Читать книгу SIR JOHN PLUMB - Prof Neil McKendrick - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

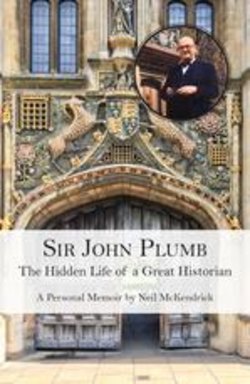

Оглавление3. PREFACE JACK PLUMB: A Personal Memoir from 1949 to 2001

“When we encounter a natural style we are always astonished and delighted, for we expected to see an author and found a man.”

- Pascal

This is an informal and very personal, and necessarily incomplete biographical memoir of Sir John Plumb. Professor Sir David Cannadine has already offered the best critical summing up of his importance to English historiography in History Today and has added further important insights in his formal assessment in The Proceedings of the British Academy. Professor Sir Simon Schema has produced the most affectionate appreciation of his role in keeping alive the traditions of history as literature in The Independent, and Professor Niall Ferguson has written a formal assessment of his work as an introduction to a new edition of Plumb’s The Death of the Past. This offering is an attempt to record some more personal insights about his life and work and character.

I have known Jack Plumb since I was thirteen. I first met him when I sailed as a cabin boy with the Green Wyvern Yacht Club in Easter 1949 – even then he was clearly very different from the other sailors. He was more interesting, more entertaining and much more demanding. He was a Cambridge don, an as yet largely unpublished historian, an exceptional cook, and a frantically competitive sailor who made up for any technical deficiencies in his sailing skills by picking and later buying the fastest boat, choosing the best crew and making sure that they were up early enough to leave before everyone else – arguing persuasively that this would ensure us the choice of the best mooring for the night and the longest period of drinking in the pub. In those days, bitter beer was his chosen tipple (a taste largely abandoned in the late 1960s), cigarettes his drug of choice (a habit given up in the 1950s) and serious wine drinking was still mainly preserved for his more sophisticated friends. The sailing club was a school and university-based society. It sailed as a flotilla of yachts, each of which housed often highly competitive crews of about five or six schoolboys, Old Boys, schoolmasters and an assortment of guests, the most memorable in my time being Pat Moynihan (later U.S. Secretary of Labour Moynihan, Ambassador Moynihan and Senator Moynihan) who effortlessly drank everyone under the table.

Being chosen to crew for Jack was a mixed blessing – his boats were chosen or bought for speed rather than comfort, but everything that money could buy was employed to make the week’s sailing a memorable experience. His fastest boat, Sabrina, was dismissively nick-named “The Gilded Canoe” by those sailing in the larger, heavier, sturdier boats which trailed more sluggishly in its wake; his food was disdained as the product of the “Garlic Galley”; and his fellow sailors were pitied as the galley slaves in Plumb’s forced labour crew. I felt that the cooking and the speed and the conversation more than made up for the shouting and the cursing and the incessant insistence on maintaining our competitive edge. It was a good introduction to Jack’s teaching methods in Cambridge – on board his yacht, as in supervisions in Christ’s, he saw his role as part teacher, part father-figure and part tyrant.

Having known him for over fifty years and having seen him within hours of his death I feel that I have gained some insights into the man.

Having observed the full curve of his adult career, I can claim to know him pretty well.

I came from a very similar background. I lived in the same Leicester street that he did, went to the same grammar school, was even taught by the same two history masters there some quarter of a century after he was. He taught me and directed my studies for three years in Christ’s. He was even – very briefly – my tutor. I shared a staircase with him in the First Court for five years (three as an undergraduate, one and half as a graduate student, and half as a Research Fellow). I can, I feel, fairly be described as both a product of the Plumb school of history and a product of the history school which produced Plumb.

My family and I also shared a house with him in Suffolk for over thirty years. I wrote a book with him. I edited his festschrift, worked on “Plumb’s century” and discussed his work with him on a daily basis during the most productive years of his life. I have been asked to give innumerable speeches in his honour and he, in return, spoke as the best man at my wedding. My family and I took holidays with him for at least thirty-five of the last fifty years of his life and I have dined with him more times than either I can or care to remember. I knew almost all of his friends, many of his male lovers, some of his mistresses and most of his professional rivals.

When I wrote his obituary for The Guardian, I was generously offered 2000 words in which to do so. But since he died on a Sunday and my obituary appeared on the Monday morning little more than twenty-four hours after his death, I obviously did not have the time or the space to say all that I would have wished to say. He was a complicated man, and so I welcome this opportunity to expand my obituary and to expatiate a little more on some of the complexities that made him such a fascinating and maddening friend and colleague. If nothing else it will contain quite a lot of information about his life that few others will know about and even fewer might wish to record. It is very far from all that I could say but the time is not yet ripe for the publication of all the rich details of an exceptionally full life. His archive was purchased by the Cambridge University Library (for the surprising sum of £60,000 several decades ago when that sum would have bought a pretty substantial house) and will provide rich biographical pickings when it is free from its fifty-year embargo. Some sections of it are even embargoed until the death of the last surviving grandchild of the current monarch.

On the Sunday of his death when I was writing his obituary, my younger daughter said, “Forget about the black years and concentrate on the good Jack”. That is what I tried to do. But one cannot deny that the last years of his life were often very black indeed. To try to explain what happened to Jack in his later years I have added “A Postscript on the Black Years”. It was difficult to write and the contrast between the man it portrays and the ebullient, inspiring and uninhibitedly generous man about whom I wrote in a “Valedictory Tribute” when he retired from the Faculty in 1974 is painful to contemplate. Without it, however, this personal memoir would be incomplete and the portrait of Jack would be cosmetically distorted by excessive censorship and excessive kindness – he would have disapproved of the former and despised the latter. In his old age, he rarely practiced either.

I make no apology for this portrait being presented very much from my point of view. Others doubtless have different perspectives on Jack’s life and character. Doubtless some will disagree with my version and my judgements. Doubtless other portraits will appear. All I can say is that this is how I saw him and this is how I remember his distinctive personality. I have enjoyed casting my mind back to the exhilarating early years of our friendship and have found it curiously therapeutic to try to explain and to understand the later darker years.

He always used to divide people into those who enhanced life and those who detracted from it. We should never forget that for most of his life he was without question one of the great life-enhancers – someone who raised the temperature of life just by being there. But there is more of interest to him than that. Perhaps this memoir will offer more evidence and some greater insight into what kind man was the Sir John Plumb who awakened so many people’s interest in history and literature in the late twentieth century.

I hope that this memoir will be read as an affectionate if un-illusion piece. I hope that it will be seen as genuinely admiring and compassionate in tone and content, if not uncritical in spirit and analysis. I have tried to include some of the more revealing and more characteristic episodes in his career and I have concentrated on those aspects of his life of which I had the most direct experience. So, above all, it is how I remember my old teacher and friend. I owe him a great debt of gratitude – indeed, apart from my wife and my daughters, he unquestionably had more influence on my life than any other individual. If history is, in one sense, the record of memory, then perhaps these memories and very personal recollections can be regarded as my modest contribution to the first draft of a history of a fascinating if ultimately much troubled life.

It was clear in 2001 that, with his death, Cambridge had lost one of its most influential historians of the late twentieth century. It had also lost one of its most memorable characters.

He was one of a remarkable group of dynamic and charismatic scholars (including Sir Moses Finley, Sir Geoffrey Elton, Sir Harry Hensley, (Sir) Owen Chadwick, Sir Denis Brogan, Sir Herbert Butterfield, Dom David Knowles, Mania (Sir Michael) Postman, Philip Grierson, Walter Ullmann, Peter Laslett and Denis Mack Smith) who made the Cambridge History Faculty such an exciting place to be in the 1960s and 1970s. When one recalls that Joseph Needham and E.H. Carr were then at the height of their powers in Cambridge, that exciting young scholars, such as John (later Sir John) Elliott, Quentin Skinner, Christopher Andrew and Norman Stone, had already joined the Faculty, and that ambitious youngsters such as Richard Overy, Geoffrey Parker, Roy Porter, Simon (later Sir Simon) Schama, John Brewer, Keith Wrightson, David (later Sir David) Cannadine, Chris (later Sir Christopher) Clark and Chris (later Sir Christopher) Bayly were beginning their research careers here, it is little wonder that one looks back on it now as a Golden Age which has not been equalled since. It was (as Roy Porter once memorably said of the eighteenth century) “a tonic time to be alive”.

Few if any could claim to have played a more central role in that golden era than Dr. J. H. Plumb as he was then known. As a hugely influential teacher, the most popular lecturer and the most prolific writer, and as an unforgettably colourful character, Plumb dominated Christ’s and Cambridge History during much of this period. In the final years of his life it gave him great pleasure that he had outlived almost all of his contemporaries, and he reacted to the death of particularly fierce rivals, such as Lord Todd in Christ’s and Sir Geoffrey Elton in the History Faculty, with undisguised glee.