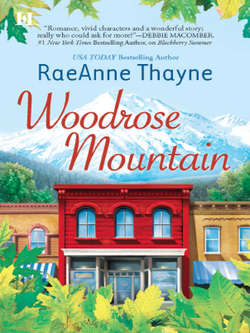

Читать книгу Woodrose Mountain - RaeAnne Thayne - Страница 7

ОглавлениеCHAPTER ONE

ON A WARM SUMMER EVENING, the homes and buildings of Hope’s Crossing nestled among the trees like brightly colored stones in a drawer—a brilliant lapis-lazuli roof here, a carnelian-painted garage here, the warm topaz of the old hospital bricks.

Evaline Blanchard rested a hip against a massive granite rock, taking a moment to catch her breath on a flat area of the Woodrose Mountain trail winding through the pines above the town she had adopted as her own.

From here, she could see the quaint old buildings, the colorful flower gardens in full bloom, Old Glory hanging everywhere. At nearly sunset on a Sunday, downtown was mostly quiet—though she could see a few cars parked in the lot of the historic Episcopalian church that had been the first brick structure in town, back when Hope’s Crossing was a hustling, bustling mining town with a dozen saloons. Probably a Sunday-evening prayer service, she guessed.

Farther away, she could see more cars and a bustle of activity near Miners’ Park and she suddenly remembered a bluegrass band was performing on the outdoor stage there for the weekly concert-in-the-park series.

Maybe she should have opted for an evening of music in the park instead of heading up into the mountains. She always enjoyed the concerts on a lovely summer night and the fun of sitting with her neighbors and friends, sharing good music and maybe a glass of wine and a boxed dinner from the café.

No, this was the better choice. As much as she enjoyed outdoor concerts, after three days of dealing with customers nearly nonstop at the outdoor art fair she had just attended in Grand Junction, she had been desperate for a little quiet.

Next to her, Jacques, her blond Labradoodle, stretched out on the dirt trail with a bored sort of air, tormenting a deerfly with the effrontery to buzz around his head.

“You don’t have any patience when I have to stop to catch my breath, do you?”

He finally took pity on the fly—sort of—and swallowed it, then grinned at her as if he had conquered some advanced Jedi Master skill. Mission accomplished, he lumbered to his big paws and looked at her expectantly, obviously eager for more exercise.

She couldn’t blame him. He had been endlessly patient during three days of sitting in a booth. He deserved a good, hard run. Too bad her glutes and quads weren’t in the mood to cooperate.

Finally she caught her breath and headed up again, keeping to a slow jog. Despite the muscle aches, more of her tension melted away with each step.

She used to love running on the beach back in California, with the sea-soaked air in her face and the thud of her jogging shoes on the packed sand and the sheer, unadulterated magnificence of the Pacific always in view.

No ocean in sight here. Only the towering pines and aspens, the understory of western thimbleberry and wild roses, and the occasional bright flash of a mountain bluebird darting through the bushes.

She was content with no sound of gulls overhead. She still loved the ocean, without question, and at times yearned to be alone on a beach somewhere while the surf pounded the shore, but somehow this place had become home.

Who would have expected that a born-and-bred California girl could find this sort of peace and belonging in a little tourist town nestled in the Rockies?

She inhaled a deep, sage-scented breath, more tension easing out of her shoulders with every passing moment. It had been a hectic three days. This was her fourth outdoor arts-and-crafts fair of the season and she had one more scheduled before September. Her crazy idea to set up a booth at summer fairs across Colorado to sell her own wares and those of the other clients of String Fever—the bead store in Hope’s Crossing where she worked—had taken off beyond her wildest dreams.

She was especially pleased, since all of the beaders participating had agreed to donate a portion of their proceeds to the Layla Parker memorial scholarship fund.

Layla was the daughter of Evie’s good friend Maura McKnight-Parker and she had been killed in April in a tragic accident that had ripped apart the peace of Hope’s Crossing and shredded it into tiny pieces.

Outdoor art-and-crafts fairs were exciting and dynamic, full of color and sound and people. But it was also hard work, especially when she worked by herself. Setting up the awning, arranging the beadwork displays, dealing with customers, running credit cards. All of it posed challenges.

Over the weekend, she’d had to deal with two shoplifters and the inevitable paperwork that resulted. This Sunday-evening run was exactly what she needed.

Finally tired, her muscles comfortably burning, she took the fork in the trail that headed back to town, her cross-trainers stirring up little clouds of dirt with every step. She’d forgotten her water bottle in her haste to get up on the cool trail after the drive and suddenly all she could think about was a long, cold drink of water.

The return trip took her and Jacques down Sweet Laurel Road, past some of the small, wood-framed older houses that had been built when the town was raw and new. She saw Caroline Bybee out watering her gorgeous flowers, her wiry gray braids covered by a big, floppy straw hat. Evie waved to her but didn’t stop to talk.

The air smelled of a summer evening, of grilling meat from a barbecue somewhere, onions being cooked in one house she passed, fresh-mown grass at another, all with the undertone of pine and sage from the surrounding mountains.

By the time she turned at the top of steep Main Street and headed past the storefronts toward her little two-bedroom apartment above String Fever, she was hungry and tired and only wanted to put her feet up for a couple of hours with a good book and a cup of tea.

String Fever was housed in a two-story brick building that once had been the town’s most notorious brothel, back in the days when this particular piece of Colorado was full of rowdy miners. She cut through an alley that opened onto the lovely little fenced garden behind the store, enjoying the sweet glow of the sunset on the weathered brick.

Jacques gave one sharp bark when she reached the gate into the garden, barely big enough for some flowers, a patch of grass and a table and four chairs where the String Fever employees took breaks or the kids of Claire Bradford—soon to be Claire McKnight—could hang out and do homework when their mother was working.

Evie really needed to think about moving into a bigger place where Jacques could have room to run. When she had moved into the apartment above the store, she’d never planned on having a dog, especially not a good-size one like Jacques. She had only intended to foster him for a few weeks as a favor to a friend who volunteered at the animal shelter, but Evie had fallen hard for the big, gentle dog with the incongruously charming poodle fur.

“Hold on, you crazy dog. You’re probably as thirsty as I am. I can let you off your leash in a minute.”

She pushed through the gate, then froze as Jacques instantly barked again at a figure sitting at one of the wrought-iron chairs. The shade of the umbrella obscured his features and her heart gave a well-conditioned little stutter at finding a strange man in her back garden.

Back in L.A., she probably would have already had one finger on the nozzle of her pepper spray and one on the last “1” in 9-1-1 on her cell phone, just in case.

Here in Hope’s Crossing, when a strange man showed up just before dark, she was definitely still cautious but not panicky. Yet.

She peered through the beginnings of pearly twilight and suddenly recognized the man—and all her alarm bells started clanging even louder. She would much rather face a half dozen knife-wielding criminals out to do her harm than Brodie Thorne.

“Evening,” he said and rose from the table, tall and lean and dark amid the spilling flowerpots set around the pocket garden.

Jacques strained against the leash, something he didn’t normally do. As she wasn’t expecting it and hadn’t had time to wrap her fingers more tightly around it, the leash slipped through and Jacques used his newfound freedom to rush eagerly toward the strange man.

The distance was short and she’d barely formed the words of the sit command before the dog reached Brodie. Given her experience with the annoying man, she braced for him to push the dog away with some rude comment about how she couldn’t keep her dog under any better control than her life, or something equally disdainful. Instead, he surprised her by scratching the dog between his Lab-shaped ears.

She didn’t want him to be kind to dogs. It was a jarring note in an otherwise unpleasant personality.

Her relationship with Brodie had gotten off to a rocky start from the moment she’d started an email friendship with his mother nearly three years ago on a beading loop, a friendship that had finally led Evie to Hope’s Crossing and String Fever, the store Katherine had opened several years ago and eventually sold to Claire Bradford.

His mother had become a dear friend. She had offered unending support and love to Evie during a very dark time and Evie adored her. She owed Katherine so much. Being polite to her abrasive son was a small enough thing, especially since Brodie had troubles of his own right now.

“Sorry. Have you been waiting long?” she asked after an awkward, jerky sort of pause.

“Ten minutes or so. I was about to leave you a note when I heard you coming down the alley.”

She didn’t feel at all prepared to talk to him, especially when she couldn’t focus on anything but her thirst. “I’m sorry, but I didn’t take my water bottle on my run and I desperately need a drink. Can you give me a minute?”

“Sure.”

“Do you want to come up or wait for me down here?”

“I’ll come up.”

On second thought, she should have phrased that differently. How about you wait here where it’s safe and stay the heck out of my personal bubble. Alas, too late to rescind the invitation now.

She led the way up her narrow staircase, aware with each step of the man following closely behind her. She wasn’t used to men in this space, she suddenly realized. Yes, she had dated a few times since she’d come to Hope’s Crossing, but nothing serious and nobody she would consider inviting up to her personal sanctuary.

For the most part, her life was surrounded by women. She worked in a bead store, for heaven’s sake, a location not usually overflowing with an overabundance of testosterone. If she wanted to date, she was going to have to put a little effort into it. Now that she almost thought she’d begun to finally achieve some level of serenity after the last rough two years, maybe it was time she did something about that.

If she were to start thinking seriously about entering that particular arena again, she could guarantee with absolute certainty that the words Brodie Thorne and dating would never appear in the same context in her head—even though he was gorgeous, if one went for the sexy, dark-haired, buttoned-down businessman type.

Which she so didn’t.

She pulled her house key out of the small zipper pocket on the inside waistband of her leggings and unlocked the door. As soon as it swung open, she winced. She had forgotten the mess she’d left behind when she headed up into the mountains immediately after her return to town—the jumble of boxes and bags and suitcases. She really ought to have left Brodie down in the garden with Jacques.

Brodie raised an eyebrow at the mess—or perhaps at her eclectic design tastes, with the mismatched furniture covered in mounds of pillows, the wispy curtains on the windows and the jeweled lampshades she’d created one winter night when she was bored. It was a far cry from her sleek little house in Topanga Canyon or her childhood home, a sprawling mansion in Santa Barbara, but she loved it.

Brodie lived in a huge designer cedar-and-glass house up the canyon high on the mountain, she remembered. She could only imagine what he must think of her humble apartment—and the fact that she could spend even an instant being embarrassed about her surroundings sparked anger at herself and completely unreasonable annoyance at him.

“Sorry. I’m in a bit of a mess. I only arrived back in town an hour ago from an art fair in Grand Junction. I’m afraid I only stopped here long enough to unload the car before Jacques and I took off for a run.”

She moved her suitcase out of the way so he could enter the living room and immediately the space seemed to shrink in half. Good thing she’d left Jacques down in the garden or she wouldn’t have room to breathe, with two big, rangy males in her small quarters.

“No problem.”

He moved inside the room but didn’t sit down. For a man who usually seemed self-assured to the point of arrogance, he seemed ill at ease for some reason. She couldn’t define why she had that impression. Maybe the sudden tension of his shoulders or some wary look in his eyes.

She swallowed and was instantly reminded of the reason she had come upstairs in the first place. She was parched. After crossing to the refrigerator in the open kitchen, she opened the door and pulled out her filtered pitcher. “Can I get you something? Water? Iced tea or a Coke?”

“I’m good.”

She closed the door and took a long, delicious drink, playing for time as much as quenching her thirst.

Why was Brodie standing in her apartment looking restless and edgy? She couldn’t begin to guess. In the year since she’d arrived in Hope’s Crossing, she’d barely exchanged a handful of terse words with him, and most of their interactions had been in some public hearing or other where she was speaking out about his latest plan to turn the charming community into a carbon copy of every other town.

A social call was completely unprecedented.

What had she done lately that might have annoyed him enough to come looking for her? She’d been too busy during the summer with the art fairs to be around town much. Maybe he was still smarting from the last time she’d taken him on at a planning commission meeting over one of his developments she considered an environmental blight.

She was painfully aware of the damp neckline of her performance T-shirt and her tight leggings, which she suddenly realized must have given him quite an eyeful of her butt as he’d followed her up the stairs.

Hiding her discomfort, she lifted her ponytail off her neck in the hot, closed air. The room felt like a sauna. She set her glass down on the counter and hurried to open a window, wishing she’d had the foresight to do that before she headed out with Jacques for the peace and cool of the mountains.

“You don’t have air-conditioning up here?”

Evie shrugged, instantly on the defensive about her employer and landlady and, most important of all, good friend. “Claire wanted to install it earlier in the summer but I wouldn’t let her. A fan in the window is usually sufficient for me on all but the hottest summer afternoons and I can always sit down in the garden if it’s too stuffy up here.”

She turned on the box fan placed in one of the three windows that overlooked Main Street. The air it blew in wasn’t much cooler but at least the movement of it served to make the room feel less stuffy.

“I’m assuming you aren’t here to discuss my ventilation issues, Brodie.”

He glanced out the window at the gathering dusk, his jaw tight, as if he were steeling himself for something particularly unpleasant, and her curiosity ratcheted up a notch.

“I want to pay for your services.”

O—kay. She blinked. The building that housed String Fever and her apartment above it had been a bordello in the town’s wilder days but she was almost positive Brodie didn’t mean that like it sounded.

She was also quite sure she should ignore the little quiver low in her belly as her imagination suddenly ran wild.

She sipped at her water again. “Did you want to commission some jewelry? Is it a gift for Taryn?”

“It’s for Taryn. But not jewelry.” Again, that hint of discomfort flashed in his expression and just as quickly, he blinked it away. “You haven’t talked to my mother, have you?”

“No. Not since before I left town Thursday.”

“Then you probably haven’t heard the news. Taryn is coming home.”

Some of her tension lifted, replaced by instant delight. “Oh, Brodie. That’s wonderful!”

She might heartily dislike the man but she could still rejoice at such terrific news, for Katherine’s sake if nothing else. “Isn’t this sudden, though? I’m stunned! Last week when your mother came into the store, she said Taryn would be at the rehab facility at least another couple of months. How wonderful for you that she’s so far ahead of schedule!”

“One would think.”

She frowned at his tone, his marked lack of excitement. “You don’t agree.”

“I would like to.”

“It’s been more than three months since the accident. Aren’t you overjoyed?”

“I’m happy my daughter is coming home. Of course I am.” His voice was clipped, his words as sharp as flat-nose pliers.

“But?”

He released a long breath and shifted his weight. “The rehab facility is basically kicking her out.”

“Kicking her out? Oh, surely not.”

“They don’t phrase it quite that bluntly. More a kindly worded suggestion that perhaps the time has come for us to seek different placement for Taryn.”

“Why on earth would they do that?”

“The rehab doctors and physical therapists at Birch Glen have reached the consensus that Taryn has reached a plateau there. She refuses to cooperate with them, to the point that she’s become unmanageable and refuses to even go to therapy anymore.”

“It’s their job to work around her plateau and take her treatment to the next level.” Nearly a decade as a physical therapist had proven that over and over. She couldn’t count the number of times she thought she had taken a patient as far as she could, had managed to push them to the limit of capability, only to discover a new exercise or stretch that made all the difference.

“Birch Glen is the most well-regarded rehabilitation facility in Colorado. As such, they have a lengthy waiting list of patients who actually want to be there and the staff would like to focus on people willing to be helped. It’s not malicious. Everyone is very sorry about the situation, blah-blah-blah. The director just gently suggested Birch Glen had helped Taryn as far as she would let them and perhaps staff members at a different facility might be better able to meet her needs at this time.”

Evie could understand that. Sometimes patients and therapists couldn’t gel, no matter how hard each side tried. “That must be aggravating for you—and especially for Taryn. I’m sorry, Brodie. I’ve heard of several excellent rehabilitation centers in the Denver area. Perhaps therapists with different personalities and techniques can find a way to challenge and motivate her.”

“We’re dealing with a fifteen-year-old girl who’s suffered a severe brain injury here. She’s not being rational.”

“Is she talking now?” Last she’d heard from Katherine, the girl was reluctant to say much since each word seemed to be a struggle.

“Her speech is coming along. Better than it used to be, anyway. Taryn has managed to communicate in her own determined way that she wants to come home. That’s it. Just come home.” He sighed. “She’s made it abundantly clear she won’t cooperate anywhere else—not even the best damn rehab unit in the country. All she wants is to come home to Hope’s Crossing.”

He showed such obvious frustration, she couldn’t help feeling sorry for him. Yes, she might dislike the man personally and, in general, find him arrogant and humorless. It was more than a little tough to reconcile those first—and second and third—impressions with the image of a devoted father who had dedicated all his resources to helping his daughter heal in the three months since the car accident that had severely injured her and killed another teen.

“Taryn’s basically throwing a temper tantrum like a three-year-old,” he went on.

“She’s been through hell.”

“Granted. And as much as I want to ignore her wishes and continue with the status quo or find her another rehab facility, I have to listen to what she’s telling us. She’s not progressing and a few of the members of her care team have suggested giving in to what she wants—bringing her home and starting a therapy program here.”

His words suddenly echoed through her mind. I want to hire your services, he had said. Suddenly, ominously, all the pieces began to click into place.

“And you’re here because?” she asked, still clinging to the fragile hope that she was far off the mark.

He looked as if he would rather be using those flat-nose pliers she’d thought of earlier to yank out his toenails than to find himself sitting in her living room, preparing to ask her a favor.

“It was my mother’s idea, actually. I’m sure you can imagine the level of care required if we truly want to bring Taryn home. For this kind of program, she’s going to need home nursing and an extensive program of rehab therapies—physical therapy, occupational therapy, speech. She still can’t—or won’t—take more than a step or two on her own and as a result of her injuries she has very limited use of her hands, especially her left one. Right now she struggles to even feed herself. Doctors aren’t sure what, if any, skills she might regain.”

Brain injuries could be cruel, capricious things. In an instant, a healthy, vibrant girl who loved snowboarding and hanging out with her friends and being on the cheerleading squad could be changed into someone else entirely, possibly forever.

He shoved his hands in his pockets. “The people at Birch Glen are telling me I really need someone to coordinate Taryn’s care. Someone who can work with all the therapists and the home-nursing staff and make sure she’s receiving everything she needs.”

Evie braced herself for him to actually come out and say the words he had been talking around. She pictured another fragile girl and those raw, terrible weeks and months after she died and everything inside Evie cried out a resounding no to putting herself through that again.

“My mother immediately suggested you as the perfect person to coordinate her care. I’m here to ask if you’ll consider it. “

And there it was. She drew in a breath that seemed to snag somewhere around her solar plexus.

“I’m a beader now,” she said tersely.

“But you’re also a licensed rehab therapist. My mother told me you even maintained Colorado certification after you moved.”

And hadn’t that been one of her more stupid impulses? She’d tested mainly as a challenge to herself, to see if she could, but also in case anyone raised objections to her volunteer work at the local senior citizens’ center. Now she deeply regretted it.

“Simply because I’m capable of doing a thing doesn’t mean I’m willing.”

Good heavens, she sounded bitchy. Why did he bring out the worst in her?

His already cool eyes turned wintry. “Why not?”

A hundred reasons. A thousand. She thought of Cassie and those awful days after her death and the hard-fought serenity she now prized above everything else.

“I’m a beader now,” she repeated. “I’ve put my former career behind me. I’ve got commitments. Besides working for Claire at the store, I’ve got several commissioned projects I’ve agreed to make, not to mention another art fair over Labor Day weekend. What you’re asking is completely impossible.”

“Nothing is impossible. That’s not just a damn T-shirt slogan.”

He rose from the couch and moved closer to her and Evie had to fight the urge to back into the fireplace mantel. “This is my daughter we’re talking about,” he growled. “After the accident, not a single doctor thought Taryn would even survive her head injuries. When she didn’t come out of the coma all those weeks, some of them even pushed me to turn off life support. No chance of a normal life, they told me. She’ll only be an empty shell. But she’s not. She’s the same stubborn Taryn inside there!”

His devotion to his child stirred her. She had to respect it—but that didn’t mean she had to allow herself to be sucked under by it.

“That isn’t what I do anymore, Brodie. Perhaps her care center can recommend someone else in the area who might help you.”

“I’ll pay whatever you want.”

He named a figure that made Evie blink. For one tiny moment she imagined splitting the amount between the scholarship fund here in Hope’s Crossing and the charitable foundation she supported in California that facilitated adoptions of difficult-to-place special needs children.

No. The cost to her would be far too great.

“I’m sorry,” she said firmly. “But I’m not part of that world anymore.”

“By choice.”

“Right. My choice.”

His eyes looked hard suddenly, glittering blue agate. “Does it mean nothing to you that a young girl needs your help? Taryn needs your help? You could change her life. Doesn’t that count for anything?”

Oh, he definitely didn’t fight fair. How could the blasted man know so unerringly how to gouge in just the exact spot under her heart to draw the most blood?

She wouldn’t let him play on an old guilt that had nothing to do with his daughter. “You’ll have to find someone else,” she said.

“What if I increase the salary figure by twenty percent?”

“It doesn’t matter how much you offer. This isn’t about money. You should really look for someone with more experience in the Colorado health system.”

Any politeness in his facade slid away, leaving his features tight and angry. “I told my mother you wouldn’t do it. I should have known better than to even ask somebody like you for help. I’m sorry I wasted my time and yours.”

And the arrogant jerk raised his ugly head. Somebody like you. What did that mean? Somebody with a social conscience? Somebody who opposed his efforts to turn the picturesque charm of Hope’s Crossing into just another cookie-cutter town with box stores and chain restaurants?

“Next time you should listen to your instincts,” she snapped.

“There won’t be a next time. You can be damn sure of that.”

He stalked toward the door, jerked it open and stomped down the stairs.

After he left, Evie pressed a hand to the sudden churn in her stomach. Only hunger, she told herself. What did she expect, when she hadn’t eaten except for a quick sandwich on the road six hours ago?

She sank down onto a chair. Not hunger. Brodie Thorne. The man made her more nervous than a roomful of tax attorneys.

Maybe she should have said yes. She adored Katherine and owed her deeply. And Brodie was right. Despite the difference in their ages, she had been friends of sorts with Taryn, who used to frequently come into String Fever before her accident, full of dreams and plans and teenage angst.

Evie wanted to help them, but how could she possibly? The cost would be far too dear. Since coming to Hope’s Crossing, she had worked hard to carve out a much healthier place than she had been in the day she had arrived, lost and grieving, wrung dry.

She knew her limitations. Hard experience was a pretty darn good teacher. She threw everything inside her at her patients—her energy, her strength, her passion. She lost all sense of professional reserve, of objectivity.

After Cassie and the emotional fallout from her death, Evie knew she didn’t belong in that world anymore, no matter whom she had to disappoint.

* * *

BRODIE HAD TO EXERT EVERY BIT of his considerable self-control to prevent himself from slamming the door behind him as he stalked down the stairway and back out to the garden behind her apartment.

His temper seethed and bubbled and he wanted to rip out a flower or two. Or every last freaking one.

Her dog—half poodle, half Labrador and all unique, just like her—woofed a quick greeting and headed for him, tail wagging. Brodie scratched the dog between the ears and released a breath, some of the tension seeping away here in the summer evening with a friendly dog offering quiet comfort.

A little of his tension. Not all of it. What the hell was he supposed to do now? Yeah, maybe it had been stupidly shortsighted of him, but despite what he had said up there, he’d never truly expected her to say no.

Ironic, really. He hadn’t wanted her involved in Taryn’s home-care program in the first place. He thought his mother was crazy when she first suggested it a few weeks ago, after the director of the Birch Glen rehab center had first rather gently suggested Taryn’s placement there might not be working out.

Evaline Blanchard was a loose screw. She kept her long, blond wavy hair wild or in braids, she favored Teva sandals to high heels, she always had some sort of chunky jewelry on that she had probably designed herself. Most of the time she wore flowing, flowery sundresses as if she was some kind of Mother Earth hippie—except when she was wearing extremely skintight exercise leggings, he amended. His body stirred a little at the memory, much to his chagrin.

He didn’t want to be attracted to Evie Blanchard. She was a bleeding heart do-gooder who seemed to spend her spare time trying to think of ways to mess with things that weren’t broken. Everything about her grated on him like metal grinding on metal.

When she first came to town, he had entertained the idea that maybe she was some kind of grifter trying to run a con on his too-trusting mother. Really, what woman in her right mind would decide to pick up and move across three states—leaving what had apparently been a lucrative rehab therapy career—on the basis of an email friendship alone?

Either she was the most patient shyster he’d ever heard of or she had genuinely moved to Hope’s Crossing for a new start. She had been in town a year and seemed to have settled in comfortably, becoming part of the community. His mother and all her friends certainly adored her, anyway.

He scratched the dog one last time, then headed out the wrought-iron gate and through the alley toward Main Street.

Evie Blanchard might not be a con artist but he still took pains to avoid her. She had a particular way of looking at a man that made him feel edgy and tense, condemned before he even opened his mouth. He knew her opinion of him. That he was a bully with a big checkbook who liked to have his way around town. He was the big, bad developer who wanted to ruin Hope’s Crossing.

Not true. He loved this town. He had made his home here, had brought his three-year-old daughter here after his hasty mistake of a marriage had fallen apart. And now he was bringing Taryn home again to heal. Didn’t that count for something?

Not to Evie Blanchard, apparently. She obviously disliked him intensely. It didn’t help that every time they had appeared on opposite sides of some planning commission meeting or public hearing or other, she would be giving some eloquent opposition to whatever he was working on and he would be appalled by the hot surge of completely inappropriate lust curling through his gut.

Of course, he couldn’t tell his mother that. He didn’t even like admitting it to himself.

He would prefer to keep a healthy distance from Evie Blanchard and her wavy blond hair and her lithe figure, which definitely filled out her tight running leggings in all the right ways.

Too bad his mother had convinced him she was absolutely the best person to help his daughter right now.

Katherine’s arguments had been persuasive, full of journal articles Evie had written a few years earlier, media reports about the amazing progress she’d made with some of her patients, even references from parents of her former clients. His mother had done her homework and had presented all her findings to him with a satisfied flourish. After reading through her dossier on Evie’s time as a physical therapist in California, he had to admit he had been impressed. Now he didn’t know if he could be satisfied with anyone else.

Brodie sighed as he headed toward his car, parked in the lot behind the Center of Hope Café. He spotted Dermot Caine, owner of the café, heading to the Dumpster out back with a garbage bag in each hand. Brodie waved and Dermot called out a greeting.

“Is it true your girl’s coming home?” the other man asked, a hopeful expression on his sunbaked features.

“That’s the plan. She still has a long way to go.” He really wished he didn’t have to add that disclaimer whenever he talked to anyone in town, but the people of Hope’s Crossing had seen enough disappointment and sorrow over the last three months. He didn’t want anyone to set unreasonably high expectations.

“You give her a big hug from me, won’t you? That little girl’s a trouper. If anything sounds good to her—one of my huckleberry pies, some of that chocolate mousse she always liked—you just say the word and I’ll personally deliver it.”

“Will do. Thanks, Dermot.” There had been a time when the owner of the diner considered Brodie nothing but a troublemaker with a chip on his shoulder. Brodie had worked hard to overcome his rep around town over the years and it was heartening to see Dermot’s concern for his daughter.

“I mean it. Everyone in town is praying for that little girl. She’s a miracle, that’s what she is, and we can’t wait to have her back.”

“I appreciate that. I’m sure Taryn does, too.”

All of Hope’s Crossing was invested in her recovery. That was a hell of a lot of pressure on a fifteen-year-old kid who couldn’t string more than a couple of words together at a time.

Brodie headed toward his SUV, a grim determination pulsing through him. Evie Blanchard was still his best hope.

He wasn’t about to give up after one measly rejection. He had never been a quitter, not in the days when he used to ski jump and had trained for the Olympics, nor in his business endeavors. He sure as hell wasn’t going to quit on his little girl.

He had failed her enough as a single father, starting with his lousy choice of her mother, who had jumped at the chance to escape them as soon as she could, leaving him with a three-year-old kid he was clueless to raise. With a great deal of help from his mother, Brodie had worked hard to give Taryn a stable life, with all the comforts any kid could want.

What he hadn’t given her was much of himself. The last few years, their relationship had been stilted and awkward, filled with fights and tantrums. He found out as she hit about thirteen that he knew diddly-squat about teenage girls and their mood swings. Somehow in all the lecturing and grounding and disappointments, he had missed the signs that Taryn had strayed dangerously off track, running with a bad crowd, drinking, even burglarizing stores.

He might have been earning a failing grade as a parent before the accident—something he was used to from his own school days—but he refused to let her down now. He was determined to find the absolute best person to spearhead her rehabilitation program on the home front. Like it or not, Evie Blanchard appeared to be that person.

So what if he found her grating and confrontational on a personal level? He was a big boy. He would get over it, especially if she could help him give his daughter her best chance at a full recovery.