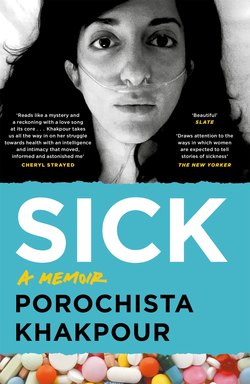

Читать книгу Sick - Porochista Khakpour - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

IRAN AND LOS ANGELES

The one thing I do know: I have been sick my whole life. I don’t remember a time when I wasn’t in some sort of physical pain or mental pain, but usually both.

I was born in Tehran in 1978, infant of the Islamic Revolution and toddler of the Iran-Iraq War. Like many Iranians of their educated, progressive, Western-friendly upper class, my parents did not last there. My first memories are of pure anxiety, buses and trains and planes with my two parents, who I was cognizant were just two clueless beings—a twenty-six-year-old, a thirty-three-year-old, both often in a panic, occasionally in tears. Furiously I told stories to distract them, books the only toys we could fit into our two suitcases. Whenever I could, I took pen to paper and drew images and had my father dictate my narrative. It was not much, but it was something; storytelling from my early childhood was a way to survive things. Meanwhile I tried to ignore everything in the air—hot air balloons, helicopters, later fireworks and light displays—that resembled air raids and bomb sirens. I knew to hide my trauma, at least until we found a home.

This isn’t your home, my father would say when we got to the US. We’ll be going home again one day soon.

He said that for three decades. Now in the fourth, he likely still says it.

Years later several doctors, and also my own parents after they’d read some study, told me that if a child is exposed to significant trauma in the first three years of their life, they could have significant psychological repercussions later in life. PTSD. The brain of a child develops at high speeds, those first few years a time of rapid development. And as their brain develops, so do their emotions.

No one who knows this study has ever let me forget this fact.

Like most Iranians we ended up in Tehrangeles—almost. The portmanteau referred to the enclave in the West Side of Los Angeles that had become home to an Iranian diaspora, mostly refugees on political asylum like us, but also many other wealthy Iranians who simply felt at home in the Southern California of luxury and hedonism, far before a siege on their homeland would force them out. But while we’d spend weekends there at various kebab houses, driving around Rodeo Drive and gaping at rich Iranians flaunting their nose jobs and carrying designer shopping bags, and going on long rides to see their McMansions, we never lived there. We were forty-five minutes southeast, inland in the East Side suburbs, from Alhambra and Monty Park to eventually South Pasadena. My parents were no longer crying at least.

And so my father began looking for work, a process that has never quite ended. His accent canceled out his MIT PhD—and this could only mean adjunct professorships with little hope of much more (my father, well into his seventies now, is still adjuncting). At first we were a quick drive from Cal State LA, his first place of employment. It was in the library of that very college that he learned from a librarian of a city called South Pasadena, a place that was expensive if you wanted to buy but affordable if you wanted to rent, and it had an excellent public school system. That was all that mattered to my parents, my future still a thing not ruined in their eyes.

We lived in that greater Los Angeles suburbia from when I was age five through high school, the four of us, two upper-class fallen aristocrat Royalist Iranians, who left everything behind and raised two lower-middle-class children in a tiny apartment in South Pasadena, California. Even during our greatest financial struggles, my parents were too prideful to accept government assistance. My whole family shared a single bathroom and my brother and I shared a bedroom until I was seventeen. While my parents mourned their lack of wealth, all we cared about was the brand of normal that sitcoms, films, and songs of the eighties promised: a sort of oblivious California happy that could cancel out the news and its consistent airing of grievances against our homeland. Iran was never far from the media’s lips, it seemed, and that poured into my home and playground life with equal heaviness.

I love that sad, simple apartment, but it wasn’t until I was much older that I recalled the mold in the bathrooms. The cracks in the ceiling. The peeling paint everywhere. The suitcases in the closet always packed for an emergency, always packed for fleeing, presumably back to Iran. The way we’d have to negotiate lunch money. The times of true poverty that my parents lived in that they thought we couldn’t see.

Decades later Los Angeles would be the only place I would contemplate suicide—not once but twice—the least healthy place in the world for me. In a way, I always felt it. My entire childhood I was sick with one thing or another, always feeling broken in my body. Depression was a constant. It would be many years until I realized that not only did Los Angeles have particularly horrible pollution but that Pasadena was one of the worst—a big bowl of dirty air thanks to car culture plus the mountains, a sponge absorbing all the smog. Good schools, yes, but we had ended up in the worst place for health imaginable—though for my parents, both relatively able-bodied, health never seemed to be much of a factor. No one paused and thought my preferred dinner of two Wienerschnitzel hot dogs or McDonald’s chicken nuggets or KFC buckets was bad. No one stopped me from soda. Nobody asked what I was spending lunch money on, when it became clear I’d be bullied if I put Persian stews or cold kebabs and rice anywhere except in the trash. No one bothered to knock on my door those weekends when I stayed indoors every second, reading and reading and more reading, and writing furiously, still deep in the dream of stories, fully invested in being a “girl author” one day. I had notebooks devoted to plotlines, to vocabulary, to illustrations of my stories. No one bothered to say, That’s nice, kid, but you also need to go outside. While I attempted community center classes in ballet, jazz, tap, gymnastics even, no one told me to stick with it and not to quit, when as usual I realized I did not fit in. The only place I fit in was not quite home but what was within our home: it was the desk, the chair, the pen and paper. It was the only place I felt well.

As a child I had severe ear infections and one that led to near deafness, though I never let on that I knew my hearing was dropping out, and I’d merely guess at what people would say to me. Occasionally I was right. Eventually I had surgery to put a tube in my ear. It was then that I had what I consider my first drug experience—what I used to joke about, but today I do indeed think of as part of early wiring that led me to drugs later in life, or a fascination at least with altered states.

The doctors apparently could not give me enough general anesthesia to put me out during the routine surgery, which resulted in my very lucid hallucinations. I have two memories of the whole ordeal: one is waking up, with surgeons in their green uniforms hovering over me, their movements and sounds ultraslow while behind them in the hospital everything moved in hyperspeed. This was only one of the couple times I woke up midsurgery, when they could not put me out—but the time I remember. The other memory is of afterward, waking up clutching a stuffed animal I didn’t recognize in the waiting room, on my mother’s lap, being told by the doctor that he had never met such a brave child.

“We couldn’t put you to sleep—you didn’t want to go to sleep, brave girl?” he said. “I’ve never seen such a brave girl.”

I remember not understanding, feeling suspicious of the doctor. “What happened to me? What went on in there?”

“We fixed your ear, brave girl,” the doctor said. He clearly could not say my name, something I was already used to by that point.

“I woke up,” I said. “I woke up and saw.”

Nods and chuckles, doctor and mother.

Later in the car I tried to convey to my mother that time had been altered in there, that it had sped up in parts, slowed down in others, and I saw it happen.

“It was the gas,” my mother said. “They gave you a gas to sleep.”

“I was awake,” I said. “I woke up.”

“Yes,” my mother said wearily, “it was a drug. The drug made you see that way.”

In just a few years, when Nancy Reagan and the Just Say No to Drugs slogan was as ubiquitous as Merry Christmas, my mind darted back to this memory—my mother telling me they had put me on drugs, that I had drugs and that they had made me see that way.

The end result of that: I became suspicious of doctors. And I became fascinated by drugs.

I had my own ideas. I tried to steer clear of our family pediatrician who always seemed a bit off to me. I decided the life of the body would be a secret life and that I was in it for the brain anyway. So many books to write, so many to read, so many words to learn. I was determined not to get tested for ESL again, determined to be one of the honors kids, determined to do justice to Mrs. O’Connell, my second-grade teacher who saw my handmade books that we made from the refugee days and onward and said, I’ll bet you will be an author one day. And it was because of her that I agonized over submissions to Highlights for Kids— always rejected—and that I made my father buy all sorts of guidebooks on how to publish kids, all fruitlessly. But I had a work life and there was nothing that was going to get in the way of that, not even the flus and colds I would always get. And not even the tremors.

I never told anyone about the tremors, but that was what I called them, named after that word I had learned that referred to the earthquakes of my new habitat. I was still a few years from experiencing earthquake tremors but always greatly feared them. The first earthquakes I experienced were the ones in the body instead. They always came late at night, when my parents were supposed to be sleeping in the room across a tiny hall from my brother and me, bridged only by the restroom. The tremors always came after I’d listened to my parents for a while, their whispered conversation turning into a whispered sort of yelling and sometimes bangs, what I recognized as the sound of a rattling headboard.

My brother somehow always slept through this. I was always deeply worried and deeply afraid to do anything about it—I could not make it out of my bed and risk being seen as witness to their fights. And my body, as if in cooperation with that notion, didn’t let me. Generally a half hour into it, my entire body would go into a shaking, starting with my legs, a sort of violent involuntary rattling that would stop on its own after a while. Sometimes it felt like hours would go by. Suddenly it would be time to go to school and I had no explanation for why I felt like death. My mother never suspected I was not sleeping, never suspected I was listening to them, never suspected the tremors. Only once, one summer evening, I remember her taking my hands in hers and staring at them in deep concentration.

“What are you doing?” I asked, alarmed.

“Your hands are shaking,” she said. “Why are your hands shaking?”

I shrugged. I had not noticed.

“It’s all the writing,” she said. “You need to stop writing so much. It’s cramping your hands. Take a break.” Later she said that about tennis, piano, pottery, anything I tried to expand myself in, but her jab at writing hurt most because it was the first thing close to a purpose I had found in this new world of ours. I remember feeling furious with that suggestion but knowing better than to fight with her. I would keep writing. At that age I already knew they could only control me so much.

The tremors seemed to fade as I entered my preteens, though that was when I cared less about listening to my parents’ late-night altercations. Walkmans existed and I had convinced my parents to get me a Sony Walkman for Christmas one year, which felt like the greatest invention on earth, especially for someone like me who was so dedicated to a private life. I could listen to things without them interfering. Radio could transport me into all sorts of possibilities, and I was allowed cassette tapes here and there, Madonna, Michael Jackson, Janet Jackson, and Cyndi Lauper. While my father argued they were all obscene, he did not go so far as to stop me.

By my preteen years I was obsessed with late-night radio, where I could learn about what cassettes to buy, and where I could listen to the show Loveline on one of my two favorite stations, KROQ. It was a show on which they’d have a music guest, which is what I pretended I was in it for, but the main point of the show, love and sex advice, was the real allure for me. KROQ must have been where I learned about sex, as it certainly did not come from my parents. So from 11:30 to 1:30 a.m., I could put on my headphones and not disturb my brother across the room, pretending, when my mother tucked my brother in, that I was also deep in sleep, while I was actually learning about STDs, 69ing, spitting and swallowing, orgies and ménage à trois. She never bothered to check the headphones that I wore upside down under the covers. Listening and laughing along with Poorman and Dr. Drew seemed infinitely preferable to listening to the terrifying bickering of my parents. Maybe by that point I had learned nothing too terrible would come of it, nothing worse than the other bad things that seemed to happen in our house anyway.

The next time I remember being very ill also involved entering in and out of consciousness, though not so artificially as when I was drugged for my ear surgery. I was thirteen and it was a Sunday, as the concept of school was looming large, and I had just taken a shower. The shower was a hot one—I’ve always been partial to very hot long showers, especially when given the mammoth ordeal of dealing with my always-tangled, always-frizzy, impossibly thick black hair. But this time, in the fog of the bathroom, as I dried off, I felt strange. I felt both lighter and heavier, like I was being pulled up and down at the same time. My eyesight seemed altered—visuals seemed both brighter and darker, strange shadows jumping in and out, all electric in their tone, nearly metallic in shade. I felt like the life force was being vacuumed out of me, from every opening in my body. I wrapped the towel around me and wandered into the living room and called out to my mother.

“What’s wrong?” she asked absently, engrossed in the television, on her usual love seat perch.

I remember saying simply, “I think I’m fading.”

The sentence did not seem to mean much to her, and so I struggled alone to their bedroom, not mine for some reason. Moments—minutes?—later I was lying on their bed, and my mother was shaking me and speaking rapidly in a panicked high pitch I’d never heard. “What happened?” I asked, as the colors of the room rearranged themselves into normalcy, the sounds falling into their more proper places.

But she was still red in the face and frenzied. “You fainted!” she cried over and over. My father was now at our side and he seemed very upset too. But I was beyond the realm of upset or anxiety. I felt more peaceful than I had in ages. In the days to come, I felt special as a fainter, as if I was a character from another world. It felt like an event to have a condition, especially since I was still months away from getting my period, the affliction that it seemed everyone I knew got to complain about.

This called for me being dragged to our family pediatrician who said it was normal for my age, which disappointed me. But then he brought up the possibility of me carrying smelling salts—which I’d only known from old Victorian epics and period cinema that I had at that point become obsessed with—and I was overjoyed. I eventually got them, but I never got the opportunity to use them. I never again let myself fully pass out—instead, when it came to that intense fading, the light-headedness, after a hot shower and often at malls, I would sit and place my head between my legs as instructed, and I’d always somehow evade it.

I liked that there was danger involved with me, that I was someone people could lose, that I could flirt with some other realm, that I was intensely fragile yet ultimately indestructible. I felt like a crystal ballerina, a porcelain swan, but most of all like a ghost. The haunting metaphor felt actualized in some part of me: a part-ghost at least. I had access to some other world, but I could be in this one too—I told myself that narrative. The narrative I ignored was the one where I should have also realized that it was the first time I got to feel like a woman—and that perhaps ailment was a feature central to that experience, the lack of wholeness one definition of femaleness, or so they would have you think.

When in 2009, almost twenty years after that first fainting incident, Dr. E, an infectious disease specialist who treated my Lyme in Pennsylvania, tried to get my entire history of illness, I recalled all these instances. It interested him, the ear surgery, the tremors, the fainting. He asked me if there was any chance I could have been exposed to ticks, and after much struggling I could only come up with one memory: when I was around six or seven, just a couple of years into our new life in America, my father took my mother and me hiking.

I remembered it being the Angeles Crest Mountains, because I loved the name—back then I digested American words like they were frosted desserts, and anything with “angel” was delicious to me. We were hiking through a forest that seemed unlike much of Los Angeles, and my father said they reminded him of the mountains in Iran. (My father tended to say that about most mountains.) We got to an area with a sign, a wood sign that I still vividly remember as painted brown with a very friendly-seeming yellow font that announced LYME DISEASE • BEWARE OF TICKS and some other fine print under it that I did not read. I remembered it because of the word Lyme. I was new to English and I had become obsessed with spelling, and I turned to my father and said, “They spelled lime wrong, didn’t they?” And he had stared at the sign long and hard and my mother and him muttered back and forth and then shrugged off their worry, as they usually did, like people who had seen it all long ago. Ticks were the least of their concerns.

I remembered the Farsi word they used: kaneh. Which referred to a pest of some sort and is a sort of insult you could use for someone, someone more than possessed by a bite, someone who has lost it. My father explained it was a disease one could get from bug bites and I remembered thinking bugs liked to bite me—every summer my legs showcased constellations of mosquito nibbles. And then, as children do, I forgot all about it and we hiked. It’s one of my few memories of hiking with my family—the Khakpours were seldom the outdoorsy sort. And it was eighties Los Angeles, when hiking at some altitude was the only way to get away from the thick brown veil of smog that covered the city more often than not.

It was only years later when a man who loved me took me hiking in that same area that I again saw the sign—this time I was with diagnosis, sick and shaking—and I thought back to telling Dr. E the story, who saw it as a highly probable origin story. And I thought back to the event itself and the calm of my parents and my own calm, probably thinking how on earth could a bite from an insect do damage.

Of all the things that could do damage—revolution, war, poverty in this new land—why would anyone think of a kaneh?