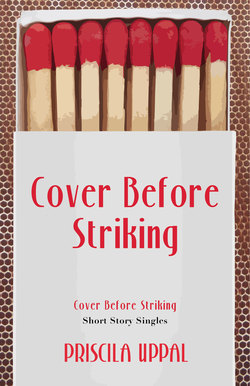

Читать книгу Cover Before Striking - Priscila Uppal - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Cover before Striking

ОглавлениеThe most common phrase in the world in print is Cover Before Striking. Thousands of books with tiny cardboard flaps in every language telling the same story, the same lie. It’s madness to think, with all the warnings, no one seems to be listening.

every language telling the same story

Crazy was a word my father used a lot, especially in association with women. Women were invented to create havoc for men, my father said. Fire-eaters. Looking to cause trouble where there doesn’t need to be any. Set fire to your pants and then to your house. That’s what women do. You would nod and make faces. I would say nothing, until later, in my bed, when he would rub my belly and ask those questions. I would have to answer. Crazy. Irrational, if he felt like being more psychological about it. Those things never happened. You made them up. You’re always telling stories. You are lying.

a word my father used a lot

Lying crazy on your living room floor. Burgundy carpet burned, frayed, pink spots from vodka spills, keeps my back warm, tickling like fur on my knees. Yellow plastic ashtray bought at the discount store in the market, Made in Taiwan. You laughed and said we were all Made in Taiwan. And I imagined myself being melted into a shape with grooves for sticks and fingers to fit. With small black type across my back and ashes smeared on my face. Watch the smoke curl and rise like runaway clouds in a storm, afraid of catching the fever, paper burning in staircase spirals the way I thought fairytale houses would, filter glowing like a pulsating wound, flicking my lighter on and off, on and off, each crack from my fingertips making me tremble. Intoxication. Your feet dangle over my hair, wide and black spread on red. Yellow light telling me to slow down. Slow down. The dizzy feeling in my belly, the downtown traffic. Gazing at the ceiling, dripping the last swig of vodka onto my thighs to mix with your come. My grooves sore but aching for your fingers. I am lost in the smoke.

curl and rise like runaway clouds

He would smile when he said it. Dark thinning hair without a part. Bushy eyebrows furled in amusement. Lips a tense bow. Arms like pendulums. I never knew which side he was going to take. Swing. Swing. I wanted to hit him. Make the movement stop. Take his balding head in my shaking hands and beat it on our yellow fridge, watch the magnets (mushroom, doctor’s number, pizza place, preschool blushing heart), watch them fall to the floor like exploding stars and the picture I had drawn three years earlier, still up on the fridge because no one paid attention, curled at the corners, smudged with fingerprints, grease from cooking, frying our food always in too much oil. Everything we ate in shades of brown or black, burnt bread and fried, trying to disguise the smell with fans whirling, whirling smoke and ashes all over the kitchen, beating the alarm with a broom handle to stop the wailing, wailing, announcing our food was overcooked, overdone, again. Stashing the broom in the crack between the fridge and cupboard. I wanted that lilac to fall. All other flowers wilt. I wanted to press his face up against it, beat him with the broom handle I’d felt on my back, my back, and lower than that. Make him bleed. See I was still a child three years ago drawing with Crayolas, sometimes unable to stay inside the lines.

all other flowers wilt

Dinnertime. I am tired of mashed potatoes and peas, green and white mush served in sterile silence. Only sometimes a smile from the pretty nurse, the one with long raven black hair feathered like crows’ wings, brushed back into a silver pin that glitters under the blinds. I want to feel her hair and have her feed me with her large spoon like a child. I usually accept another helping to watch her move, row by row. I know I could’ve been a nurse like her. I like to think she could’ve been me.

Dinnertime