Читать книгу Sleepwalking - Priscila Uppal - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

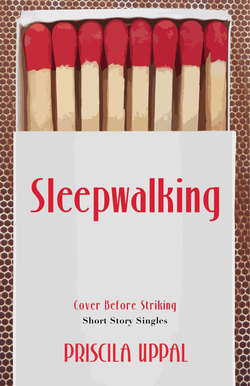

Sleepwalking

ОглавлениеAt first we were as honoured as the other parts of her body: her delicate hands, the square fingers that pushed against objects as if trying to hold them by sheer will; her eyes, blue at birth and then a dull grey, slightly small, almost oriental; her thick hair, even then the shade of oak bark. We were tickled and dusted with talcum powder. We were slipped into fresh cotton socks and tiny white sneakers. People crowded us, comparing the size of their own to ours. Olivia, or as her parents called her, Ollie, was in perfect proportion, until she no longer had anyone to depend on to look out for us. Until she learned how to walk. Then, because she assumed our movements were unconscious, she forgot who was responsible for keeping her up. Ollie the baby was perfect, a sylvan shepherdess; Ollie the adolescent wondered about her hands.

Thin white polyester gloves with sheer frills and tiny yellow flowers. Long purple silk gloves with pointed ends. Pink woollen gloves with bobbles of faux fur. Tiny red buttons, miniature hearts, on cream lace. And a dozen mittens. Ollie’s parents spoiled her hands, let her sleep with gloves on, saying her “Lord’s Prayer” and “Hail Mary” and “If I Die Before I Wake.” She seemed a quiet nun at peace with her vanity. The parents approved, the neighbours approved, and the teachers thought her “precious.” No one condescended to see how we were doing. Not even the doctors who pricked her fingertips (after asking her three time to remove her lovely gloves) seemed to think our blood needed tending. We became grave, and if truth be told, as it must, we became jealous. Weren’t we, after all, the prime movers of her universe? That’s what we thought.

We decided to sleep all day. Ollie tripped, bumped, slid, fell, toppled, teetered, trampled. Ollie could not tap dance or play basketball. Ollie could not climb ladders or jump rope. We were delighted. As an unseen consequence, however, Ollie relied further on her hands. They slammed against floors and cupboards to support her, protect her face. They waltzed around the young boys’ bodies seductively, so that they didn’t care whether she could be dipped or twirled. They moved in front of her, tentatively, instinctively, like the blind. They developed their own language. And we were sore. We wanted to run. We too wanted to feel. We wanted Ollie to watch where she was going.

It came to us as a just revenge. Wriggling and anxious after having slept all day, we needed to stretch. Like a hypnotist we summoned inner strength, staunch desire, made all her matter bend to our will. We slipped off the bed, and, a little frightened by the possibility of her entire body at our command, we simply stood in the dark, pressing our heels into the carpet, unbelieving. We went back to bed, blood racing, causing our limbs to twitch. Then we crashed on our own titillation. That was the first night.

The second night (we waited three days for the second night — how we did this we still don’t know, perhaps afraid we would lose the gift) we became bolder. Found out her hands could be instructed to place a towel underneath her blankets and turn a doorknob. We were on our way outside before her mother, Mommy (still at fifteen), called Ollie. We stopped in our tracks and waited to see if Ollie would wake. She didn’t. We kept on through the kitchen as Mommy ran down the stairs and turned on lights. The mysterious night, which we ached to examine and which had left its corners exposed like unravelled bandages a moment ago, had now sealed itself back up. We were cheated, we thought, until Mommy put a hand on her daughter, and gently directed her upstairs. Apparently, Mommy had previously witnessed this phenomenon. Olivia was regarded as normal. Unconsciousness, like puberty, though disorienting, was a natural state. We stayed and pondered the consequences for a long time.