Читать книгу The Third Pillar - Raghuram Rajan - Страница 7

PREFACE

ОглавлениеWe are surrounded by plenty. Humanity has never been richer as technologies of production have improved steadily over the last two hundred fifty years. It is not just developed countries that have grown wealthier; billions across the developing world have moved from stressful poverty to a comfortable middle-class existence in the span of a generation. Income is more evenly spread across the world than at any other time in our lives. For the first time in history, we have it in our power to eradicate hunger and starvation everywhere.

Yet even though the world has achieved economic success that would have been unimaginable even a few decades ago, some of the seemingly most privileged workers in developed countries are literally worried to death. Half a million more middle-aged non-Hispanic white Americans died between 1999 and 2013 than if their death rates had followed the trend of other ethnic groups.1 The additional deaths were concentrated among those with a high school degree or less, and were largely due to drugs, alcohol, and suicide. To put these deaths in perspective, it is as if ten Vietnam wars were simultaneously taking place, not in some faraway land, but in homes in small-town and rural America. In an era of seeming plenty, a group that once epitomized the American dream seems to have lost hope.

The anxieties of moderately educated middle-aged whites in the United States are mirrored in other rich developed countries in the West, though perhaps with less tragic effects. The primary source of worry seems to be that moderately educated workers are rapidly losing, or are at risk of losing, good “middle-class” employment, and this has grievous effects on them, their families, and the communities they live in. It is widely understood that job losses stem from both global trade and technological progress leading to automation of old jobs. What is less well known is technological progress has been, by far, the more important cause. As public anxiety turns to anger, radical politicians find it easier to attack visible and better understood targets like imports and immigrants. They propose to protect manufacturing jobs by overturning the liberal rules-based postwar economic order, the system that has facilitated the flow of goods, capital, and people across borders.

There is both promise and peril in our future. The promise comes from new technologies that can help us solve our most worrisome problems like poverty and climate change. Fulfilling it requires keeping borders open, in part so that these innovations and associated investments can be taken to the most underdeveloped parts of the world. The peril stems from influential communities not being able to adapt and instead impeding progress. If we are to harness technology’s promise, our values and institutions must change as innovations disproportionately empower and enrich some.

disruptive technological change

Every past technological revolution has been disruptive, prompted a societal reaction, and eventually resulted in societal change that helped us get the best out of the technology. Since the early 1970s, we have experienced the Information and Communications Technology (ICT) revolution. It built on the spread of mass computing, made possible by the microprocessor, and mass communication, enabled by the internet and the mobile phone. It now includes technologies ranging from artificial intelligence to quantum computing, touching and improving areas as diverse as international trade and gene therapy. The effects of the ICT revolution have been transmitted across the world by increasingly integrated markets for goods, services, capital, and people. Every country has experienced disruption, punctuated by dramatic episodes like the Global Financial Crisis in 2007–2008 and the accompanying Great Recession. We are now seeing the reaction in populist movements of the extreme Left and Right. What has not happened yet is the necessary societal change, which is why so many despair of the future. We are at a critical moment in human history, when wrong choices could derail human economic progress.

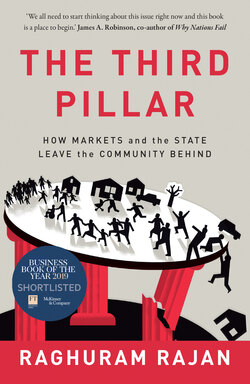

This book is about the three pillars that support society and how we get to the right balance between them again so that society continues to prosper. Two of the pillars I focus on are the usual suspects, the state and markets. Many forests have been consumed by books on the relationship between the two, some favoring the state and others markets. It is the neglected third pillar, the community—the social aspects of society—that I want to reintroduce into the debate. When any of the three pillars weakens or strengthens significantly, typically as a result of rapid technological progress or terrible economic adversity, the balance is upset and society has to find a new equilibrium. The period of transition can be traumatic, but society has succeeded in rebalancing repeatedly in the past. The central question in this book is how we restore the balance between the pillars once again in the face of ongoing disruptive technological change.

I will argue that many of the economic and political concerns today across the world, including the rise of populist nationalism and radical movements of the Left, can be traced to the diminution of the community. The state and markets have expanded their powers and reach in tandem, and left the community relatively powerless to face the full and uneven brunt of technological change. Importantly, the solutions to many of our problems are to be found in bringing dysfunctional communities back to health, not in clamping down on technology or on markets. This is how we will rebalance the pillars at a level more beneficial to society and preserve the liberal market democracies many of us live in.

definitions

To avoid confusion later, let us get over the tedious but necessary issue of definitions quickly. Broadly speaking, the state in this book will refer to the political governance structure of a country, usually the federal government. In addition to the executive branch, the state will also include the legislature and the judiciary.

Markets will include all private economic structures facilitating production and exchange in the economy. The term will encompass the entire variety of markets, including the market for goods and services, the market for workers (the labor market), and the market for loans, stocks, and bonds (the capital or financial market). It will also include the main actors from the private sector, such as businesspeople and corporations.

According to the dictionary, a community “is a social group of any size whose members reside in a specific locality, share government, and often have a common cultural and historical heritage.”2 This is the definition we will use, with the neighborhood (or the village, municipality, or small town) being the archetypal community in modern times, the manor in medieval times, and the tribe in ancient times. Importantly, we focus on communities whose members live in proximity—as contrasted with virtual communities or national religious denominations. We will view local government, such as the school board, the neighborhood council, or town mayor, as part of the community. A large country has layers of government between the federal government (part of the state) and the local government (part of the community). In general, we will treat these layers as part of the state. Finally, we will use the terms society, country, or nation interchangeably as the composite of the state, markets, communities, people, territory, and much else that compose political entities like China or the United States.

why the community still matters

Definitions done, let us get to substance. For early humans the tribe was their society—their state, markets, and community rolled into one. It was where all activities were conducted, including the rearing of children, the production and exchange of food and goods, and the succor of the ill and the elderly. The tribal chief or elders laid down the law and enforced it, and commanded the tribe’s warriors in defense of their lands. Over time, as we will see in Part I of the book, both markets and the state separated from the community. Trade with more distant communities through markets allowed everyone to specialize in what they were relatively good at, making everyone more prosperous. The state, aggregating the power and resources of the many communities within it, not only set common regulations for markets but also enforced the law within its political boundaries, even as it defended the realm against aggressors.

Markets and the state not only separated themselves from the community over time, they also steadily encroached on activities that strengthened bonds within the traditional community. Consider some functions the community no longer performs. In frontier communities, neighbors used to help deliver babies; today most women check into a hospital when they feel the onset of childbirth. They prefer the specialist’s expertise to their neighbor’s friendly but amateurish helping hand. The community used to pitch in to rebuild a household’s home if it caught fire; today the household collects its fire insurance payment and hires a professional builder. Indeed, given the building codes in most developed countries, it is unlikely that a home reconstructed by neighbors would be legal.

However, the community still plays a number of important roles in society. It anchors the individual in real human networks and gives them a sense of identity; our presence in the world is verified by our impact on people around us. By allowing us to participate in local governance structures such as parent-teacher associations, school boards, library boards, and neighborhood oversight committees, as well as local mayoral or ward elections, our community gives us a sense of self-determination, a sense of direct control over our lives, even while making local public services work better for us. Importantly, despite the existence of formal structures such as public schooling, a government safety net, and commercial insurance, the goodness of neighbors is still useful in filling in gaps. When a neighboring engineer tutors our son in mathematics in her spare time, or the neighborhood comes together in a recession to collect food and clothing for needy households, the community is helping out where formal structures are inadequate. Given the continuing importance of the community, healthy modern communities try to compensate for the encroachment of markets and the state with other activities that strengthen community ties, such as social gatherings and neighborhood associations.

Economists Raj Chetty and Nathaniel Hendren attempt to quantify the economic impact of growing up in a better community.3 They examine the incomes of children whose parents moved from one neighborhood into another in the United States when the child was young. Specifically, consider neighborhood Better and neighborhood Worse. Correcting for parental income lets the average incomes of children of longtime residents when they become adults be one percentile higher in the national income distribution in neighborhood Better than it is in neighborhood Worse. Chetty and Hendren find that a child whose parents move from neighborhood Worse to Better will have an adult income that is, on average, 0.04 percentile points higher for every childhood year it spends in Better. In other words, if the child’s parents move when it is born and they stay till it is twenty, the child’s income as an adult will have made up 80 percent of the difference between the average incomes in the two neighborhoods.

Their study suggests that a child benefits enormously by moving to a community where children are more successful (at least as measured by their future income). Communities matter! Perhaps more than any outside influence other than the parents we are born to, the community we grow up in influences our economic prospects. Importantly, Chetty and Hendren’s finding applies for a single child moving—movement is not a recipe for the development of an entire poor community. Instead, the poor community has to find ways to develop in situ, while holding on to its best and brightest. It is a challenge we will address in the book.

There are other virtues to a healthy community. Local community government acts as a shield against the policies of the federal government, thus protecting minorities against a possible tyranny of the majority, and serving as a check on federal power. For example, sanctuary communities in the United States and Europe have resisted cooperating with national immigration authorities in identifying and deporting undocumented immigrants.

Although no country can function if every community picks and chooses the laws they will obey, we will see that some devolution of powers to the community can be beneficial, especially if there are large differences in opinion between communities so that centralized “one-size-fits-all” solutions do not work.

Furthermore, community-based movements against corruption and cronyism prevent the leviathan of the state from getting too comfortable with the behemoth of big business. Indeed, as we will see in the book, healthy communities are essential for sustaining vibrant market democracies. This is perhaps why authoritarian movements like fascism and communism try to replace community consciousness with nationalist or proletarian consciousness.

In sum, the proximate community is still relevant today, even in cosmopolitan cities where ties of kinship and ethnicity are limited, and even in individualistic societies like those of the United States and Western Europe. Once we understand why community matters, and that people who value staying in their community are not very mobile, it becomes clear that it is not enough for a country to experience strong economic growth—the professional economist’s favorite measure of economic performance. Since such people cannot abandon their community easily to move to work where growth occurs, they need economic growth in their own community. If we care about the community, we need to care about the geographic distribution of growth, and about “place-based” economic policies that affect that distribution.

What then is the source of today’s problems? In one word, imbalance! When the three pillars of society are appropriately balanced, society has the best chance of providing for the well-being of its people. The modern state ensures physical security, as it always has, but also tries to maintain fairness in economic outcomes, which democracy demands. To do this, the state tries to enable most people to participate on equal terms in markets, while buffering them against their fluctuations. It may also set limits on markets. The competitive markets provide people innovative products and abundant choice. Competition ensures that those who succeed in it are efficient and produce the maximum output with the resources available. The successful have both wealth and some independence from the state, thus they have the ability to check arbitrary actions by the state. Finally, the people in industrial democracies, engaged in their communities and thereby organized socially and politically, enforce the necessary separation between markets and the state through their democratic voice. They do so because they want sufficient political and economic competition that the economy does not descend into authoritarianism or cronyism.

Society suffers when any of the pillars weakens or strengthens overly relative to the others. Too weak the markets and society becomes unproductive, too weak a democratic community and society tends toward crony capitalism, too weak the state and society turns fearful and apathetic. Conversely, too much market and society becomes inequitable, too much community and society becomes static, and too much state and society becomes authoritarian. A balance is essential!

why the community has weakened

The pillars are seriously unbalanced today. Communities have been especially impacted. In the United States, minority and immigrant communities were hit first by joblessness, which led to their social breakdown in the 1970s and 1980s. In the last two decades, communities in small towns and semirural areas, typically white, have been experiencing a similar decline as large local manufacturers close down. Often, this results in the loss of comfortable middle-income jobs held by the moderately educated. Families have been tremendously stressed, with an increase in divorces, teenage pregnancies, and single-parent households. In turn, these have led to a deterioration in the environment for children, resulting in poor school performance; high dropout rates, the increased attractiveness of drugs, gangs, and crime; and persistent youth unemployment. The opioid epidemic is just one symptom of the hopelessness and despair that accompanies the breakdown of once-healthy communities.

The technological revolution has been disruptive even outside such economically distressed communities. It has increased the wage premium for those with better capabilities significantly, with the most capable employed by high-paying superstar firms that increasingly dominate a number of industries. This has put pressure on upper-middle-class parents to secede from economically mixed communities and move their children to schools in richer, healthier communities, where they will learn better with other well-supported children like themselves. The poorer working class are kept from following by the high cost of housing in the tonier neighborhoods. Their communities deteriorate once again, this time because of the secession of the successful. Technological change has created that nirvana for the upper middle class, a meritocracy based on education and skills. Through the sorting of economic classes and the decline of the mixed community, however, it is also becoming a hereditary one, where only the children of the successful succeed.

The rest are left behind in declining communities, where it is harder for the young to learn what is needed for good jobs. Communities get trapped in vicious cycles where economic decline fuels social decline, which fuels further economic decline . . . The consequences are devastating. Alienated individuals, bereft of the hope and the feeling of belonging that comes from being grounded in a healthy community, become prey to demagogues on both the extreme Right and Left, who cater to their worst prejudices.

When the proximate community is dysfunctional, alienated individuals need some other way to channel their need to belong.4 Populist nationalism offers one such appealing vision of a larger purposeful imagined community—whether it is white majoritarianism in Europe and the United States, the Islamic Turkish nationalism of Turkey’s Justice and Development Party, or the Hindu nationalism of India’s Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh.5 It is populist in that it blames the corrupt elite for the condition of the people. It is nationalist in that it anoints the native-born majority group in the country as the true inheritors of the country’s heritage and wealth. Populist nationalists identify minorities and immigrants—easily identifiable targets and the supposed favorites of the elite establishment—as usurpers, and blame foreign countries for keeping the nation down. These fabricated adversaries are necessary to the populist nationalist agenda, for there is often little else to tie the majority group together.

While the populist nationalists raise important questions, the world can ill afford their shortsighted solutions. Populist nationalism will undermine the liberal market democratic system that has brought developed countries the prosperity they enjoy. Within countries, it will anoint some as full citizens and true inheritors of the nation’s patrimony while the rest are relegated to an unequal, second-class status. It risks closing global markets down just when these countries are aging and need both international demand for their products and young skilled immigrants to fill out their declining workforces. It is dangerous because it offers blame and no real solutions, it needs a constant stream of villains to keep its base energized, and it moves the world closer to conflict rather than cooperation on global problems.

reviving communities

Schools, the modern doorway to opportunity, are the quintessential community institution. The varying qualities of schools, largely determined by the communities they are situated within, dooms some youth while elevating others. When the pathway to entering the labor market is not level, and steeply uphill for some, it is no wonder that people feel the system is unfair. The way to address this problem, and many others in our society, is not primarily through the state or through markets. It is by reviving the community and having it fulfill its essential functions, such as schooling, better. Only then do we have a chance of reducing the appeal of radical ideologies.

We will examine ways of doing this, but perhaps the most important is to give the power that markets and the state have steadily taken away back to the community. Historically, as markets became integrated within the nation, power migrated to the national capital, with the federal government usurping community powers in order to harmonize regulations across domestic communities—after all, no manufacturer wants to have to deal with different regulatory standards each time his product crosses a community border. As markets have become global, sovereign powers have similarly become constrained by international treaties or have migrated away from nations into international bodies like the European Union. Once again the intent is to allow global firms and markets to function seamlessly across political borders.

We must reverse this to the extent possible. Unless absolutely essential, power should devolve from international bodies back to countries. Furthermore, within countries, power and funding should devolve from the federal level to the communities. Fortunately, the automation of procedures will help market participants, such as firms, cope at relatively low cost with the ensuing diversity of regulations. Moreover, easier communication and better data will allow both the federal government as well as people in the community to monitor how local government uses its new powers and funding. If effected carefully, this decentralization will preserve the benefits of global markets while allowing people more of a sense of self-determination. Localism—in the sense of centering more powers, spending, and activities in the community—will be one way we will manage the disorienting tendencies of global markets and new technologies.

inclusive localism

Instead of allowing people’s natural tribal instincts to be fulfilled through populist nationalism, which combined with national military powers makes for a volatile cocktail, it would be better if they were slaked at the community level. One way to accommodate a variety of communities within a large diverse country is for it to embrace an inclusive civic definition of national citizenship—where one is a citizen provided one accepts a set of commonly agreed values, principles, and laws that define the nation. It is the kind of citizenship that Australia, Canada, France, India, or the United States offer. It is the kind of citizenship that the Pakistani-American Muslim, Khizr Khan, whose son died fighting in the United States Army, powerfully reminded the 2016 Democratic National Convention of, when he waved a copy of the United States Constitution—for it defined his citizenship and was the source of his patriotism.

Within that broad inclusive framework, people should have the freedom to congregate in communities with others like themselves. The community, rather than the nation, becomes the vehicle for those who cherish the bonds of ethnicity and want some cultural continuity. Of course, communities should be open so that people can move in and out if they wish. Some will, no doubt, prefer to live in ethnically mixed communities while others will choose to live with people of their own ethnicity. They all should have the freedom to do so. Freedom of association, with active discrimination prohibited by law, has to be the future of large diverse countries. We will eventually learn to cherish the other, but till then let us live peaceably, side by side if not together.

Markets too must become more inclusive. Large corporations dominate too many markets, increasingly fortified by privileged possession of data, ownership of networks, and intellectual property rights. Credentialed licensed professionals dominate too many services, preventing competition from those who do not have the requisite licenses (one reason friendly neighbors cannot help rebuild a house today). In every situation, we must locate barriers to competition and entry and remove them so that opportunity is available to all. Thus, as we strive for an inclusive state and inclusive markets, which embed the empowered community, we will achieve an inclusive localism. This will enable community revival and a desirable rebalancing of the pillars.

What of truly distressed communities? Is revival even possible? Consider the community of Pilsen on the southwest side of Chicago, a few miles from my home. This once terribly damaged community is now turning a corner.

A Real Community Pulling Itself Up

Pilsen used to be populated by Eastern European immigrants, working in manufacturing establishments around Chicago. Since the middle of the last century, Hispanic immigrants and African Americans moved in steadily, and the Eastern Europeans moved out.6 In 2010, Hispanics or Latinos made up 82 percent of the population, and African Americans 3.1 percent. Non-Hispanic whites composed 12.4 percent of the population in 2010, up from 7.9 percent in 2000.

Pilsen is poor, with median household income averaged over 2010–2014 at $35,100, about half that of metropolitan Chicago as a whole. It has an unemployment rate of nearly 30 percent averaged over 2010–2014. Over 35 percent of individuals over twenty-five have not graduated from high school. Only 21.4 percent of individuals over twenty-five have a bachelor’s degree, less than half the comparable ratio in the overall US population. Nearly half of renters or homeowners have housing costs that account for more than 30 percent of their income. Keeping people in their homes is essential for community stability, and Pilsen has a hard time of it.

Low education, low incomes, and high unemployment are a recipe for drugs, alcohol, and crime. Pilsen was truly a war zone. At its peak in 1979, there were 67.4 murders per 100,000 residents in Pilsen, over double the wider city rate. In comparison, Western Europe averages a murder rate of about 1 per 100,000 per year. As recently as 1988, a Chicago Tribune reporter counted twenty-one different gangs along a two-mile stretch on the main 18th Street thoroughfare.

Yet Pilsen is a community that is trying to pull itself up. One sign it is succeeding is that the murder rate has been significantly below the overall Chicago rate for a number of years since the early 2000s, exceeding it slightly only every few years. As we will see, communities typically do not pick themselves up spontaneously—leaders emerge to coordinate the revival. Among those driving Pilsen’s revival is Raul Raymundo, the CEO of the Resurrection Project, a nongovernmental organization whose motto is “Building relationships, creating healthy communities.” Raul came to the United States from Mexico as a seven-year-old immigrant, went to Benito Juarez High School in Pilsen, attended college (including some time in graduate school at the University of Chicago), and started helping out in the community. He found his vocation after the murder of a young man just outside his church, when his pastor asked the congregation what the community was going to do about it. Answering the call, Raul and a few others started the Resurrection Project, with $5,000 each from six local churches. When the candidate they found to head the project declined to take the job, Raul stepped in, and he is still there, after twenty-seven years. Today, the Resurrection Project has funneled over $500 million in investment into the community.

As with other revival projects, the community first undertook an inventory of its assets to figure out what it could build around. It had its churches that would provide moral, vocal, and financial support for any revival, it had decent schools, it had a strong Mexican-American community with tightly knit families, and it was in Chicago, a city that goes through ups and downs but is still one of America’s great cities.

The first order of action was to engage the community to make it more livable, which meant keeping the locality clean, ridding the streets of crime, and strengthening the schools. Residents were organized to hound the city sanitation department to do their job—clean the streets and collect garbage. People were urged to form block clubs and ad hoc groups against crime. They would walk out of their houses when they saw suspicious activity so as to crowd the criminals out, or jointly call the police so that the criminals would not know who to blame. The community campaigned successfully for a moratorium on city liquor licenses in Pilsen, got some especially problematic bars closed down, and worked with police, churches, and absentee landlords to target and close down known gang houses.7 Remedial education, after-school extracurricular programs, and job-training programs increased, enabling young people to get more from their schoolwork, and giving them a ladder to jobs. Parents were urged to get involved in the schools, and they did. New school programs started—one example is the Cristo Rey Catholic School, which aims to give its students a quality education, while keeping it affordable. Cristo Rey got local businesses to pay the school fees of students. As partial repayment, each student worked one day a week for their sponsoring business. The student attended school the other four days, getting both a good education and work experience each week.

Virtuous cycles started emerging. As some older gang members turned to legitimate business, their prosperity inspired other gang members to develop skills other than the ability to inflict violence. The proliferation of youth-oriented programs at the schools gave them a way to escape their past. As crime came down, new businesses started opening, including franchises like McDonald’s, and they offered low-level entry jobs that drew youth into work. As Chicago became more of a hub for the regional distribution of goods, more jobs were created as wholesale warehouses and refrigeration centers opened in Pilsen, drawn by the still-low real estate prices and falling crime.

With the area more livable, the Resurrection Project turned to keeping the poor, some of who have very few assets and very little buffer against a sudden loss of job or illness, in their rented homes. This would stabilize the community, but it gets harder as the community strengthens because rents are increasing and buying is becoming costlier. The Resurrection Project tries to increase access to credit locally, so that people have options. Its volunteers work with community members to improve their financial understanding, to get them to build and improve their credit histories by, for example, paying their utility bills regularly and on time.

Large banks, of which a growing number have now set up in the community, are not well equipped to understand community practices. This hampers their lending. In Pilsen, a working woman’s mother will often cook for her and babysit her children, so the worker’s salary goes a much longer way because she does not pay for these services. Similarly, family members may lend each other money, making it possible for someone to keep up loan payments even if their income is volatile. Typically, such practices are hard for a loan officer from a large bank to substantiate or document, which is why he has to go primarily on the explicit record of income.8 Community-based financial institutions, where decisions are made locally based on their better understanding of the community, know the worker is more creditworthy than her salary slip might suggest. Being free from the tyranny of requiring hard documentation, they are more willing to lend locally than large banks.

Recognizing the importance of local institutions, in 2013 the Resurrection Project helped rescue a failing community bank, Second Federal. At that time, 29 percent of the bank’s mortgages were delinquent, and many local borrowers would have faced eviction if the bank had been closed or sold outside the community. Vacancies would have depressed house prices and brought back crime. Second Federal’s delinquencies are now down to 4 percent of its mortgage portfolio, because it worked with its borrowers and nursed the loans back to health. People continue to use its branch as a community center, meeting there to chat with neighbors, or bringing their mail to have it translated by tellers.

The Resurrection Project has itself built affordable housing that it rents to needy families, nudging them to move out when they can afford market rents. One of its developments, Casa Queretaro, looks sleek and welcoming, seeming more luxury housing than “affordable”—in management’s view, there is no reason why so much affordable housing should look run down.

There is much more to community revival, but the picture should be clear. Pilsen is by no means a rich or prosperous community but it now has hope. It has built on its Mexican connections—it has a National Museum of Mexican Art—though it is proudly American. Cinco de Mayo, a Mexican festival, is celebrated with great gusto, but over two hundred fifty thousand people join the Fourth of July parade in Pilsen. Raul Raymundo’s aim is to welcome people of every ethnicity into Pilsen while building on the core stability of the existing community. As he tells people when they buy a house, “You are not buying a piece of property, you are buying a piece of the community.”

final preliminaries

Who am I and why do I write this book? I am a professor at the University of Chicago, and I have spent time as the Chief Economist and head of Research at the International Monetary Fund, where we gave advice to a variety of industrial and developing countries. I also was the Governor of India’s central bank, where we undertook reforms to improve India’s financial system. I have experience working in both the international financial system and in an emerging market. In my adult life, I have never been more concerned about the direction our leaders are taking us than I am today.

In my book Fault Lines: How Hidden Fractures Still Threaten the World Economy, published in 2010, I worried about the consequences of rising inequality, arguing that easy housing credit before the Global Financial Crisis was, in part, a way for politicians to deflect people’s attention from their stagnant paychecks. I was concerned that instead of drawing the right lesson from the crisis—that we need to fix the deep fault lines in developed societies and the global order—we would search for scapegoats. I wrote:

“The first victims of a political search for scapegoats are those who are visible, easily demonized, but powerless to defend themselves. The illegal immigrant or the foreign worker do not vote, but they are essential to the economy—the former because they often do jobs no one else will touch in normal times, and the latter because they are the source of the cheap imports that have raised the standard of living for all, but especially those with low incomes. There has to be a better way . . .”9

The search for scapegoats is well and truly on. I write this book because I see an increasingly polarized world that risks turning its back on seventy years of widespread peace and prosperity. It threatens to forget what has worked, even while ignoring what needs to change. The populist nationalists and the radical Left understand the need for reform, but they resort to the politics of anger and envy. The mainstream establishment parties do not even admit to the need for change. There is much to do, and the challenges are mounting—population aging and climate change need to be addressed without delay. We must start now to bring the state, markets, and the community into a much better balance within our countries, so that we can come together as confident healthy nations to address looming global problems.

The rest of this book is as follows. I start by describing the third pillar, the community. To some, the community stands for warmth and support. To others, it represents narrow-mindedness and traditionalism. Both descriptions can be true, sometimes simultaneously, and we will see why. The challenge for the modern community is to get more of the good while minimizing the bad. We will see how this can be obtained through the balancing influence of the other two pillars—the state and markets. To continue our exploration, we must understand how these pillars emerged historically. In Part I, I trace how the state and markets in today’s advanced countries grew out of the feudal community, taking over some of its activities. I explain how a vibrant market helped create independent sources of power that limited the arbitrary powers of the state. As the state became constitutionally limited, markets got the upper hand, sometimes to the detriment of communities. The extension of suffrage reempowered communities and they used it to press the state to impose regulatory limits on the market. People also demanded reliable social protections that would buffer them against market volatility. All these influences came together in the liberal market democracies, which emerged across the developed world in the early twentieth century. However, market downturns, especially following technological revolutions, were, and are, disruptive. The Great Depression, followed by the Second World War, seemed to sound the death knell of liberal market democracies in much of the world, and the ascent of the state. The balance was seriously disturbed.

In Part II, I describe how the United States shaped the postwar liberal order, and how both the state and markets grew once again to re-create a new balance. Democracy’s roots became stronger. The thirty years of strong postwar growth, however, were followed by years of relative stagnation as developed countries struggled for new ways of reviving growth. In response, the Anglo-American countries empowered the markets at the expense of the state, while continental European reforms favored the superstate and the integrated market. Both sets of reforms came at the expense of the community. I discuss how these different choices left countries differently positioned for the ICT revolution, the subsequent Global Financial Crisis, the backlash against the global order, and the rise of populism.

I turn to possible solutions in Part III. To strengthen the chances that society will stay liberal and democratic, we need profound changes that rebalance the three pillars in the face of technological change. We need more localism to empower the community while drawing on the state and markets to make society more inclusive.

Finally, some caveats. I intend this book to be comprehensive, but not exhaustive. Therefore, I illustrate the course of history with examples from prominent countries, but it would tax the reader’s patience (as well as my editor’s) if I substantiated points with the detail that specialists require. This book offers a broad thesis of its own, and draws on much academic work, but it is aimed at a wide audience. I also offer policy proposals, not as the final word but to provoke debate. We face enormous challenges, to which we need not just the right solutions but also ones that inspire us to act. It is worth recalling the words of Chicago architect Daniel Burnham, “Make no little plans; they have no magic to stir men’s blood and probably themselves will not be realized.”10 I hope this book stirs you to big plans.