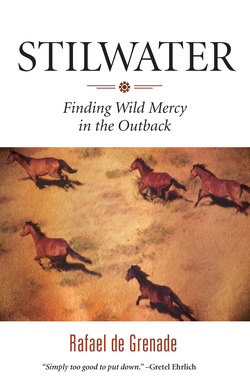

Читать книгу Stilwater - Rafael de Grenade - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеI

Gulf Country

I LANDED ON STILWATER in the dry season. I arrived by air, sweeping across white savanna mottled with sand ridges and the speckled green of vegetation. From above, the upper reach of the gulf country was a painting—tracings and patterns with vivid colors and no distinct shapes, the future and past laid out below all at once, temporal paths cut by countless spirits on walkabout, here and gone.

Trees took shape as the plane descended, tall, with blue-green willowy canopies, and then a small station rose up, a compound with a few rectangular scattered buildings, a few corrals at the end of a long white line of road leading in from the east. The pilot veered, dipping one wing, and then a long dirt strip appeared and there was no avoiding the ground. The small wheels jolted against hard-packed earth and yellow grass blurred past the windows.

When the pilot opened the curved door, I climbed down over the wing. I had arrived alone, the sole passenger. The searing white earth rose to meet me.

Australia is an island between two oceans, a landmass isolated for some fifty-five million years. Most of the twenty million people there today choose the tranquilizing lip of deep blue water at the eastern rim. But farther inland, farther north, red earth and black earth, hot savannas of eucalyptus trees and bronze desert reveal the continent’s heart. This subtle expanse reaches for days of flat nothingness, the creases of thin drainages like wrinkles of skin—parched, leathered, endless.

Hours from the cities on the coast, across the barren sweep, a horn juts upward on the northeastern corner: the spiked protrusion of the Cape York Peninsula, which reaches almost to Papua New Guinea. Here the earth begins to green again, just the palest tinge of tropics clawing onto the flattest land on earth. In its farthest domain, the horn cuts between the Arafura Sea in the Indian Ocean and the Coral Sea of the Pacific Ocean. Retreat a little to the south and west and the Arafura Sea bleeds into the Gulf of Carpentaria. Stilwater Station is a rectangle that borders the sea and covers a swath of the coastal plains.

The gulf country is alternately, and sometimes all at once, a rippling savanna, a salt flat, and a scrub whose edges endlessly change and play at the wide silk of the sea. Rivers snake across it in broadening oscillations, resisting the moment they become one with the glittering ocean, trying to slow down time. Shallow channels cut between the major conduits, where, depending on rain and the direction of storms, water can flow in either direction. Salt arms reach inward like the limbs of an octopus, their tentacles fringed in mangroves.

This land is a body without boundaries, filled with veins that transgress and regress, feeding and starving its different organs with impunity. In other places, rivers are dependable, land is dependable. This is a landscape where anything can happen. A place that defies human nature, and even seems to defy nature itself.

Few places on earth have a single tide each day, but in the gulf, two oceans collide in what feels like a conscious rebellion against physics and gravity, and the combined forces cancel a tide. Rivers flow out to the gulf for half of the day and the gulf flows into them for the other half. The tide pushes upstream, miles inland, blending salty and sweet.

The gulf is not inviting. More like luring—full of sharks and jellyfish and silver barramundi. Crocodile eyes follow any creature that ventures to the shore, but not many do. Most know to give the coastline a wide berth, and the waters ripple alone. Low tide exposes white beaches and sandbars with shallow water spreading in translucent, jade-green fi ns between them. The crocodiles sleep on the warm sand just above the surf, deadly and serene.

Inland, forested bands of sand ridges dissect the grasses and flats. Low ridges appear and disappear across the plain, sections of old waterways left a few feet higher than the surrounding country after millennia of erosion. Tall waving grasses sweep several feet high in faded gold between open forests, brackish lagoons, and murky bogs. Saltwater mangroves line the coast and saline rivers; freshwater mangroves grow on stick legs along the swamps. Water lilies raise white and purple palms in the lagoons in rare, delicate gestures. Sea wind blows in from the coast, cool on the winter mornings. Sea eagles haunt the line between sand and sea while wallabies fidget and nibble and bounce, a foot tall and easily frightened. Huge lizards—goannas—prowl the scrub and snakes trace wandering lines into the sand.

Deeper still, the forest country begins, a savanna of tall bloodwood trees, weeping coolibah, broad-leaved cabbage gums, white-trunked ghost gums, and shorter tea trees. A year turns the grass between them from a lush green to a bleached brown.

There are only two seasons here, and there is no mistaking which is which.

The wet thickens the air with heat and moisture until it bleeds into drops, the pounding monsoon storms turning the country into a hammered sheet of water—half flood, half ocean. Thundering herds of clouds give the sky more topography than the land has known for eons. As the rain falls, the sea invades as far as it can reach, and the crocodiles follow. Animals crowd onto the jungled sand ridges, which afford them only a few inches of protection above the surface of the water. Violent cyclones crack the trees, and animals huddle against the rain. Many don’t escape. Roads become impassable, and the mail plane can rarely land. Mangoes ripen and fall in rotting layers on the lawns. Heat turns viscous and the shallow sea of rain and gulf rises under the metal stilts of houses, isolating the inhabitants for months at a time.

Eventually the rains stop, and not a drop falls for nine months. Water recedes and mud hardens slowly, along with remnants of dead vegetation and animals. For a shuddering moment, the country blazes in neon green. Small flowers bloom. Then the green follows the water, receding, the sun bleaching the savanna. Grasses dry into a dead sea. Dust releases from the clay-hold, ready to scatter with any hint of wind. The sky reaches an unobstructed, piercing blue and haze rings the edges. The sun shifts imperceptibly, warmth and light losing their tone. A subtle chill invades the night. Few clouds tear against the thorny crown of stars or temper the incessant sky. Months in the dry, like those of the wet, stretch on and on, demanding either patience or surrender. All weather intercepts and seems to pass right through the skin.

When I was twelve I quit school and began working as a ranch hand on rough-country mountain ranches in Arizona. More than a decade later, when I learned of North Australian cattlemen and their strange lives on the edge of an edge, I thought that my years on horseback might have prepared me for the extremes of wilderness they call home. At the least, they sparked a longing in me for a place that was wilder and more remote than what I had known. And because I was more at home in a sleeping bag under the stars than among people and had a driving motivation to be away, beyond borders clear to me then, I decided to travel to their country.

I wrote to my great-uncle’s wife’s stepmother’s cousin, who lived in Central Queensland. Tara responded, eventually, with enthusiasm. She was pregnant with her first child, and her husband needed help in the “muster,” or roundup, of cattle. I could ride her horses and stay as long as I wanted.

I flew to Central Queensland and landed in the land of kangaroos and billabongs and coolibahs. I worked there for a month, and in exchange, the small family bought me a plane ticket to Cairns to see the Great Barrier Reef. This plane was a tiny passenger plane that serviced the Aboriginal towns in North Queensland. On the return trip I simply got off in one of these towns, Normanton, and from there kept moving north, farther toward the edges of that harsh flatland. I was female and not yet twenty-five, and I traveled alone.

The path I took would eventually lead deep into that world at the edge of wildness. It would forever crease strange lines into my skin. I made arrangements to work for a season as a ringer, or ranch hand, on a thousand-square-mile cattle station called Stilwater that lay northwest of Normanton on the Gulf of Carpentaria. Stilwater Station would be the beginning of the end of my journey.

Stilwater Station

THE PLANE WAS A SMALL PIPER that made weekly runs to several outback stations carrying mail and sometimes passengers. The desert we had just crossed still rose and fell within me as the pilot handed my backpack across, riding boots strapped to the outside. The moment I turned away, dust, heat, and light assailed my body and my mind. I stretched my neck to ease the tightening in my throat, blinked, and saw a cluster of buildings not far away. A figure in a stockman’s hat climbed out of a truck that was apparently waiting for me. This was Angus, the station manager. Short and heavy on the hoof, he ambled over and took my hand in his grip. He had a wide wrinkled face, and he eyed me with reserved suspicion.

“Angus Sheridan,” he muttered.

“My name is Rafael. Nice to meet you.”

He indicated I should get in the truck, and took a sack of mail from the pilot in exchange for a few gruff pleasantries. I turned back to watch the plane gather speed, lift, and take with it my only chance of escape. Angus did not bother to say anything more as we crossed the short distance to the station compound kitchen and Claire, the other half of management. She had wispy graying hair cropped against her neck and wore a plain blue denim shirt and skirt. She nodded and turned back inside with the mailbag Angus handed her. I would be their responsibility for a few months at least, and they had little sense for my use. I too was unclear about what I could do, so far from anything I had ever known.

Angus showed me to a small yellow house facing the lagoon at the edge of the compound—a gesture of subtle, unannounced generosity: a space to myself. I arranged my clothes in a drawer, dusted the spiderwebs, rubbed rust from the sinks with a rag, and called it home. My meager belongings didn’t even take up the space of one room in the two-room bunkhouse: boots, a few pairs of jeans, and shirts. A wooden veranda, perched just off the ground with the rest of the house to keep it above the summer floods, extended out back, overlooking the brackish lagoon.

I lay down on the old mattress, which released a faint smell of mice, and stared up at the low wooden ceiling. Faded blue paint flecked from the sheeting. Claire would be serving a meal in the kitchen, Angus had said, though at that moment I had no desire to meet any of them. I had little enough to protect me from what would happen next, and, though I had chosen to come here, I was stuck in the middle of the outback. Stilwater Station lay beyond me on all sides, reaching for what might as well have been forever in all directions. The immensity I had sought out brought nothing like solace now.

A section of coastline thirty miles long between the mouths of the Powder and Solomon Rivers defines the western boundary of Stilwater. But in summer, when the ocean moves inland and the flooding freshwater pushes a slurry of mud and land out to sea, who is to say where that line really lies? The eastern end is more clear-cut: a rusted, barbed-wire fence, worn through in places by the corrosive tea tree branches, running a semi-straight course from one river to the other.

The rivers form the other boundaries, the Powder to the south and the Solomon to the north—the S of its name a suggestion of the river’s track across the flat landscape. Stilwater lies in suspense between, its borders ephemeral as the rivers seek out more intriguing courses through the flat savanna. They loop and twist and eventually touch the gulf, two steely blue serpents, so perfect in their meandering that from the air they suggest an artist’s hand at work. Maps show them running straight courses directly to the sea. I decided that the cartographers in this country had never ventured this far; no river here had such a focus, no river in this country was so honest. The result is a hypothetical rectangle of about one thousand square miles.

Stilwater has been a cattle station as long as anyone can remember, but its history has the same ambiguous character as its borders. It was probably part of other stations at one time, and before that known by Aborigines who had better judgment than to draw straight lines across a dynamic landscape. But the British divided the territory and introduced laws of land tenure and enterprise; colonization ran its course and continued to frame existence on the continent. The land still nourished many, but it was owned as a set of resources and operated as a business for the sake of profit.

More recently, a company had used the station as a remote destination for outdoor enthusiasts and Japanese tourists. They built a large kitchen and several bunkhouses for the guests, made a few misspelled signs for the strange geometry of graded tracks across the station, and tried to make a little money off brave and foolish tourists who caught big fish and put stiff saddles on half-wild horses, then struggled to bring in a few cattle. Or so the story came to me.

Eventually they put the place up for sale, left it untended, and waited for years. Drug runners forming a link between Indonesia and Melbourne took over a few fishing camps on a secluded section of the coast and made their own dirt runway. Otherwise, most of the station was left to the wild, and the wild took it back.

At times it seems as if the farther a place is from civilization, the more people try to impose order there. The wild of the outback takes over as soon as anyone stops working. It disintegrates fences in a matter of a few years. Salt water and the oil in the tea trees turn the barbed wire into thin flaking strands, until they rust completely and become part of the soil again. Weather, rot, and termites dilapidate buildings and other structures, whole pieces of them washing away with every flood. Cyclones take down anything still standing and not rooted in deep. Cattle turn feral and old station horses run with the brumbies. Dingoes chew on the water lines. Fires scourge the dry grasslands and-sweep away all that remains.

A thousand square miles, flat but forested enough to make seeing more than a few miles impossible. This is Stilwater Station, such a definitive name for such an undefined place. I lived on Stilwater for a dry season, melded and became part of it, until I wondered if I was half salt water too.

The Sutherland Corporation purchased Stilwater a year before I arrived. Gene Sutherland was a self-made man who had created the largest privately owned, vertically integrated beef business on the continent. The Sutherlands were a sharp-thinking, hardworking, intensely loyal family. One daughter and two sons shared management responsibilities for the operations, which produced and shipped Australian beef to the far corners of the globe. They owned farms and pasture in the South, feedlots in Queensland’s Darling Downs, a meatworks, and millions of hectares in properties spread across the eastern half of the continent. Such geographic diversification of cattle properties provided more options for drought management, cattle dispersal, market flexibility, and access to export markets—meaning they made money regardless of the weather or the market.

They purchased Stilwater to make a profit. As in most enterprises, the wild corner of gulf country represented natural capital: grass grew there, which meant food could be produced to feed thousands with relatively little alteration to the landscape. But before that happened they needed to create an inventory of the stock, clean out the worst animals, and put the station back in operating order. They calculated the costs, the risks, and the needed returns, then proceeded.

No one knew how many cattle still ran on the station, but the guess was somewhere around eleven thousand. No one knew where these cattle were, or if they could still be called domesticated, but the initial plan was to take the station back and make it functional again.

The original buildings stood in the station compound along with the newer kitchen-dining complex, complete with windows and porches to admire the expansive country. Several houses and bunkhouses, an office, outbuildings, barns and shops—all in various stages of decay and disrepair—comprised the human encampment. Many of these sat on the same large lawn: the kitchen, houses belonging to the manager and head stockman, the ringers’ quarters, and a covered barbecue area; between them grew several shade trees, mangoes, and a fig. Beyond the fenced lawn, two long sheds had been constructed for a random mix of machinery that spilled over into two other equipment barns. The station had four cranes. Excess of some things and scarcity of others had yet to find the most efficient combination on the place, or maybe they just made up for each other. A diesel generator throbbed steadily to provide power.

Sutherland Corporation delivered a new tractor and paid for the repair of the old cranes and road grader. They put their personal security man in charge of hiring and firing, finding a manager, and arranging the mustering contractors.

Angus and Claire Sheridan were the first true station managers on Stilwater in more than a decade. They had lived many of their married years on an Aboriginal-owned, two-thousand-square-mile cattle station a few hours to the south along the gulf: a property that ran thirty-seven thousand cattle and took in $4 million a year. The gulf country was etched into their skin and coursed through their blood. They were perfect for the job.

They came to Stilwater Station in mango season, the dripping heat and water immediately isolating them. For six or seven months, Angus had been trying to figure out the bores—wells drilled into the artesian aquifer—and pipelines to water the cattle, the tangle of old fences, the few electric lines running off the generator, the rusting equipment, and the well-being and location of thousands of cattle.

Angus wasn’t tall, and he wasn’t thin. His forehead was engraved with a series of deep wrinkles, and he pulled his brown felt hat low over his eyes. He ambled about with a stiff gait from a previous injury, barefoot sometimes, or in sandals, with his little terrier, Frankie, not far behind. He didn’t get into the brawl and ruckus of cow work much. Instead, he tinkered with equipment, toured every road in his dusty utility vehicle, deciphered old maps and records and developed strategies for the work to be done, and tried to overlay his previous experience with the way things actually were. Once the world began to dry, his first order of business was to find a mustering crew who could handle the cow work, and a station crew to repair the infrastructure and build new fences and corrals.

The mustering crew could be hired as one mangy lot, contained and self-sufficient; they migrated like Gypsies and charged a flat daily rate for drafting, branding, and vaccinating all of the cattle on the station, and then for turning back out the keepers and shipping the rest for sale or slaughter.

Assembling the station crew, on the other hand, was a piece-meal job. Angus knew many of the free-floating men who crossed that northern swath of outback, and it was a matter of finding a few good hands who would be willing to join the operation and take on the not-so-glamorous work of general station maintenance. Angus would oversee both crews and be responsible to the station owners for their work. He would be responsible for seeing that the place eventually turned a profit.

Angus had a way of spreading out the day, making it move slowly so he could keep up with it. He drifted across the lawn from the manager’s house toward the kitchen with a slow rocking gait, carrying his flashlight, or torch, in the full dark of morning, careful as he placed his steps to miss the cane toads and slithering brown snakes. He gravitated to the same place at the table on the veranda at breakfast, midmorning smoko—a smoke and coffee break—and dinner, that old chair his throne. He had a small, white-china cup for his tea, stained with faint rings of tannins in the bottom.

Every morning he sat with Ross Porter, the new bore man, in the yellow bulb light of pre-morning for a prolonged cup of black tea and a cigarette or two while he ordered and reordered the operation in his mind. By the time he decided on the best tactic for the day, light would be turning the sky milky where it touched the horizon. He then had several hours to drive to some remote set of water troughs, or check on the cattle around lick tubs. Long solitude would swallow him, but he could arrange the hours to emerge from it in time for lunch. If he was in the office, he crossed to the kitchen again for a midmorning cuppa. Later, or sometimes earlier, when he’d had enough, he poured a rum-and-Coke and lay lengthwise on one of the couches, facing the television in the kitchen to watch the horse races.

Claire sorted the books, accounted for the details and kept the compound in order, cooking and cleaning, watering the gardens and lawns—her own way of defying the inherent wildness of the place, and drawing out elements of femininity wherever she could.

The generator kicked on at five every morning when Claire walked across the lawn beneath stars and turned on the lights in the kitchen. On most mornings she served up bacon, eggs, and stewed tomatoes and onions, setting platters out on a table in the large dining room. Knives, forks, plates, and coffee cups filled one end of the long table, and the electric hot-water pitcher, tea bags, milk, instant coffee, jam, butter, bread, and a toaster filled the other. Above the table, a picture of a sinuous river meeting the blue gulf served as a reminder of the surreality surrounding this refuge of human reality.

The crew would filter in, fill plates, and stir hot drinks in ceramic mugs. Afterward they washed their own plates and cutlery and, without rinsing off the soapsuds, dried them and placed them back on the table. Later in the morning, they filed back into the kitchen for smoko, kicking off manure- and mud-covered shoes on the veranda and walking in socks across Claire’s freshly mopped floors. They devoured her baking: Tupperwares of jam-filled biscuits, vanilla cupcakes, chocolate slice. Every evening for tea, the crew piled plates high with beef, potatoes, slices of baked pumpkin, and, on special occasions, mud crab or barramundi caught in the river or salt arms reaching inland from the sea.

Claire occupied the rest of the day with bookwork, keeping tallies of expenses on the computer database in the small office. She knew how many cattle had been shipped and the prices they might bring at market. She kept track of supplies and groceries, paychecks, mail, machine parts, medicine and supplement shipments, money in and money out.

She ordered in her mind the cluster of houses and buildings surrounded by the three-foot chain-link fence for keeping out wallabies and wild pigs. Perhaps she had the details of the place memorized already, the young mango trees, the hoses she stretched to water the lawns, the giant fig tree filled with white, screeching corellas, the palms along the fence near the kitchen.

Beyond the rivers, the neighboring station was twice as big, another to the southeast half as big, another three times as big, and Claire knew the wives of some of the other managers. They talked on the phone every so often. The dirt roads traced between them were thin lines of white chalky soil that boiled into potholes of bulldust, dropping three feet down to swallow entire trucks. The long way leading from the station to anywhere else had burned itself into her memory too. She and Angus were no strangers to the elusive nature of the outback. They both had a quality of resigned patience that would weather just about anything.

They knew that like most cattle stations, Stilwater would function as a world unto itself: mail services were provided by plane and school for the children living on the station, called School of the Air, was taught via radio. Doctors left kits of medicine coded with numbers for protection so they could make diagnoses and recommend treatment over the radio. Equipment and supplies too large or expensive to send by air came in by way of the dirt roads. Cattle were shipped out of the stations on road trains, or by rail or ship.

Angus and Claire’s job was to make the station a hive of domestic, mechanic, and livestock work, with the crew operating across the extensive territory in spokes extending from the compound. The structure of daily chores provided a framework for sanity; the livestock and waters had to be fed or checked, the crew fed at regular intervals, the lawn watered, the generator turned on and off, minor and major problems addressed. In the absence of these chores, in the absence of maintenance, disorder would rule.

Seasonal cycles offered higher order. Cattle had to be mustered and handled, some shipped away, some returned to their paddocks until another season. The wet and the dry negotiated in their turn, one leading inevitably to the other, the promise of a predictable future making life slightly easier to manage.

When cyclones smashed against the coast, the crews would wait for the storms to pass and then repair the damage. When floods stranded them for a month or two at a time, they would ration the fresh food and hunker down to wait. They understood the way place and work cultivate a culture in which humans and the environment mutually shape one another, becoming, despite the modern amenities of air conditioning, good satellite television, telephone, and Internet, two manifestations of the same entity.

Station Horses

I WOKE THAT FIRST MORNING on Stilwater to the metallic ribbons of cricket song outside the window, left open to let in night breezes as the world turned to dry. The smell of rain lingered even though it hadn’t rained and constellations receded into the deep blue of dawn. I stepped out of the bunkhouse, pausing before abandoning its cocoon to face a strange world that now included me. I turned toward the weak gleam of a porch light across the compound and risked the thin lawn and mango trees as I crossed to the kitchen in the dark. The distance was alive with possibility: slithering, thin, deadly brown snakes, taipans, black snakes, and whatever else might have sought out the cool of the grass for shelter. My toes crunched only mango leaves and one squishy brown lump, a cane toad.

As I neared the kitchen, I saw the figures of two men in the pale orange light of the veranda, seated at the small outdoor table. When I came up the stairs and into the light, Angus nodded at me. The other man, with silvery hair and a wide smile, greeted me—“How are you, sweetheart?”

“Fine, thank you.”

“The tea’s inside, hit the button on the kettle to heat up the water again; it’s been a while since it boiled.” This was Ross, the bore man, offering some hope that Angus’ gruffness wasn’t endemic to the people of this place.

When I returned with my tea to sit across the narrow table from Angus, he waited a while before saying, “We’re getting in some horses, reckon we’ll sort them out today.” He looked over at me then for a moment, assessing me in the yellow bulb light. “You ride?”

“Yes sir.”

We sat there, the three of us at a table with our cups of coffee and tea, waiting a good hour for the sky to brighten. They both seemed disinclined to learn any more than the few tattered pieces of information they had already received about me. I didn’t get more out of Angus, except that he had ordered a load of twelve horses from one of the Sutherland properties several hours to the south. The current station horses were either old, completely wild, or both.

They unloaded the new horses at the yards. A mismatched bunch if I ever saw one: a mass of manes and dust, tumbled and shaky and roughed up from jolting hours on the road. Some were monstrous animals, half draft horse, and others bony and small. All of them were stock-horse blood—thoroughbred, Arabian, and pony descendants of the earliest horses of Australia—made for distance, agility, harsh conditions, and cow work. I didn’t know whether to be enthusiastic or concerned. These were the horses that had fallen to the bottom of the barrel, scraped from other stations and trucked north to the farthest, newest Sutherland station, which had yet to gather credibility. But at the same time I didn’t feel quite so out of place as I swung the heavy pipe gates closed around the stirring, biting tangle of animals. After all, they would not have any more experience on the outfit than I did.

Angus introduced Wade Hamilton, the head stockman, who had arrived with the load of horses. Short, in his early thirties, with close-cropped dark hair and a coffee-brown stockman’s hat, he had a strong grip and a shadow of a grin. With him was Dustin, Wade’s young brother-in-law and my fellow station crew member. He was a kid, not yet eighteen, and he gave me a lop-sided smile as he stepped forward and said, “How ya goin’, mate?”

Angus indicated to Wade that he was passing off responsibility for me, and he climbed back into the ute—a utility vehicle with a cargo tray—and left us there at the corral without another word.

“Well mate,” Wade said, “let’s sort out these horses.”

He carried a saddle and saddle pad out from a shipping container serving as a tack storage that sat just beyond the pens. He swung the saddle to rest on the cross-rails of the rusty pipe fence and stepped inside the corral with a halter. Dustin and I followed into the smoke of agitated soil.

As the head stockman, Wade had first choice of the new mounts, and he didn’t waste time laying claim. He didn’t even turn to us, just quietly said, “I’ll take the white gelding and the tall bay.” We would each need a change of horses, two or three for the cow work that lay ahead.

Wade moved forward, and the horses pressed against the farther corner of the corral. “We’ll ride ’em and you can choose a couple for yourselves.”

We didn’t argue with his choices, the most handsome horses in the motley herd. I had silently chosen another two horses, but I’m unsure how they caught my eye. One was a tall dark horse, almost as regal as the bay, and the other a smaller black horse with a quiet eye. Maybe it was the same magnetism that draws people to recognize each other without having met before. I knew those were the horses I wanted to know, to approach quietly and lay a hand on the dark withers, to slip a lead rope around the neck, feel the nostrils quivering, and look into the liquid eye.

Wade stepped into the milling band and eased the white gelding apart, slipping the halter strap around his neck and leading him back to the fence to be saddled and bridled. Dustin and I opened the gate to let the others into the next corral, should the gelding get wild. Wade held the reins close to the horse’s neck as he swung into the saddle, ready for anything. The white horse arched his head and pranced the first few steps, but moved off into a fast high trot without revolt.

Wade had arrived at Stilwater a few months prior, bringing his wife, Cindy, and their two young children—Wyatt, who was five, and a newborn daughter, Lily. Wade had grown up on cattle properties in Central Queensland and spent his early life around horses and cows. He had also been a bull rider.

He’d met Cindy in the rodeo circuit—she was a professional barrel racer, and she kept her brumby-cross chestnut barrel horse close to the house to ride. Some days she took her horse and Lily out to the round yard, set her sleeping daughter in the pram, and galloped dusty circles around the innocent child. I’d heard stories of some mothers carrying their infants in slings while they mustered and hanging the babies in trees when they had to gallop off after an unruly cow. Cindy helped Claire with the cooking, pulled the sprinkler around the lawn, and started lessons with Wyatt via School of the Air, struggling like most mothers in the outback to haul her little son into the house and keep him there until he had finished his schoolwork.

Wade surveyed the horses in the pen, no doubt considering the mess he had been handed and the work that lay ahead. If he was equally uncertain about his new station crew member, he did not let on.

Dustin chose his favorites next, both younger, unsettled broncs who could give a wild ride. A rider is only as reliable as his horse, and good crew members ride good horses. I nodded.

Wade and I closed the gates behind Dustin and stood warily to the side while he saddled his first choice, the young horse’s white eye rim signaling a forthcoming explosion. Dustin had blond locks that fell from underneath his silverbelly stockman’s hat, covering his long eyelashes. He took his hat off and slicked his hair back with his hands, replaced the hat, and gathered up his reins.

Dustin swung quickly into the saddle and within two steps the horse hit the air in panic. Dustin rode him through several high jolts and came out astride, riding at an unsteady canter around the small corral.

Wade turned to me, coated in fine white dust. “Your turn, mate.”

To a rider, a horse is a second spirit, and riding is like becoming one being with two minds, two beating hearts, four legs, and two arms that must join into a seamless whole. The secret is to strive to become the horse while it yearns to become human; then the elusive ephemeral being comes into momentary existence. Imbalance between horse and rider, combined with movement, leather, and terrain, make it hard to follow a line forward. But with the right spirit, a good horse could mean I had a chance on this station.

I took a bridle and filtered into the herd, letting the horses slide past until I had the smaller, black, quiet-looking stock horse caught against the corner. He surrendered with a sideways look, a flick of the ear, and did not move as I approached, murmuring quietly, and looped the reins around his black neck and the bridle over his ears. He had a white blaze that flickered to a tip between his nostrils and he lowered his head, acquiescent. Leading him out of the herd, I nudged him to a trot in a small circle on a long rein before tying him to the fence. I carried over the pad and he waited while I swung on the saddle and eased the cinch tight.

I rubbed the roughened hair of his neck and then held a closer rein while I pressed at his muscles, slid a hand down his leg, and lifted a front hoof. Though he kept one ear pointed at me and his eye open, he didn’t flinch. I ran my hand over his withers, his straight back, his flanks. Wade had instructed us to check each horse for formation, hooves, teeth, lameness, and injuries. But, when they all turned up lame and knock-kneed, we didn’t have much choice in the matter. My two companions hadn’t seemed overly concerned about a thorough assessment anyway, not pausing for a second before they swung into the saddle.

I stepped in close to his shoulder, gathered the reins, and gripped, the fingers of one hand wound into the mane, the others on the smooth leather pommel. I placed a toe in the stirrup and swung my other foot off the ground. The first contact of seat to saddle leather, legs to ribs, fingers to leather reins, is all it takes to feel the exchange of electricity. Riding is not the domain of the mind, more an intuitive tactile engagement. The horse moved off in a walk without resistance. I took a few turns around the pen, then pressed my legs into the saddle leather and his flexing ribs until he stepped into a trot. I sat gently back and propelled him into a lope. He was quick to turn, light on the bit. He moved between gaits with agility. I pulled him to a stop several yards from Wade and said quietly, “I’ll take this one.”

I waited until Wade had ridden and affirmed both of his choices and Dustin his, then haltered the regal brown horse who had caught my eye in the beginning. He kept one ear flicked toward me, his eyes like black lakes. He blew hard through his nostrils a few times while I saddled, but once I was up, he stepped out in a long stride and eased into the movements. He was the tallest of the horses, less sensitive to the bit and my leg, but he was young and eager. I now had a set of companions with whom to face the onslaught of the days ahead.

Wade, Dustin, and I rode the rest of the horses one by one. Some were young broncs barely broke, a few were feedlot horses who could turn quickly but tripped in the deep melon holes left from the wet season, and some were old station horses who conveyed with their eyes that nothing would surprise them or prove too demanding. Even in the dust of the yards, in the rough survey of horses, subtle tinges of chemical response caught in my chest and pricked at my skin. With some horses I felt fear flooding my body, with others a more confident familiarity; some were scared and had perhaps been handled roughly or mistreated; some were obstinate, heavy; others flared their eyes and reared to get away.

We shuffled through papers that had come with the horses, a few including a photo, name, age, markings, brands, and comments by ringers who had ridden them. I took the stack of yellowing pages after Wade and, by process of elimination and the tracing of markings, found my two horses. The first stock horse’s name was Crow. His papers said he was seven years old. The tall gelding was a five-year-old named Darcy. Wade gave me two more horses whom neither he nor Dustin wanted: a massive stocky bay and a little filly. We turned the horses into a larger pen to cool down and water, then walked together, the three of us, across the corrals toward the truck they had parked by the loading chute, leaving the dust cloud behind.

Angus later brought out an old Brekelmans saddle that he’d found in the tack shed for me to ride. The dark leather had seen many years of riding, but I found each piece well riveted and sewn. The saddle was small and light like most Australian saddles, with the low, rounded, single arch where the horn would be on an American saddle. The stirrup fenders—the leather holding the stirrup—were cut wide, like an American Western saddle, and swung easily. They were burned into a polish where the last rider’s knees had rubbed.

I wanted to know the horses intimately before the muster work began, and so I caught Darcy later to ride him again. I led him out of the corrals where the new station horses still milled and tied him to the fence near the shipping container. He snorted and raised his head high, his neck stiff. He was taller than any horse I had ever ridden before, his shoulder at the level of my eyes. With his narrow withers, the saddle fit him well. I adjusted the bridle carefully, so that the rings of the snaffle bit pulled a couple of wrinkles at the corner of his mouth. Then I walked him out past the paddock gate and into the open bunchgrass clearing, took a deep breath, and swung into the saddle.

He tensed immediately, and I let him step out in long strides to release his nervous energy, riding with my legs pressed in alternate rhythmic motion against his ribs to establish control, my hands exerting light but firm pressure on the reins. He was a thunderstorm ready to roll across dry grass. I let him break into a fast trot and we covered the ground across the clearing, then passed through forest and yet another clearing in moments. A horse prefers a rider with focus, feels more comfortable if he doesn’t have to make decisions other than where to place his hooves. I chose an invisible point in the distance, feigning confidence for the sake of the dark horse beneath me, and rode straight ahead, into the unknown landscape.

I kept riding and almost didn’t return. We broke our course forward only to dodge around deep melon holes and fallen trees. The country unfurled like bolts of linen, forest and clearing, without any distinguishing characteristics or landmarks. If it were Arizona, I would have ridden for hours, climbing ridges when I needed to reset the compass of my mind or remember elements of the terrain described to me at one point or another, the internal lay of the land, maps drawn from story and memory. Here I had no such assets, no history, no stories, no outback formation.

I reined Darcy in and we stood there, quietness filling in the space around us. I would go no farther. A light wind erased our tracks in white tendrils of dust and eucalyptus leaves. If I were to die, it would take them a while to find me. I felt an unsettling in the pit of my stomach, an intuitive warning that this was not my landscape, and I had little right to be here. I shifted in the saddle to ease my discomfort and saw only the same close screen of weepy eucalyptus trees. So easy to get lost out here. Darcy flicked his ears. He was standing still anyway, the tension released from his muscles and neck. I turned back in the direction we had come and, choosing my angle carefully, let Darcy pick up speed for the ride home. I would saddle Crow and venture out another day.

Stephen Craye

MIDMORNING A FEW DAYS LATER, a stocky gentleman I didn’t recognize approached me and offered a ride around the station in his pickup truck. He had short silver hair and a beard and wore a clean, pressed, button-down shirt, jeans, and dusty leather boots. He was not tall, but his shoulders were so broad he looked as if he could have wrestled an ox to the ground, and he stood, unconcerned, with a steady and ambivalent gaze. I said I would need to ask permission to abandon my chores, wondering silently what sort of danger he might present. He indicated then that he was the boss, and I could do as he said.

“You are the security man,” I said. He was supposed to have met me when I arrived.

“Yes.”

“Nice to meet you then.” I climbed up into his white Hilux.

Stephen nodded. Then, almost apologetically: “I get busy.”

He headed east, driving past the yards into the successive waves of forest and clearing. I stared out the open window, at times able to see for a ways. After a while I became intensely aware of the security man at the wheel, guiding this foray into some reach of the station.

I overcame my sense that small talk was not his forte, and asked, “What is it that you actually do?”

His face was impassive as he replied, “I protect the family’s interests.”

He sped down the straight dirt track. The landscape around us was, I presumed, the family’s property, or a piece of it anyway. Stephen had appeared at the station apparently without notice or being noticed.

“What does that mean, exactly?”

He waited before answering. “I am in charge of overseeing all their operations.”

He continued after a while in measured, unhurried sentences. He worked directly with the owner, Gene, and his children, driving or flying to all of the many stations the family owned across two states in Australia. I gathered that his work was to haunt the remote reaches of the properties and know what was going on at all times. He was ultimately responsible for directing the overhaul of Stilwater. He was the one who had placed new managers and a new head stockman on the property.

We encountered occasional swamps, lagoons with crocodiles, and stretches of coarse grass too thick to walk through and almost unpalatable to the stock. The types of plants changed dramatically over short distances, and yet the overall look was almost the same: white slender trunks and stretches of grass, in repeating patterns.

“Can you tell me more about the owners?”

“Gene and his family?”

“Yes.”

“They are a good group.” He added, “They take care of me, and I take care of them.”

The few cows we passed threw up their heads when they saw us and disappeared into the scrub. Sarus cranes hefted up from swamp grasses on great gray-blue wings, masks pulled over their heads. Ibis clung to dead tree branches, their long hooked bills like sickles. Whistler ducks huddled at the edges of the murky waters. Wild boars rooted along the swamps, one sow with squealing piglets, one male with his head buried in the water, eating water-lily tubers and freshwater mussels. Paperbark tea trees wept along rivers and water holes while the bloodwoods bled down their shallowly ridged bark stained black with sap. Carbeen gums with white trunks and broad leaves; ghost gums with white bark and narrow leaves; ironbarks with poisonous leaves and dense heavy wood; black tea trees, low and almost bushy-topped; broad-leaf tea trees with elongated wide leaves and sparsely foliated short branches. Kapok trees grew almost naked with a few yellow flowers.

“What were you before you were a security man?”

“I was a cop. I was also a livestock inspector. I didn’t have such a benevolent reputation.”

As the hours of our station tour passed, he offered more information. He described different stations in the region and wove stories of people and families who had lived for generations in the sparsely populated wilderness, raising and stealing cattle and horses, slipping in and out of human tangles. He had a family in Cairns, a wife who waited for him through all his escapades and four sons who were better off when he was gone, he said; they were about as independent and strong-willed as he was. He preferred long intervals of solitude with short respites in the ocean air and civility of the eastern coast.

He started asking me a few questions then. Where had I worked before? What were my plans after Australia? I could see for myself, even as I began to answer his questions openly, how he gathered his information. He made me feel a sense of camaraderie, showing me his favorite places on the station, talking about his family, telling me what it was like to work alone and apart, to be a sea hawk over a long stretch of open plain. He said he knew everyone and was a friend of no one, preferring the distance afforded by an air of enigmatic malevolence. He liked Stilwater because it was the farthest away, the quietest. He liked inhabiting a world where urban laws of social interaction had no place and weren’t tolerated anyway.

We drove to a point on the Powder River where it was joined by another creek, the plain opening up suddenly into a wide tidal flux that carried jellyfish and crocodiles clear from the gulf. The water cut high along the banks, still swollen from the previous wet season. A white sandy beach and a band of trees on the opposite side separated the blue of the river from that of the sky. Stephen knew a crocodile that haunted this confluence. We crawled down the mudstone ledges sculpted with patterns of watermarks and onto an outlook of rocks that jutted into the river to look for it, but the monster never surfaced. Then Stephen drove me to another place, where a freshwater seep flowed into the brackish water. He’d seen crocs there numerous times, he said, waiting to prey on the wallabies that came down for a drink.

“Walk up quietly,” he murmured.

We did not see any crocodiles lying on the bank, so we climbed down to the water’s edge. He picked up a big stick in case of a sudden attack, though I wondered if it would only provide the beast with a bit of fiber in its lunch. I followed him to the seep, where he pointed out a carnivorous plant, lime green with sticky hairs exuding a droplet of sap, to which ants and bugs had become glued. He showed me a print in the mud—tail, body, nose, feet, and all—just under the high-tide line, with only the nose out of the water. I could see the entire story of the ambush pressed like hieroglyphs into wet clay. As soon as we had climbed the bank again and turned back to look, Stephen pointed to a crocodile that had lifted its head above the water. The croc followed us as we walked upstream along the high bank, keeping low in the murky water and surfacing one more time. Stephen called it a cheeky bastard. “Sly,” he said, “those crocs are sly.” I couldn’t believe we’d actually walked to the water.

He showed me a water hole, dammed to keep fresh water in and the inquisitive tide out. He said it had hundreds of crocs. We saw five or six lift their heads—just bulb eyes and nostrils above the water’s surface—and sink again. Long-stemmed, multiple-petalled white water lilies made the water hole seem like a Japanese tea garden, gum trees dropping long leaves toward the water, the setting serene. Then the outline of a crocodile head would appear and the water would seem suddenly murky and deadly. We headed back late in the day, churning up dust while the repeater, retransmitting a signal weakened by distance, announced itself over the CB radio.

As we neared the station compound, I asked Stephen how far we had driven.

“About two hundred kilometers.”

“Have we seen most of the station then?”

“Not even a corner.”

Stephen deposited me at the station compound with mild warning and encouragement: “They don’t get much drama out here, so they have to make their own; you’ll be fine.”

The Mustering Crew

AT THE BEGINNING OF FALL, just before I arrived, Angus had devised a plan to muster the entire station. He would start with the paddocks close to the house and bring all of the nearby cattle in to be worked—drafted, branded, vaccinated, and tick-dipped—at the house yards. This permanent set of pens for working and shipping cattle lay several miles up the road from the station compound. He would then send the mustering crew out to a middle set of yards, called Carter Yards, an hour or so away on a dirt track. They would commute from the compound each day with their motorbikes, vehicles, and horses, working the middle swath of the station. He would need a big cattle-hauling truck, called a road train, to bring the shippers—all of the cull cows, weanlings, orphan calves, steers, and old bulls—back to the station. Finally, he would send the mustering crew out to Soda Camp, a makeshift camp at the far northern reach of the station. A set of portable panels there could be made into an operable yard. The crew would have to move their camp entirely for the month or so he thought it would take them. He hoped that by the time they got out there the weanling calves, young steers, and cull cattle would be bringing in the needed income and the outlook would be favorable.

Angus found a mustering crew to begin the cow work and livestock inventory of the station—gathering, working, sorting, and shipping the cattle. A mustering crew sets up portable yards and camps and moves from paddock to paddock. They come in, they work the cattle, they leave. The head stockman of a mustering crew brings his own ringers and supplies them with food, petrol for their motorbikes, and horses, or horse feed if they bring their own. When they arrive, their world arrives with them: makeshift tents, strung-up tarps, forty-gallon drums of petrol and diesel, large stock trucks, packs of dogs, a herd of horses, motorbikes, four-wheelers, bull-catching vehicles, extra tires and wheels, long chains, short chains, saddles, guns, bridles, halters, catch ropes, bags of dog food, small generators, refrigerators, a portable sink, a portable washing machine, horse trailers—called floats—pots, pans, billycans, swags—bed rolls—unrolled on foam pads or rusty folding cots, spare batteries, truck parts, cans of fruit and vegetables, peanut butter, Vegemite, bags of white bread, and a folding table and chairs. All these items appear suddenly at the camp and then disappear when they move on. A cook usually comes along too.

On many stations, crews work with experienced efficiency, covering thousands of miles twice a year, living out with the heat and flies and remote expanses for months before returning home to other stations or small towns. But Stilwater hadn’t been properly mustered in at least a decade, and the remnant cattle included cleanskin, or unbranded, bulls ten years old, cows twice as old still wobbling along, and a mess of calves, yearlings, young bulls, and heifers—many without tags or brands and almost all, not surprisingly, feral.

Miles Carver ran the mustering crew, a large bear of a man with black hair and a thick beard. He wore coarse work shirts—usually torn or smeared with cow slobber, manure, or blood—a big hat that drooped a little in front and back with a small roll up on the sides of the brim, and heavy stockman’s boots. He was from a small town on the eastern coast, where his father had raised horses and where most people knew him, knew of him, or knew his father. Thirty-seven years old that winter, he seemed to have a good heart, and he rode good horses: a tall black stallion named Snake, and a black gelding called Reb. The mustering contractors called him “the big fella.”

Miles used his mass and brute strength to muscle through work—throwing cows around, lifting fallen cattle up by the horns, and ramming his stallion into cattle to push them through gates. His pack of scrawny, motley, kelpie-cross dogs clung close to his horse’s hock and were keen at cow work. He called them by name—“Down Killer, sit Ruby, come Roo, sit Ruby”—and he sent them slinking around milling, charging, snorting cattle with a few whistles and verbal commands. He could signal one dog to drop on his belly in the dust, another to lunge at a cow’s throat, another two to surround a deviant calf, and three to come back to his horse, clucking at them in reward. As he rode, his horse arched his neck down under the bit and Miles’ big hands imperceptibly tensioned the reins until the stallion ducked his head further, moved off sideways with a subtle pressure from spurred heels, and—followed by the ghost shadows of dogs—stepped forward toward the mob of cattle.

Alongside his impressive pack, Miles mustered a few people he knew with several months open and dogs, horses, trucks, and motorbikes of their own. Together they hauled a caravan of gear up to Stilwater. Most of them knew each other and each other’s families and had worked together before, but it was still a mishmash of a crew, some experienced, a couple thrown in out of sympathy or on a gamble.

They set up camp at the end of the lagoon in an old portable tin building called a donga. Manufactured in the shape of an L and rested up on stilts, this structure had some ten rooms and a narrow walkway. The crew quickly filled it with swags and gear, which they hung from the railing of the narrow veranda that ran the length of the building. In front they parked their vehicles, trailers, and motorbikes, and unloaded spare batteries and fuel drums. Drying pants and work shirts hung from a wire strung between the veranda posts, and three blackened tin cans full of water for tea and coffee and dishes sat on a small fire that seemed to burn perpetually.

A short distance from the quarters, the crew tied their packs of dogs—more than thirty altogether—to old machines, tractors, trailers, fences, and vehicles. Every other day each animal received a small cup of dog food, a little water, and a few scraps of meat. A couple of curly-haired lap dogs ran around the camp as pets, but the rest of the mongrel lot stayed tied up unless there was cow work to be done or a couple feral bulls that just needed some chewing.

The sky glowed a shade of orange umber when Miles drove up to the station compound one morning. I was seated at the small table on the veranda with Angus and Ross, awaiting a list of chores for the day. Miles pulled out the chair opposite me and gave a brief “morning” to the table before he sat down. I had met him briefly before, but he didn’t acknowledge me. Lamplight threw shadows from his silver hat onto his face, darkening his black beard. Ross offered coffee, but he shook his head.

“What time you reckon the road trains’ll show?”

“Early, they’re coming up from Normanton.”

Miles waited a moment before he replied. “We should have ’em ready to load.” After another silence he said, “Maybe I could use an extra hand.” The crew had mustered two paddocks and had about a thousand cattle in holding, waiting to be drafted, branded, and shipped or released. When Miles needed an extra person or two, he borrowed them from the station.

I tried not to notice the look of relief that crossed Angus’ eyes; he’d be free of me for the day. While Wade often took Dustin with him on long station runs, Angus had been finding odd jobs for me around the compound.

“That’d be fine,” he replied.

Miles rose to leave and Angus nodded for me to follow. I climbed into the rattling yellow ute with its wire dog crates on the flatbed against the cab. Starting the truck and turning on the headlights, Miles said it wouldn’t matter if I didn’t know much, I could work the gates while they hassled the mess of livestock in the yards.

He gave me a ride down to the donga, where they had a fire going, water heating in billycans to wash the breakfast dishes in a makeshift sink, laundry strung up along the veranda, and dogs everywhere. There was one other woman, tall and blond, pulling on a pair of boots.

“My name is Victoria—you can call me Vic,” she said with a white smile. The rest rose from the cluttered table or moved in and out of the lamplight, gathering a few things, passing comments. We piled into several vehicles and headed up the road to the cattle yards.

That first day, I had a hard time remembering the names of the new crew in the melee of feral cattle as I tried to maintain my place at the gates. I knew livestock from childhood, how to handle them, move and manage and predict them, and a little of the Australian traditions of stock work. But that morning all I had learned blurred and disappeared in the noise and battle, and it was a struggle to stay upright and alive. Dust stirred so thick that every breath felt like a gritty drink. Cattle bawled and moaned, agitated and distressed. Calves separated from their mothers wailed in disbelief, loneliness, and fear. Mothers called back to locate them, to reassure them, to register their protest. The commotion made a pandemonium of sound, tones that filled the air and ears and overflowed into the brain and nervous system. Gates clanged and banged and the ringers called out, swearing, urging, answering, whooping. Cattle filled pens and smashed through fences, so many that they trampled the dirt and pummeled each other and the crew.

One of the ringers, Ivan, worked near me, slamming the sliding gate of the race—or chute—shut behind a line of heifers. He was working full force; dust coated his skinny legs and arms, and his angular face. I could see only that he had three tiny gold earrings in one ear, and that he wore a T-shirt, shorts, and a once-red ball cap. We were waiting for the road trains Angus had indicated would be arriving soon, the huge trucks hired to haul loads of cattle south to the meatworks.

Ivan took a break in a spare moment to lean against the pipes of the railing and said, “I wonder where that trucker is.” He smacked a young heifer through the rails with a battered piece of poly pipe.

“Had too much goey and just kept on going,” he barked, answering his own question with a jolting laugh.

Outback truckers often took methamphetamines to conquer the enormous distances.

“Or not enough,” I said.

From Normanton alone, it was 155 miles, four hours of potholes and bulldust. Beyond that, who knew how many hours to the next biggest town? Twenty, fifty, with a load of cattle that had to be unloaded along the way to water and feed, and then loaded again, many getting injured or dying en route.

Some cattle are still driven along by a crew of horsemen for weeks, or months, just as we did in the United States before barbed wire divided the landscape. But in this tradition, called droving, the cattle have to be moved slowly enough that they can graze and not lose too much weight along the way. Entire crews of patient stockmen spend months trailing the dust of thousands of cattle from home pasture to their final destination at the meatworks. When they eventually arrive, they might be asked just to turn around and do it again in the reverse direction, taking young or new cattle to stations farther on. Most landowners afforded a half-mile track to the passing mobs of stock. Lined up, these spaces turned into what they called the long paddock. Now stockmen often lease stretches of grass along the margins of highways to fatten cattle as they pass.

Ivan worked too hard and was too familiar with cattle to be a random junkie off the street, but he didn’t have the arrogance of a horseman or the solemnity of a stockman. Another four yearlings banged into the pen, and he reached through the bars with his piece of poly pipe and whacked a couple of them on the nose to turn them into the race. The cattle spun and jumped, frantic between the metal paneling. Ahead, ringers moved them through the race into the crush—a squeeze chute—to be branded and ear-tagged. Heifers bawled as the brands hit them. One of the crew took a pair of dehorners to the small nubs on their heads.

Ivan called over his shoulder, “You get into that stuff much?” Meth, I guessed.

I responded, “Me? No. You?”

Between the crammed and bawling heifers, the dust, and the almost reckless work of directing cattle into the race, he gave a quick, unnerving, and infectious laugh, before yelling back, “I reckon, work hard, play hard, party harder.” Ivan sagged his long lean frame against the rails of the race, propping one boot up on the lowest bar. One of the heifers slammed a hoof through the bars, and he stood up. The crush gate banged open, and we stepped forward to move the heifers up the race.

The road trains finally arrived and the truckers lined up monstrous vehicles, massive semi trucks with two trailers, on the dirt road. Each deck could hold thirty cows. These rigs were called type-ones because they had five decks in all; a truck with two double-decker trailers and six decks was a type-two, and those were restricted from the highways except in Western Queensland. They looked like American rigs used to haul cattle, except that the top deck on each was open to the sky.

The crew shuffled to load the cattle bound for the slaughter-houses. Tanner, another ringer, nodded hello as I passed to take a place in the pens. A tall strong man with a drooping mustache, he worked one of the drafting gates. He walked with a stiff arched back, his broad chest thrust forward a little, and wore Wrangler jeans, black sunglasses, and a big black stockman’s hat. Sometimes, I noticed over the following weeks, he traded his black hat for a white hat, a change that seemed to match his mood. He rode a tall white horse for the cow work when he wasn’t riding his motorbike, and rolled the sleeves of his work shirts up past his elbows, as many did, his forearms thick, red-brown, and freckled.

I learned later that he had broken his back in several places riding bulls, and that he had steel pins holding his spine together, which was why he walked and perhaps why he acted the way he did. Who knew how he ended up at Stilwater? He raised his own bulls for the rodeo circuit, but maybe he needed money, or just a job out far from town, where his life might find meaning again.

Cole, who worked nearby, was shorter but just as strong, with dark curly hair. He wore work shirts cut off at the sleeves to reveal sun-browned, muscled arms, and he was so composed that I wondered if he wasn’t immune to the pandemonium. Sometimes he wore a bright purple shirt with his white stockman’s hat and wraparound sunglasses that made him stand out, though in all other ways he was the quietest. He was second in command on the mustering crew, perhaps because he was the most amiable and imperturbable.

Vic was Cole’s partner. Her leathered hands conveyed the truth of her spirit, which was fierce and emotional, though she kept the skin of her high cheekbones smooth and wore small silver earrings. She and Cole were both thirty years old and the anchors of the crew, making it more domestic and civilized than it would have been otherwise. They had a seven-year-old daughter back at home, somewhere to the east, with the child’s grandmother, along with several young thoroughbred race-horses and a house and property of their own. A licensed jockey, Vic brought her tall, well-bred horses out to do the mustering work after they had won several races and retired from the track. She had a wispy blond braid, and she exercised a mostly charming but firm tyranny over the crew. Even Miles took her opinions seriously and considered her part of the already top-heavy strata of management on the station. He was also in love with her, as was almost everyone else.

Vic took the numbers down on the small tally book, making hash marks for the cattle as they ran up the race and into the trucks. She stood by the rails, her braid tossed back and her black hat dusty.

Max worked in the pens near Vic. He was the youngest member of the mustering crew, eighteen or nineteen, lanky with close-cropped blond hair and a red face. He worked hard at times, but he was also the first to whinge or complain. Max was the first one to leap into the pen with rank bulls and chase angry cows to get them to charge him through gates and into the proper pens. He would climb the rails and drop his long legs around the back of an old cow and ride it bucking across the pen until he could scramble off and over the fence again. I once saw a cow kick him down and smash his head against a heavy metal post; he recovered his feet and slipped through the bars with a bloody nose and a swollen black eye, then returned immediately to the work.

Cattle crammed onto the decks of the large road trains. The branding furnace roared, and the truck driver and Cole used yellow electric jiggers to jam cattle up the ramp and onto the top deck of the truck. When the last skinny cow caught in the race climbed up, Tanner pushed the slide gate closed and I opened the other gate to send another ten cows into the pen and up the race. They slammed their horns against each other and blew snot. Miles loomed by the rails of the race to check each cow for a brand as she passed. If the cow lacked a brand, meaning she hadn’t ever seen the civilization of a corral, he pressed the glowing-hot branding iron to her side as long as he could before the cow jumped forward and the iron slipped, leaving a burned pattern on the hide.

I would get all of the crew’s names eventually and see how each fit into the felting of that strange fabric, but for the moment it was a hurricane of dust and holler, bellowing and bodies, stockmen and cattle and a ramp into a big semi with a double-decker trailer. The cows were loaded onto the truck and headed south, to their deaths perhaps, or to better pasture.

One cow climbed over the railing of the top deck somehow and fell more than fourteen feet. She had leaped over the gates of the pound earlier, clearing the seven-foot rails, and it had taken a few of the crew to get her back. Amazingly, after her fall from the truck, she rose up and ran away, and Miles, who didn’t seem like he would intentionally harm anything, said she could use some lead—a bullet, in other words. He thought she might be a little chewy though, with the heat and stress and all. The rest of the cattle would have a long hot ride on that narrow strip of bitumen across endless red clay, no matter the ending.

Then a cow suddenly slammed headfirst into the gate and slumped to the ground. Max stepped in and slapped her on the neck and back, but she only jerked a few times.

“Reckon she’s broke her neck?” he asked.

“Hmm,” replied Vic.

Vic grabbed the cow’s tail and Max grabbed her ears and they dragged her until she was free of the race. Vic patted the dying cow and then sat down on the animal’s rounded side to rest by the sliding gate of the race while she waited for another pen to be drafted.

Troy limped over. He was supposed to be the cook, but he didn’t seem well suited to the job. Miles had adopted him as part of the crew after a stroke left his left arm and leg impaired and sunk him into a bout of depression so severe he wouldn’t eat or speak. Miles thought the open air and work might do him some good.

Troy didn’t cook much, but he rolled cigarettes of loose-leaf tobacco and another easily distinguishable herb, hung his limp arm in a sling, and came out to the yards to slide open gates and brand cattle with his one good hand. His drooping hat almost covered his eyes. The hat had once been a good silverbelly, but now it was tattered, sagging and stained, and the rest of him had followed suit. He sat down on the dead cow beside Vic while the crew drafted a load of bulls and prepared to run them into the trucks. The monstrous, mad, testosterone-charged Brahmans almost smashed them all several times. I didn’t even try to help them load and was quick to jump the fence any time one of the beasts charged in my direction.

Smoko

WITH TWO ROAD TRAINS LOADED and the crew sweating and mad, Miles finally hollered that it was time for smoko. The ringers set down their poly pipes, turned off the branding fire, and gravitated to the shade of the old shipping container that had been dropped by the edge of the yards to serve as a tack shed. A line of dogs whined at our approach from where they had been tied up along the fence behind the shipping container. We washed our hands of dirt, sweat, blood, manure, and cow hair with the rubber hose outside the pens and slumped on metal and plastic chairs. The day had grown hot in the sudden stillness, and we sweltered there among the flies. A few of the crew pulled out plastic bags of tobacco they kept tucked in their shirt pockets and rolled cigarettes.

Miles had a beat-up tin coffee can to put the billy on, a plastic bag of cups, tea, and sugar, and a plastic bucket full of cookies that his mother had baked for him before he left the east coast with the crew. He filled the sooty can with water from the bore hose and put a match to the blower from the branding pen. He hung the can by a wire handle from a rebar over the blasting flame. When the water boiled, Miles shook a small heap of black tea leaves into the tin can and splashed a little cold water from the hose into the black liquid to get them to settle and cool off the handle. Then he carried the old tin back to the shade, where he poured dark-reddish tea, offering me a pink pannikin full of it.

The billycan was blackened on the outside from years of wood fires, and it smeared his big hand with soot. The crew drank tea with breakfast, at the midmorning break, at lunch, and sometimes in the afternoon. They even called their dinner “tea.” Miles also had a couple of thermoses that sufficed when the branding blower wasn’t around and they didn’t have the muster to light a fire.

He poured the rest of the cups.

“Tea? You like two spoons of sugar?”

“Thanks, mate,” replied Cole.

In the wake of the drafting this civility was beyond strange. But it lasted only so long.

Ivan picked up his mug and asked, “You plugged the hole in the billy?”

Miles didn’t even raise an eyebrow. “Yeah mate, with my finger.”

“The hole in the side or the bottom?”

“Both—you could braze ’em for me, mate.”

“You could get yourself another can.”

“I’ve had this one nearly ten years.”

“Just tie a new one behind the truck for a while, and it’d get beat up like that one,” Ivan retorted.

“Then it’d get covered in cow shit,” Miles said.

“That one’s seen worse, I reckon.”

Ivan tipped up the old can and poured himself another cup, mixed in a little sugar, and sat back down. We sweated there for a while, with hot black tea in pannikins, pants smeared with manure, faces and arms coated in dust, boots caked and lying heavy on the packed earth. A wind picked up, sweeping most of the flies away and veiling the cups of tea with a film of dust. Ivan smashed an ant with the bottom of his pannikin and pointed to another, carrying a huge crumb. He pinched two off the ground, laughing, and said, “Ready, set, go.” Then he set them down, and the ants scrambled off in different directions.

Max said, “They do that with cane toads, draw a circle and make bets, and the first toad out of the circle wins.”

Max threw his puppy a part of his biscuit, but she was tied to the fence nearby and couldn’t quite reach it.

The heat gave all these moments an unpleasant weight, though the prospect of heading back to the din and adrenaline of the pens was equally uninviting.

I felt weak and a little shaky, my hands trembling along with the cup. The crew didn’t seem to notice, and I took a careful breath, resting my nerves. The morning had pitched everything in me to overdrive. The bulls weighed more than a ton; the mad-eyed cows could have gutted any of us with a sideways swipe of a horn—all this surrounded by hard iron posts and constant movement, shouts, hooves, and dust.

Cattle are prey animals, and they respond to humans appropriately, as predators. There are correct positions and distances to maintain with respect to a cow, and correct timing—when to press toward a cow’s shoulder or head, when to back away, when not to look a cow in the eye, when to move back and forth to stimulate reactions in the herd. And while the madhouse of the pens had made chaos and brutality of the art of livestock handling, the same rules applied. If they were flouted, the work would never be finished, or one of the crew could be injured or worse. My old instincts told me when to leap forward and move back. For that I was grateful, but everything beyond was stimulus almost entirely unfamiliar to my being.

Miles finally gave a nod and said, “We’ve got a pen full of cows we should put through the tick dip and draft up before we finish loading.”

He tossed the butt end of a rolled cigarette, shook his empty cup upside down, and set the bucket of biscuits and cups in the front seat of the yellow ute before walking back to the pens of cattle. The rest of the crew followed.

Tick Dipping

TICK DIPPING WAS A REQUIREMENT only for cattle loaded onto a road train, but all of the cows brought to the yards went for the black swim. That afternoon, we dipped a set of five hundred cattle, running the drafted mob through the race until they plunged into a putrid trough of chemicals that was supposed to kill the small ticks they’d picked up from grazing in the bush. Any cattle leaving the station and bound for destinations across the tick-range perimeter had to be dipped and later checked. It was standard government protocol for the stations in the North.

The cattle had to swim through the chemical liquid until they reached the opposite end, where the concrete sloped up to a set of pens with concrete floors. The cows behind pressed and pushed the lead cows forward over the drop-off and into the acrid pond, and it rose in a surging splash as the line of cattle plunged in, swam across, and climbed, dripping, up the other side. They glistened black in the sun, standing on the wet concrete to dry for a few minutes.

The ringers worked the chutes behind to cut off the ends of the tail hair of the cattle headed for the tick dip. It was a process called tail-banging, to mark which had been dipped and which hadn’t and maybe save a few from being run through the brew twice. The small black handle of the bang-tail knife fit easily in the palm, and with one hand pulling the cow’s tail and finding the last joint of the tail bone, a ringer placed the blade facing up, twisted the stringy hairs around it, and pulled hard.

Miles held the knife in one hand and a fistful of tail hairs in the other. When he reached the end of the line, he nodded to Cole, who pulled the slide gate and hollered at the cattle to move forward. Ivan moved another group into the race, cramming the end cow to slide the gate shut behind her. A heap of tail hair lay on the ground like a pile of discarded wigs.

Dust stuck to the wet cattle at the far end of the trough, and the murky liquid pooled on the concrete. Another mob lunged forward, cattle jamming together and getting stuck between the narrow panels, slamming forward and backward and pushing legs out through the railing. After one group had plunged through the tick dip, dried off on the other side, and run into another pen, the ringers walked to the back of the yards to draft another.

Ivan said later he reckoned we all did as we were told because the government said so, and then because the station owners said so, and then the manager and the head stockmen and whoever reckoned he was in charge at the moment. We thought we operated under our own free will, he said, but it wasn’t that way, and the cattle took the brunt of it through no choice of their own. They tried not to, with all of their wily savanna fire. They smashed and cleared metal pipe fences, broke the welds on the rails, tore up each other and tore down wires, but in the end, most of them emerged tick-less, or at least should have.

Tanner swaggered up and down the race, checking whether each cow was full of milk or not, calling out “Wet” or “Dry.” They directed cows with full udders into a pen to be reunited with their calves after they had been drafted and branded. The dry cows would be loaded onto road trains.

Tailing the Mickies

WHEN THE DAY STARTED TO STRETCH OUT into afternoon, Miles got me to help walk the young bulls out—tailing the mickies, they called it—to the dried coastal plains to graze for a few hours. He let me ride his black gelding, Reb. The dark horse moved easily, giving his head to the bit. Miles and I rode in the lead, letting the young bulls find their way into the wide lane. A hundred yards out, we reined in and turned in our saddles to watch the slow herd. We sat on our horses in white sun in the dead swamp grass for an hour and a half while the dogs kept the mob together and the bulls had some time out of the mud and dust of the yards.

Savanna stretched in a choppy sea, and the low-angled sun leaned across scrubby paperbark tea trees. A nearly imperceptible breath of wind rolled off the gulf, gently sweeping away the dust and the daring, releasing the tension of cattle and crew. Pale grasses tossed their drooping heads among the gum trees.