Enough,’ she said sharply.

Will bowed. ‘But also like the king himself, the holy fool has greater gifts than a mere comical fool like me could tell,’ he amended quickly.

‘Why, what are they?’ someone called out.

‘The king gives joy to the most gracious lady in the kingdom, as I can only aspire to do,’ Will said carefully. ‘And the holy fool has brought the queen her heart, as the king has most graciously done.’

The queen nodded at the recovery, and waved Will to his dinner place with the officers. He passed me with a wink. ‘Funny,’ he said firmly.

‘You upset the Spanish,’ I said in an undertone. ‘And traduced me.’

‘I made the court laugh,’ he defended himself. ‘I am an English fool in an English court. It is my job to upset the Spanish. And you matter not a jot. You are grist, child, grist to the mill of my wit.’

‘You grind exceeding small, Will,’ I said, still nettled.

‘Like God himself,’ he said with evident satisfaction.

That night I went to bid goodnight to Lady Elizabeth. She was dressed in her nightgown, a shawl around her shoulders, seated by the fireside. The glowing embers put a warmth in her cheeks and her hair, brushed out over her shoulders, almost sparkled in the light from the dying fire.

‘Good night, my lady,’ I said quietly, making my bow.

She looked up. ‘Ah, the little spy,’ she said unpleasantly.

I bowed again, waiting for her permission to leave.

‘The queen summoned me, you know,’ she said. ‘Straight after dinner, for a private chat between loving sisters. It was my last chance to confess. And if I am not mistaken that miserable Spaniard was hidden somewhere in the room, hearing every word. Probably both of them, that turncoat Pole too.’

I waited in case she would say more.

She shrugged her shoulders. ‘Well, no matter,’ she said bluntly. ‘I confessed to nothing, I am innocent of everything. I am the heir and there is nothing they can do about it unless they find some way to murder me. I won’t stand trial, I won’t marry, and I won’t leave the country. I’ll just wait.’

I said nothing. Both of us were thinking of the queen’s approaching confinement. A healthy baby boy would mean that Elizabeth had waited for nothing. She would do better to marry now while she had the prestige of being heir, or she would end up like her sister: an elderly bride, or worse, a spinster aunt.

‘I’d give a lot to know how long I had to wait,’ she said frankly.

I bowed again.

‘Oh, go away,’ she said impatiently. ‘If I had known you were bringing me to court for a bedtime lecture from my sister I wouldn’t ever have come.’

‘I am sorry,’ I said. ‘But there was a moment when we both thought that court would be better for you than that freezing barn at Woodstock.’

‘It wasn’t so bad,’ Elizabeth said sulkily.

‘Princess, it was worse than a pig’s hovel.’

She giggled at that, a true girl’s giggle. ‘Yes,’ she admitted. ‘And being scolded by Mary is not as bad as being overwatched by that drudge Bedingfield. Yes, I suppose it is better here. It is only …’ She broke off, and then rose to her feet and pushed the smouldering log with the toe of her slipper. ‘I would give a lot to know how long I have to wait,’ she repeated.

I visited my father’s shop as he had asked me to do in his Christmas letter, to ensure that all was well there. It was a desolate place now; a tile had come from the roof in the winter storms and there was a damp stain down the lime-washed wall of my old bedroom. The printing press was shrouded in a dust sheet and stood beneath it like a hidden dragon, waiting to come out and roar words. But which ones would be safe in this new England where even the Bible was being taken back from the parish churches so that people could only hear from the priest and not read for themselves? If the very word of God was forbidden, then what books could be allowed? I looked along my father’s long shelves of books and pamphlets; half of them would now be called heresy, and it was a crime to store them, as we were doing here.

I felt a sense of great weariness and fear. For our own safety I should either spend a day here and burn my father’s books, or never come back here again. While they had cords of wood and torches stacked in great stores at Smithfield, a girl with a past like mine should not be in a room of books such as these. But these were our fortune, my father had amassed them over his years in Spain, collected them during his time in England. They were the fruit of hundreds of years of study by learned men and I was not merely their owner, I was their custodian. I would be a poor guardian if I burned them to save my own skin.

There was a tap at the door and I gasped in fright; I was a very timid guardian. I went into the shop, closing the door of the printing room with the incriminating titles behind me, but it was only our neighbour.

‘I thought I saw you come in,’ he said cheerfully. ‘Father not back yet? France too good to him?’

‘Seems so,’ I said, trying to recover my breath.

‘I have a letter for you,’ he said. ‘Is it an order? Should you hand it on to me?’

I glanced at the paper. It bore the Dudley seal of the bear and staff. I kept my face blandly indifferent. ‘I’ll read it, sir,’ I said politely. ‘I’ll bring it to you if it is anything you would have in stock.’

‘Or I can get manuscripts, you know,’ he said eagerly. ‘As long as they are allowed. No theology, of course, no science, no astrology, no studies of the planets and planet rays, or the tides. Nothing of the new sciences, nothing that questions the Bible. But everything else.’

‘I wouldn’t think there was much else, after you have refused to stock all that,’ I said sourly, thinking of John Dee’s long years of inquiry which took in everything.

‘Entertaining books,’ he explained. ‘And the writings of the Holy Fathers as approved by the church. But only in Latin. I could take orders from the ladies and gentlemen of the court if you were to mention my name.’

‘Yes,’ I said. ‘But they don’t ask a fool for the wisdom of books.’

‘No. But if they do …’

‘If they do, I will pass them on to you,’ I said, anxious for him to leave.

He nodded and went to the door. ‘Send my best wishes to your father when you see him,’ he said. ‘The landlord says he can go on storing the press here until he can find another tenant. Business is so poor still …’ He shook his head. ‘No-one has any money, no-one has the confidence to set up business while we wait for an heir and hope for better times. She’s well is she, God bless her? The queen? Looking well and carrying the baby high, is she?’

‘Yes,’ I said. ‘And only a few months to go now.’

‘God preserve him, the little prince,’ our neighbour said and devoutly crossed himself. Immediately I followed suit and then held the door for him as he went out.

As soon as I had the door barred I opened my letter.

Dear Mistress Boy

If you can spare a moment for an old friend he would be very pleased to see you. I need some paper for drawing and some good pens and pencils, having turned to the consolation of poetry as the times are too troubled for anything but beauty. If you have such things in your shop please bring them, at your convenience, Robt. Dudley. (You will find me, at home to visitors, in the Tower, every day, there is no need to make an appointment.)

He was looking out of the window to the green, his desk drawn close to it to catch the light. His back was turned to me and I was across the room and beside him as he turned around. I was in his arms at once, he hugged me as a man would hug a child, a beloved little girl. But when I felt his arms come around me I longed for him as a woman desires a man.

He sensed it at once. He had been a philanderer for too many years not to know when he had a willing woman in his arms. At once he let me go and stepped back, as if he feared his own desire rising up to meet mine.

‘Mistress Boy, I am shocked! You have become a woman grown.’

‘I didn’t know it,’ I said. ‘I have been thinking of other things.’

He nodded, his quick mind chasing after any allusion. ‘World changing very fast,’ he observed.

‘Yes,’ I said. I glanced at the door which was safely closed.

‘New king, new laws, new head of the church. Is Elizabeth well?’

‘She’s been sick,’ I said. ‘But she’s better now. She’s at Hampton Court, with the queen. I just came with her from Woodstock.’

He nodded. ‘Has she seen Dee yet?’

‘No. I don’t think so.’

‘Have you seen him?’

‘I thought he was in Venice.’

‘He was, Mistress Boy. And he has sent a package from Venice to your father in Calais, which your father will send on to the shop in London for you to deliver to him, if you please.’

‘A package?’ I asked anxiously.

‘A book merely.’

I said nothing. We both knew that the wrong sort of book was enough to get me hanged.

‘Is Kat Ashley still with the princess?’

‘Of course.’

‘Tell Kat from me, in secret, that if she is offered some ribbons she should certainly buy them.’

I recoiled at once. ‘My lord …’

Robert Dudley stretched out a peremptory hand to me. ‘Have I ever led you into danger?’

I hesitated, thinking of the Wyatt plot when I had carried treasonous messages that I had not understood. ‘No, my lord.’

‘Then take this message but take no others from anyone else, and carry none for Kat, whatever she asks you. Once you have told her to buy her ribbons and once you have given John Dee his book, it is nothing more to do with you. The book is innocent and ribbons are ribbons.’

‘You are weaving a plot,’ I said unhappily. ‘And weaving me into it.’

‘Mistress Boy, I have to do something, I cannot write poetry all day.’

‘The queen will forgive you in time, and then you can go home …’

‘She will never forgive me,’ he said flatly. ‘I have to wait until there is a change, a deep sea change; and while I wait, I shall protect my interests. Elizabeth knows that she is not to go to Hungary, or anywhere else, does she?’

I nodded. ‘She is quite determined neither to leave nor marry.’

‘King Philip will keep her at court now, and make her his friend, I should think.’

‘Why?’

‘One baby, as yet unborn, is not enough to secure the throne,’ he pointed out. ‘And next in line is Elizabeth. If the queen were to die in childbirth he would be in a most dangerous position: trapped in England and the new queen and all her people his enemies.’

I nodded.

‘And if he were to disinherit Elizabeth then the next heir would be Mary, married to the Prince of France. D’you not think that our Spanish King Philip would rather see the devil incarnate on the English throne than the King of France’s son?’

‘Oh,’ I said.

‘Exactly,’ he said with quiet satisfaction. ‘You can remind Elizabeth that she is in a stronger position now that Philip is on the queen’s council. There’s not many of them that can think straight there; but he certainly can. Is Gardiner still trying to persuade the queen to declare Elizabeth a bastard and disinherit her?’

I shook my head. ‘I don’t know.’

Robert Dudley smiled. ‘I warrant he is. Actually, I know he is.’

‘You’re very well informed for a friendless prisoner without news or visitors,’ I observed tartly.

He smiled his dark seductive smile. ‘No friends as dear to me as you, sweetheart.’

I tried not to smile back but I could feel my face warming at his attention.

‘You have grown into a young woman indeed,’ he said. ‘Time you were out of your pageboy clothes, my bird. Time you were wed.’

I flushed quickly at the thought of Daniel and what he would make of Lord Robert calling me ‘sweetheart’ and ‘my bird’.

‘And how is the swain?’ Lord Robert asked, dropping into the chair at his desk and putting his boots up on the scattered papers. ‘Pressing his suit? Passionate? Urgent?’

‘Busy in Padua,’ I said with quiet pride. ‘Studying medicine at the university.’

‘And when does he come home to claim his virgin bride?’

‘When I am released from Elizabeth’s service,’ I said. ‘Then I will join him in France.’

He nodded, thoughtful. ‘You know that you are a desirable woman now, Mistress Boy? I would not have known you for the little half-lad that you were.’

I could feel my cheeks burning scarlet but I did not drop my eyes like some pretty servant, overwhelmed by the master’s smile. I kept my head up and I felt his look flicker over me like a lick.

‘I would never have taken you while you were a child,’ he said. ‘It’s a sin not to my taste.’

I nodded, waiting for what was coming next.

‘And not while you were scrying for my tutor,’ he said. ‘I would not have robbed either of you of your gift.’

I stayed silent.

‘But when you are a woman grown and another man’s wife you can come to me, if you desire me,’ he said. His voice was low, warm, infinitely tempting. ‘I would like to love you, Hannah. I would like to hold you in my arms and feel your heart beat fast, as I think it is doing now.’ He paused. ‘Am I right? Heart thudding, throat dry, knees weak, desire rising?’

Silently, honestly, I nodded.

He smiled. ‘So I shall stay this side of the table and you shall stay that, and you shall remember when you are a virgin and a girl no longer, that I desire you, and you shall come to me.’

I should have protested my genuine love and respect for Daniel, I should have raged at Lord Robert’s arrogance. Instead I smiled at him as if I agreed, and stepped slowly backwards, one step after another, from the desk until I reached the door.

‘Can I bring you anything when I come again?’ I asked.

He shook his head. ‘Don’t come until I send for you,’ he ordered coolly, very far from my own state of arousal. ‘And stay clear of Kat Ashley and Elizabeth for your own sake, my bird, after you have given your message. Don’t come to me unless I send for you by name.’

I nodded, felt the wood of the door behind me, and tapped on it with fingers which trembled.

‘But you will send for me?’ I persisted in a small voice. ‘You won’t just forget about me?’

He put his fingers to his lips and blew me a kiss. ‘Mistress Boy, look around, do you see a court of men and women who adore me? I have no visitors but my wife and you. Everyone else has slipped away but the two women that love me. I do not send for you often because I do not choose to endanger you. I doubt that you want the attention of the court directed to who you are, and where you come from, and where your loyalties lie, even now. I send for you when I have work for you, or when I cannot go another day without seeing you.’

The soldier swung open the door behind me but I could not move.

‘You like to see me?’ I whispered. ‘Did you say that sometimes you cannot go another day without seeing me?’

His smile was as warm as a caress and as lightly given. ‘The sight of you is one of my greatest pleasures,’ he said sweetly. Then the soldier gently put a hand under my elbow, and I went out.