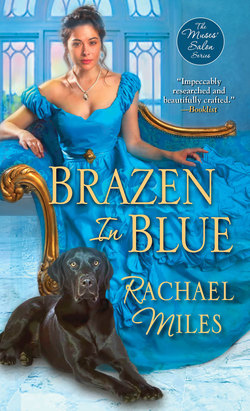

Читать книгу Brazen in Blue - Rachael Miles - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter Two

Four months later

“He’s a handsome man, your betrothed,” Mrs. Burns announced for the thirtieth time, her voice a yellow-green linen. Sweet, but dim, the parson’s wife had been monitoring the carriage yard for the last hour. “And so generous. Look there: to every child, Lord Colin gives a bit of hard candy.”

Lady Emmeline, the bride, forced herself to sit patiently as Maggie, her maid, threaded a long string of pearls through her dark hair.

When Emmeline had accepted Mrs. Burns’s offer of help, she’d expected something more than a running catalogue of carriages, guests, and clothing. But Mrs. Burns’s patter helped distract Emmeline from the tight ball of anxiety in her belly, and for that Emmeline was grateful.

“Look at that carriage painted in gold, red, and green fleurs de lis,” Mrs. Burns exclaimed. “I’d fear for the highwaymen if I rode in that. Who would have such a thing?”

“That would be my cousin, Mrs. Cane.” Emmeline took care to sound neutral. New to the parish, Mrs. Burns and her husband had not yet been in town for one of Stella’s visits.

Mrs. Burns continued unfazed. “She’s stepping out of the carriage now. That dress must have twenty pounds of lace! You’d think she was meeting the queen.”

“She wishes to impress my fiancé’s brother, the Duke of Forster. They’ve never met.” Emmeline nodded to Maggie, who was holding out a spangled veil to cover Em’s hair and shoulders. “Remember to leave my face uncovered.”

“I know: you ‘are not a prize to be revealed at the altar.’” Maggie mimicked Em’s voice.

And I will not hide my scars. Em left the words unsaid. The word broken rose up in her memory, but she refused it.

“I remember your mother wearing this dress.” Maggie stepped back and studied her work, clearly pleased. “She’d be proud to see you wearing it all restyled and modern.”

Em felt tears well up, but blinked them away. Nodding to Maggie that she was no longer needed, Em rose carefully and stepped to the pier glass. She breathed in deeply and looked.

She focused first on her mother’s dress, a watered-silk round dress with a bodice lightly patterned in delicate embossed stripes. Its neckline curved from puff sleeve to puff sleeve, revealing gently mounded breasts. Delicate lace circled the base of each sleeve and the top of each long kid glove. The same narrow lace trimmed her décolletage and ran down the sides of her bosom. Though the top of the skirt fell in clean lines, the bottom blossomed into flounces of broad lace topped by silk bouquets of blush roses and orange blossoms. The mirror-Emmeline looked like a confection or a princess out of a child’s fairy tale.

Emmeline pulled back the spangled lace framing her dark hair and studied the scars that ran down her cheek and jaw. When she was a child, the thick red welts had drawn Stella’s ridicule. To avoid seeing them, she had learned to look in mirrors selectively—to examine a hat, a bodice, a shawl—but rarely to look herself fully in the face. But today, of all days, she needed to see herself whole.

In the mirror, beside Colin’s confection-princess, a new walking stick rested on the ottoman. A wedding gift from her fiancé, Lord Colin Somerville. Crafted of fine rosewood, the stick hid a core of sharp tempered steel. Emmeline might need the walking stick to support her when her leg failed or to protect her as she traveled her lands. But the lace-flounced woman in the mirror would carry a walking stick purely as an adornment.

Emmeline sighed. In everyday life, she wasn’t the sort of woman who dressed with such elegance or who wore so much lace. Or was she? Emmeline’s wardrobe for their wedding trip had been designed by London’s most-sought after modiste, Madame Elise. Colin, knowing Emmeline’s aversion to London, had brought Madame Elise from the city to Em’s estate. And now, in the estate office, a dozen trunks were packed tight with morning dresses, walking dresses, evening dresses, hats, gloves, petticoats, and chemises, all from the most recent fashion plates. Another of Colin’s gifts for their wedding trip.

But, wardrobe or not, Em had little desire to travel. She’d told Colin as much. She’d prefer to remain at home, watching the seasons turn from winter to spring and back again. Monitoring the cold earth’s temperature until it grew warm enough to nurture spring crops. Watching the trees’ bare branches transform from slight green bud to unfurled leaves. Listening to the songs of the migrating birds announcing their return to the forest and river. Other young ladies of rank had “seasons” in London: Em reveled in the seasons of her land.

But Colin needed to escape from England. He never said it, but she could see it in the way his eyes hooded with sorrow and regret when he thought she wasn’t looking. They were both haunted by memories and loss. Hers were old wounds, best left untouched. Colin’s wounds were fresh—and all her fault. “You won’t deny me the pleasure of meeting my father-in-law,” he’d said as he kissed her forehead. “We’ll be home for the first harvests, I promise.” She couldn’t refuse him: to the Continent they would go.

Even so, she felt unsettled. She studied her confection-princess-self in the mirror. She felt like the frog-prince in the Grimm brothers’ story, cursed to appear as a frog until the kiss of a princess transformed him back into his true shape. But in Emmeline’s case, the story was working in reverse. She might be a lady by rank, but her life, to this point at least, had been with the soil, her land, her people. She liked nothing better than to put on a working dress and walk her fields. A happy frog in her native mud.

But being Colin’s wife, wearing the clothes he’d bought her, traveling to her father as if she were a dutiful daughter—all those things turned her from a humble estate-frog into a lace-princess. Eventually, at least, she and Colin would return home, to her land, to her crops, and she would put on her old frog-clothes and return to work. Surely it would be that easy. Or would her old self, the one unafraid to dirty her hands in estate work, be lost to her? She held out her hands, imagining field dirt under her nails. Without thinking, frog-Emmeline touched her princess-self in the mirror, but she felt only cold glass, not another’s flesh. Could she be both the princess and the frog?

“Ah, look there.” Mrs. Burns, still staring out the window, broke into a titter, breaking Emmeline’s reverie. “Your cousin’s met the duke now. And that curtsy! I didn’t know a woman could curtsy that low and still stand up.” The parson’s wife paused. “Oh, dear me, I guess one can’t. She appears to be stuck.”

Emmeline left her troubled thoughts in the mirror to join Mrs. Burns at the window. Sure enough, her cousin Stella stood balanced mid-curtsy.

“That’s odd.” Mrs. Burns giggled. “Before she curtsied, her husband and a tall lad were right by her side. Where have they gone?”

Emmeline watched as Colin and the duke helped Stella to stand.

“She must be embarrassed, poor dear. She’s batting that fan fast enough to cool Hell.”

Emmeline said nothing. More likely, Stella had rehearsed that failed curtsy for hours, to gain more of the duke’s attention. The duke should likely check his pockets to see if they’d been picked.

“Ah, look, she’s fainted a bit onto the duke’s arm, and he’s having to escort her into the chapel.”

Emmeline smiled in spite of herself. She had no question that Aidan Somerville, the Duke of Forster, could manage Stella and her stratagems.

A sharp tap at the door preceded the entrance of Mr. Jeffreys, Lady Emmeline’s majordomo. With Maggie’s exit, he had come to retrieve Mrs. Burns.

“Isn’t Lady Emmeline such a lovely bride, Mr. Jeffreys? And this dress! Right out of last month’s La Belle Assemblée, isn’t it?” Mrs. Burns placed her arms akimbo and studied Emmeline. “Your Lord Colin is a very lucky man, my dear.”

“I believe Lady Emmeline would appreciate some time for . . . quiet reflection and prayer.” Jeffreys as always chose his words with care.

“Of course, of course.” Mrs. Burns kissed the air next to Emmeline’s cheek. “Don’t you worry, my dear: I will join you at the back of the church. Mr. Burns has a lovely homily planned. He’s borrowed a bit of fire and brimstone from the Calvinists, but transformed it to the fire of human passion, or something like that. I’m never quite sure. He’s such a clever man, my Mr. Burns.”

Then she was gone.

The room turned quiet. Without Mrs. Burns’s chatter, Emmeline’s anxiety reasserted itself in full force, the tension in her chest making it hard to breathe.

From the window, she could see that the duke once more stood by his brother’s side. By his presence and his smiles, the duke demonstrated to all that he approved of Colin’s match.

Her match.

She forced herself to breathe in slowly. They were always meant to marry, she reminded herself. Colin had declared that intention years ago, and no one—except her—had found it remarkable when he’d finally asked for her hand. She’d done nothing wrong in accepting. It was a fine match, and he would be a fine husband.

She studied Colin from the window. To her cottagers, he offered hearty handshakes. To the village spinsters, he gave a gracious half bow that left them blushing and tittering. To everyone, he was charming and kind. But of course he was.

When had she known him to be anything else?

She loved him. Of course she did. She always had. Their life together would be happy, pleasant, cheerful, useful. He would let her run her estate—she would let him do his secret work for the Crown. Why then did she feel her life might be ending rather than beginning?

* * *

She joined her dog, Queen Bess, at the warm hearth. Bess, sensitive to her mistress’s emotions, raised her eyebrows, and Emmeline leaned down to scratch the dog’s head. “There, girl. It’s all right. I’m merely anxious. Nothing to be worried over.”

The dog leaned her head into Emmeline’s hand, and Emmeline blinked back tears.

“You love him too, girl, don’t you?” Emmeline rubbed Bess’s ears, until the dog’s tail wagged. Emmeline stood for several moments, letting the fire warm her. But the chill she felt deep in her chest couldn’t be lifted. “If we were to run, girl, where would we go? Can you see us, both with bad legs, limping across the field?”

With a sad laugh, she turned back to the window. But she moved wrong, and the old pain shot angry through her leg. She gasped, and Bess pulled herself to her feet, instinctively positioning herself between Em and any furniture. Em rested her hand gently on the dog’s broad back, grateful for the extra support. When the pain subsided, she moved more slowly, careful to step just right. Bess followed at her side.

She’d stepped wrong with Colin when she’d agreed to marry him. Had he asked her privately, she could have tested his heart and hers. But he’d chosen Stella’s house party, with Stella and all her friends watching. Even at the moment she’d said yes, her heart had cried out no. Afterwards, she’d found herself carried away by Colin’s assurances. “It was always supposed to be you and me, Emmie,” he’d tell her as they planned the wedding dinner or looked at maps to plan their wedding trip. But in all the months of their engagement, Emmeline hadn’t had a peaceful night’s sleep.

Marry or run? Whatever decision she was going to make, she had to make it.

She surveyed the carriage yard where Colin and the duke greeted their guests. Sam Barnwell, her estate manager, had joined them, introducing those few Colin didn’t know. During her wedding trip, Sam would care for her estate. She had no worries there: he had been her steward for years.

Behind Sam stood Colin’s family, his brothers—Lords Seth, Clive, and Edmund—and their elder sister, Lady Judith. Her family. They had welcomed her into their hearts from the moment Colin—still a boy—had announced his intention to marry her. They had visited and written faithfully. Herself little better than an orphan, she’d drunk in their affection. They had been her confidantes, her friends, and she couldn’t imagine a life without them. Her hand clenched.

Seeing Colin’s family should calm her, not make her ill at ease. She had nothing to fear, but even so her chest constricted, and her sense of near panic swelled. She picked up her walking stick, so much more necessary in the last weeks, repeating, “All shall be well. All shall be well. All manner of things shall be well.” But the familiar litany offered her no peace.

At that moment, a carriage she didn’t recognize pulled into the yard. Colin’s friend, Lord Walgrave, stepped out, then handed down a dark-haired woman.

Lucy.

Even from a distance, Lady Fairbourne appeared frail and too thin. Emmeline’s guilt welled up, thickening her throat.

Emmeline watched for Colin to notice Lucy’s arrival. She needed to see his reaction. But he was deep in conversation with a local magistrate.

Walgrave hurried Lucy into Lady Judith’s outstretched arms, and the pair escorted Lucy to the part of the house where Colin’s siblings and cousins had gathered. Colin looked up in time to see Lucy’s back, and his face saddened. But when he turned back to his guests, he was smiling once more.

Emmeline’s stomach twisted. She wanted to throw open the window and yell Marry her instead! But she knew she’d only embarrass herself . . . and Lucy.

When Lucy had been found, drugged and held hostage to her cousin’s ambition, Em had expected Colin to call off the wedding. She’d even been relieved. But Colin had returned from London, even more committed to their impending nuptials. He wouldn’t break the engagement, nor would he—and his damned honor—let her, though she’d tried. Instead, he’d told her he’d wait, for a day, for a hundred, for however long it would take to ease her mind. And she’d realized in that moment that they would remain engaged, forever if need be, none of them happy.

Had she only refused him . . .

But it was too late for such regrets.

She looked past the chapel to the forest and open fields beyond. She had one way out. She could run.

She looked down at her walking stick ruefully. Anyone trying even half-heartedly would catch her.

Her father, Reginald, Lord Hartley, had run more successfully. He’d left one morning for a meeting in London and never returned. For months, the neighbors had speculated that, come spring, some cottager would find his remains at the bottom of the gorge. He wasn’t a man—they thought—who could bear such grief. Months later, he’d written his solicitors, directing them to forward his funds to a bank in Amsterdam. He never wrote her directly, never to her knowledge asked after her, and she, not knowing what to say, let all communication come through his solicitor.

She held her fist against the roiling in her stomach. Was this how her father had felt? Hemmed in by expectation and love? Or had he merely been the coward the townspeople called him when they thought she wasn’t listening? Deaf as well as lame, they seemed to think her, and the more she ignored the gossips, the more emboldened they became.

She caressed the head of her walking stick. Every time the gossips had called him reckless, she’d become more sober. Irresponsible, more dependable. Shameful, more upright. Until one day, they seemed to forget altogether that his blood ran through her veins as well as her mother’s. She was faithful where he had been faithless. Such a woman stood by her commitments, even those that frightened her.

If she didn’t know who she would be as Colin’s wife, she couldn’t imagine who she might be if she ran. She drew her sense of self from her land and her people. But her father had also grown up on the land, and he had run. He’d made a new life in a new country where he had no ties and no obligations. Could she?

She turned the idea over. She had her own funds through her grandfather. She could travel until the scandal died down—or forever, if she wished. She could even still travel to visit her father, simply without a husband. She’d memorized her father’s address years ago, a Venetian palazzo on the Grand Canal that he shared with his new family. Given his past, he could hardly refuse her. But he’d abandoned her once before. And if he rejected her again, what would she have lost that wasn’t already gone? The thought of running made her breathe easier than she had in weeks.

Below her window, Colin stood, still smiling, as upright a man as she’d ever met. A man she would have been proud to marry . . . before. The anxiety returned. Even if she could run, could she expose Colin to that sort of opprobrium? Could she repay his kindness with scandal? And if she became faithless once—and to her dearest friend—could she ever be found faithful again?

No matter what choice she made, someone suffered.

The bells rang out the final call to the service.

Look up, she willed him, wanting Colin to look toward her window and give her courage. Just a glance could settle her nerves. But he stood in heavy conversation with his brothers and Sam, until the duke gestured them to the chapel’s office door. She watched Sam hold open the door, watched Colin follow the duke inside, and watched the door swing shut. She imagined it thudding against the door frame as would a prison door.

The carriage yard was empty. As she was.

She waited. Jeffreys would return soon to escort her to the chapel.

Then she saw him.

A severely dressed man in a dark red tailcoat walked through the graveyard. A man who should be dead. Letting himself through the gate, he strode toward the chapel. His steady pace was more suitable to a funeral than a wedding. Inexorable, unyielding, like the progress of time.

She didn’t need to see his face to know it was Adam.

She’d watched him walk across the fields too many times.

He’d come.

But not for her.

She knew him that well, at least. No, like Lucy, he’d come to say goodbye.

But he’d come. Even if back from the grave, he had come.

Somehow that helped her to decide.

Jeffreys’s knock at the door drew her attention from the window. “Lady Emmeline, it’s time.”

“Join me, Jeffreys.” Emmeline walked slowly to her writing desk and took a seat. “I need your counsel.”