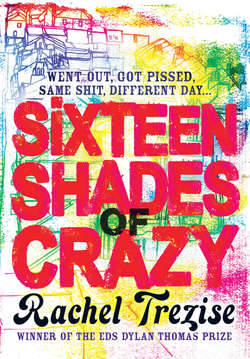

Читать книгу Sixteen Shades of Crazy - Rachel Trezise - Страница 8

3

ОглавлениеOn Monday, Ellie boarded her 7 a.m. train with the usual commuters: a middle-aged administrator at Ponty College and a bricky working down the Bay. They were the only three people awake in Aberalaw at that time in the morning. At 7.55 she alighted at Cardiff Central Station, the nearby Brains Brewery coming to life for another sun-soaked shift, the pungent stench of the hops saturating her twenty-minute speed-walk to Atlas Road. There she sat in a stifling workshop, sticking stickers on mugs while the rush hours whizzed past the yellow bricks of the city.

There was a crisis going on with the Alton Towers batch. They needed another five hundred by the end of summer but the Ceramics department couldn’t get the colour right. Ellie was bored of the stupid picture: a navy turreted castle with red fireworks in the background. The mugs were orange and the castle kept coming out purple. It was because the kiln was set at the wrong temperature. Everybody on the floor knew it. But the management were adamant it was Safia and Ellie’s fault. Jane was trying to stop them using hand cream, stop them eating crisps in case they got gunk on their fingers; all sorts of screwed-up rules it was illegal to instate. The desks were stacked with tray upon tray of orange mugs, all waiting for quality control. They even had a mini-skip in which to throw the rejects, smashing each one first in an attempt to prevent light fingers. Ellie had jokingly offered Jane a majority percentage in a spot of bent trade but Jane had threatened to report her. Jane, who was Ellie’s sister, had been the Ceramics manager for seven years. She was obnoxious to start with, but the job had pushed her to the edge. The factory floor was a breeding ground for paranoia. You had to keep watching your back because everyone around you would do almost anything to defend their own menial position, bereft of the courage to go and try something new. It was like a prison cell; the guy next to you initially appearing to be another hapless fool, then twelve months later turning into a loathsome psychopath whose face you dreamt about mutilating with a craft knife you stole from the art studio.

Safia threw a chewing gum at Ellie. It hit her on the cheekbone then landed at the bottom of her glue trough with last week’s tacky scraps of paper. Ellie fished it out and threw it back at Safia, a new layer of gloop staining the sleeve of her crisp white blouse.

Safia laughed. ‘Yous have a good weekend?’ she said. She was a tall Pakistani girl with clumpy mascara. She’d ambled into the factory and sat at Belinda’s desk, a week after Belinda had walked out. For the first five days she’d complained that the transfers sent in from the cover-coaters were too thin, or too thick, that the mugs were chipped and discoloured. Ellie’d liked Belinda because Belinda danced incessantly to the music in her headphones, ignoring everything Jane said. She’d had the words Fuck Work inscribed across the bust of her tabard. But Safia was pedantic.

One stormy Tuesday morning following a bank holiday, Safia and Ellie were the only daft cows who’d turned up for work. Forced to sit in the workshop together at lunch, chewing oily tuna sandwiches from the newsagent on the corner, Ellie reluctantly warmed to Safia’s worrisome and naive nature; the way she thought she’d never get over her first love, a U2 fan from Caerphilly. She was born and raised in Cardiff, the essence of the city audible in her nasal words. Her family had sent her to Manchester for two months during a perplexing adolescence and her mother had taken her to Pakistan once to meet her grandmother. Safia had cried to come home long before the four weeks were spent; screamed on the first day, scared shitless by lizards climbing up the living-room walls. She was struggling to balance her life between her Muslim family and extended Western social circle. A difficult situation arose every time someone mentioned going to McDonald’s for lunch or offered her a glass of white wine, endless bickering at home about trouser suits, uncomfortable conversations elsewhere about engagement rings and suntans.

Ellie shrugged now. ‘Fine,’ she said.

Safia copied the gesture contemptuously, unsatisfied with the answer.

‘Fine,’ Ellie said, again. ‘Went out, got pissed. Same shit, different day.’ She didn’t have the energy for a discussion about it. Her head was still fuzzy with the phet comedown. She hadn’t done powder for years, wasn’t used to the dizzying after-effects.

She picked a new mug from the pile and gently ran her fingertips along the circumference, feeling for imperfections. She peeled a decal from its backing and wound it around the mug, squinting at it as she ironed the air bubbles out with her tongue-shaped smoother. Gavin dropped a mug on the floor and Ellie looked up to see if it had smashed. It had, but he continued to work regardless, struggling with the direct print machine. He was a solid man with a girlfriend he didn’t like and twins on the way. He made mistakes and stuck by them, held his head high, took the bacon home. He was wearing a Cardiff City football T-shirt, the season fixtures printed on its back. It was a reject from the T-shirt department. Nobody wore their own stuff to work unless the only seconds out were England sweatshirts. She knew the fixtures now by heart. They’d both worked overtime fourteen days in a row. Gavin was saving for a double buggy and Ellie had to make-up Andy’s half of last month’s rent.

In the beginning, Ellie had been impressed by The Boobs. Andy was adamant that they were going to make it and Ellie had no reason to doubt him. Ambition was written through her own bones like a stick of Porthcawl rock. She knew what it was to want rabbling cities and hectic skylines, to have dreams about seeing the back of the valleys. So when she moved in with Andy, only to discover their joint income didn’t stretch to the lease, not even on a crumbling two-bedroom in Aberalaw, Ellie was happy to quit freelancing in favour of a steady income. She figured that when the hard work was done, she’d be one half of an über-couple, renowned for throwing vegetarian dinner parties at their chic Greenwich Village brownstone. That was over a year ago, and she felt as though she’d stuck enough stickers on mugs to last four lifetimes.

‘Bastard!’ Gavin said as another mug spun out of his grip. It shattered on the concrete floor. He bent down to retrieve the fragments, throwing each one into the mini-skip with an expletive.

‘Are you going to tell me about your weekend?’ Safia said, eyes narrowing to slits. ‘I thought Andy was coming home on Saturday.’ Safia didn’t have a social life. She spent most of her leisure time cooking pasanday for her family. She watched Coronation Street. She meticulously clung to the details of Ellie’s existence like a tabloid journalist unearthing the secrets of an A-list celebrity.

Every day, Ellie ran through an inventory of the things she’d done since she’d last seen Safia: what time she’d got home; what she’d eaten for dinner. Safia’s favourite subject was Andy. If he and Ellie had had sex, Safia needed to know the position, the point of orgasm, the colour of the sheets. Over time Ellie had begun to embellish these little narratives, so that she’d eaten scallops instead of battered cod, worn negligees instead of fleece pyjamas, got twenty minutes of cunnilingus instead of nothing. It was inevitable: Safia’s appetite for romance was insatiable, but Ellie had lived with Andy for a long time – they sometimes couldn’t be bothered to have sex. And today she wasn’t thinking about Andy at all; her mind’s eye was busy with the stranger’s image: his chaotic hair, his treacle-black eyes, his lily-white teeth.

It made something in her tummy swell, like a fist of dough in an oven. She was wondering why his girlfriend wasn’t allowed to drink vodka, wondering what his name was, wondering what the hell he was doing in Aberalaw. These little mysteries were far more compelling than anything to do with Andy, more compelling even than the idyllic fantasy life she had created for herself and conveyed on a daily basis to Safia. The stranger arrived seamlessly in her consciousness. One minute she’d been missing Andy; the next, there was some long-haired extraterrestrial who had materialized from thin air.

‘El?’ Safia said, as if from some distance.

Ellie sighed, annoyed by the interruption. She considered telling Safia about the stranger, but then quickly dismissed the idea. Safia was as chaste and delicate as the foil on a new coffee jar. She was religious. She’d been conditioned to ignore temptation, neglect her own feelings, banish any rebellious thoughts that accidentally found their way into her head. She wouldn’t understand Ellie’s predicament.

‘Yeah, Andy’s home,’ Ellie said. ‘And the band had some good news. A Radio 1 DJ liked one of their demos. He wants them to go on his show.’

‘Wow,’ Safia said. ‘They’re going to be famous!’

Behind her the fire exit opened. Jane appeared, heels clicking on the concrete. She stood next to their adjoining desks; hand on hip, counted the trays of mugs piled up from the floor. She noted the total down on her clipboard, her glasses slipping down her nose. ‘You know we need a whole new batch of these packed and shipped by the end of August, don’t you? Save your chitchat for your coffee break.’