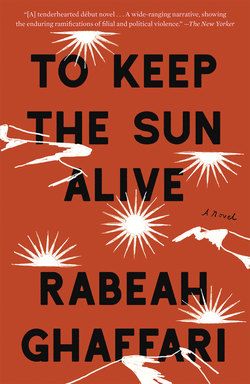

Читать книгу To Keep the Sun Alive - Rabeah Ghaffari - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеSIESTA

After lunch, Mirza unfurled a massive gelim on the deck where the family had just finished lunch. Unlike the house rugs, the gelim did not have a pile weave or intricate designs, but rather bold and blocky tribal patterns. He laid down a pillow and folded sheet for each siesta taker. Inside, the men were changing into shalvar kordi. Even though Shazdehpoor relished the comfort of the pantaloons, their casualness unnerved him. Mohammad slipped into his with an air of relief, and Madjid poked fun at Jafar for pulling his up to his chest.

The mullah’s preparation for siesta was far more formal. He disrobed in a separate room in order to maintain the privacy and sense of decorum appropriate to his status. First, he took off his aba, which he carefully folded and set down on the carpet. Then he took off his ghaba, which he also folded. He then took off his turban and set it down on his clothes, leaving the skullcap on top of his head. He made his way to the platform in his pantaloons and white knee-length shift like those martyrs wear.

The judge always disappeared during siesta. No one knew where he went except Bibi-Khanoom. As soon as lunch ended, he washed up and took a long solitary walk on the dirt road that led to the sand dunes. He found a rock to rest on, closed his eyes, and stared at the sun. It was, in its own way, a kind of sleep.

The family gathered on the platform, waiting for the siesta to begin. Mohammad took his place on the edge of the gelim so that he could turn his head away from everyone, especially his wife. He had lived a measured life, meted out in one small increment at a time by another human being. To everyone around him, it seemed like a life of serfdom, a life in captivity under a domineering woman who controlled every moment of his existence, save his sleep. But he had only ever known such a life. Before Ghamar, he had lived with a mother who ran her household like a military prison—every day scheduled, duties allocated according to age and gender of each child, deviances dealt with harshly and quickly. For him, life with Ghamar was a continuation of the familiar, and gave him a sense of permanence that all beings crave, sometimes at the cost of their own happiness.

His fantasy life was an entirely different matter. Siesta time allowed him to lay his head on a pillow and slip away into his dreams, all of which were about one woman. A woman he had seen once as a young boy, the day his mother had taken him to the public hammam. He sat there, next to his mother, and watched this woman wash her hair. Wrapped in a linen cloth, she knelt next to the pool and poured bowlfuls of water over her head. She gently squeezed the excess water out, then threw her head back and looked up at the skylight. He saw her face at last—and the light and the warmth that emanated from it.

Over the years, he had built an imaginary life with this woman. He courted her, married her, and she bore him children. They quarreled and laughed together, made love and broke bread. He knew the contours of every inch of her face and body. She aged with him, always becoming more beautiful. He set up a home and she decorated all the rooms with fine silk-woven carpets and heavily embroidered floor pillows strewn about for guests. He had given himself a noble profession like that of a judge or a doctor, and this gave him a proper place in society. He was able to provide her with the most exquisite clothes for which she kept her figure trim. Their children were always clean and well behaved, and his wife doted on him and fulfilled his every wish. When Mohammad put his head on a pillow, a smile crossed his face and a calm swept over him, for he was about to see his beautiful, gentle, warmhearted wife.

Mohammad’s real wife spent the first few minutes of siesta staking her claim to space on the gelim. For Ghamar, napping was a full-contact sport. Once situated, she focused on falling asleep as quickly as possible by repeating observational phrases in her head, such as “that cheese was delicious” or “Jafar is a strange boy” or “Madjid is getting browner.” If there was one thing that she feared, it was to be alone in self-reflection.

Nasreen lay next to her mother, unbothered by her constant kicking and pushing. She closed her eyes and focused on the very particular scent of Madjid’s skin. It was elemental and organic like the smell of hard rain on dry rocks.

A safe, modest distance away was Shazdehpoor. He lay on his back staring up at the sky. For him, napping was yet another third-world humiliation he had to suffer. He went over future purchases he planned to make from the English gentlemen’s catalog. He had his eye on an amber glass ashtray, even though he didn’t smoke. And next to him was Madjid, who forced Jafar to lie down next to the mullah. It was always the same. Jafar would stare at Madjid with rounded maudlin eyes, worried already about the mullah’s propensity to release gas as he slept, gas potent enough to choke the life out of the hardiest of men, let alone a small boy.

The mullah’s gastrointestinal issue was a result of dairy intolerance, which would not have been an issue if he practiced moderation. And yet at every lunch he devoured an entire bowl of yogurt with sautéed spinach, browned onion, and turmeric. Poor Jafar was laid to waste in the aftermath.

Madjid looked at the dejected boy and whispered, “Just remember that someday you’ll be able to fart on someone else.”

The food induced sleep in everyone immediately, except for Madjid and Nasreen. They slipped out of the pile of bodies and tiptoed their way into the thick cherry trees. The whole affair felt exhilarating and dangerous; each time they met seemed wildly urgent.

It had been almost a year since their relations had become sexual. Their first innocent kiss that took them from friendship into courtship, followed by an afternoon where they devoured each other’s neck, Nasreen later concealing Madjid’s love marks with a chiffon scarf. Next, Madjid had explored her bosom. After that, it was not long before they were naked and entwined, fumbling their way through an act that was at once innate and acquired, at times even comical and inept.

And now, finally liberating.

After their tryst today, Madjid burrowed his head between Nasreen’s breasts. Then fell asleep, while she stroked his hair and looked up at the black cherry tree, its branches hidden by a thicket of oval leaves enveloping clusters of dark fruit. The wind let shards of warm sunlight intermittently cut through.

The sun was at its highest point and its strength washed over the sky. Crickets, wasps, and bees sang all around them, with a constant “zhhhh” that vacillated between a soft tone and a deafening, monastic drone. With eyes half-closed, Nasreen let herself fall into its trance, always aware that she could not let herself fall asleep.

She woke him with a gentle kiss to his forehead. He rolled onto his back and stared up at the canopy of trees with her. She squeezed his hand and turned to him. “Let’s get out of here.”

“Already? We have more time.”

“No. I mean out of this place. Let’s go to the capital. Anywhere but here.”

He turned to look at her. Their faces almost touched. He saw the desperation in her eyes. “Nasreen, if your mother can get to you here, she can get to you everywhere.”

Nasreen sat up and started buttoning her dress. “So that’s it? We’re just going to stay here and wither away like our parents?” She caught herself and turned to him. “I’m sorry. I didn’t mean your mother—”

“It’s all right. But if we leave, it should be for something better. Not just to get away from something unbearable.”

“My mother is relentless. Every day it gets worse. The only time that I have any peace is when I’m in my room or with you. I want to go to the capital and try out for the theater troupe. Maybe work at the box office and work my way onto the stage. Take classes. Get an apartment. Meet up with friends at the coffeehouse. Talk about things that matter to me. Laugh as loudly as I want. Lie in a real bed with you—”

He was sitting up now, no longer listening to the litany of her desires, but watching the tears pour down her face.

“I don’t have a life, Madjid. And I want one. With you.”

He pulled her up, cupping her face in his hands as he spoke. “I know what you are up against. I see how hard it is on you. But you are more alive than anyone I know, and if we have to go somewhere else just so that you can see what I already see in you, then I promise you, we will do it.”

Nasreen brushed away her tears and smiled.

They began their walk back toward the house side by side. Right as they were about to step out from the row of trees, he turned to face her. They stood there in silence looking at each other. He kissed her on the forehead, and watched her walk back to the siesta, then made his way to Mirza.

Mirza lived in a small shack in the orchard that he had built himself near the entrance. It was one room with one door and one window. The décor was Spartan. The most prominent item was a carpet given to him by Bibi-Khanoom as a housewarming present. He took his meals on that carpet and he slept on it as well.

As Madjid reached the shack, he saw the door was open. Mirza was busy in the corner fiddling with the spigot of an oak barrel. He whipped around with a cup in his hand as he heard Madjid approach. “Some medicinal juice?”

Madjid let out a hardy laugh. “Of course.”

He took the cup and sat on the carpet as Mirza filled his own and took his place beside him. Mirza studied Madjid’s face. The flushed skin and tousled hair of a young man in love and full of lust gave him pleasure. He lifted his cup to Madjid and toasted him as he always did, with a quatrain from Omar Khayyam’s Ru’baiyat. “Come, fill the Cup, and in the fire of Spring your Winter-garment of Repentance fling: the Bird of Time has but a little way to flutter—and the Bird is on the Wing.”

They both threw back the wine and rolled their tongues around their mouths, tasting resin residue. Mirza bounced to his feet to refill their cups with an almost childlike enthusiasm. He tilted and shook the barrel to get the wine to flow. “It’s getting to the bottom. Time for a new batch at Chateau Mirza.”

Madjid remembered the first time Mirza had invited him to his room. He had sat on the carpet and, as he looked about, he had realized that other than the carpet and the oak barrel, the only things there were a wooden backgammon board, a small pile of clothes, and some toiletries. Not one book or photograph. Not one trace of a past life. “Who are you?” he had asked.

“I am no one,” said Mirza. “More juice?”

Today, Mirza spoke of mulching plants and pruning trees. He spoke of the turning of leaves and the migrations of the birds and insects. He spoke of the movement of the sun and the motion of the wind in spring, summer, autumn, and winter. He spoke of the moodiness of the hens and the stubborn old goat that would latch on to his pant leg during the morning feeding. An animated glee had swept over him as he went on about these things, and Madjid realized that Mirza had become the orchard itself. And he wondered how unbearable some lives must be that they have to be abandoned to go on living.

Mirza brought out the backgammon board. It was made of heavy walnut wood with intricate geometrical engravings. “Black or white?” he said.

“Black.”

They each took their checkers and set up at a rapid pace. Mirza tossed one of the rounded ivory dice to Madjid. “Less or more?”

“Less.”

They simultaneously threw them. Madjid’s landed on six while Mirza’s continued to spin. It landed finally on three and Mirza immediately grabbed the dice and started the game. They played fast, tearing through two games in under five minutes, with Mirza winning both. On the third game he was so far ahead of Madjid that it was likely he would beat him before Madjid was able to get all his pieces home. Mirza shook the dice in his hand, mocking the young man. “I smell the stench of marse.”

A double loss. But Madjid was not ready to admit defeat. Not yet.

Mirza blew on the dice and threw them. They both watched the dice spin and slow to a halt, landing on a double six.

“My God,” said Madjid. “What luck you have!”

Mirza looked up at him and smiled a smile that barely masked a sadness he would never explain. “My luck begins and ends with dice.”

Bibi-Khanoom stood at her kitchen counter with her ghelyan and a tobacco box. She refilled the base with fresh water and packed the bowl with tobacco and covered it with a screen. She placed a small square of coal on the screen and lit the coal. She gently blew on the coal and carried the ghelyan back to her bedroom to wait for the arrival of the midwife.

The midwife was Bibi-Khanoom’s oldest, dearest friend. She lived in a one-room shack just a few minutes’ walk from the orchard, on the outskirts of town. It was surrounded by sand dunes, desolate and barren.

The midwife had delivered Naishapur’s newborns for more than fifty years, but had been forced into retirement after a difficult birth that almost killed the child and mother. Though it was through no fault of her own, the townspeople no longer trusted her.

The midwife rarely came to the Friday lunches. She preferred spending time with Bibi-Khanoom alone during the siesta that followed. She would always show up to return the plate that Jafar had delivered, and they spent the afternoon together in Bibi-Khanoom’s room, smoking. Each would recline on a floor pillow, holding her own amjid, an ornate mouthpiece they put on the hose as they passed it back and forth. Sometimes they would play a few rounds of backgammon or a card game such as hokm or pasur. Other times they would sit silently inhaling and enjoy the lightheadedness of the nicotine, speaking in turn in a call-and-response. The midwife always went first. Lately, her subjects were morose. “I am afraid of death,” she said.

“How can you be afraid of what you do not know?”

“It is exactly why I am afraid.”

The midwife had spent her whole life in the service of creation, losing count of how many births she had facilitated. And yet the mystery and wonder of the act had never ceased to move her. That very moment when she would yank a blood-covered infant from the birth canal, holding it up and slapping a first cry from the child—a sound so primal, so primordial that she believed it was the voice of God, if ever there was such a thing.

But death was silent and this frightened her. “There is no wisdom that comes with age, Bibi-jan, only acceptance.”

“But that is wisdom, my dear.”

“Each night I go to bed fearing I won’t wake up. I am waiting to die.”

“We all are, my dear. It is just that those of us closer to it are waiting with greater anticipation.”

“I am tired of waiting with anticipation.”

“Some tea will make you feel better.”

“Yes, that would be nice.”

Bibi-Khanoom looked out her window now and saw the midwife coming down the path toward the house. She was a whisper of an old woman, gangly, hunched, and bowlegged, but she moved with the spirit of a young girl. When she reached the house she went straight to the kitchen and set down her plate, then headed to Bibi-Khanoom’s room and gently knocked on the door.

“Come in.”

She took her place on the pillow and let out a sigh. “Thank you for sending Jafar. You didn’t have to do that. You are too kind to me.”

“It was my pleasure. Besides, that boy can use some exercise.”

They looked at each other and laughed, each of them cupping her chador over her mouth. As soon as the laughter subsided, they let go. Bibi-Khanoom shook her head as she took her amjid off the hose and handed it to the midwife. “I worry for him so.”

“It’s just baby fat. He’ll grow out of it.”

“No, not for that.”

“He still hasn’t spoken?”

“Not a word.”

“And at school?”

“Just reading and writing.”

“And what does your husband have to say about it?”

“He said, ‘Let the boy be. He’ll come to things in his own way. Everybody talks but how many people can listen?’ I should never have let him tell Jafar he was adopted. I think it frightened him. He insisted that the truth would make Jafar strong, but I think it made him sad.”

“The only truth that matters is that he is your son and you have raised him.”

The midwife slid her amjid out of her bra and put it on the hose. She kept everything she owned pinned to her bra. Whenever someone needed something, she would reach in and pull it out: tissues, pins, stockings, lip stain, and even a small container of rubbing alcohol. She also kept her jewelry in there. And if anyone looked at her strangely, as she dug around, trying to find something, she would say “keep what you need close to your heart and let the rest fall away.”

The midwife had delivered Jafar. She was the only one who knew the identity of Jafar’s mother and he was the only child that she had ever delivered who had been born in the caul. The moment she split open that amniotic sac, she knew she was exposing him to a world of fiction, because she would never tell a soul that his birth mother was a prostitute who lived in a shack across the road.

Jafar’s mother had refused to look at the child and put her hands over her ears so that she would not hear him and finally screamed to have him taken away. The midwife pumped the mother’s breasts and fed the boy herself. His mother lay in bed, despondent and stoic like a factory cow. Even after the midwife had taken the boy to Bibi-Khanoom’s, she returned to the mother to collect the milk and bring it to the orchard, only once speaking of the boy—to falsely declare that a family had been secured for him in Mash’had.

The midwife pulled deeply on the ghelyan and let out a gust of smoke.

“The pickled eggplants were delicious,” she said.

“I made them for you.”

“They are my favorite.”

“And the tahdig? I think it turned out perfectly this time.”

“What tahdig?”

Bibi-Khanoom stood up, muttering to herself, “That boy!” She pushed the window ajar and whisper-yelled, “Jafar.” Half asleep on the platform, he opened his eyes in terror. He knew why his mother was calling him and he began to hiccup-sob, just as the mullah let rip another clarion call of gas.