Читать книгу Spider Eaters - Rae Yang - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

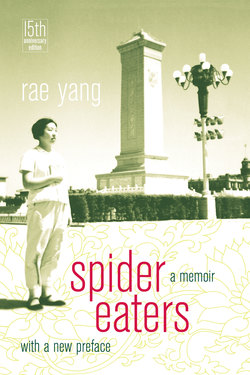

ОглавлениеPreface to the Fifteenth Anniversary Edition

It makes me sad that, forty years after the Cultural Revolution, the topic is still taboo in China. Serious discussion about this historical event, which involved millions in the 1960s and 1970s, is still unattainable.

As a result, young people born after the Cultural Revolution know next to nothing about it. When I asked my Chinese students at Dickinson College, they told me they knew about it. It was in their history book.

“What does the book say?” I asked them, surprised.

“It says: due to mistaken decision(s) made by the country's leader(s), the Cultural Revolution was a ten-year-long catastrophe.” (Here the Chinese sentence does not reveal if the nouns are singular or plural.)

“That's it?”

“That's it.”

But the Cultural Revolution I lived through was a lot more complex. It meant entirely different things for different groups of people: the élite, the small potatoes, the old, the young, those who had revolutionary families to brag about, and those whose families were condemned ... Some benefited from it. Others suffered unspeakable losses. How can it be summed up with a one-sentence conclusion?

As for those who lived through the Cultural Revolution, many have “joined the ancients.” Those who are still alive have, after four decades, either revised their memory conveniently or lost the bulk of it. The vivid details are washed away by the relentless torrent of time. Tell me about the transient nature of our memory! From my own experience now I understand.

Therefore I am glad that I began to write Spider Eaters in the early 1980s, only a few years after the Cultural Revolution was over. My memory was still fresh. For this, I should thank America, because I would never have written such a memoir and confessed that I had beaten people and raided homes in 1966, if I had stayed in China. I'd have gotten myself into big troubles. Maybe that's why, to the best of my knowledge, up till now only two former Red Guards have admitted that they beat someone. Who would understand me if I were to tell them that I committed those crimes out of my best intentions for mankind? Meanwhile, of course, I was also driven by fear. I was eager to display that I loved Chairman Mao. I tried to be more revolutionary than others.

Tom Tymozcko is the one I should really thank for this book. I would not have written it had I not met him in 1981 and had we not shared stories about our pasts. In that year I was accepted by the University of Massachusetts at Amherst as a graduate student. When the university gave me options about my housing, I chose a host family. I wanted to learn more about American culture and society. I was eager to improve my English. At that juncture, none of us Chinese students knew how long we would be allowed to stay in this country. The gate of China had just opened up.

The host family I got was a family of five. The couple was in their thirties. They had three little children. The family lived in a gigantic house on the outskirts of Northampton in Massachusetts. Tom, my host, was a professor at Smith College. It turned out that he was extremely curious about my experience in China, especially during the Cultural Revolution. That was because China had been cut off from the rest of the world for more than three decades before our group of students and visiting scholars came out.

My memory of the Cultural Revolution changed as soon as Tom and I started talking. Some episodes, forgotten a long time ago, came back to my mind. Simple conclusions I had accepted became questionable. Experiences I shared with millions grew personal when I tried to explain them to Tom. I had to look deep into my own heart and mind.

Before I left China, I was convinced that I had been a pure victim of the Cultural Revolution. For ten years, I had wasted my time in the countryside and in a factory. As a result, I never attended high school nor college. Then my mother died suddenly on January 7, 1976, one day before Premier Zhou Enlai died. The country was in chaos. No one knew what disease killed her. Two years later, my dear Aunty left us. My family fell apart. . .

But that was not what Tom wanted to hear. He told me that the baby boomers in this country were inspired by the Red Guard movement in China. When the young people here rebelled against authorities, many studied the Little Red Book, quotations of Chairman Mao. Tom was one of them.

That was the first time I heard the term “baby boomers.” I realized that the Red Guards were the baby boomers in China. When Japan surrendered in 1945, people returned home. Families were reunited. Babies were born. This trend only intensified after the civil war between the Communists and the Nationalists ended in 1949. The baby boom in China, however, came to an abrupt end in 1959 when the country was hit hard by a large-scale famine. Millions in the countryside starved to death. Everybody was hungry in the cities. The birth rate dropped precipitously. Three years later, the boom resumed. But the children born after the famine were too young to experience the Cultural Revolution. To us, they belong to a different generation.

Night after night, Tom and I talked in the kitchen of the big house. By then, dinner was over; the others had left. The room was still warm from all the cooking. Outside, white frost had fallen on the ground. All was quiet. Comparing notes about the boomers, Tom and I made amazing discoveries.

The propaganda and paranoia in the fifties had been almost the same in China and in the United States, for example. When Tom told me about this, at first I was confused and skeptical. The United States was on the opposite side of the Cold War, a beacon on the hill and flagship for freedom. How could the atmosphere be similar? Tom sensed my disbelief. But he said nothing.

The next weekend, he knocked on my door and asked if I would like to see an old movie. It was Invasion of the Body-Snatchers. What I saw in the film was so familiar. I immediately understood. The frustration they felt in the “good old days” and their desire to rebel, those were the same as ours. We would rather think with our own heads and pursue our own dreams. We resented the pressure put on us, forcing us to conform.

Later on I heard from Tom about the counterculture movement, the Kennedys, Camelot, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I have a dream” speech, the civil rights movement, the antiwar movement, the hippies, and the Beatles.

Even the big house we lived in, Tom told me, had been an experiment. Two young couples bought the house together in the early seventies. The idea was to share everything. So when the kids grew up, they would think collectively and work hard for everyone. No more private ownership and individualism. The future society should not be motivated by greed ... But in a few years, things began to fall apart. The other couple moved out. That was why Tom's family ended up with such a huge house.

This story moved my heart. The American boomers were dreamers, just like us. In the Cultural Revolution, I told Tom, our greatest ambition was actually not to build an egalitarian society or to achieve democracy in China. It was more than that. Looking back on it, I think we wanted to change human nature. No more selfishness and me, me, me. We wanted to sacrifice ourselves for the liberation of mankind. “Let a revolution erupt from the depth of our souls.” That was our slogan. To put this into practice, we gave up our privileges in big cities like Beijing and Shanghai; we volunteered to work on farms in the remote Great Northern Wilderness. But somehow the “unprecedented revolution” crumbled and failed. We all got stuck and became disillusioned. Now it seems unimaginable that once upon a time we were so passionate and serious about our dreams!

In the 1970s the American boomers moved on. Tom went to Harvard, got his doctorate and became a professor. I had to start from a master's degree ten years later. For me, however, not all was lost. By talking to Tom, I realized that I had a lot more stories to tell. My audience included other professors at UMass, Amherst College, and Mt. Holyoke. Usually after a heart-to-heart conversation, they stopped treating me as a graduate student and accepted me as a peer. For a lonely immigrant, it was lucky for me to find such kindred spirits among my professors.

The stories I told them and Tom, however, were quite selective. The exciting and funny ones, I loved to tell. The tragic ones, I was reluctant to touch. I told only a few to Tom, after he gained my trust. The truly hideous stories, I could never bring up. It was not that I wished to deceive Tom. He was such a kind and generous host. He gave me help when I needed it the most. But those stories, how could I tell them to him? I did not know how to explain why we did what we did. And I really did not want Tom to think that I was an evil person, a lunatic or a fascist.

It was then that the idea of writing this book germinated in my mind. Maybe I could reveal the dark secrets to him in a book? These secrets I had never told anyone, not my parents or my husband in China. With a book I would have the luxury of several hundred pages. I could start from my grandparents and parents. Slowly I could build a case for myself and the other Red Guards. Hopefully people would be able to understand. So I began to write some passages and hid them in my drawers.

It took me fifteen years to finish the manuscript. That was too long. I missed the tide. When this book finally came out, the market in the West was already saturated with Cultural Revolution memoirs. Worse than that, I missed the opportunity to tell Tom the truth.

After Spider Eaters was published in 1977, my professors at UMass invited me back to give a talk. During the visit, they told me that Tom had just died. It was a mysterious brain fever that destroyed him. Or maybe it was a broken heart? He got sick after his wife fell in love with another man and their marriage ended in divorce. One day he lost consciousness. He never woke up in the hospital. So the dark secrets I wanted to reveal, he was destined never to hear.

As for me, I began to teach at Dickinson College after I got my doctorate from UMass. I now fly back to China twice a year to visit my father and the Dickinson students who study abroad at Peking University during their junior year. Father is ninety years old now. But as in the past, he cares deeply about the people at the bottom of society. So he is very indignant about the corruption among government officials. At Father's new home, sometimes I meet my brother Yang Lian. He became a poet after the Cultural Revolution. He left China in 1988 and has since settled down in London. My little brother Yue remains in Beijing. We are all glad that Father has found another woman; they love each other. Life goes on. Change is inevitable. But we cannot afford to forget the past.

Rae Yang

Dickenson College, 2012