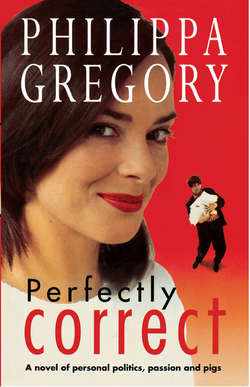

Читать книгу Perfectly Correct - Philippa Gregory - Страница 6

Thursday

ОглавлениеLOUISE, driving back to her cottage after teaching a morning tutorial, had every hope of seeing an empty orchard. Instead, as she rounded the bend that Mr Miles had found so treacherous, she was greeted by the irritating sight of the big blue van and a washing line strung between two of her apple trees. Brightly coloured blouses and shapeless grey underwear were bobbing among the blossom. Louise swore, turned her car down the drive, jerked on the handbrake and marched purposefully towards the orchard.

‘Anyone home?’ she demanded truculently.

The van rocked. First the dog put his head around the door, and when he saw Louise wagged a welcoming tail. Then the old lady herself emerged. She was wearing a man’s smoking jacket in deep plum patterned silk and midnight-blue silk pyjama trousers. ‘You again,’ she said.

‘I think you should move on today,’ Louise said clearly. ‘This is my orchard and you have been here now for more than twenty-four hours. I think it’s time you went. If you want a nearby site I can telephone Mr Miles at Wistley Common Farm for you. He sometimes has a vacant field.’

The woman observed her from under the mop of hair. ‘Out all night,’ she said. ‘Did you go to a party?’

Louise found herself blushing. ‘Of course not. I was at a meeting and then I went on to dinner with friends.’

‘I’ll trouble you for some fresh water,’ the woman said. She reached inside the van and brought out the empty jug again. She jumped lightly down from the steps and strolled towards the gate, the dog at her bare heels. Louise took the jug and marched into the house. A couple of letters were pushed to one side as she opened the door into the porch. She filled the jug and stalked back down the garden path. The old woman was leaning on the gate.

‘Beautiful day,’ she commented. ‘You must enjoy the birds at dawn.’

Louise, who never woke until long after dawn, said nothing.

‘I was born here, you know,’ the old woman said conversationally. ‘In this very cottage.’

Louise could not help but be interested but she remained sulkily silent.

‘The trees were younger then,’ the old woman sighed. ‘The trees were so much younger then.’

She put out an old mottled hand and rested it against a tree trunk as an owner might stroke a favourite dog. There was a strange familiarity between her and the tree, as if the tree were responding to her touch. Louise found herself trying to picture her orchard as a field of saplings, like girls ready to dance. ‘I think you should go today,’ she said, but her voice was no longer angry.

The old woman nodded. ‘As you wish,’ she said. ‘Whatever you wish.’

Louise felt suddenly deflated, as if she had triumphed in some small act of malice.

‘What was your meeting?’ the old woman asked.

Louise shrugged. ‘It’s a committee I belong to. We’re trying to encourage older women to go on university degree courses. Every year we organise an open day and then for those that are interested we run introductory courses. This year we’re focusing on women in science and industry.’ Louise heard her voice sounding flat and indifferent. ‘It’s a very important issue,’ she said.

‘And where did you go for dinner?’

‘To my friends’ house – Toby and Miriam. I used to rent their flat before I came to live here. Miriam and I were at university together. Toby and I…’ Louise abruptly broke off. ‘Toby is her husband,’ she said.

‘Drives a white Ford Escort car, does he?’

‘Why?’

‘I’ve been past a few times. Quite often there was the white Ford Escort parked outside.’

‘Yes,’ Louise said shortly.

The old woman smiled at her benevolently. ‘Quite a friend you are!’ she observed.

Louise could think of no response to make at all.

‘And what d’you teach, at the university?’ the woman inquired pleasantly.

‘I have an experimental post. I’m a specialist in women’s studies seconded to the Literature department on a year’s trial.’

The old woman nodded. ‘Well, I must get on,’ she said as if Louise were delaying her with gossip. She started towards the van.

‘But you are leaving today?’ Louise confirmed.

The old woman turned and waved the gaudy jug. ‘Just as soon as I get packed,’ she said. ‘As you wish.’

Louise nodded and turned and went into the house. She picked up the letters and went to read them in her study. The van, solid and blue, obscured the view of the common which she usually found so soothing. She opened the letters without needing to tear the flaps, glanced at them and put them under a paperweight. She switched on the word processor and picked up the phone to speak to Toby.

‘She says she’s leaving.’

Toby, collecting books for a seminar for which he had failed to prepare, was rather brisk. ‘Good. End of problem.’

‘I feel like a bully.’

‘Napoleon!’

‘Napoleon?’

‘You can’t make an omelette without breaking eggs,’ he said bracingly. ‘Napoleon said it.’

‘She’s so very old. And she was born here. She says she was born here.’

‘She probably says that everywhere she goes. Look, I have to go. I’m supposed to be taking a seminar on industrialisation and I’ve put Das Kapital down somewhere and I can’t find it.’

‘Call me later,’ Louise urged. ‘I feel a bit desolate.’

‘Do some work!’ Toby recommended. ‘Sarah’s waiting for your Lawrence article, she told me this morning. I’ll call you later. I might be able to get out to see you this evening – Men’s Consciousness group is finishing early.’

‘Oh!’ The half-promise was an immediate restorative. Louise often dreaded being alone in the cottage. On cool summer evenings when the swallows swooped and chased against an apricot horizon the cottage seemed too full of ghosts, other people whose lives had been lived more vividly and more passionately than Louise’s. They had left a trace of their desires and needs in every sun-warmed stone, while Louise flitted like a cold shadow leaving no record. Louise felt half-invisible, looking out of the window across the common. She would pour herself a glass of wine and go out into the garden, sit in a deck chair on the front lawn and read a book, consciously trying to enjoy her solitude. Then she would turn around and look at the little cottage which seemed more lively and vital than herself.

It had been built as a gamekeeper’s cottage, part of a grand estate of which Mr Miles’s great-grandfather had bought a small slice. Louise thought of a man like Lawrence’s gamekeeper, Mellors, letting himself quietly out of the gate that led to the common and walking softly on dew-soaked grass to check his rabbit snares. Impossible for Louise to speculate what a man like that would think as he walked down the sandy paths between the ferns, a dark shadow of a dog at his heels. Impossible even to imagine him without the gloss of literature on him. Louise was not even sure what a gamekeeper did for his day-to-day work, she was far better informed about his sexually gymnastic nights. But that was fiction. Everything she knew best was fiction.

The gamekeeper had left when the big estate was sold up. Mr Miles had told her that the cottage was used by his own family and then housed farm labourers. He knew one of his father’s workers who had lived there with his wife and their seven children. Louise had protested that they could not possibly have all fitted into the two little bedrooms.

‘No bathroom,’ Mr Miles had reminded her. ‘So three bedrooms. Girls in one room, boys in another and parents in the third. I used to come down for my tea with them sometimes. It was grand.’ He smiled at Louise, trying to find the words. ‘A lot of play,’ he said. ‘Like foxcubs.’

Louise sometimes thought of that family as she went to sleep alone in her wide white bed. A family where the children played like foxcubs, with four boys in one room and three girls whispering in another and a great marital bed which saw birth and death and lovemaking year after year.

She pulled up her chair and sat down before the word processor.

Nothing came.

Outside in the orchard, the blossom bobbed. The blue van was as still as a rock, planted like a rock, embedded in the earth. The old woman was clearly not packing, she was not moving around at all. She was doing nothing and Louise feared very much that when Toby visited in the evening the van would be there still, and the old woman, who guessed so quickly and knew so much, would see Toby’s white Ford Escort car pull up the drive and watch him get out and let himself in the front door with his own key. Louise thought that with the old woman’s bright eyes scanning the front of the cottage she would not feel at all in the right mood to go upstairs with Toby if he wanted to make love.

She was quite right. The van was still there as the sunset dimmed slowly into a soft lavender twilight. Toby’s tyres sprayed gravel as he pulled up outside the cottage. Louise opened the door at once to draw him in, hoping that the old woman would not see them.

‘Evening!’ the old voice called penetratingly from the bottom of the darkening garden.

Toby turned at once, ignoring Louise’s hand on his sleeve. ‘Good evening,’ he replied.

‘Oh, come in,’ Louise urged. ‘She said she was going, but she’s still here. I’ll talk to her tomorrow and get her moved on. Come inside now, Toby.’

‘I’ll just say hello,’ Toby said. ‘I’m curious.’ He handed Louise the bottle of wine he was carrying and strolled down towards the orchard. The old woman was leaning against the garden gate, her dog sprawled over her bare feet, keeping them warm.

‘Hello.’ Toby smiled his charming smile at her.

The old woman nodded, taking in every inch of him: his silk shirt, sleek trousers, casual shoes, and his jacket slung over his shoulder.

‘And are you at the university too?’ she asked, as if continuing a long conversation.

‘Yes,’ Toby said engagingly. ‘I’m in the Sociology department. Louise teaches feminist studies in the Literature department so we’re colleagues. But tell me, what are you doing here?’

The old woman looked around her as if the briar roses were leaning their pale faces forward to eavesdrop. ‘I’ve come here to write,’ she confided softly. ‘To write my memoirs. I wanted somewhere quiet where I could work.’

‘Really? How very interesting.’ Toby was not interested at all.

She nodded. ‘I was born in 1908. My mother died when I was four. Her health had been broken, you see, by the force-feeding.’

Toby, whose attention had been wandering, suddenly clicked on, like a searchlight. ‘Force-feeding?’

The old woman shook her head. ‘You wouldn’t know. It’s all over and forgotten now. But they were terrible days for the women suffragettes.’

‘I do know,’ Toby said hurriedly and untruthfully. ‘I’ve studied that period. Was your mother a militant suffragette?’

The old woman suddenly gleamed at him. ‘She was! She was! And after her death, they took me in. They called me the youngest recruit of them all! They used to pop me through the scullery windows to check the houses were empty. We cared about pets, you know. If there was a budgie or a canary I’d open the front door and we’d get them out before we fired the building.’

Toby could feel his heart rate speeding. ‘Let me get this straight,’ he said. ‘You were working for the WSPU – the women’s suffrage movement. And they used you, as a little girl, to help them in their attacks on property?’

The old woman nodded. ‘It was like the greatest adventure in the world for me. I used to love going out at night with them, on the raids.’

‘And you can remember it all?’

‘Remember it?’ the old woman laughed. ‘I’ve got a trunk full of photographs and newspaper clippings. I’ve got my diary and my letters. And her diary and her letters too.’

‘Whose diary?’ Toby asked. He had a feeling very like drunkenness. He could feel his head swimming and his breath coming too fast. ‘Whose diary have you got?’

‘Why, the diary of the woman who adopted me,’ the old woman said nonchalantly. ‘Sylvia, Sylvia Pankhurst.’

Toby waded back to the house like a drowning man gasping for the shore. In his fevered imagination he saw the book he would write, the definitive book on the women’s suffrage movement and the inside story of the life of Sylvia Pankhurst. It would be illustrated lavishly with previously unseen photographs. He would quote extensively from her private papers – letters, diaries. He would collate and index them all into chronological order and then deposit them, perhaps at Suffix, perhaps in London. They would be called the Summers collection and he would publish a guide to them. The book would go into many editions. There was a huge and growing interest in anything about the women’s movement, not just in England but worldwide. He would get a teaching post far better paid, far more prestigious than Suffix could ever offer. He could go to Cambridge, or Oxford. He leaned against the front door for a moment, hyperventilating with fantasy.

Oxford, hell! He could go to America! What would the University of California not give for him, and for the Summers collection? He would be able to name his price. The increasingly complex, increasingly competitive world of sociology would be left behind him. He would be into gender studies, he would be an expert on the women’s movement. He was a new man, every inch of him was a new man. He could enter this deliciously easy growth area and leave sociology with its growing emphasis on computers and complicated statistics behind him.

The door opened behind him. ‘Are you ready to come in now?’ Louise asked sulkily. ‘I’ve opened the wine.’

He turned to her, elated, full of his plans. Then some cautious instinct made him hesitate. ‘She’s quite a character,’ he said casually. ‘D’you know why she’s here?’

Louise passed him a glass of red wine. ‘It’s her route, isn’t it? She knew my aunt. She probably comes here every year.’

‘Oh.’ Toby forced the excitement to drain from his face, he controlled his voice so that he sounded nonchalant. ‘Like a gypsy. They always travel the same route, don’t they?’

‘I’ve no idea,’ Louise said. ‘Ask Miriam, it’s more her area than mine.’

As usual, a reference to Miriam signalled Louise’s greatest displeasure. Toby leaned back on the sofa and invitingly patted the cushion beside him. ‘Come and sit here,’ he said. ‘I’ve been thinking about you all day. I couldn’t get you out of my mind.’

Louise could never resist that tone of voice from him. She crossed the room and sat close. Toby slid his arm around her shoulders. His mind was working frantically. He would borrow or buy a tape recorder and persuade the old woman to talk before a microphone. He would make her go through every photograph and every newspaper clipping and identify each one, and all the people in the pictures. He would give each photograph a reference number and cross-refer each one to the tape recording. Then he would lead her through her childhood, from her earliest memories of her mother, through her contact with the Pankhursts and her relationship with them all.

He had lied when he said he had studied the period. He had a nodding acquaintance with the history of the struggle for women’s votes, but no more than any man who has read a couple of history books and lived with a feminist. Both Louise and Miriam would have been better prepared and better suited to interview the old woman. Miriam had taught a women’s history course at evening class, and Louise specialised in women’s studies. Toby did not care. The world was full of better-qualified, better-read, more learned academics and he could not give way to all of them.

There is a point in every academic’s life when he or she realises that a career in a university is as unjust as the upward struggle in any large corporation. Those that survive are those that learn to exploit career opportunities. Those that do well are as unscrupulous and ambitious as any City executive. Toby was not going to hand over the research opportunity of a lifetime simply because he was the wrong gender and had no interest in the topic.

‘So she’s told you nothing of her plans?’ he asked softly. Louise kicked off her shoes and rested her bare feet on the end of the sofa. Toby observed that she had painted her toe-nails a deep sexy red.

‘She’s supposed to be leaving,’ Louise said. ‘She said she’d go today. I’ll make sure she goes tomorrow. I’m at home all day. I’ll pack her up and drive the van myself, if need be.’

Toby smoothed his lips along Louise’s sleek head. When he had first met her and Miriam, Louise had worn her straight hair very short in an unbecoming crop. It had made her face look pointy and sharp. Of the two women, Miriam with her great mop of a shaggy perm and her wide easy smile was undeniably the more attractive. But over the years Louise had grown her hair into a pageboy bob which went well with the increasingly smart clothes she wore. Miriam, who had no time for regular visits to the hairdresser, let the curl drop out of her hair till it was flat and straight . Now she tied it back at the nape of her neck with a leather barrette when she remembered, or an inelegant elastic band; and cut it with the kitchen scissors every month or so.

The faces of the women had changed too. Miriam’s sexy wide-mouthed grin had faded over eight years of arduous and depressing work. When Toby came home late at night and found her dozing in an armchair, a Home Office report open in her lap, he often thought she looked older than her thirty years. Older, and tired and sad. He would wake her and send her up to bed then, full of nostalgic regret for the girl she had been, who used to get drunk on a pint of weak lager and lime at lunchtime, and lie in the sun and refuse to go to her seminars.

Louise’s pointy face had grown rounder and more relaxed. The successful reception of her PhD thesis, the publication of her book, and her particularly lucky slide into her lectureship had put the gloss of a successful woman on her. Her move to the country had given her more time to herself, and Toby was agreeably surprised to find that she seemed to be spending this time on personal grooming, of which the claret toes were the latest example. Louise contributed to a quarterly paper of feminist theory. Toby had just read her essay which explained that feminists now could legitimately wear any kind of garment, adopt any sort of adornment. The old dreary dress codes of puritan drabness could be rejected. Apparently feminists could now enjoy their femininity. Indeed, any kind of aping of male dress style – whether boiler suit or power dressing in a tailored jacket – was a betrayal of their true sexuality. Lace underwear, even stockings and suspenders, was part of a woman’s personal choice and a legitimate statement of her individual power.

Toby found this development of feminism intensely enjoyable. No enthusiast had greeted the Second Wave more ardently. He slid an exploratory hand under the collar of Louise’s shirt and felt the thin strap of something which might be a bra, or might be some kind of teddy or body stocking. He knew himself to be a remarkably lucky man. His youth had coincided with the period of time where women demonstrated their emancipation by leaving off their underwear, refusing to shave their body hair, and participating in promiscuous sex. A state as near to Paradise as the mid-twenty-year-old Toby could imagine. Now he was older and his tastes were more refined he had the remarkable good fortune to discover that feminism had taken a developmental turn. Body hair was now removed, personal adornment was a sign of confidence and pride, and although promiscuity was out of fashion, celibacy – that spectre of the late ‘80s – had never caught on. Provided a man was prepared to wear a condom (and Toby was always thoroughly prepared), he could expect to find most serious intelligent women dressed in underwear appropriate to a fin-de-siècle Parisian brothel, and open to invitations of the most imaginative nature. Toby let his hand stray downwards to Louise’s right breast. She seemed to be encased in a kind of silky lace. ‘Shall we go upstairs?’ he asked politely.

Louise smiled in assent and led the way. She glanced over her shoulder to the blue van in the orchard. It was still and quiet. No lights were showing. Perhaps the old woman was having an early night prior to a long journey at dawn tomorrow. Louise resolutely put her from her mind and opened the bedroom door.

Miriam and Toby’s bedroom at home was functional – part library, part sleeping area. Toby often worked in bed and the floor and table on his side were often littered with papers and books. The telephone was Miriam’s side with a notepad and pencil for late-night emergency calls. Toby loved the contrast of Louise’s orderly female room. There were no frills or lace, nothing fussy, but the room had a groomed elegance – like Louise herself. There was a pure white quilt on the modern brass bed. There were complicated and faintly erotic prints on the freshly painted walls. On Louise’s uncluttered dressing-table were a few small bottles of perfume. On her bedside table was a promising bottle of aromatherapy massage oil. The electric blanket had been switched on since the late afternoon; Louise disliked cold sheets. Toby undressed without haste and laid his clothes carefully on a chair. Louise stripped down to her lacy teddy, threw back the covers of the bed and spread herself out for his view.

‘Gorgeous,’ Toby said appreciatively, and slid on top of her.

He did not stay there for more than a moment. Toby’s lovemaking followed a certain pattern which both Miriam and Louise had learned. He moved easily from one position to another with the woman on top, or at his side, but rarely beneath him, a position which had been unpopular with feminists in the old days, when Toby learned his erotic skills. He varied the rhythm of his movements from very fast to languidly slow. He neglected no erogenous zone with his fingers or his tongue with the meticulous thoroughness of a man checking off a mental list. He talked to Louise (or Miriam) not only about his feelings and desires, but he also inquired courteously as to their progress. ‘Is this good? And this? Do you like it when I do this? And this?’ Whether he was trying to please or inviting congratulations, it was impossible to say.

When he was ready to come to orgasm which, with Louise (and Miriam), was these days rather soon, he would smile a peculiarly attractive smile and take Louise’s (or Miriam’s) hand, lick the middle finger and place it lovingly but firmly on her clitoris. Thus prompted, Louise (or Miriam) would caress herself to a climax while Toby gave himself up to the bliss of his ejaculation with a clear conscience.

Today, as other days since Louise’s move to the cottage, their lovemaking was pleasant rather than overwhelming. The night before, in the car, they had been desperate for each other’s touch. The fact that the half-hour was stolen from Miriam’s meeting spiced the taste of each other’s mouths. In the morning, in Toby’s spare bedroom, Toby had chosen a little light sensual teasing, but had refused to make love. He often chose to withhold himself from either his wife or his mistress for Toby was a true gourmet, he liked the taste of desire, he did not have to consume the whole banquet. Also, as his relationship with Louise and Miriam had become part of his domestic routine, he found he enjoyed the knowledge of their desire for him even more than consummation. He liked leaving them aroused, he preferred them dark-eyed and slightly breathless to slack and satisfied. He enjoyed playing with Louise in the morning and then catching sight of her at work, knowing that she was still turned on. Both women serviced his ego as much as his libido.

Toby and Louise on her big bed made love with a sense of familiar enjoyment rather than excitement. Perhaps they were sated, perhaps their minds were distracted by the old lady at the bottom of the garden. But Toby knew that the problem went deeper than that. By some unfortunate trick of fate he now only became deeply excited if there was a possibility of discovery. The car in the lane on the South Downs in the evening light was as dizzy an encounter as any of their earlier moments. Louise in Miriam’s house – when Miriam might return at any moment – was Louise at the very pinnacle of her desirability. Louise in her own house, with the front and the back door safely locked, was too secure to give him that swift, sweet illicit thrill. It was an encounter as safe as those of his marital bed. He went through the erotic motions, and he reached a climax. But it was nothing like the pleasure of having Louise under Miriam’s very nose.

Toby did not know it, and Louise would never have admitted it – not even to herself – but it was exactly the same for her too. They had, both of them, become addicted to guilt and mistaken it for love.

Toby and Louise ate cheese, biscuits and soup sitting either side of the kitchen table. Toby glanced at the clock.

‘I have to go,’ he said. ‘I said I’d be home at ten.’

‘Have you been here?’ Louise asked. She always practised the permanent mistress’s courtesy of priming herself on his deceptions.

‘No. With a graduate student,’ Toby said. ‘James Sutherland, playing pool.’

‘You smell wrong,’ Louise cautioned. ‘Not smoky enough.’

‘He has a pool table at his house.’

Louise raised her eyebrows. ‘Our students are going up in the world,’ she observed. ‘Which one is he?’

‘The one who drives the white Porsche,’ Toby said grimly. ‘God knows where they all get their money. D’you know, I teach a group of undergraduates who are sharing a house – but they’re not squatting, they’re not even renting it, they’re buying.’

Louise nodded. ‘The student bar has started stocking Lanson champagne. God! When we were undergraduates we used to save up for Friday nights and then get drunk on cider and gin.’

Toby chuckled. ‘Did you really?’

‘We called them “Happies”.’

Louise remembered wrongly. She had mostly stayed sober to study. It was Miriam who was the sybarite in those days. ‘Miriam and I used to drink three each and then fall off our bar stools.’

‘I never saw you fall off your bar stools,’ Toby said with regret.

‘You met us in our finals year,’ Louise reminded him. ‘Our salad days were over then. It was all continuous assessment when we were students. We were on the rack from September to June.’

‘But more thoroughly assessed,’ Toby prompted.

He and Louise had fought an easily defeated campaign to preserve the university’s practice of continuous assessment, in which students demonstrate their learning and research skills with work written over weeks of preparation. In practice, the conscientious ones worked themselves into a stupor of fatigue with week after week of late nights and early mornings, while the lazy ones drank to excess and fooled around until two days before the deadline when they went into a frenzy of last-minute labour. The results were broadly comparable.

The university, weary of supervising students rushing to extremes, had instituted the convention of a finals exam fortnight so that all the breakdowns and alcoholism and suicides were concentrated into one short, manageable period.

Louise and Toby had fought this change on the grounds that it was a deviation from the radical nature of the university. Of course, no-one had ever proved that continuous assessment was more or less radical than examinations, and once continuous assessment was adopted as the Conservative government’s policy for GCSEs it had rather gone out of fashion as a Cause. Nonetheless Toby and Louise still loyally paid lip service.

‘I learned more in my final year than I did in the other two put together,’ Louise said.

‘I wish I’d had that opportunity,’ Toby sighed, hypocritically hiding his pride in his own degree. ‘Finals fortnight at Oxford was madness.’

He glanced at the kitchen clock, drained his glass of wine and stood up. ‘See you tomorrow.’

Louise followed him from the kitchen to the sitting room and passed him his jacket. She was attractively dressed in a silky dressing gown. Toby had a moment’s regret that he was leaving her to go into the cool summer night and drive home to Miriam who would be irritable and worried from her meeting at the Alcoholic Women’s Unit.

‘I’m not coming in to university tomorrow,’ Louise reminded him. ‘I shall make sure the old woman moves on and then I’ll work here all day. I’m overdue on that Lawrence essay.’

Toby hesitated. It would be fatal to his plans if the old woman disappeared again into the lanes of Sussex with her precious bundle of primary sources and her irreplaceable oral history. But he could not think of any reason to stop Louise from moving the trespasser on her way. All he could do was delay her. ‘I’m free in the morning,’ he said. ‘I’ll come out and have breakfast with you. I’ll bring fresh croissants and the newspapers.’

Louise lived far beyond the restricted village paper round which was organised by Mrs Ford from the village shop and delivered only to her particular favourites. Louise adored reading the Guardian over breakfast. Toby had played one of his strongest cards.

‘Oh, how lovely!’ she exclaimed. ‘To what do I owe the honour?’

Toby smiled his engaging smile. ‘Oh, I don’t know. I just thought we could spend the morning together. Don’t get up before I arrive and I’ll bring it up to you in bed. I’ll be here by nine.’

Louise wound her arms around his neck and kissed his cheek and his ear. ‘Lovely lovely man,’ she said softly.

‘Promise you won’t get up?’ Toby demanded cunningly. ‘I don’t want you to spoil the mood by worrying about the old lady. You stay in bed until I come.’

‘Promise.’

He released her and she watched him walk from her front door to his car. Then she shut the front door and went to the kitchen to clear the plates from supper. She was thoughtful. This was the first time Toby had offered to bring her breakfast since the move to the cottage. In the old days, in her little studio flat, he had often climbed the stairs with his copy of the Guardian and croissants hot from the bakery in a greasy paper bag, after Miriam had left for work. The transition of this tradition to the cottage could only indicate his increasing commitment.

She wiped down the pine table with a sense of fluttery excitement. Toby had been with her this morning, teasing, withholding, but playing with her and not his wife. He had been with her all evening, and now he was coming to breakfast. His movement towards her was evident. Since the start of their affair Louise had wanted him to choose her. The underground half-conscious competition between close women friends meant that Louise and Miriam were always rivals. The women’s movement’s insistence on loving sisterhood had meant that both women totally ignored this. If challenged they would have denied any feeling of rivalry; but in fact Miriam was always worried that she had made the wrong career choice when she decided to work for the refuge and leave the academic life which had been so good for Louise; while Louise’s sexual confidence would always be undermined by her memory of the three long summers when Miriam attracted scores of young men by doing nothing more seductive than lying on the grass and picking daisies. Only one thing could restore Louise to a proper sense of her own worth – Toby.

Louise went through to her study to collect the vexing copy of The Virgin and the Gypsy to re-read once more in bed. A glimmer of golden light from the bottom of the orchard caught her eye. Now there was a woman who seemed to need no man at all. No friend, no husband, no lover, certainly not the husband of her best friend. Louise stood for a little while in the darkness of her study looking out at the friendly little light, considering the old lady. There was a woman who seemed powerfully self-contained. Not a property-owner like Louise, not a career woman like Louise. Not a sexual object like Louise – left alone again, despite her silky sexy dressing gown. A woman who had avoided all the opportunities and all the traps open to the modern woman. A woman who had been born into a society markedly less free, a woman who enjoyed none of Louise’s opportunities and enhanced consciousness but who was, nonetheless, an independent woman in a way that Louise was not.

Louise speed-read the whole of The Virgin and the Gypsy before she went to sleep. Although she had taken English Literature as her BA and was now a women’s specialist in the Literature department, Louise was quite incapable of understanding either fiction or poetry. All of it was judged purely on its attitude to women. She had learned the jargon and skills of literary criticism. She could point to an adjective and detect imagery. But the heart of her interest in writing was neither the story nor the telling of it, but its attitude to the heroines.

Any work of fiction could thus be simply de-constructed and simply scored on a grade of say one to ten, entirely on the basis of its position on women. The language might be living vibrant poetry, the story might bypass Louise’s critical pencil and plunge straight into her imagination, but still she would work through the pages going tick, tick, tick in the margin for positive references to women, and cross, cross, cross for negative imagery. A piece of blatant sexism would be flagged with a shocked exclamation mark. The Virgin and the Gypsy was spotted with outraged exclamation marks by the time that Louise’s bedside clock showed midnight and she had finished re-reading it.

She closed the book carefully and put it on her bedside table. She set her alarm clock for quarter to eight. She had promised Toby that she would not get up before he arrived with her breakfast but she was not going to be found in bed in her brushed cotton pyjamas, her hair tangled, and her mouth tasting stale. When Toby arrived, thinking he was waking her, she would have already showered with perfumed shower gel, cleaned her teeth, brushed her hair, and changed into silk pyjamas which matched the dressing gown she only wore for Toby’s visits.

She glanced towards the darkened window. There was a pale wide moon riding in the skies over the darkened common. An owl hooted longingly. Up the little lane came the strangled roar of a Land-Rover in the wrong gear: Mr Miles driving home after a late night at the Holly Bush. The sound of the engine faded as he turned the corner towards his solitary darkened farm and then everything was quiet again. Louise turned on her side and gathered her pillow into her arms for the illusion of company, and slept.

She dreamed almost at once. She was in Toby and Miriam’s house but the road before their front gate was a deep brown flood of a river. At the edge of the churning waters, where the waves splashed and broke against the front doorsteps, was a tossing flotsam of paperbacks, their pages soggy and sinking in the dark waters, their covers ripped helplessly from the spines and rolling over and over in the turbulence of the flood.

Louise began to be afraid but then realised, with the easy logic of dreams, that she could go out of the back door, into the little yard and through the backyard gate, where she put out the dustbins on Thursdays. From the backstreet she could go to the university, to her office, where there were plenty of books to replace those that were rushing in the flood past the house, torn and soggy. She went quickly through the kitchen and flung open the back door.

It was the very worst thing she could have done. With an almighty roar, like that of some wild and uncontrollable animal, the flood water rushed towards her, far higher and more violent than it had been at the front. Louise fled before it as it tore the notes from the cork pin-board and clashed saucepans in their cupboards. The larder door burst open and packets of cereals and rice tumbled out into the boiling waters. Toby’s wine rack crashed down and the bottles broke, turning the water as red as blood and terrifyingly sweet. Louise ran for the stairs, the red waves lapping and sucking at her feet as the current eddied and flowed through the ground floor of the house. She screamed as she grabbed the newel post at the bottom of the stairs but there was no answering call from above. She was alone in the whole world with the hungry waters after her.

She staggered up the stairs as a fresh high wave billowed in through the kitchen door. With a crash the front door fell in and the two rivers merged, swirling, in the hall. The scarlet waters’ terrible load of tumbling books chased Louise up the stairs, past Toby and Miriam’s bathroom and bedroom, up the little stairs to her own flat.

There was someone in her bed. A man. For a moment Louise recoiled in fear, and then the crash behind her, as the stairs gave way, made her run into the room and fling herself on him, terrified at last into desire. She was screaming, but not for help. She was screaming: ‘I’m sorry! I’m sorry! I’m sorry!’

Louise wrenched herself from sleep with a gasp of terror. Her pillow, gripped in her arms, was damp with warm sweat. Her hair was plastered to her neck as if she had indeed been washed by the waters of that strange dream flood. She swallowed painfully, her throat was sore. She unclenched her fists, she released the pillow.

Her bedroom was very quiet. The clock ticked very softly. She looked towards the window. Dawn was coming, the first she had ever seen in the country. In the soft pearly light of the early morning a few solitary birds were starting to sing. Louise raised herself up in her bed and looked down towards the orchard. The blue van was there, with a tiny wisp of smoke coming from the skewed chimney. The van was rocking slightly as the old woman inside moved about, making breakfast for herself and the dog. Louise sniffed. She could smell a safe warm smell of woodsmoke. She felt enormously comforted at the sight of that battered blue roof and the presence of another person nearby. She dropped back to the pillows again and fell asleep like a child that is reassured by the sound of her mother in the next room. There was, after all, nothing to fear.