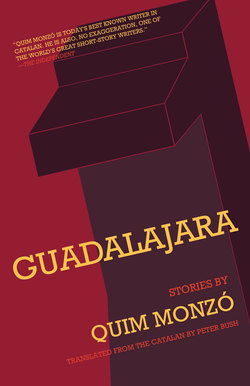

Читать книгу Guadalajara - Quim Monzo - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Gregor

ОглавлениеWhen the beetle emerged from his larval state one morning, he found he had been transformed into a fat boy. He was lying on his back, which was surprisingly soft and vulnerable, and if he raised his head slightly, he could see his pale, swollen belly. His extremities had been drastically reduced in number, and the few he could feel (he counted four eventually) were painfully tender and fleshy and so thick and heavy he couldn’t possibly move them around.

What had happened? The room seemed really tiny and the smell much less mildewy than before. There were hooks on the wall to hang a broom and mop on. In one corner, two buckets. Along another wall, a shelf with sacks, boxes, pots, a vacuum cleaner, and, propped against that, the ironing board. How small all those things seemed now—he’d hardly been able to take them in at a glance before. He moved his head. He tried twisting to the right, but his gigantic body weighed too much and he couldn’t. He tried a second time, and a third. In the end he was so exhausted that he was forced to rest.

He opened his eyes again in dismay. What about his family? He twisted his head to the left and saw them, an unimaginable distance away, motionless, observing him, in horror and in fear. He was sorry they felt frightened: if at all possible, he would have apologized for the distress he was causing. Every fresh attempt he made to budge and move towards them was more grotesque. He found it particularly difficult to drag himself along on his back. His instinct told him that if he twisted on to his front he might find it easier to move; although with only four (very stiff) extremities, he didn’t see how he could possibly travel very far. Fortunately, he couldn’t hear any noise and that suggested no humans were about. The room had one window and one door. He heard raindrops splashing on the zinc window sill. He hesitated, unsure whether to head towards the door or the window before finally deciding on the window—from there he could see exactly where he was, although he didn’t know what good that would do him. He tried to twist around with all his might. He had some strength, but it was evident he didn’t know how to channel it, and each movement he made was uncoordinated, aimless, and unrelated to any other. When he’d learned to use his extremities, things would improve considerably, and he would be able to leave with his family in tow. He suddenly realized that he was thinking, and that flash of insight made him wonder if he’d ever thought in his previous incarnation. He was inclined to think he had, but very feebly compared to his present potential.

After numerous attempts he finally managed to hoist his right arm on top of his torso; he thus shifted his weight to the left, making one last effort, twisted his body around, and fell heavily, face down. His family warily beat a retreat; they halted a good long way away, in case he made another sudden movement and squashed them. He felt sorry for them, put his left cheek to the ground, and stayed still. His family moved within millimeters of his eyes. He saw their antennae waving, their jaws set in a rictus of dismay. He was afraid he might lose them. What if they rejected him? As if she’d read his thoughts, his mother caressed his eyelashes with her antennae. Obviously, he thought, she must think I’m the one most like her. He felt very emotional (a tear rolled down his cheek and formed a puddle round the legs of his sister), and, wanting to respond to her caress, he tried to move his right arm, which he lifted but was unable to control; it crashed down, scattering his family, who sought refuge behind a container of liquid softener. His father moved and gingerly stuck his head out. Of course they understood he didn’t want to hurt them, that all those dangerous movements he was making were simply the consequence of his lack of expertise in controlling his monstrous body. He confirmed the latter when they approached him again. How small they seemed! Small and (though he was reluctant to accept this) remote, as if their lives were about to fork down irrevocably different paths. He’d have liked to tell them not to leave him, not to go until he could go with them, but he didn’t know how. He’d have liked to be able to stroke their antennae without destroying them, but as he’d seen, his clumsy movements brought real danger. He began the journey to the window on his front. Using his extremities, he gradually pulled himself across the room (his family remained vigilant) until he reached the window. But the window was very high up, and he didn’t see how he could climb that far. He longed for his previous body, so small, nimble, hard, and full of legs; it would have allowed him to move easily and quickly, and another tear rolled down, now prompted by his sense of powerlessness.