Читать книгу Inquisitor Dreams - Phyllis Ann Karr - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

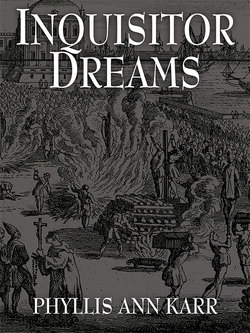

ОглавлениеChapter 7

San Juan de Calamocha

“Here.” Fra Guillaume handed Don Felipe a small book, crudely bound between two separate pieces of boiled leather. “This gives us our present work.”

Taking his seat in the old inquisitor’s tiny study closet (cushioned and comfortable, but barely large enough for two small chairs, a desk, and, in cold weather, a brazier), the young Ordinary opened the volume and found himself gazing at a picture, drawn clumsily but with obvious energy, of two humanlike figures and many bare trees against a darkly diapered sky. One figure, in russet cloak, had his back to the reader. The other was a monstrous, grinning creature like some misshapen ape, with oversized tusks from which poured lines of as bright a red, no doubt, as the young artist had had at hand.

Beneath this illustration were several lines of text, neither as straight nor as even as they might have been; and the wide margins were filled on all sides with scrolling vines and fanciful flowers.

Every page was so illuminated, with illustrations of bloody vigor and demons or grotesque beasts frequently peering through the marginal vinework. Don Felipe read:

Through the dark wood I wandered, lost and alone, when one came and grabbed me by the shoulder. He had a face of great ugliness, but his smile was pleasant, although his fangs dripped blood.

“Who are you?” I cried in my fear.

“I am Arazel,” he said. “I am one of the fallen angels, and you are a sinful man. Together, let us work our way back to heaven.”

He led me to a great gate, on which was inscribed, “Abandon hope, everyone who enters here.” When I read this, I held back in fear, but he pulled me on, saying, “That means to abandon all hope of ever again enjoying your sins.”

We entered, and came to a great, empty, black plain, full of nothing. “What is this place?” I cried, and he answered, “Once it was crowded with poor sinners and fallen angels, but they have all worked their way up to higher regions.”

We went on, and came to a great black lake of burning pitch. Naked men were pushing hairy demons into the smoking pitch and holding them beneath the surface with big dung-forks.

“What is this place?” I cried, and Arazel said, “The first duty of damned souls, whether angels or humans, is to hurt. Their second duty is to be hurt.”

He handed me a dung-fork and said, “Here. You must push me in and hold me down for seven years.” I protested, “But why? You have never hurt me, and I have no wish to hurt you. Besides, it would add still more to the number of my sins.” He answered, “It will not add to the number of your sins, because punishing sinners is holy work. But we fallen angels belong to a higher order of creation than you mortal humans, and moreover we fell before your father Adam was made. Therefore those of us who still remain on this level are closer to heaven than those of you who are still here, and it is your duty to hurt me, and mine to suffer. Now lose no more time, for while we have talked, half a year has passed, and you must hold me down that much longer.”

Thus admonished, I pushed him in, and held him down beneath the surface of bubbling pitch. When it filled up his eyes and ears and nose and mouth, he choked and struggled, and he struggled so hard he got his neck out from between the tines of the dung-fork, so I had to stab it down through his chest and stomach, so his blood bubbled up and made dark red circles on top of the pitch, but I held him down for seven years, although the hard work and hot steam made my sweat pour down, and I could not lift even one hand from the dung-fork to wipe my face.

When seven years were over, I let him up. He blew pitch out of his nose and mouth, grinned at me, and said, “Come.”

I followed him, and we came to a woodland where men and demons stood in pairs, flaying each other with iron rakes.

“What place is this,” I asked, “and who are these?” Arazel answered, “This is the middle ground, and these are humans and fallen angels who have suffered their way this far.”

He got two rakes and gave one to me. “Sinful man,” he said, “it is your turn to suffer. But my turn has not yet come to its end, and here on this higher level we must do it to each other.”

Each rake had seven tines, and the tines were sharper than swords. We raked each other, and our skin peeled up behind the rakes in great curls, and blood ran down to hide our nakedness. People are very naked indeed without their skins. After that, we tore each other’s flesh away and pulled out each other’s entrails until we stood white skeletons in a shambles of our own broken meat. Last, we ate each other’s hearts, and were made whole again.

“Now I am completely purified,” said Arazel. “But you have still to suffer somewhat more. Come.”

I followed, and he led me to a great place of burning. As far as eye could see, in every direction, stakes stood high, with wood piled around them, and some of the piles were green wood, and some were dry, and some were tall, and some were tiny, and some were charcoals. Many of the stakes were empty and waiting, but many more had men and women burning at them. Demons walked through the burning-place, carrying lighted torches.

Arazel said, “In this place are the best mortals and the worst fallen angels, for the mortals have suffered their way here through the lower levels and will go on from here to heaven, but all the better demons have already gone. But these are good enough so all they must do here is light fires. You must find your own stake.”

He bade me farewell and hurried on to heaven, and I saw him no more, but wandered on until I found a stake that seemed fitted to my size. It had a crosspiece, and when I stood with my back to the stake and my arms to the crosspiece, salamanders came and wound themselves around my limbs and body. They held me fast, and a fallen angel came and lit my pyre with his torch.

The dry wood blazed up and seared my skin black and crisp. My eyes boiled and burst, and while they ran in streams down my cheeks and chest, everything looked strange, as if I looked through water. I saw the green wood and charcoals catch fire at my feet, and then I was blind. The salamanders danced in their delight, for fire is their natural home. Their feet cut my flesh, and I heard my blood sizzle in the fire, but not enough to put it out, and I was roasted to ashes.

Then someone came and took me by the hand and led me on farther. There were sweet breezes, and they restored my body to me. When I could see again, I beheld a fair plain all around, as far as eye could see, and flowers bloomed, and birds sang, but still there was wailing and gnashing of teeth.

Then I saw my new guide, and he was a man, but very ugly. “Who are you?” I asked. He said, “I am King Herod, who was never baptized, and was very wicked besides, and killed all the babies of Bethlehem, and so I am still here in the lowest room of limbo.”

I looked around again, and everywhere I saw people racking other people on ladders. “Who are these?” I cried.

He said, “Fallen angels are a higher order of creation than mortal men and women. Even so, baptized souls are a higher order than unbaptized souls. Here, we unbaptized must torture those of you baptized who still remain.”

He summoned two others, who were Cain and Goliath, and together they bound me into a ladder so that my limbs and body were woven under and over its rungs, and the rungs were heavy and sharp. Then they bound strong ropes around my wrists and ankles, and Goliath slowly pulled at my ankles while Cain and King Herod slowly pulled at my wrists, until both my body and the ladder were lifted high off the ground, and blood ran down from every place the rungs cut into my flesh, and all my bones were broken.

Then they pulled me out of the ladder, like pulling one thread from woven cloth, and laid me on the flowery grasses, and sat and talked with me of their great desire to be baptized, until I was whole again and could go on.

Then all three of them bowed to me, because now I was a blessed soul. And Cain and Goliath clasped King Herod by the hands and clapped his shoulders, because in death we are all equals, and wished him happiness, for that now he was sufficiently purified to go on with me. We went on, and crossed a wide, quick-flowing stream, into another flowery meadow, where more birds sang and the air was sweeter than incense.

In that place were ladders laid out on trestles everywhere, and countless people bound all on top of the ladders, while other people gave them the water torture. “What place is this?” I asked, and King Herod answered me, “Here is where we unbaptized receive our baptism, and because we received it not in life, here we must receive it interiorly. But they who give it are the worst of the baptized, who are not yet ready to enter the third heaven, so you have nothing else to do.”

I watched, and Judas and Ganelon came and stripped King Herod and laid him on a ladder and bound him tight. Then Judas got a great bellows filled with clear, clean water and pushed it down his throat, and Ganelon got a great bellows filled with clear, clean water and pushed it up his buttocks, and then both of them squeezed their bellows slowly, and King Herod swelled up like a bladder, and finally burst, and clear water mingled with blood sprayed over everything like a fountain.

Then they unbound his arms and legs, and his head smiled up and said to me, “Now am I well and truly baptized, and as soon as I am healed from my baptism, I must return to the first heaven and there suffer for my own sins until I am purified, but you must go on at once to the third heaven.”

So I went on and entered the third heaven, but of what I saw there, tongue may not speak, only that it was glory and happiness beyond measure.

Here ends the vision of

San Juan de Calamocha

which he dreamed in

the eleventh year

of his age. AD

MCCCCLXXVI.

“It is a great pity,” Don Felipe pronounced on coming to the end, “that this little work is so riddled with heretical fancies. Put it into poetry, and in certain passages it might almost be worthy of Dante, were it not for the manner in which it implies that between Hell and Purgatory, or Limbo and Heaven, there is no fundamental difference, but only measures of degree, and that salvation is freely available to the unbaptized after death, and even to fallen angels.”

Fra Guillaume nodded, smiling. “It would be a very pretty work, if it were not heresy.”

“Is the author truly in his eleventh year?”

“Or twelfth.”

“How has he come by Saint Paul’s description of the Third Heaven, of which mortal tongue may not speak?”

“Most likely from some wholesome sermon. His father testifies that the boy always pays close attention to every sermon he hears. Which is of course commendable in itself.” The inquisitor’s voice grew more somber. “It is a troubling case. The boy’s name is not properly Juan, but Mehmoud. He himself has never been baptized, but it appears that he likes to call himself after his father or, perhaps, the Evangelist or another Saint John. His father is Juan Maria Delgado—formerly Fazoud Aben Fazoud—of Calamocha, who accepted the holy Faith into his heart and was baptized, along with his wife and his children by her, six years ago. Our young author, however, was Juan Maria’s son by his concubine. Juan Maria has ceased to cohabit with her as his wife, and now she lives beneath his roof as sister only. Alas, he made it a condition of his own Baptism that, having been put away, his former concubine must have the choice whether or not to accept Baptism for herself and the children she bore him, of whom Mehmoud is the eldest living. Whether rightly or not…I seem to recall making some formal protest when the case first came to my attention…this condition was granted them, and the lady chose to remain unbaptized, along with her son and daughter.”

Don Felipe studied the old man to whom the bishop had assigned him as Ordinary. Elsewhere, the episcopal courts might contend hotly with the inquisitorial as to which should judge heretics, but here in the diocese of Daroca, bishop and inquisitor seemed to vie with each other only in laxity. Thus far, the young priest’s duties as his bishop’s representative to the Inquisition had proved more social than onerous. At the same time, the mild old French Dominican seemed never entirely to have accustomed himself, even after decades of living and working on this side of the Pyrenees, to the free relationships among Christian, Jew, and Moslem that had existed in Spain for centuries, and still continued to exist, in friendly pockets, even despite the terrible riots and massacres of Jews in great cities not quite a century ago, and the current Holy War into which the Castilian queen had drawn her kingly husband of Aragon against the Moors of Karnattah.

“If the author of this ‘Vision’ remains unbaptized,” Don Felipe pointed out, wondering that Fra Guillaume had not commented further on this point himself, “then his case belongs to no Catholic court, neither yours nor his Reverence the bishop’s, to judge.”

“That would be very true, were it not a case also of proselytizing. This manuscript was found in the possession of one of our lad’s little playmates, Béatrix Cabaza, the child of a fine Old Christian family. It was her mother who brought it to Juan Maria, and he, being no longer Moor but sincere Catholic, wisely chose the Holy Inquisition as that authority to whom the matter must be reported.” Fra Guillaume sighed. He would clearly rather have been dozing in the sun with some holy book resting open on his lap.

“What, then, are we to do, my brother?” Don Felipe awaited the answer in some suspense. Heretical the book certainly was; yet its author, while undeniably of the age of reason and obviously well educated, was still of tender years and, being unbaptized, might remain unaware that his work was anything more than a diverting romance drawn upon spiritual rather than secular themes.

After another sigh, Fra Guillaume replied, “The boy has been in the cell since yesterday afternoon, when his father brought him to me. Juan Maria, having passed the night, as I believe, with a business acquaintance in this town, has been waiting outside the tribunal since early morning.”

Don Felipe nodded. “I believe I noticed him. A tall man of middle age, well dressed, with somewhat shaggy black brows?”

“That was he. A good man. I regret that I have not some sort of vestibule where he might wait with greater comfort.” At one time, the Inquisition’s Daroca tribunal had been housed in a monastery on the outskirts of the city; but for one reason or another it had been moved several times, to end, some years ago, in a few rooms beneath the arcade of a wealthy merchant’s home, flanked by shops to right and left. “I had thought,” Fra Guillaume went on, “that this matter might be disposed of with the minimum of formality. If the bishop’s office makes no objection, we might proceed as far as a little gentle application of the first degree, and manage to dismiss our young culprit back into his father’s custody as early as tomorrow.”

By “the first degree,” Fra Guillaume meant the threat of torture. This being in itself a form of torture, it ought not, formally speaking, be applied except in last resort, after careful consultation and deliberation. Already in a few months, however, Don Felipe had come to trust the old inquisitor as a man who would always choose the smoothest and least painful course for all concerned, who would take no step unless he judged that thereby he could end the matter as quickly and satisfactorily as possible. Better, surely, that the boy be subjected to the threat and returned home at once, than that he should remain weeks in prison, costing all the labor of a full inquisitorial investigation for what was, after all, little more than the childish romance of an unbaptized brain, based on misinterpretation of Christian doctrine.

The Ordinary nodded. “His Reverence’s office will make no objection, even at this stage, to some judicious use of the first degree.”

“Then I think,” said Fra Guillaume, “that we may as well proceed.”

They repaired to the audience chamber and Fra Guillaume sent his one assistant to fetch the prisoner. Fra Guillaume’s assistant was a lay brother even older and slower than his master; the Inquisition was to call upon the bishop’s resources should need arise, but as far as Don Felipe could learn the need had not arisen in this diocese for years. The young priest had time while waiting to ponder whether or not the rolls of dust round the edges of the floor had grown measurably larger since his last visit.

Once, the Inquisition had been a weapon to strike fear into the armies of Satan. The Dominicans still boasted of how, with God’s help, they had stamped out the deadly peril of Albigensianism some two centuries and a half ago. How had the proud army decayed! At least here in Aragon…and only in Aragon, of all the kingdoms of Spain, had the Inquisition ever been planted.

Some attempt had been made to return Fra Guillaume’s present audience chamber to the fabled black-and-white austerity of earlier ages; but here and there the black draperies were torn or moth-eaten, and in many places the white paint was already worn away, leaving the former bright colors of murals and floor tiles showing through, while the long table and chairs were at best only dark brown.

Fra Guillaume’s lay brother brought young Mehmoud in and gave him a three-legged stool to sit on before the tribunal, then shuffled back to stand at the door, his hands folded into the sleeves of his coarse habit.

Looking around guardedly, with many apprehensive glances across the table at Fra Guillaume and Don Felipe, the young offender adjusted the position of his stool three or four times, hitching it minutely here and there across the painted tiles, until the inquisitor sternly bade him cease, when he finally sat still, head lowered.

“Well, Mehmoud,” the inquisitor began, almost genially, “what have you to confess today?”

“Juan,” the boy mumbled. “My name is Juan.”

“If you were baptized, it might be Juan. Until then, it is Mehmoud.”

Mehmoud lifted his head and stared back, anger struggling in his face with fear. “Then I have nothing to confess! And…and if I did…how could you listen to it?”

Don Felipe shut his eyes, grateful that the boy was directing his stare principally at Fra Guillaume. The image had flashed unbidden into the Ordinary’s mind of the boy Ihesu debating in the Temple with the rabbis of Jerusalem. Even so must the divine Child have appeared, dark-eyed and olive-skinned—all paintings and illuminations to the contrary, Felipe de Alhama de Karnattah was aware what the Messiah’s true race would have been. Even so might the boy Ihesu have lifted one brown hand to push a lock of straight black hair away from His high forehead.

Yet surely the holy face of Ihesu would not have been stained, at this age of His earthly life, with tears. Surely neither His hand nor His voice would have trembled before His mortal elders. And then it came to Don Felipe that whom young Mehmoud really reminded him of was his own boyhood friend Hamet. Flooded with relief, he opened his eyes and looked again at the author of the heretical Purgatorio.

“It is not a question,” Fra Guillaume was saying, “of the holy sacrament, but rather one of practical jurisprudence. Mehmoud Aben Fazoud, confess your crime!”

“My…my father is Juan Maria Delgado de Calamocha! At least I am Mehmoud Delgado de Calamocha!”

“He was not of that name when you were born. As for you, you have still the name you had then, in its entirety. Now, confess.”

“It is not…If it were sinful to write visions of…of…”

“Boy,” the inquisitor said harshly, “have you any conception of how it would feel in reality, to be tied to the ladder, made to swallow whole jugsful of water, dipped in boiling pitch, and so forth? Have you any idea what a single real beating with rods would be, in comparison with all these agonies when simply put in a story?”

Mehmoud seemed to shrink into himself. Face writhing as if he already felt the blows, he protested, “I put my name to it! What…what else…?”

“Confess your crime,” Fra Guillaume repeated.

“Mehmoud Aben Fazoud, then! Is that what you want? Not Juan de Calamocha, but Mehmoud Aben Fazoud de Calamocha! It is mine, I wrote it, I do not hide that I wrote it, I have never hidden that I wrote it!”

“Holy Church will rejoice on the day she can welcome you as another Juan in baptized truth,” said Fra Guillaume, “but today search your conscience further.”

“Is it…because I used ‘San’? Is that it, my lords? I should not have called myself ‘San’—I renounce ‘San’!”

“Good.” The Dominican nodded. “It is not for any of us to sanctify ourselves in this earthly life, but only for Holy Mother Church to bestow that title, upon those whom she finds worthy of it, after their earthly deaths. But is this all that you can find it in your heart to confess this day?”

“What else? Ah, God! Is there still something else?”

Fra Guillaume sat and gazed somberly at the boy, beating one gnarled old hand against the other with regular if seemingly unthinking strokes. Don Felipe found his brain repeating the Gloria Patri. It had scarcely reached “et Spiritui Sancto” when Mehmoud asked again, in a desperate voice, “Can there still be something else?”

The young priest could stand no more. Dangerous though it was even to hint at the exact nature of any accusation in the hearing of accused parties, lest in their eagerness they fall into the sin of bearing false witness against themselves, he guessed that this boy sincerely did not understand wherein lay the one crime for which the Inquisition could rightfully try him. Turning to Fra Guillaume, Don Felipe said carefully, “Perhaps we should turn our attention to the person actually found in possession of the book.”

“No!” Mehmoud half wailed, falling from his stool to kneel before them. “My lords, it was my fault—all mine! I gave it to her! She cannot even read yet—she only liked the pictures!”

To Don Felipe’s eyes—though he doubted young Mehmoud would notice it, head down and weeping as he was—Fra Guillaume’s whole being relaxed. Later, inquisitor might take Ordinary to task for his words; but not in front of the boy. Indeed, Felipe suspected, Fra Guillaume was secretly much relieved to have had the hint dropped, but not by himself. For now, he said only, “The sinner has made full confession at last. Some hours we will need for consultation as to his sentence and penance; but I think, with his Reverence the bishop’s blessing, we might finish this process tomorrow. Meanwhile,” he added to his lay brother, with a gentle nod toward the prisoner, “let him be returned to his cell, and see that he has broth, good bread, and I think, a little good wine.”

After the lay brother had led Mehmoud away, not unkindly, Fra Guillaume turned his gaze full on Don Felipe and said, “With all respect, my honored friend, do you understand what it was that you did just now?”

“With deepest regrets, good brother, I do. And I pray that God and our Lady may preserve me from ever falling into such error again.”

“Good. Then we need say no more on that subject.” Nodding, the old Dominican put his hands upon the table as if to push himself up to his feet.

“What of the other child?” Don Felipe asked. “Béatrix Cabaza, was it not?”

“I hardly think we need worry about her,” Fra Guillaume answered like a man who had already weighed the matter to a satisfactory conclusion in his own mind. “That her parents brought the book to its author’s father shows their concern for their daughter’s spiritual welfare. Moreover, by the boy’s own testimony, young Béatrix cannot yet read, and I think that the pictures alone could do her soul no injury. Without reading their names, she could not even know who King Herod and the others are meant to be.”

Unless, Don Felipe thought, Mehmoud had told her his story. Close on that thought came another: that the boy had not actually named Béatrix Cabaza; that he might have made more copies than one, and passed them around to more playfellows than one.

Nevertheless, if the Inquisition itself, in the person of its experienced servant, chose not to pursue the question of how many youthful disciples or even accomplices Mehmoud’s infant heresy might have gained in his town of Calamocha, who was a very young Ordinary to teach him his venerable business? Truth to tell, if Fra Guillaume preferred dozing in the sun with a spiritual book to rooting out possible juvenile heretics, so did Don Felipe.

They returned to Fra Guillaume’s study and settled Mehmoud’s penance over one or two glasses of sherry. Or, more accurately, the inquisitor imparted what he had already decided, and the Ordinary approved it: a reprimand and warning, to be administered privately tomorrow morning in the audience chamber; burning the book in the author’s sight—both churchmen regretted this necessity, but Fra Guillaume believed that, with the permission of the house’s owner, it could be accomplished on a brazier in the courtyard; and requiring the boy to abstain from all meat for a period of two months. Since Mehmoud was unbaptized, Fra Guillaume judged that such penances as prayers and pilgrimages could hardly be imposed. He had, however, an old manuscript volume of the Tractatus de purgatoria Sancti Patricii, which he would loan to Juan Maria Delgado de Calamocha on condition that Mehmoud make two illustrated copies, one to keep and one to return along with the parent volume.

“The Purgatory of Saint Patrick,” Don Felipe mused aloud, turning its pages. “I think I have heard somewhat of this place. In Ireland, is it not?”

Fra Guillaume nodded. “At the very edge of the world. Had our Lord seen fit to put it in some less outlandish place, with fewer wild natives and discomforts of the journey, it is a pilgrimage I might have wished one day to undertake for myself.”