Читать книгу Jewish London, 3rd Edition - Rachel Kolsky - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеHISTORICAL OVERVIEW

The UK Jewish community currently numbers around 280,000, with approximately 70 per cent living in London. Other cities have a rich Jewish heritage but with their communities now depleted, it is in London where the buildings, associations and personalities who have shaped the community are concentrated.

The text that follows is a condensed history of Jewish London, from the 11th century to the present day.

11th–17th CENTURIES

Following the invasion in 1066, William I is credited with first inviting Jews to England when he needed to establish a system of credit. Communities were established in county capital towns such as Norwich and Lincoln but the main concentration for medieval Jewry was in London, in the area that is now the City of London. They worked as moneylenders and merchants but the community was not a ghetto. Street and church names in the City, such as Old Jewry, Jewry Street and St Lawrence Jewry serve as reminders, as no buildings remain. It was very exciting when a 13th-century Mikvah was discovered in 2001.

Edward I expelled the Jewish community in 1290, which by then had dwindled in number. During the subsequent period, known as the Expulsion, a small secret community remained. Other Jews, often doctors and lawyers, who were given royal protection, were able to reside in England more openly.

Oliver Cromwell allowed Jews to return in 1656 and, following this Resettlement, Sephardi Jews and then Ashkenazi Jews settled to the east of the City and beyond, where they established cemeteries, synagogues, businesses, hospitals and schools. By the early 1700s, the area around Aldgate was nearly 25 per cent Jewish. The wealthy soon bought palatial homes and country estates mostly to the north and south of London in Highgate, Totteridge and Morden.

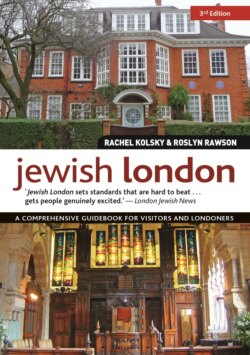

Great Synagogue plaque, Old Jewry, City of London (see here).

1800s–EARLY 1900s

The move westwards also began and an Anglo-Jewish aristocracy developed in the West End including the Rothschilds and Moses Montefiore. By the mid-1800s, branch synagogues were built in the West End and North and South London suburbs. By the 1870s all the key Jewish communal initiatives had been established including The Jewish Chronicle, Board of Guardians, Board of Deputies and the Jews’ Free School (JFS).

In the 1880s, persecution of Jews in Eastern Europe led to tens of thousands of Jewish migrants arriving in London. They lived and worked near their point of arrival in the already crowded areas of Whitechapel and Spitalfields. A Jewish population of 125,000 with 65 synagogues was contained in 5sq km (2sq miles). It became the ‘Jewish East End’, with the sweated trades of tailoring, cap- and shoemaking, but vibrant street markets, youth clubs and Yiddish theatre also thrived. This life was replicated in the smaller community of Soho and Fitzrovia in London’s West End.

To relieve overcrowding, the community was encouraged to move east to Stepney and north to Hackney, then green suburbs. There was a distinct hierarchy within the Jewish East End – moving eastwards reflected upward mobility and school and housing costs reflected this.

Hackney-born Jews did not consider themselves Jewish East Enders. Theirs was a close-knit community with several synagogues, Ridley Road street market and Hackney Downs School, which at one time was 50 per cent Jewish.

Daniel Mendoza plaque in grounds of Queen Mary College (see here).

Stamford Hill and Stoke Newington also provided an escape from the East End. In the early 1900s, the furniture industry in Shoreditch and Bethnal Green moved northwards along the transport routes to Tottenham and Edmonton and new communities were established.

MID-1900s–21st CENTURY

The interwar years saw the first big changes to the Jewish community. Affordable housing built alongside new tube lines enabled an escape from the crowded East End to semidetached suburbia. The Northern line to Golders Green and Finchley and the Central line to Gants Hill and Ilford formed two geographically distinct communities. East End synagogues closed down and new ones were established in these suburbs while businesses typically remained in East London.

Hendon Reform Synagogue (now closed), stained glass windows

The 1930s saw a new group of Jewish immigrants; Austrian and German émigrés escaping Nazi Europe. Urban, educated, professional and assimilated, they did not go east but settled in NW3 and NW6, where housing was then cheap and plentiful. They quickly replicated their shops, restaurants and more liberal form of worship. Today, there is still a large Jewish community in these areas.

Following WWII, with mass evacuation and the loss of housing, the disappearance of the Jewish East End continued. People moved to new housing estates in Essex or remained in their evacuation homes and the JFS relocated to Camden, North London. In the 1950s, additional large suburban communities were established in Northwest London such as Stanmore, Kenton and Kingsbury.

By the early 1970s, with the second generation opting for the professions rather than working in ‘the family business’, the Jewish East End was nearly at an end. Soho and Fitzrovia followed the same pattern.

The late 20th century saw membership of North-west London synagogues decrease although the concentration of Jewish London facilities remains there. A proliferation of newer suburbs was established outside London including Bushey, Elstree, Radlett and Borehamwood, with a full range of facilities.

Into the 21st century Hackney hosts the vibrant and expanding ultra-orthodox community in Stamford Hill and inner suburbs such as Brondesbury and West Hampstead are experiencing a renaissance. One aspect unites the communities: they are composed, in the main, of the children and their descendants of the East European immigrants who were at the core of the Jewish East End.