Читать книгу Vertigo - Priscila Uppal - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

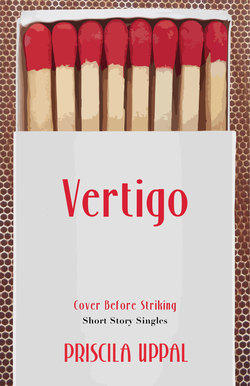

Vertigo

ОглавлениеBottom right corner. Hit. Bottom left corner. Hit. Top right corner. Hit.

My accuracy is over 98 percent, even when the sessions run longer than one hour. I toss up the ball with my left hand, arch my back, bend my right elbow over my head, and serve. Top right corner. Hit. Bottom right corner. Hit.

The researchers love it. Even the poor, tired, neurotic, twitchy graduate students, whose clothes don’t fit, and whose responsibility it is to supervise the monotonous exercise, call out target locations on the tennis grid, and check off each time my serve falls within the lines and within a 2-inch radius a “hit”; even they are visibly excited by my accuracy.

Good job, they say, and nod as I put down one of the research team’s five tennis rackets—it doesn’t seem to matter which I use, although I prefer bright yellow strings as they whip in front of my eyes, I still score the same—let them gather up all the neon green balls and head over to the shower stalls. Good job, like I’ve passed a test. When the truth is, I’m actually failing a test. And I have been for the last nine months.

I’m not a tennis player. I’m a diver. An Olympic-qualifying diver with a difficulty range of 3 to 3.6. An Olympic-qualifying diver who won’t be going to the Olympics. Because I have vertigo.

My father encouraged me to play sports and didn’t seem remotely worried about my bat-swinging, ball-dribbling, bag-hitting, rope-climbing tomboy tendencies. In fact, he frequently took great pleasure in commenting on how fat and lazy the other kids on our street or at my school were. People who sit still aren’t really still at all. They’re digging graves, he’d say, and jump straight into the air tucking both knees, kicking out at the highest point (my mother lost weight without exercising. She could be found at all hours of the day in the kitchen, cooking up a storm, but ate like a bird. I figured she just grazed all day and never developed an appetite for a meal. Meals, for my mother, consisted of spoonfuls from each bowl and tiny cuts of meat; passing the salt and pepper and tubs of sauces; finding the longest yet most elegant way to move a utensil from the table to the plate and then up to her small, bow-like mouth.) then bouncing on his toes once he’d hit the ground.

A man close to 50, but tight and trim, like a coat rack. My father was a runner. Not a professional runner, but a daily runner. There he goes, light as a feather, my mother would say, shaking her head as she peeled carrots or sliced onions or marinated thick rib-eye steaks (I need my protein) for dinner, or organized my schoolbooks in the morning. Always running, running, light as a feather. And she’d shake her head again. The best part of running is the turn home, my father would sometimes say as he glided back inside for a quick reappearance if my mother had sounded more resentful than habitual, if, as my father liked to joke, her Latin roots got the better of her. Athletes appreciate habit and ritual, but not resentment. Resentment is for those who can’t run or dive. And he’d kiss her olive cheek. And then he’d kiss mine. Jump, Dad, jump! I’d scream as a little girl. And he’d jump. And jump higher again. You’re jumping over your grave, Dad! You’re jumping over your grave. And we’d jump up and down, tucking our knees and kicking out at the highest point over and over until mother scolded us. Don’t you two dare talk so casually about death!

But what was death to me then? What is it to me now?

I cared only for sports then. And what was that? A form of order, probably. Something aesthetic. Something you strive for, work for, push your body and mind to the limits for, something so beautiful you are almost destroyed by its presence, but you keep hoping will take you on, as it keeps shifting, changing, betraying, keeping you guessing.

After my shower, I’m expected to report to Dr. Leah Burhauer’s office located on the third floor of the university athletic centre. She is going to weigh me, check my blood pressure, and then ask me a series of questions. Then I’m going to lie down on a blue mat raised on a platform to the level of her waist and she’s going to manipulate my head in several directions. I will stare at her freckled nose while this transpires so she can monitor my eyes and see if they lose focus or twitch. During this procedure, she will ask me the same series of questions again.