Читать книгу The Lilies - Priscila Uppal - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

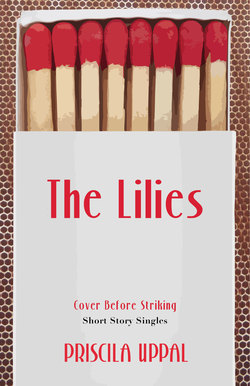

The Lilies

ОглавлениеThe thick cotton gardening gloves she had buried quickly, by the maple tree in the corner of the backyard, near the fence. The dog had shown too much interest in her quick digging, circling around her nervously, threatening to bark, and she had done a clumsy job. She would have to go back out and re-bury. The threat of the neighbours watching weighed upon her chest, or the thought of her husband finding her there, thinking she had gone crazy. He would blame it on menopause. He was not one to squirm at the word. Secretly, she believed, he enjoyed it. The hot flashes and fiery temperament, the need it created in her to be held. She had become a passionate woman again.

It wasn’t the menopause, she knew, that caused the flowers. They were not visions she had created, though like most things in her household, she didn’t understand their actions. Violet had lived amongst flowers before; they were her namesake. How then, she wondered, can they just turn on you? Drinking her rum and Coke, she sat slouched in the kitchen as the dishes stacked in the drying tub. She let the alcohol steep in her body. Maybe some sleep would help. But she was wide awake, and then there was Pickles, who was running around the hole, sniffing the evidence.

Violet worked in a fruit-and-vegetable store part-time ever since her daughter Claire had moved away to Toronto. She had planted fruit and vegetable seeds for years, and her obsession had only grown with time. The way they smelled while roasting or boiling, how carefully you needed to separate the vines from entwining, and the stick of muddy soil between her thick-fingered hands to make them rise, all provoked her to keep growing. She planted every spring and reaped her harvest until the last days of autumn. Even chopping fruits and vegetables seemed a natural extension of her body. Firm rounded fingers eased themselves around knives and cutters, or the draining hole of a juicer. Working at the store helped her pass the time since her home no longer needed her full-time, not without Claire. Without Claire, there was no “little one” to bring up. “Bringing up Claire,” she would gloat, “was my best work.” Though it wasn’t. The work was awkward and frightening in her hands as she watched the pig-tailed girl blossom into breasts and hips and thoughts about the world Violet could barely fathom. Not that Claire was what you could call “a bad seed.” She wasn’t. No angel, either. Inevitably, after a certain age, Violet knew a child no longer radiates innocence, but Violet had never found Claire innocent. Not even as a newborn. She had fallen from her womb, had tasted blood, and come out fighting for air. Her newborn, she feared, already had a bone to pick with a world that wouldn’t contain her. Adult Claire now occupied an untouchable space, an area of tension like the one between her shoulder blades. Even the sound of her name out loud made Violet sense that Claire would eventually disappear from her completely like morning dew.

Sweat had doubly accumulated from the fear of the flowers and the rush of the alcohol, her face flush as if she had been baking all day. She sat envisioning her gloves underneath the ground rising like yeast into a white balloon with swollen fingers and wrists, digging their way back inside her house. Looking around the room, she tried to shake the thoughts off by repeating the names of common objects: dish, spoon, tablecloth, fridge. However, just as common as anything in her kitchen were the lilies outside. She tried not to think of their gramophone faces, the exposed seeds extended like insect antennae, or the sharpness of their leaves. Stay still, she told herself, as if the flowers were monitoring her movements, heads pointed like ears in her direction, afraid she might wake them from their resting. Pour yourself some vodka. But the alcohol made her blood warm, which sent her back to thoughts of blood. The blood bothered her most. The stench curled on the tip of her nose as she imagined a trail of blood from the gloves tunnelling through the backyard, feeding on itself, waiting to be discovered like oil. Or worse, it being autumn, they might be plotting to rise again in the spring. The dog, still sniffing the area with her hunter’s nose, only confirmed her suspicions. She peed and Violet felt convicted.

The next morning she woke early. Stealing out of bed, as she did every weekday morning to make breakfast before Carl went to work, seemed sneaky instead of sweet today. She couldn’t tell him about the violent flowers, and this morning she woke even earlier than usual, needing to confirm somehow by looking out her bedroom window that she hadn’t imagined the whole incident. There they were: white lilies with their bonnets pulled tightly and tied under their chins, covered in dew as if praying.

She put on her runners and walked the length of scattered leaves to the store, grateful for the early opening of Mack’s. She frequented Mack’s at least two to three times a week. The small talk they had developed over the years charmed her. She knew nothing about his life, really; a few details: a wife, two children, one still at home (no idea what will become of him), the other a banker in Toronto. They were proud, decent. But who would know otherwise? Mack knew she liked poppyseed bagels in the mornings, a pack of cigarettes now and then for the evening that she asked for guiltily, like today, and that she had a sweet tooth for strawberry ice cream. He also knew her own daughter was somewhere amongst his family in Toronto.

“It’s about time, isn’t it?” Mack said, dropping the bagels into a brown paper bag in a swift natural motion.

Violet nearly choked on her words of greeting. Although Mack had been smiling when he asked his question, Violet was wary. Maybe someone had seen what happened yesterday in the garden. Maybe they were talking about her behind her back. She didn’t know what time it was and was happy that she asked for cigarettes, had been shoving them into her robe pocket when Mack spoke. But he couldn’t know about the lilies. No way.

“Time?” she asked. For breakfast? For the time of year she smoked more and, well, drank more? For Claire to return for a visit? She waited for his answer, searching past his inviting smile, reading off the brand names of cigarettes in her head.

“Time to freeze up the vegetables for the winter, eh, Violet?”

She handed Mack a ten-dollar bill, slightly embarrassed at not having caught on to his interest in her garden. He was a few years older than she was, but wore it well, his face relaxed into a soft circular jaw, his hair’s lustre retained though it had lost its colour. Violet, however, thought she’d aged badly, liver spots stubbornly spreading across her arms and a good forty pounds over her hips and waist. She supposed Mack led a fairly ordinary life, same as she, but at the same time the money transaction today felt like an admission of secretiveness. In fact, Violet wanted to take the money back after it left her fingers. She wanted it back inside her fist and wanted to run down the street in her terrycloth robe to her kitchen, fake being sick, and lie down on her sofa. I’m going crazy, she thought. I always freeze my vegetables at this time of year. Everybody knows that on our street. What small talk could be more innocent?