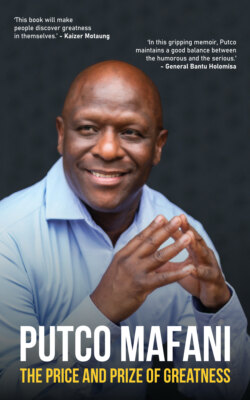

Читать книгу Putco Mafani: The Price and Prize of Greatness - Putco Mafani - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

GRACE TWO

ОглавлениеChildhood adventures and misadventures

My childhood was crazy and wild. One of the places we played was at inqaba – the castle. It had been left there by the British after the wars we fought against them during the nineteenth century. In the early 1800s, the British had an interest in this town and ‘established’ it as their ‘own’. Inqaba was one of the reminders of that war. It was an example of the rich history of the early frontier wars between amaXhosa and the British settlers, and to a lesser extent, the Afrikaners. Iinkanunu – cannons that were used in those wars – are now kept at the local museum. When I got older and understood better the resistance to colonisation, I became proud of the great men and women who came before us for successfully defending Bhofolo from a complete takeover by the colonisers.

A wealth of Xhosa culture and traditions was alive in Bhofolo. For instance, in the practice of ulwaluko – the initiation of boys into manhood. There are reports every year that, sadly, some initiates would not be returning home alive. In almost all the cases, this was caused by the people who managed the process. In Bhofolo, this process was and is monitored closely by elders to ensure that it remains clean and safe. We have never experienced the death of umkhwetha kweyethu indawo – an initiate – at our place.

By the time I went to the bush I could already cook umphokoqo (crumbly mielie meal and samp). Iketse okanye umgqusho oneembotyi (samp or samp and beans); nomphokoqo onamasi okanye umvubo (crumbly mielie meal with amasi) are our staple foods. In fact, by the age of seven I was helping the older boys separate the calves from their mothers when milking the cows. By the time I was eleven, I could tie up a cow and milk it myself. Early each morning, I would do such chores before going to school.

I sometimes feel embarrassed that I did a few mad things in my childhood. Some of these adventures led to unthinkable experiences for a ten-year-old. One of these involved swimming in the nearby river.

Some of the boys I loved swimming with were Boy Bless, Lala Meke, Latsha and Pa; the Mthana boys, Sphithiphithi from Tat’ Gangathela’s house, and Mzuzwana; and big boys like Ncuntswana, Ntwana. My friends, Lhalha, Mzamo, Bhanyamoyi and others, were fanatical swimmers. (This name Bhanyamoyi was his parents’ adaptation of the sound of the Afrikaans words baie mooi – very pretty. His parents must have been hopeful my friend would turn out to be a handsome young man. Well! Bhanyamoyi didn’t live up to that promise. Ha! Yala loo ndaba kuBhanyamoyi! Unfortunately, he did not follow his name! Khohlwa – forget it!)

Although Lala Meke was short in stature, he was a good sportsman, excelling at both rugby and cricket. He was also a brilliant swimmer. Enezigweqe – bowlegs. Wayesuka emakini ke lona – he was a fast sprinter. Latsha and Pa Mthana were brothers and could have been twins the way they complemented each other. Pa was more sociable, whereas Latsha was on the quiet side, yet ever ready to fight. And wayesimela ismoko sakhe! – he stood his ground!

Then there was Sphithiphithi from Tat’ Gangathela’s house and his older brothers Gcuntswana and noNtwana. They had moved into the township from the farms and were not quite township smart. As a result, they were teased a lot about their farm background.

One of our summer activities was to swim in the river. We learnt to swim in the shallow parts, only graduating when the older boys let us. We did not use any artificial things to help us swim. Graduation in swimming expertise was when the other boys told you, ‘Hayi uyayishaya’ – ‘No, you are good, come swim on this side.’ We learnt to swim with the stream and also against the current.

Lala and Bhanyamoyi were amazing swimmers, as they could both dive from the riverbank from a height of something like three or four metres into the water. They could hold their breath under water longer than a minute. Babengenantanga – no one could match them. Bhanyamoyi could also somersault when diving into the water.

We were the premier league of river swimmers, using freestyle against the current.

Sadly, Klefi drowned in the river during one of our stream-swimming competitions. We underestimated the strength of the river after the heavy rains. He got into trouble and we quickly realised the current was too strong for us. We couldn’t save him. I rushed off to get help from the adults, but it arrived too late.

This was a scary experience, and for some time afterwards most of the boys stayed away from the river. I’ll never forget the police recovering Klefi’s body. It was the first time I’d seen a dead person. And not just anyone, but my friend – someone I had laughed with a few moments before.

Our parents admonished us and tried to discourage us from swimming in the river, more so after a heavy rainfall when the river would be full. It was only the next summer that we returned to our carefree ways.

* * *

One charming and intelligent man I grew up with and later connected with is Jongisizwe ‘JB’ Mali. JB was a cunning fellow, brave and extroverted in an amazing way. His family was close to ours. JB Mali, on getting advice from me when he was an initiate, says:

Putco began to make an ever-lasting impression on me as a boy when he and his brother Mlungiseleli Mafani went to the mountain, to commence their journey to manhood. Hlanga, their younger brother, and I would periodically visit them and I would be struck by this very bubbly and funny mkhwetha – initiate – who always out-talked his introverted and stuttering brother, Mlungiseleli. On the December of our own turn to go to the bush, in 1986, myself and Hlanga would periodically get visits from Putco, who would readily dish out all sorts of unsolicited advice on how to carry ourselves as initiates. At times I found him overwhelming to say the least. He would never know when to stop talking, advising and at the same time teasing us about our respective pain thresholds! I hold those teachings to this very day.

Putco’s padkos

I now realise that although I was late to save Klefi’s life, running back to the township to seek help for him was preparing me for deeper painful situations that I would have to deal with much later in life, such as the dreadful Ellis Park Stadium disaster. Sometimes life tests us early to see how we will handle the tough moments when they happen in the future.