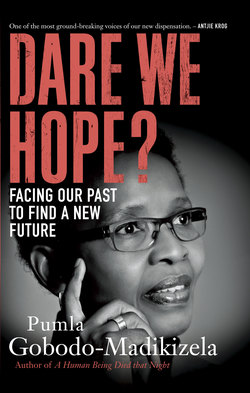

Читать книгу Dare We Hope? - Pumla Gobodo-Madikizela - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

4. The politics of revenge will fail

ОглавлениеThisDay, 19 May 2004

In May 2004, the American broadcaster CBS aired images of the torture and abuse of prisoners in the Abu Ghraib prison at the hands of American military personnel and government officials. At that time, I was on a lecture tour of the United States, speaking about my book on my experiences at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. The events at Abu Ghraib bore an uncanny resemblance to the forms of torture described by victims of apartheid, and I became troubled by the grammar of violence with which the American government responded.

SEVERAL WEEKS AGO I was interviewed on a live show on American National Public Radio (NPR). The occasion was the launch of the paperback edition of my book A Human Being Died That Night,3 and the radio discussion included the third democratic elections since the ANC’s 1994 victory; the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC); how South Africa moved on after the bloody conflict of the past, and some of the challenges it faces now; and forgiveness and reconciliation.

At some point in my conversation with the host, the lines were opened to allow listeners to share their views. One of the callers, an Irish-American woman, questioned the significance of the TRC in the lives of blacks in South Africa. ‘How can they [black people] allow this thing to happen?’ she asked. She went on to express her discontent with current discussions in Northern Ireland about the possibility of introducing a process similar to the TRC.

She made it clear that she was opposed to any idea that would fall short of punishing the British for the years of pain and anguish they had caused in Northern Ireland. She cited ‘Bloody Sunday’, an incident in which Catholic civilians involved in a peaceful march against detention without trial were killed by British troops – an equivalent of the Sharpeville Massacre – as an example of the evils of the British: ‘I want the British to suffer for what they did to us,’ she said. Her anger on air was palpable.

Earlier that day I had lunch with Alex Boraine, former chair of the TRC, in Lower Manhattan, reflecting with a sense of pride on the kind of leadership we have been privileged to have as South Africans, from Nelson Mandela, to Archbishop Tutu, to FW de Klerk and to Thabo Mbeki, and on the achievements of our country: how we got it right, managing to quell the instinct for revenge, even as we continue to struggle with many serious social and economic problems.

At a time when the unfolding story of the 21st century is a pursuit for vengeance through ruthless murder and bloody massacres, violent wars conducted with weapons of mass destruction, peace deals between former enemies collapsing into cycles of bloody conflict, where heads of states are not afraid to publicly declare their desire to target other leaders and to ‘eliminate’ them, one feels proud to be a South African.

South Africa today serves as a reminder of how political leaders can transcend hatred and embody the shared goals of the spirit of national unity. It helps to take a look back and see just how far we have come. The fight for freedom from oppressive laws and for basic human rights, and the government’s severe measures to suppress opposition, ushered in a ferocious struggle between government on the one hand and the liberation movement and the majority of South Africans on the other, which led to a venomous style of engagement that left many dead. The government deemed all who fought for freedom ‘terrorists’ who had to be eliminated.

That is not too long ago, which is why it is remarkable that today the enemies who sought to destroy one another sit on the same side in parliament sharing power as compatriots, and that South Africa is a more tolerant and inclusive society. That South Africa is the miracle that the world sees it to be is largely due to the millions of survivors of apartheid oppression who have chosen not to stoop to the vengeful patterns of history. Some call it reconciliation, others a generosity of spirit and an ability to forgive. But I think it is all these, plus the ‘soft vengeance’ of voting power.

The United States today is a reminder of what South Africa was, and how those in power can breed hatred that produces cycles of violence that go on, and on, and on. When I was in New York, the news was dominated by questions to the Bush administration about the detention without trial of prisoners in Guantánamo Bay, and the infringements of American citizens’ rights in the wake of the ‘war against terror’. Today, America has to face the consequences of choosing the path of making its enemies suffer; America has become that which it loathes. It is a small step from fighting evil to becoming evil.

The wish to inflict suffering means that one has to get into the skin of the perpetrator, become like him, and often exceed the brutality of what is being avenged. American soldiers jubilantly displayed in front of TV cameras the dead bodies of Saddam Hussein’s sons, and we have watched in the news the shocking pictures of decapitated Iraqi children and dead women – casualties of the war, collateral damage they call them. If we accept these excesses in what the Bush administration calls the fight against terrorism, will our intellectual sensibilities allow us to condemn the Iraqis who paraded the charred and mutilated corpses of four Americans in the streets of Fallujah? Can we in all honesty join Senator McCain and other leaders in the US administration in calling the horrific beheading of an American citizen to avenge the torture of Iraqi prisoners in Abu Ghraib ‘barbaric’, without condemning the very act that unleashed this cycle of vengeance?

In the ‘War on Terror’, the tables have turned, and the victim has moved from victor to perpetrator. There is no surprise in the torture by American prison guards at Abu Ghraib. The language of hatred, the lexicon of dehumanisation and torture has been part and parcel of this war. The prison guards felt, rightly, that there could be nothing wrong with abusing Iraqi prisoners, ‘enemies of freedom’, in front of cameras. They have taken the cue from their leaders. President Bush wants the world to believe that the Abu Ghraib images represent actions that are un-American, that the torture is the work of a few bad apples. Well then, it is time to seek alternatives to this destructive war in order to prevent future perverse acts.

America has become our past. We in South Africa are familiar with leaders who encouraged foot soldiers to make the state’s enemies suffer, and then when the moment of reckoning came, told the world that the barbaric acts were aberrant, committed by a few individuals who were inspired not by the noble goals of the government, but by their own potential for evil. This is a good time for the Bush administration to reflect on the escalating bloody violence of this war, and to change course. Revenge – making one’s enemies suffer – is not the right path. Choosing to respond to violence by engaging one’s enemy in dialogue is a risk, but as we know in South Africa, it is one worth taking. That is the lesson South Africa offers the world.