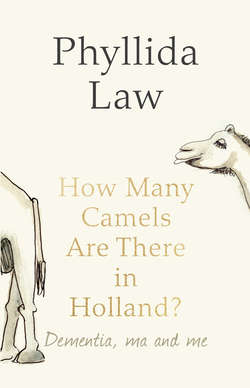

Читать книгу How Many Camels Are There in Holland?: Dementia, Ma and Me - Phyllida Law, Phyllida Law - Страница 6

IN THE BEGINNING

ОглавлениеMy mother, Meg, was the seventh of eight children and the youngest of five sisters born to a Presbyterian minister and his tiny indomitable wife, who lived to terrorise us all.

Mother remembered very little about her papa, except that he wore a velvet smoking jacket of an evening and kept a bar of nougat in his breast pocket for little fingers to find. They had sweets only on Sunday when they spent the day in church, eating lunch and tea in the vestry, after which sweets would be found on the church floor, dropped accidentally-on-purpose from velvet reticules by little old ladies.

Papa died young. Grannie went into mourning and took her eight children to Australia, where her brother was a professor at the University in Sydney. Mother was still wearing woollen hand-me-downs. When Grannie became ill the doctor advised a return to a cooler climate. The children were perfectly willing. Ripe mangoes were nice, but locusts were nasty. They took the boat home in 1913. Grannie said there were spies on board, and her beautiful Titian-haired daughters caused havoc among the crew. Aunt Mary got engaged to a sailor, who went down with Kitchener in 1916.

Back in Glasgow, in reduced circumstances, they squashed into a small ground-floor flat near the university and Aunt Lena (who married a millionaire and died on a luggage trolley in Glasgow Central Station) looked after them all. Mother told stories of beds in cupboards and wild nights by the kitchen fire, drinking hot water seasoned with pepper and salt.

The boys went to war and the girls became secretaries. Ma, the youngest, went to a cookery college affectionately known in Glasgow as the Dough School, where she started her career as an inspired cook and learnt to wash walls down before New Year with vinegar in the rinsing water. Then she joined her sisters at the Glasgow Herald offices where she met my father.

He must have been a stumbler for a girl. Handsome, gifted and wounded in the First World War, I think he had what we now call post-traumatic stress disorder. I don’t know when Ma ripped her mournful wedding pictures out of the family album, but seven-year-olds are perfectly able to recognise unhappiness.

I only met Father properly years later, after he had eloped with his landlady’s daughter, but I was eighteen by then and it was too late for love.

I remember 3 September 1939 and the outbreak of war. We were to be evacuated. It sounded painful and some of it was. At school we were just ‘the evacuees’, ‘wee Glasgow keelies’, and they snapped the elastic on my hat till my eyes watered. I caught fleas and lost my gas-mask. James, my brother who was twelve, wet the bed, got whacked with a slipper and ran away back to the bombs. I was left behind. My mother and my brother were now half-term and holiday treats. Thinking about it now, I feel bereft. I missed such a lot of warmth. Mother was good at warmth. She always had a gift for dispelling gloom, a useful talent in 1940s Glasgow, which must have attracted Uncle Arthur who, though witty, had a dark side. He used to cheer himself up with the aunts – their brother John was his best friend – but they were all spoken for, so when Mother was divorced he came courting.

She had taken a job in a ladies’ boutique called Penelope’s, opposite Craig’s tea-rooms and next to the Beresford Hotel on Sauchiehall Street. Here she kept the accounts in a huge ledger in a very neat hand, wearing a very neat suit.

On Saturday, she served everybody in the back shop delicious savoury baps before she locked up. I loved the back shop, where Mother removed Utility labels from clothes and replaced them with others she had acquired. Now and again, if she came by a good piece of meat, she would sear it on a high flame on the single gas ring, wrap it in layers of greaseproof paper, a napkin and brown paper and send it by post to anyone she thought deserving at the time.

Arthur and Ma married when I was thirteen and away at boarding school in Bristol. They were very happy. Mother had discovered that men can be funny. If ever I was in a position to phone home, they were never being bombed. Instead they were playing riotous games of ‘Russian’ ping-pong.

One bomb did bring down all the ceilings in the close stairwell with such a rumbling crash that Joey the budgerigar flew up the chimney and never came down again.

Whatever was happening, Ma always travelled down to Bristol at half term wearing an embarrassing hat on loan from Penelope’s. If there was a patch of blue in the sky large enough to make a cat’s pyjamas, she would let out piercing yelps, ‘Pip-pip’, and sing in the street. She also got me seriously tipsy on scrumpy, which she thought sounded harmless.

She and Uncle Arthur moved from their flat to look after Grannie in Aunt Lena’s enormous house, where they grew vegetables and longed for their own plot. Every holiday we went for long drives into the country to find the cottage of their dreams. We never found it. Not till I’d married and had a baby.

My husband and I met at the London Old Vic when we ‘walked on’ in Romeo and Juliet. I was a Montague. He was a Capulet. We didn’t speak much. But later we all had a very good time at one of the early Edinburgh Festivals, and joined a company that toured the West Country in a bus that held our sets and costumes; we ended up at the Bristol Old Vic in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, when we proposed to each other. I was Titania. He was Puck.

We got married on a matinée day. Mother bounced into my bedroom that morning, wearing a hat that looked like a chrysanthemum. ‘If you don’t want to do this, darling,’ she said, ‘we’ll just have a lovely party. It’ll be fine.’ I felt that explained her mournful wedding photos. No one had offered her an escape route.

It was May. The sun shone. Uncle Arthur gave me away and Mother blew kisses at the vicar. Then the family party, with assorted aunts, drove to France and we went to give a performance.

I wonder what it was like.

We found a flat in London where you filled the bath with a hosepipe from the kitchen tap. We were happy and in modest employment. My new husband took a job as a ‘day man’ backstage at Sadler’s Wells.

Two years later, we had our daughter Emma. It was April. Just in time for the holidays. We had a phone call from Ma. ‘I’ve taken a house on the Clyde,’ she announced, like an Edwardian matron. ‘I want the baby to start life in good fresh air.’

The weather was appalling. The sea and the sky merged in battleship grey, chucking water at the windows, and our landlady was an alcoholic, who hid our cheques and had regular visits from the police. We took our tin-can car along the purple ribbon of a road that led to the village of Arden-tinny, asking at every BandB if they had room for us. They did, but they were too expensive. Then the wind changed and the weather was sublime. We stopped at the Primrose tea-rooms in the village for an ice-cream, and I sat on the jetty with the baby, dangling my feet in the loch and nibbling a choc ice.

My husband wandered away down the village street to find the phone box, saying that Mrs Moffat in the tea-rooms had told him there were rooms to let in a cottage close by. I had barely finished my ice when he came thundering back down the road at uncharacteristic speed. ‘We’ve got it,’ he said. ‘It’s five pounds for a fortnight. Go and look. Give me Em.’ As I left he called, ‘It’s not the prettiest cottage. It’s the one next door.’

Well – The prettiest cottage was empty.

The prettiest cottage was for sale.

The prettiest cottage was exactly what Uncle Arthur and Ma had been searching for for more than a decade.

We pooled our resources and bought it.

The cottage has had nine lives already. Mother and Uncle Arthur outgrew it and moved to an old manse a short trot along the shore road, where they cultivated their vegetable patch and their soft-fruit cage.

In their eighties it became too much for them. Should they move back to the cottage?

Mother was excited.

Uncle Arthur was depressed.

Moving house didn’t help, I suppose. The idea to scale down and live in the cottage had been mooted, applauded and discarded at my every visit, year after year. The morning room became a dump for ‘stuff’. Old mattresses, an ancient TV, worn-out bedding and pillows, old saucepans and a toaster, a gramophone, gardening tools, two fishing rods and one galosh.

Mother’s confidence was gradually dented by falls on the stairs, with coffee in one hand and a portable wireless in the other. Uncle Arthur just fell down backwards. Then there was the discovery we made, while investigating a damp patch in Ma’s bedroom, that the roof void was full of bats. They would squeeze through a chink in the plaster round one kitchen pipe and very slowly move down, paw over paw, till Uncle Arthur caught them in a dishcloth and threw them out. Any remarks about protected species did not go down well.

He was ruthless with mice. He put stuff under the sink that looked like black treacle and the mice got stuck in it, like flies on fly-paper, whereupon he lifted them by the tail and flushed them down the outside loo. And that was another thing: no downstairs loo, except the one outside. Tricky.

Then there was the car and the undoubted skill needed to park it off the road and up the steep drive, then some very dodgy manoeuvres to get down again. And there was the time they were struck by lightning. Both phones blew off the wall, filling the house with acrid smoke, and four neat triangular flaps appeared on the lawn, as if someone had lifted the turf with a sharp blade. Spooky.

That New Year the Rayburn exploded. The kitchen walls and every surface were coated with black oil that took three days to lift, and Uncle Arthur, trying to be helpful, threw himself on to the fire in the sitting room along with a log. Sage discussions took place over arnica and quite a lot of whisky. They would move to the cottage in the spring, they agreed, but by the time I left for London, the kitchen was as good as new and they had changed their minds. There was no question of their ever leaving the old place.

That very week I signed a contract to appear in La Cage aux Folles at the London Palladium.

Exciting!

Mother rang that evening.

They had sold the house. It was a bad moment. I don’t sob a lot – well, I do now, perhaps, but I didn’t then. Too vain. My nose would swell to the size of a light bulb. It still does, but now I don’t care.

My agent must have been surprised to hear me on the phone after hours and inarticulate, hiccuping with shock.

‘This is not some flibbertigibbet actressy thing,’ I managed to yelp. ‘This is serious.’ She took it as such, tried to get me released and failed. The American producers said I would have to pay for all the printed publicity if I left, but I would be allowed to negotiate a week’s holiday to include Easter weekend, which extended it a little. My stand-in was alerted and I bet she was good. No one complained. They didn’t miss me at all. That’s always a worry.

Mother greeted the news of my foray into musical theatre with real delight. Also, she and Uncle Arthur actually seemed excited about their early move. I hadn’t bargained for this burst of energy. They were like teenagers, walloping into the Bulgarian plonk and spending happy hours throwing unwanted belongings into the morning room, then taking them back.

Their lovely garden was now less of a burden and seemed, perversely, to flourish on neglect. The vegetable patch was declared redundant and the soft-fruit cage dismantled. Any leaks in the roof were belittled. It only leaks when it rains and the wind is in the wrong direction, they said. Well, Uncle Arthur said. He didn’t want to worry the new owners.

I learnt a great lesson from all this. When you’re old, as I am now, you must have a ‘project’. It can be quite modest, but you must have one. It creates a future for you. It lifts the spirits.

Mine were lifted, too, by riotous rehearsals. I love dancers. I love their energy, their discipline and their courage. And besides all of that, the chorus in Cage were funny.

I had a small part and a huge dressing room, which was, apparently, half of Anna Neagle’s when she’d played the Palladium. Just along the corridor there was an even larger dressing room filled with male dancers dressed appealingly in cami-knickers, bras, high heels and a large amount of make-up.

Between shows on Wednesday, they organised competitions for, let’s say, the most original contents of a handbag. The Best Hat Award was won, I remember, by a dancer wearing a wide-brimmed bush hat decorated with tampons.

I wondered about our Christmas tree.

On occasion, two dancers in improvised nursing outfits, carrying salad servers, would demand entrance to my boudoir and declare they were there to give me an internal examination.

I spent almost a year laughing, taking French lessons and shopping for furnishing materials in Liberty’s department store, directly opposite the stage door.

Of course, there were heart-stopping moments. There was a serious panic when Uncle Arthur said a huge pane of glass in the back kitchen of the cottage had cracked from side to side like the Lady of Shalott’s mirror. Jim Thomas, his best mate and neighbour, came round at once to find it was only the fine silver trail of a mountaineering slug.

We had arranged between us a date for certain items of furniture to be moved from manse to cottage in preparation for the final push. In the afternoon Mother rang.

‘PHYLLIDA!’ she shouted. ‘We are being pushed out of the house. They’ve taken away all the furniture. I got them to bring it back immediately.’

I explained.

She was mortified.

I rang the helpful local remover to apologise. He was very understanding and repeated the procedure. Well, he’d known Mother for years.

I had booked my best mate Mildew for my ‘week away’, and we flew up, hired a small car, filled it with food, cleaning materials and petrol, and planned our tactics. Tactful tactics.

Mother had plans to make presents of various items lurking among the piles of ‘stuff’ in the morning room. She was particularly keen to give all the old mattresses to her favourite people. ‘Jock and Alistair would love one,’ she said. She was adamant. Mildew persuaded her to relinquish the idea because they were stained with blood and pee. That did it.

We borrowed ‘the blue van’ and made quite a few alarming journeys to the dump. Every time I put my foot on the brake a mattress and assorted rubbish fell on our heads and the back door flew open. We secured it with a discarded pair of Uncle Arthur’s trousers.

A plumber had to be called to the cottage urgently as someone had pushed a Sorbo rubber ball down the loo.

There was a young plumber of Lea, Who was plumbing his girl by the sea. Said the lady, ‘Stop plumbing, There’s somebody coming.’ Said the plumber still plumbing, ‘It’s me.’

We did a lot of measuring with an alarming metal tape measure. We ordered shelves, handrails and carpeting for the narrow cottage stairs, and installed ‘daylight’ strip lighting in the kitchen. Frightful, but Mother needed an even light as her glaucoma had raised an ugly eye. Sunlight or spotlights or lamplight blinded and confused her. Mildew got extremely bossy and said Mother needed a white stick to warn people that she was a bit dodgy in the eye department, and she would walk down the middle of the road as if it was hers. Thank goodness she wasn’t deaf and heard the local bus. We tried to paint her walking stick with white gloss, but it didn’t take on the varnish, so Mildew wrapped it round with white Fablon, like a bandaged leg. Not elegant, but serviceable, and Mother was charmed. I think.

Mildew’s gift for creative bullying was such a help. We were to get up at six thirty sharp, no breakfast, so we’d get through the lists we’d made at midnight.

The weather, as so often round Easter time, was glorious and sometimes we sat at the cottage against the warm wall of the outside loo, drinking tea, picking dirt out of our fingernails and discussing battle plans.

It was all those books, the china cupboards, the drawers of odd clothing, and the boxes to be marked up. What was to go in the first lot, and what was to be left till last, and would they come in time to mend the heater in the hall, which ought to be on now? We hadn’t enough labels.

And we should arrange food and the fridge, I thought. Mother boiled a wine cork with the potatoes yesterday. Her poor eyes were a bit like Grannie’s were – she couldn’t judge distance accurately. Grannie used to wave her little paws about near objects of interest, like cakes, and leave her footprints on the icing, and Ma was now missing her target as she made tentative efforts to help, a little like a polite child playing blind man’s buff. Mildew said I must learn to put things back exactly where I found them, however odd the place might seem, and I wasn’t to get ‘creative with the cutlery’.

Uncle Arthur wasn’t loving this bit but he loved Mildew and sometimes put his hand up to stroke her cheek. He never did that to me. He said he’d ‘just like to know what’s going on’.

Poor Uncle Arthur. I think I killed him.