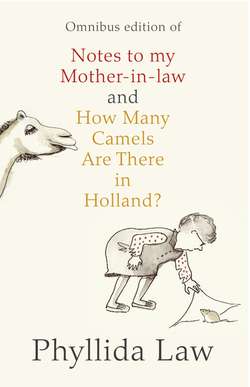

Читать книгу Notes to my Mother-in-Law and How Many Camels Are There in Holland?: Two-book Bundle - Phyllida Law, Phyllida Law - Страница 7

Emma

ОглавлениеIt’s rather difficult to write about one’s mother while she’s still alive. There could be consequences. But the first thing that pops into my head is that she’s a tough act to follow. Long ago I remember deciding that I could never be as good, kind, wise, loving and generally brilliant and gorgeous as her. It’s taken me over half a century to stop trying.

Stepping back, I see her more clearly. I remember her giving me a birthday tea when I was about five or six – she baked scones and fairy cakes, dressed up as a waitress and served us as if we were in a Lyon’s Corner House. I think her hat was made from a doily.

When we were ill or hurt she always soothed us in Gaelic. She sang us lullabies and rubbed hot oil on our chests in winter.

The only time she has ever evinced pride in something I’ve done was when I told her, backstage at a Footlights gig, that I had received a good result in my degree. She screeched for joy and I felt ten miles high. She expresses pride in her grandchildren, though, which prompted my sister to suggest, with benevolent tartness, that perhaps it (pride) skipped a generation.

We’ve worked together many times, and I once wrote a very long monologue for a TV programme back in the day when autocue didn’t exist. I’d learnt it but it was full of repetition and proved rather difficult. Mum, who was in the show as well, watched every take and when I got it wrong for the umpteenth time, she marched over the stage with her skirts pulled up over her bum to cheer me up. She’d forgotten that she wasn’t wearing knickers under her tights though. It got me through, I can tell you. And the crew.

She’s a stoic but her stoicism is rooted in humour. I have never witnessed her grieving in a life dotted with rich opportunities for grief. But I have seen her laughing a lot.

I have profound respect for her brain and as we have, one way or the other, been very much together since my father died, I credit her with the development of my own writing. I used to do a bit of stand-up and I would rehearse every set in front of her, cold, in the kitchen, and she was startlingly accurate about what worked and what didn’t.

It’s difficult for people who know her now to imagine but, like her mother before her, she could be fierce. Once, when I was seven or so, I picked a bluebell from a garden as we were walking down the road. Mum marched me, sobbing with fear (me, not her), to the door of the house and made me confess and give it back. Guilt’s big in our family.

Dad once said to me, ‘You’re a taker, Em, and I’m a taker, but your mother is a giver.’ That wasn’t much of a help, I have to tell you. When we moved from our flat into a house which was only round the corner she did a lot of the removals herself. I can see her walking up the hill wearing a lot of khaki and a saucepan on her head. When we were little she was always stripping something made of old pine.

I did witness her, on occasion, sacrificing her own pleasure for the sake of my grandmothers or her ailing brother or her sick husband or her two demanding daughters and, as she says, it could be construed as a fine way to avoid living your own life. But it doesn’t quite wash. She has always worked, with hiatuses of course, but she has always gone back to work – as an actor and now as an author. I do concede, however, that it may have helped her to avoid another relationship. Some years ago she went on a date with a friend’s father. I think he tried to kiss her in the cab. She’s never recovered.

Maybe the qualities in her writing describe her better than I can: it’s spare, full of curious and telling detail and mysterious ellipses, very funny, touching without trying to be, connected to every little action of every little day, and in character quite unlike anything else I have ever read. Except perhaps Montaigne, who was equally intrigued by the quotidian business of being human.

The best bit of the day is around about 6pm when one of us rings her, says, ‘The bar’s open,’ and hangs up. By the time I’ve poured a slug of decent red wine, she’s putting her key in the door. I’ll hand over the glass and she will invariably say, ‘Ooh. I’ve been looking forward to that all day.’ Then we share the news.