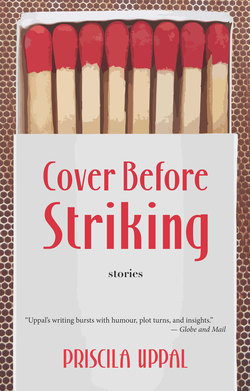

Читать книгу Cover Before Striking - Priscila Uppal - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

The Boy Next Door

ОглавлениеIf I told you my mother ran away with the boy next door, I wouldn’t be lying. Except that he was a man, not a boy. And a priest, not my father. But he did live next door. And my mother did run away with him. Although it was more like walking, very calmly, an organized exodus.

I had thought my mother’s keen interest in church was a direction of her energies toward my soul. My first confession was coming up in the next few months and as with any big Catholic event I believed she wanted to make sure I would perform it properly in front of the neighbourhood. She had been a regular churchgoer before then and wrote for Our Faith, the church bulletin, articles about bake sales and ads for seniors who were looking for companions to take them grocery shopping. She wrote her pieces at night, pulling out the extension of the dining-room table, laying her typewriter on top. She was a valued member of the congregation and we attended every Sunday, sprinkling ourselves with holy water and kneeling on the smooth pine floor. Then, over the course of that spring, she started to take on extra parish duties: helping clean the pews, baking cookies for the prayer group and the choir, passing out flyers, and arranging rummage sales. She didn’t seem to pray more that I knew, but she started spending more time in church than at home. I assumed Father Marcus approved of her as a good neighbour, or concluded that she had felt the good grace of God between the hedges separating our houses from one another.

Father Marcus was not the pastor. That was Father Brown. He had been the main pastor at Resurrection for thirty years and was well-liked by the parishioners, especially the older ones, who seemed to see him as a direct link to the heavens. The other priest had only been preaching for two years before he left for another town, to be closer to his family we were told. His job was to take over the lighter times of worship and help the children at my school with catechism. Father Marcus replaced him and moved next door because Father Brown liked living in the church. He had gotten used to it, though a church widow had died and left her house for him. That’s how the story goes and how he came to live beside us. I didn’t mind. He was young and seemed nice, and he countered Father Brown’s solemn hymns, like “The Lord is My Shepherd” and “Lamb of God,” which we would sing as if our throats were made of shame, with lively psalms of joy like “He is the One” and “We Are the Children.” Sometimes I had to restrain myself from clapping as I sang these new songs, and besides, he wore only his collar and would play murder ball with the boys at recess and hopscotch with the girls. He spent a lot of time outside, his skin tanned and taut, his legs flexible for the sports, with hair dark and even without a touch of grey. Before school, if he was around, he would turn the end of my skipping rope on the driveway so I could jump if none of my friends were outside. He had even learned some of our songs, “Steamboat Sally” and the “Big Bad Wolf,” and his strong voice slammed down with every slap of the rope on tar. He carried home lots of food, plastic bags hanging like extensions from his body. Loved to cook. If our kitchen window was open we could smell his peppers and tomatoes, chicken and beef, frying or steaming, turning colour. After Communion, which tasted exactly the same to me as biting the rim off a Styrofoam cup, was the only time the church was full of food. Mostly sweets, cakes and tarts and watery tea I would sip while waiting for my mother. The smell of the church basement snacking was sterile, nothing like the aroma from next door that stung the eyes and rose in the air, inviting.

Once confession lessons started, it was another story. I tried to think of what sins I could tell Father Marcus, and every time I saw him I was reminded of the secrets he would know about me. I played farther away from the house, thinking God was too close to my thoughts before I could work them out, figure out how to explain them properly. He could watch my whole family from his backyard while we swam or barbecued or he worked on his vegetable garden, his legs bending like grass, straight-edged and graceful, pulling up carrots and cucumbers in his gloved hands. He wore white shorts on truly hot days, and I was amazed by the thick dark hair that curled all over his legs, forming a kind of coat around him, making his almost black eyes seem even more piercing. I wondered if he was keeping tabs on sins I didn’t remember, some commandment I had violated like not honouring my father and mother, or lying. I wanted to ask him if some sins were more forgivable than others, or whether there were any sins that couldn’t be forgiven. On a tour of the confessionals, those boxes painted like small houses and without the stained-glass pictures as on the rest of the church, I noticed the screen was thin like the one on our gazebo. I could tell it was Father Marcus, so I’m sure he could tell it was me inside. I wanted to change what he knew about me, imagining what joy there could be in shocking him, repeating dirty words or telling him I sometimes wished my parents were dead. I felt tantalized at the whim of hearing him gasp, afraid for a moment of the girl next door who skipped in the mornings, that he could think I was dangerous.

At the same time, I had begun to find out about kissing. I knew about it already, seen my mom kiss my dad quickly on the lips, watched longer full-mouthed kisses on television, but had never felt what the fuss was about. You would need to confess kissing at my age, I knew. God did not approve of us kissing, but at recess we would sneak behind the monkey bars to the brick wall and play a game. You would ask for a kiss, and then everyone else would choose who was supposed to kiss you. You would close your eyes and wait until they had decided. Silently, someone would approach, the heat of their mouth close as the silence of expectation rose, and press down. The rule was you couldn’t open your eyes and couldn’t tell who had been delegated with the role of kisser, but we did, of course. And some kisses were better than others, I understood that, and sometimes they weren’t from the boy you liked.

The kissing game had been a source of prayer for me. I asked God to forgive my lips of their sins and to wash me clean before I went to bed at night. I would tell Him I promised to try my best not to do it again until I was older. I would shiver, imagining the dark booth of the confessional awaiting the secrets of all those backdoor kisses in the broad daylight, where anyone who went behind the wall could have witnessed the game. My mom had put me in the choir and I would sing “Ave Maria” and “Blessed Be the Lord” in the front row, my clean, pressed, white dress covering my body to my toes, and think of that brick wall that smelled of urine and bubble gum, wondering if the altar boys (some who I knew) would tell Father Marcus or Father Brown about the one time I let them look up my dress on a dare. I would blush all through Mass, trying not to look any of the parishioners in the face. I kept my eyes glued to the arched ceiling as the blinding light floated down upon our heads. My father said he thought I had a little crush on Father Marcus. I told him it was on God.

In school we listened to lectures on baptism and Christ’s death, tales of thorns and nails, hunger and rotten kisses. If He had already died for our sins, what was the point of confessing? I wanted to ask. But no one asked questions in class. We took notes and stared at the crucifix nailed to the border of the blackboard. A naked man we were supposed to love spread for all of us to see. It was after class that I could sometimes dig up the nerve to ask questions. Especially if I was sitting outside and Father Marcus happened to pass by and ask how I was, then I would have something ready for him to clarify, like why Peter falling asleep was such a bad thing, or how come Mary was God’s bride and not Jesus’s mother? He would sit down with me on the concrete steps, his dark eyebrows raised in earnest, and explain. I wondered about Christ up on that cross, and what people had wanted from him.

“Why did they have to kill him naked?” I asked, tentative about saying the word naked to a priest.

“They wanted to humiliate him,” Father Marcus replied.

“Oh.”

“You seem confused.”

“I thought maybe they were curious,” I whispered.

Father Marcus stroked his collar with his fingers. “Maybe they were. Israel is a very hot country.”

I made a habit of going next door without asking. Father Marcus was always willing to receive me, even if he was cooking. I would help him chop zucchini, or slice crumbly white cheese we didn’t have at home, and he would sing hymns or teach me recipes; how long to boil the water, how to know how much paprika to add. He could even make roses out of radishes, his fingers quick and selective, and I would write some of his lessons down on a pad of yellow paper he kept by the phone. He told me my mother would appreciate it. She and my father would eat the new dishes (if we were missing a mysteriously spelled spice, Father Marcus would provide it in a tiny plastic bag) and my father would read his newspaper at the table, mumbling between chewings how good my mom could cook. Later the hot spices would send him up to bed to toss and turn in his blankets or hold his cramping belly in the bathroom. Then he said they gave him bad dreams, never had the stomach for foreign cooking. The meals had strange names, Portuguese names I didn’t know how to pronounce, from Brazil, where Father Marcus came from. One day I found Brazil on the map pinned to our classroom bulletin board. Although it wasn’t as large as Canada, I was sure it contained many more spices. I would flail my hands around my mouth from the heat at first, but gradually, with practice, I could place the spices directly onto my tongue without flinching.

I had been practising the harmony section of “The Lord Is My Shepherd” when I noticed the forgotten casserole my mom had baked for Father Marcus. She had spent all day in the kitchen breaking eggs and soaking vegetables, pushing me gently into other rooms to practise without disturbing her. I clasped the heavy dish in my hands, raking in the smell of sweet tomatoes, zucchini, and beef, and strolled up his stairs. I noticed the door was slightly ajar and cupped my sole around it, kicking back a little. I wandered through his living room where black-and-white pictures of dark-haired people in light clothes hung alongside coloured paintings of the Virgin and Jesus. I had pointed to those pictures on one occasion and asked him who they were. He said he didn’t know, that they were just decoration, and he looked a little sad, his lips curling around the edges. I was on my way to the kitchen when I saw my mother collapsed in the arms of Father Marcus, giving him a TV kiss, a long one, part of her yellow silk blouse hanging off her shoulder, her light brown hair curled around her neck, her lips an offering. I nearly dropped the casserole, and then clung on to it like a stuffed animal, biting the Saran Wrap. Father Marcus opened his eyes and saw me there. He didn’t even flinch, closing one eye, his mouth moving toward her neck, and I was glad that my mother never turned around. I sneaked out the door, casserole in hand, shaking. He caught me before I could get through my own front door.

“Come here,” he said calmly, his heavy-lidded eyes downcast.

I couldn’t disobey a priest, but I wanted to. I was going to cry and didn’t want him to know. When I looked at his face I saw my mother’s lips pressing on him, the same lips that she would blot thick with “kissing-red” lipstick, as a joke, because I loved the name, and smack my cheeks. He took the casserole out of my hands, had to give a forceful tug on it if I remember correctly, and laid it on the bottom stair like a loose brick. I had already started to cry, turning away from him, wrapping my arms around my stomach.

“It’s all right. Don’t worry.”

He was reaching out his hand for me to hold, but I put mine behind my back, even though I wanted to wipe my face free of the tears.

“You saw us, didn’t you, dear.”

I nodded.

“Me and your mom.”

I nodded again and kicked at the stone stairs.

“It’s natural for your mom and I to kiss. We love each other, you see.”

I knew priests were supposed to love everyone, but the thought of my mother’s arms wrapped around him, touching his body. His body.

“I didn’t know priests had lips!” I yelped and slid around his legs on the steps, heaving, trying to take in enough air to keep listening.

“Priests have a lot of things,” he said. “We’re just like other people.”

“No you’re not.” That I was sure of.

“Not entirely … we cook better.”

I pressed my face against his chest for a moment and he went in to get me a washcloth.

That night I ran straight up to my room and faked a stomach ache so as not to eat dinner with my mom and dad. My dad just accepted it and didn’t come up to check on me, his spoon already dug deep into another casserole. My mother did. I don’t think Father Marcus told her what I saw, but she came to tell me that in a couple days we would be leaving when my father left for work. We were going to fly in a plane and have a vacation. I started to cry again. She brought me ginger ale for my tummy, and told me we would all be happy, and not to tell Dad. That wasn’t difficult.

On the Tuesday we packed quickly, just as she said we would, right after Dad left for work. We took only “necessities,” as she called them, and “favourites.” For me this included a few clothes, a red-haired beanbag doll I’d had since I was a baby, and a toothbrush. My mother also took very little, her purse and some clothes, saying we would buy new things, but that night she had been up late typing her last letter for the church bulletin and I figured she didn’t pack because she was pretty tired. On a yellow piece of paper I wrote “I’ll miss you” and shoved it in my father’s sock drawer at the bottom. He never really liked to travel.

Father Marcus arrived with two suitcases and passports for all of us. A week earlier, as a surprise, my mom had taken me to a photo booth and the same black-and-white picture was staring at me in the tiny book. We took a taxi to the airport and Mom bought me a teen magazine to read on the trip. I asked her if Dad was sad and she gave me a pill that she said would soothe my stomach. I asked Father Marcus why he wasn’t wearing his collar, and he said it was easier to get through Customs that way. I don’t remember much else. I was fast asleep before we even boarded.

When we got off the plane, Mom told me we were in Brazil, the land of spices I pointed to on a map. It was so dry and hot that I asked if there was a pool. She said there was an ocean. We arrived in a town called Biguaçu, and a man with a thick-tongued accent took our few bags up a walkway, and we entered a brick house, the side toward the sun a shade lighter than the rest, at the end of a solitary street with a white swing outside. I loved the place as soon as we walked in. It smelled of Father Marcus’s cooking.

It took my dad three days to discover we were gone. Sometimes my mother would leave dishes on the stove for my father to heat up, or he would order takeout if she was busy at church. With the upcoming first confessions, he thought she would be spending most of her time there. He only noticed on the Sunday when he went to Resurrection and didn’t see her or me in the choir. My mom told me this after she talked to him for the first time. He had called the police.

On the fridge was the church bulletin, held up with alphabet magnets like one of my pictures or report cards. He found it on the Sunday and searched it for a mother-daughter retreat or other function he hadn’t heard about. He read the whole thing three times and handed it to the officers as possible places to look for us. They asked him some questions, told him that Father Marcus had also disappeared, and that maybe finding one would help them to find the others. My father offered them some beer and they read the bulletin together. Under “Obituaries and Announcements” was my mother’s short and sweet article: “Rebecca Creely has moved on to greener pastures. She leaves behind her husband and asks him not to worry.” One of the policemen pointed it out. My father hadn’t noticed. She had used her maiden name.

Apparently he continued on fairly normally. Except for the chuckles when he walked by, my father’s routine didn’t change at all. He called me after a couple weeks, or I should say I did, and I told him that we were happy here. He said he was happy. I asked him if he was eating okay. He answered that the church was sending him food for the next while; he was well taken care of and had so many casseroles and cookies he would probably have to throw some to the birds. I told him I loved him. He said he was going to read the paper.

One of the women who baked for my father was a widow. Her husband had died in a car accident or something. They don’t talk about it much. She and my father were married within two years and the chuckles lessened. They were joined together by Father Brown one year before he retired. They replaced the other priest with a Canadian. My father calls and asks me the same questions he did six years ago. I tell him I skip rope and love to sing. I tell him I go to church.

None of us do. We still pray, but don’t go to church. I have a stepbrother from a previous marriage of Father Marcus’s. His name is Brio and he has the room beside me. We are learning how to cook together and go to the same school. I have let him touch my breasts the way we are taught to hold tomatoes under the tap. I know I should stop this, I’m only fifteen, but I don’t know if I can stop myself, and here, I don’t have to go to confession.