Читать книгу The Activist's Handbook - Randy Shaw - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

Don’t Respond, Strategize

In a previous era, social change activists were guided by the immortal words of Mary “Mother” Jones: “Don’t mourn, organize.” These words, spoken following the murder of a union activist, emphasized the value of proactive responses to critical events. Although American activists today face less risk of being killed, they still must heed Mother Jones’s command. A political environment hostile to progressive change has succeeded in putting many social change activists on the defensive, and the need for proactive planning—what I like to call tactical activism—has never been clearer.

Unfortunately, proactive strategies and tactics for change all too frequently are sacrificed in the rush to respond to the opposition’s agenda. Of course, activists must organize and rally to defeat specific attacks directed against their constituencies; if a proposed freeway will level your neighborhood, preventing the freeway’s construction is the sole possible strategy. I am speaking, however, of the far more common scenario where the opposition pushes a particular proposal or project that will impact a constituency without threatening its existence. In these cases, it is critical that a defensive response also lays the groundwork for achieving the long-term goal.

The best way to understand tactical activism is to view it in practice. The Tenderloin neighborhood of San Francisco, where I have worked since 1980, is a virtual laboratory demonstrating both the benefits of tactical activism and the consequences of its absence. The Tenderloin won historic victories using proactive strategies in response to luxury tourist developments threatening its future, but had less success in responding defensively to crime. This chapter also discusses how the Occupy movement used proactive activism to reshape the national debate about inequality, and how activists played into their opponents hands by allowing homelessness to be reframed from a socially caused housing problem to a problem of individual behavior.

THE TENDERLOIN: TACTICAL ACTIVISM AT WORK

The Tenderloin in San Francisco lies between City Hall and the posh downtown shopping and theater district of Union Square. Once a thriving area of bars, restaurants, and theaters, the Tenderloin gave birth to the city’s gay and lesbian movement and was long home to thousands of merchant seamen and blue-collar workers living in the neighborhood’s more than one hundred residential hotels. When I arrived in the Tenderloin in 1980, it was often described as San Francisco’s “seedy” district—a not entirely inaccurate depiction. For at least the prior decade, the Tenderloin had more than its share of prostitution, public drunkenness, and crime. It was notorious for its abundance of peep shows, porno movie houses, and nude-dancing venues; the high profile of these businesses and their flashing lights and lurid signs fostered the neighborhood’s unsavory reputation.

The Tenderloin’s location in the heart of a major U.S. city distinguishes it from other economically depressed neighborhoods. Many people who spend their entire lives in Los Angeles or New York City never have cause to go to Skid Row or the South Bronx; Bay Area residents can easily avoid the high-crime area of East Oakland. However, most San Franciscans are likely to pass through the Tenderloin at some point—to visit one of the city’s major theaters or the Asian Art Museum, to see a friend staying at the Hilton Hotel or Hotel Monaco (both located in the Tenderloin), to conduct business at nearby City Hall, or to reach any number of other destinations. San Franciscans have firsthand experience with the Tenderloin that is highly unusual for low-income neighborhoods.

The thirty-five blocks at the core of the neighborhood constitute one of the most heterogeneous areas in the United States, if not the world. The Tenderloin’s 20,000 residents include large numbers of senior citizens, who are primarily Caucasian; immigrant families from Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos; a significant but less visible number of Latino families; perhaps San Francisco’s largest concentration of single African American men, and a smaller number of African American families; one of the largest populations of gays outside the city’s Castro district; and a significant number of East Indian families, who own or manage most of the neighborhood’s residential hotels. The Tenderloin’s broad ethnic, religious, and lifestyle diversity has held steady as the rest of San Francisco has become more racially segregated over the past decades.

With government offices and cultural facilities in the Civic Center to the west, the city’s leading transit hub on Market Street to the south, the American Conservatory and Curran Theaters to the north, and Union Square (one of the most profitable shopping districts in the United States) to the east, in the late 1970s the neighborhood’s economic revival was said to be just around the corner. This widespread belief in the imminent gentrification of the Tenderloin profoundly shaped its future. During that time, Tenderloin land values rose to levels more appropriate to the posh lower Nob Hill area than to a community beset with unemployment, crime, and a decrepit housing stock. Real estate speculators began buying up Tenderloin apartment buildings, and developers began unveiling plans for new luxury tourist hotels and condominium towers.

Further impetus for the belief in imminent gentrification came from the arrival in the late 1970s of thousands of refugees, first from Vietnam, then from Cambodia and Laos. The Tenderloin was chosen for refugee resettlement because its high apartment-vacancy rate made it the only area of the city that could accommodate thousands of newly arrived families. The refugees’ arrival fostered optimism about the Tenderloin’s future in three significant ways. First, the refugees filled long-standing apartment vacancies and thus raised neighborhood property values and brought instant profits to Tenderloin landowners. Second, many in the first wave of refugees left Vietnam with capital, which they proceeded to invest in new, Asian-oriented businesses in the Tenderloin. These businesses, primarily street-level markets and restaurants, gave the neighborhood a new sense of vitality and drove up the value of ground-floor commercial space.

Third, and perhaps most significant, those eager for gentrification expected Southeast Asian immigrant families to replace the Tenderloin’s long-standing population of seniors, merchant seamen, other low-income working people, and disabled persons. The families, it was thought, would transform the neighborhood into a Southeast Asian version of San Francisco’s popular Chinatown.

My introduction to the Tenderloin came through Hastings Law School, another significant player in the Tenderloin development scene. In 1979, when I was twenty-three, I enrolled as a student at Hastings, a public institution connected to the University of California. During the 1970s, Hastings had expanded its “campus” by vacating tenants from some adjacent residential hotels. Until 2006, its relationship to the lowincome residents of the Tenderloin was based on the perspective of territorial imperative, one shared by urban academic institutions such as Columbia and the University of Chicago. Hastings was aptly described during its expansion phase as the law school that “ate the Tenderloin.”

I became involved in trying to help Tenderloin residents soon after starting at Hastings. My personal concern was tenants’ rights, an interest developed when I lived in Berkeley while attending the University of California. On February 1, 1980, I joined fellow law students in opening a center to help Tenderloin tenants prevent evictions and assert their rights. Our center, called the Tenderloin Housing Clinic, started with a budget of $50, and our all-volunteer staff was housed in a small room at Glide Memorial Church, in the heart of the neighborhood.

When we opened the Clinic, the Tenderloin did not appear to be on the verge of an economic boom. Some thriving Asian markets had opened, and nonprofit housing corporations had begun to acquire and rehabilitate some buildings, but the dominant impression was of an economically depressed community whose residents desperately needed various forms of help. The inhabitants of the Tenderloin, unaware of the agenda of those predicting upscale development, would have laughed at anyone proclaiming that neighborhood prosperity was just around the corner. How quickly everyone’s perspective would change in the months ahead!

Almost immediately, I found myself plunged into what remains my best experience of how tactical activism can transform a defensive battle into a springboard toward accomplishing a significant goal. In June 1980 I was invited to a meeting at the offices of the North of Market Planning Coalition (NOMPC). NOMPC initially comprised agencies serving the Tenderloin population. In 1979, however, it obtained enough staff through the federal VISTA program (the domestic incarnation of the Peace Corps) to transform itself into a true citizen-based organization. The VISTA organizers were like me: recent college graduates from middle-class backgrounds excited about trying to help Tenderloin residents. The convener of the June 1980 meeting, Richard Livingston, had secured the VISTA money for NOMPC with the vision of getting neighborhood residents involved in planning the community’s future.1

Livingston revealed that three of the most powerful hospitality chains in the world—Holiday Inn, Ramada, and Hilton—had launched plans to build three luxury tourist hotels in the neighborhood. The three towers would reach thirty-two, twenty-seven, and twenty-five stories, respectively, containing more than 2,200 new tourist rooms. The news outraged us; the encroachment of these big-money corporations would surely drive up property values, leading to further development and gentrification and, ultimately, the obliteration of the neighborhood. Fighting construction of the hotels, however, presented mammoth difficulties. None of the hotels would directly displace current residents, so the projects could not be attacked on this ground, and zoning laws allowed for the development of the proposed luxury high-rise hotels, which removed a potential legal barrier.

The situation seemed hopeless. The Tenderloin’s residents were entirely unorganized, NOMPC’s newly hired VISTA organizers were energetic but inexperienced, and our opponents were multinational hotel corporations in a city where the tourist industry set all the rules. How could we succeed in preserving and enhancing the Tenderloin as an affordable residential community for the elderly, poor, and disabled in the face of this three-pronged attack? The answer lay in tactical activism.

Prior to the threat of the hotels, NOMPC’s central goal for the Tenderloin was to win its acceptance as an actual neighborhood worthy of assistance from the city. The lack of participation by Tenderloin residents and agency staff in the city’s political life had led to a consensus, accepted even by progressive activists, that a viable neighborhood entity north of Market Street did not exist. The hotel fight gave NOMPC the opportunity to educate the rest of the city about the state of affairs in the Tenderloin. As the Coalition organized residents to fight the hotels, the overall strategy became clear: first, to establish that the Tenderloin was a residential neighborhood and, second, to insist that, as such, it was entitled to the same zoning protections for its residents as other San Francisco neighborhoods. If NOMPC could force City Hall and the hotel developers to accept the first premise, the second premise—and NOMPC’s strategic goal—would follow.2

The attempt to rezone the neighborhood in response to the hotel development threat was certainly not inevitable; it was the result of carefully considered tactical activism. Instead of using the hotel fight as a springboard for change, the organization could have made the usual antidevelopment protests, then sat back and awaited the next development project in the neighborhood. The organizational identity could have been that of a fighter of David-and-Goliath battles pitting powerless citizens against greedy developers. Livingston, NOMPC organizer Sara Colm, and other Tenderloin organizers understood, however, that development projects are rarely stopped and are at best mitigated. This is particularly true where development opponents are primarily low-income people and where the local political leadership—as is true for most cities, large and small—is beholden to developers and real estate interests.

The organizers foresaw that a succession of fights against specific development projects would destroy the residential character of the neighborhood they wished to strengthen. A rezoning of the community, in contrast, would prevent all future development projects without directly attacking the financial interests of any particular developer. A proactive battle for neighborhood rezoning was thus both the most effective and the most politically practical strategy. “No hotels” was not a solution to the neighborhood’s problem—rezoning was.

In concert with the local chapter of the Gray Panthers, many of whose senior activist members lived in the Tenderloin, NOMPC unified residents by forming the Luxury Hotel Task Force. The Task Force became the vehicle of resident opposition to the hotels, but it had a greater and more strategic importance as a visible manifestation that the Tenderloin was a true residential neighborhood. Although most Task Force members had lived in the Tenderloin for years, they were invisible to the city’s political forces. Suddenly, hotel developers and their attorneys, elected Officials, and San Francisco Planning Department staff were confronted with a group of residents from a neighborhood whose existence they had never before recognized. The Tenderloin residents’ unified expression of concern over the hotels’ possible impact on their lives permanently changed the political calculus of the neighborhood. Once the developers’ representatives and city Officials encountered the Task Force, NOMPC’s strategic goal of establishing the Tenderloin as a recognizable residential neighborhood was achieved.

The battle against the hotels was short and intense. After learning of the proposal in June, we held two large community meetings in July. More than 250 people attended the meetings, a turnout unprecedented in Tenderloin history. The formal approval process for the hotels began with a Planning Commission hearing on November 6, at which more than 100 residents testified against the project. Final commission approval came on January 29, 1981, in a hearing that began in the afternoon and ended early the next morning.

The projects clearly had been placed on the fast track for approval; the city was in the midst of “Manhattanization,” a building boom during which virtually no high-rise development project was disapproved. This made the accomplishments of the Luxury Hotel Task Force that much more astounding. As a result of residents’ complaints that the hotels would have a “significant adverse environmental impact” on rents, air quality, and traffic in the Tenderloin, the commission imposed several conditions to mitigate these effects. The hotels had to contribute an amount equal to fifty cents per hotel room for twenty years for low-cost housing development (about $320,000 per hotel per year). Additionally, each hotel had to pay $200,000 for community service projects, sponsor a $4 million grant for the acquisition and renovation of four low-cost residential hotels (474 units total), and act in good faith to give priority in employment to Tenderloin residents.

Such “mitigation measures” are now commonplace conditions of development approval in U.S. cities, but they were unprecedented in January 1981. In the view of local media and business leaders, that a group of elderly, disabled, and low-income residents had won historic concessions from three major international hotel chains in a prodevelopment political climate was an ominous precedent. San Francisco Chronicle columnist Abe Mellinkoff weighed in strongly against “the squeeze” in two consecutive columns following the Planning Commission vote. Referring to the mitigations as a “shakedown” undertaken by “bank robbers,” Mellinkoff urged the business establishment to publicly protest this “rip-off of fellow capitalists.” As Mellinkoff saw it, Luxury Hotel Task Force members were “crusaders” and “eager soldiers” whom City Hall had allowed to prevail in “a war against corporations.” Clearly, NOMPC’s strategy had worked. The hotel fight had made the Tenderloin a neighborhood to be reckoned with.3

The decision to use this defensive battle to achieve a critical goal resulted entirely from continual discussions of strategy and tactics among the thirty to forty residents who regularly attended Luxury Hotel Task Force meetings. A good example of the group’s extensive tactical debates arose when the Hilton Hotel offered to provide lunch at a meeting to discuss its project. Gray Panther organizer Jim Shoch, whose tactical insights were critical to the Task Force’s success, made sure that every facet of the Hilton offer was analyzed for its implications. Some Task Force members felt that lunch should be refused so the Hilton couldn’t “buy us off.” The majority wanted to take advantage of a high-quality lunch, recognizing it as a vast improvement over their normal fare. Ultimately, the group went to the lunch but gave no quarter to the Hilton in the meeting that followed.

These time-consuming and often frustrating internal discussions enabled residents to understand that they did not have to accomplish the impossible (i.e., prevent approval of the towers) to score a victory. Without this understanding, the city’s ultimate approval of the hotels could have been psychologically and emotionally devastating. Instead, the Planning Commission’s approval did not diminish residents’ feelings that they had achieved a great triumph in their own lives and in the neighborhood’s history.

With city Officials having recognized the Tenderloin as a viable neighborhood, the Task Force turned to the second half of NOMPC’s agenda: establishing the Tenderloin’s right to residential rezoning. In 1981, San Francisco residents could initiate the rezoning process by circulating petitions in the neighborhood in question. NOMPC began its rezoning campaign immediately after the city’s approval of the luxury hotels. The rezoning proposal affected sixty-seven square blocks overall, with the strictest downzoning proposed for the thirty-five-square-block heart of the Tenderloin.

In this central area, the new zoning prohibited new tourist hotels, prevented commercial use above the second floor, and imposed eight- to thirteen-story height restrictions. The strategy succeeded largely because of its timing: on the heels of the Planning Commission’s approval of the hotel towers, even the pro-growth local political leadership felt the neighborhood should not be required to accept additional commercial high-rise development. But the city’s sense of obligation to residents of a low-income community might quickly evaporate in the face of a new high-rise development proposal; quick action was necessary to prevent new projects from emerging as threats.

The wisdom of the strategy was confirmed in 1983, prior to the city’s approval of the rezoning. A one-million-square-foot development that included hotels, restaurants, and shops was proposed for the heart of the Tenderloin. The project, “Union Square West,” effectively would have destroyed the affordable residential character of a major portion of the neighborhood. Clearly, Union Square West conflicted with the fundamental premise of the rezoning proposal; the project included three towers ranging between seventeen and thirty stories, a 450-room tourist hotel, and 370 condominium units. Would the pro-growth Planning Commission turn its back on the neighborhood and support the project? In the absence of the rezoning campaign, and despite the “obligation” incurred to the community after approval of the luxury hotels, San Francisco’s Planning Commission undoubtedly would have authorized the project. The tactical activism of NOMPC, however, preempted the mammoth proposal. When Union Square West went for approval on June 9, 1983, the ardently pro-growth Planning Commission chairman strongly chastised the developer. The rezoning process had gone too far for the city to change its mind. A project that would otherwise have been approved was soundly defeated.

The Tenderloin rezoning proposal was signed into law on March 28, 1985. Its passage culminated nearly five years of strategic planning that had involved hundreds of low-income people in ongoing tactical discussions. The rezoning enabled the Tenderloin to avoid the gentrification that occurred in virtually every other central-city neighborhood across the nation in the following three decades. Today, thirty-one blocks of the still-low-income neighborhood constitute the nationally recognized Uptown Tenderloin Historic District, listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The North of Market Planning Coalition’s transformation of a major threat into a springboard for achieving longsought goals stands as a shining example of what can be accomplished through tactical activism.

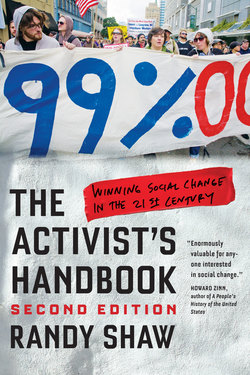

THE OCCUPY MOVEMENT: WE ARE THE 99 PERCENT

Tactical activism is also vital in national campaigns. Activists seeking to implement a proactive agenda must overcome corporate and wealthy interests that not only spend billions to frame issues in their preferred terms but also have strong media allies to further their goals. That’s why Occupy Wall Street’s success in the fall of 2011 is so impressive. Occupy activists reframed a complex series of economic and social forces into a bumper sticker paradigm: the 1 percent versus the 99 percent. And after creating a new way for understanding inequality, Occupy trusted its instincts and avoided arcane policy debates and pressure to submit a list of “demands.” While some Occupy activists later became reactive, and the movement’s growth did not meet the expectations of its most enthusiastic backers, the Occupy movement reshaped the nation’s political dialogue in its first two months alone. Occupy also shows the grassroots energy that can be tapped when activists aspire to transcend conventional wisdom about what is politically possible.

Occupy Emerges

On July 13, 2011, the anti-capitalist Vancouver-based online publication Adbusters called for “20,000 people” to “flood into lower Manhattan, set up tents, kitchens, peaceful barricades and occupy Wall Street for a few months.” The protest was set to begin on September 17. While gathering 20,000 protesters in New York City is not difficult, the plan was for people to “occupy” a park for not just a night or a weekend, but for “a few months.” Adbusters had no idea how many would respond to its call. Some activists were mobilizing. A group known as US Day of Rage was organizing actions that day in New York City, Austin, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Seattle, and the protests were promoted on websites and tweets put out by the Internet hacktivist group Anonymous; and local activists associated with the newly formed New York General Assembly were committed to the plan. But labor unions, churches, and other large institutions whose outreach is often necessary to generate major turnouts were not involved. Nor was there an Official website, commonly used to mobilize mass events.4

On September 14, Nathan Schneider wrote on Adbusters’ website: “Not only will this weekend be a test of Americans’ readiness to resist, but of whether an idea lobbed into the internet by Adbusters, then grabbed by artists, students, Twitter hashtags, and a shadowy network of hackers (and hacker wannabes), can really turn into a ‘flood,’ a show of meaningful political force, a new way forward.”5 Many would have questioned whether the Adbusters network and its anarchist allies could create a viable “test of Americans’ readiness to resist,” given their lack of connection to mainstream progressive organizations.

Nevertheless, as many progressives despaired over President Obama’s failure and/or inability to implement his 2008 campaign vision, Adbusters and its initial allies saw an opportunity to tap grassroots discontent that nearly everyone else missed. Occupy’s call revived demands to address Wall Street abuses, rising income and economic inequality, and the inability of the U.S. political system to address either. Occupy also provided activists with an organizational vehicle to pursue this agenda. By offering both a vision and a vehicle, the Occupy movement became a case study in the power of proactive grassroots activism.

Redefining the National Agenda

Occupy’s very first protest showed that when activists take the initiative, it can cause strategically wrong responses on the part of government or other power centers that help expand the movement. The New York City Police Department made two early decisions that fueled Occupy’s growth.

First, the September 17 occupation was originally planned for 1 Chase Plaza, the site of the “Charging Bull” sculpture symbolizing nearby Wall Street. But this was a public space. Police fenced it off after learning of the planned takeover. The occupation then shifted to Zuccotti Park, which was private property. This meant that police could not force protesters to leave absent the property owner’s request. Zuccotti was a far better site for pitching tents, setting up tables, holding meetings, and attracting people to Occupy Wall Street. Not recognizing that the city had given a great gift to Occupiers by shifting the protest to a private site, New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg told a September 17 press conference that “people have a right to protest, and if they want to protest, we’ll be happy to make sure they have locations to do it.”6

The September 17 protests included about one thousand people, only 5 percent of the number that organizers projected. It received little media attention. Follow-up protests were also ignored. Keith Olbermann observed on his MSNBC show Countdown on September 21, 2011, that “after five straight days of sit-ins, marches, and shouting, and some arrests, actual North American newspaper coverage of this—even by those who have thought it farce or failure—has been limited to one blurb in a free newspaper in Manhattan and a column in the Toronto Star.” He noted that, in contrast, “a tea party protest in front of Wall Street about [Federal Reserve chief] Ben Bernanke putting stimulus funds into it, it’s the lead story on every network newscast.”7

The lack of media coverage obscured the fact that activists were still learning about the occupation. As more visited Zuccotti Park and came away impressed, Occupy’s message expanded. Many got their first opportunity to join an Occupy protest on Saturday, October 1. This rainy day became a significant turning point for the Occupy movement. Once again, a proactive move by Occupy triggered a counterproductive police response that helped build the campaign. In this case, when Occupy protesters began walking across the Brooklyn Bridge—a very common New York City activist tactic—more than seven hundred were arrested. The protesters were apprehended despite having engaged in no violence, vandalism, or civil disobedience. Nor were they trying to block traffic. In fact, Occupy had tried to avoid conflicts with police.

The huge number of arrests made headlines. It also put the Occupy movement on the national map. Media coverage of the mass arrests necessarily reported Occupy’s arguments about inequality, boosting plans already in the works to expand local Occupy actions nationwide. Occupy now attracted support from labor unions and other more mainstream progressive groups. The symbolism of the arrests could not have been more effective: the same police force that protected Wall Street was used to arrest Occupy protesters, with many assuming that the NYPD had acted at the behest of the 1 percent. To top it off, the media sided with the marchers’ version of events. As the New York Times put it, “Many protesters said they believed the police had tricked them, allowing them onto the bridge, and even escorting them partway across, only to trap them in orange netting after hundreds had entered.”8

The Brooklyn Bridge arrests turned Occupy into a national story. Reporters unable pre-Occupy to convince editors to cover rising economic inequality were now given space to address the issue. Republican presidential front-runner Mitt Romney then added fuel to the growing media fire by criticizing the Occupy protests as “class warfare”; this comment effectively turned income inequality into a partisan issue. When thousands took to the streets in New York City to express solidarity with Occupy, President Obama said he “understood” the protesters’ concern: “It expresses the frustrations that the American people feel that we had the biggest financial crisis since the Great Depression, huge collateral damage all throughout the country, all across Main Street. And yet you’re still seeing some of the same folks who acted irresponsibly trying to fight efforts to crack down on abusive practices that got us into this problem in the first place.” For many who were disappointed with Obama’s aligning with Wall Street after taking office, such words meant that the president clearly saw Occupy’s agenda as reshaping the national debate.9

Proactively Framing the Movement

Only two weeks after occupying Zuccotti Park on September 17, the Occupy movement was a national phenomenon. But activists took nothing for granted, including their ability to continue camping in the private park. Mayor Bloomberg’s assurance that the city would provide Occupiers with locations to protest meant that a quick eviction would appear hypocritical; nonetheless, activists took a number of proactive steps to protect the occupation by framing it as a political gathering rather than a squatters’ encampment.

To this end Occupy maintained a library of progressive books, many donated by publishers and authors eager to connect their works with the emerging movement. Activists also launched the Occupied Wall Street Journal newspaper, whose 50,000 press run was funded by the crowd-funding site Kickstarter. Adding to the sense that this was a political movement and not simply a homeless tent city were publicly posted agendas for each day’s activities, including training sessions, educational events, and the General Assembly meetings that became widely identified with the movement.

Since city restrictions banned electrical amplification at Zuccotti Park, speakers relied on a call-and-response system known as human microphones. Speakers’ words were repeated by the entire assembly, including each meeting’s starting call for a “mic check.” Richard Kim described a meeting on October 6, 2011: “The overall effect can be hypnotic, comic or exhilarating—often all at once. As with every media technology, to some degree the medium is the message. It’s hard to be a downer over the human mic when your words are enthusiastically shouted back at you by hundreds of fellow occupiers, so speakers are usually pretty upbeat (or at least sound that way). Likewise, the human mic is not so good for getting across complex points about, say, how the Federal Reserve’s practice of quantitative easing is inadequate to address the current shortage of global aggregate demand . . . so speakers tend to express their ideas in straightforward narrative or moral language.”10

The call-and-response approach replicated a vision of grassroots democracy harkening back to the New England town meeting. This turned the General Assembly at Zuccotti Park into a model for the type of democratic system in which the people rather than big-money interests rule—a model to which Occupiers wanted the nation to return.

New York City activists had spent months preparing for September 17 and its aftermath. The structure, design, and agenda of the Zuccotti Park occupation were no accident. When Mayor Bloomberg announced that authorities would “clean the park” and evict Occupy on October 14, all believed that the mayor was calling the shots on behalf of Brookfield Properties, the private owner, and public sympathy toward the Zuccotti campers was strong. In fact, it was so strong that Bloomberg withdrew the planned eviction rather than face thousands of sympathizers planning to descend on Zuccotti Park on the morning of the 14th to save Occupy. The response to the possible shutdown of the encampment showed that Occupy had created a remarkable sense of community built along class lines. From activists wearing buttons to signs displayed in retail businesses, a new sense of unity emerged around Occupy’s slogan, “We Are the 99%.”

From the October 1 Brooklyn Bridge arrests to the October 14 planned eviction, media coverage of the movement increased exponentially. Although activists had long decried the widening gap between the rich and everyone else, Occupy’s 1 percent–versus–99 percent rallying cry publicized economic inequality in a way not seen since the New Deal. It was as if a big curtain titled “American Dream” had been pulled away, exposing a system rigged for the rich against the middle class and the rest of the 99 percent. The traditional media, rarely aligned with progressive attacks on the wealthy, provided surprisingly favorable coverage in Occupy’s first weeks. Rather than profile young anarchists expressing contempt for capitalism—the standard media image for antiglobalization protests—Occupy stories focused on hardworking, down-on-their-luck Americans who simply wanted a job, a roof over their heads, or a living wage.

These positive media stories were no accident. The Occupy movement relied on hard economic facts to make its case, and maintained an intellectual integrity that swayed mainstream reporters. The media portrayed the movement as more than angry youth acting out against authority. An online survey of traffic to the OccupyWallStreet website on October 5, 2011, found that Occupiers reflected the diversity of the nation. The report “Main Stream Support for a Mainstream Movement: The 99% Movement Comes from and Looks Like the 99%” revealed a surprisingly broad consensus that Occupiers were regular folks. This sharply contrasted with the way protesters challenging corporate power are often portrayed in the United States.11

A Demand for Demands

Although Occupy was growing and creating a national debate about class and income inequality, some began questioning the movement’s alleged lack of specific demands. At one level, the idea that a movement demanding greater economic fairness and increased restrictions on Wall Street somehow lacked demands made no sense; politicians certainly knew how to address these concerns. Yet for some activists, issuing a list of specific demands to those in power was part of Organizing 101. They argued that absent demands, politicians would co-opt the movement, those in power would be under no pressure to acquiesce, and the movement would even become “a joke.”12

These critics misunderstood the Occupy project. Occupy sought to propel a political and cultural shift toward redistributing the nation’s wealth. Occupy was not akin to a neighborhood group pressuring a politician to clean up a park, or a national campaign pushing the president or Congress to stop construction of a pipeline. Occupy was also very different from previous high-profile anti-corporate campaigns against Gallo Wine, J. P. Stevens, and Nike, all of which addressed a specific set of abuses. Occupy captivated the public by offering a systemic challenge to a political and economic structure that had proved impervious to piecemeal reforms. Furthermore, the notion that Occupy’s relatively small base in October 2011 gave it authority to issue specific demands on behalf of “the 99 percent” would have mocked its own critiques of the democratic process. Rather than squander time and effort debating demands, Occupy needed to continue expanding its base.

Formalizing demands would also have been a mistake because it would have shifted Occupy’s struggle to Wall Street and its political opponents’ favored turf: Congress and banking regulators. Once Occupy became yet another Beltway lobbying force, it would have no energy left for tactics that could really shake up the system. Occupy wisely recognized that the 1 percent and Congress would not agree to any meaningful “demands.” Pursuing and then failing to achieve legislative changes would simply allow critics to quickly declare the movement’s failure.

The Movement Grows

On October 25, 2011, hundreds of police officers wearing gas masks and riot gear, firing rubber bullets, and using tear gas stormed Occupy Oakland’s base in a public plaza. The police assault left Scott Olsen, a twenty-four-year-old marine, in critical condition after a blow to his head from a tear gas canister fired by police fractured his skull and led to swelling of the brain. Footage of the police violence played on television for days. The dominant theme was that Olsen had survived two tours of duty in Iraq but was nearly killed while peacefully protesting in Oakland. Nobody defended the police actions, and even media generally sympathetic to law enforcement condemned the excessive force.

The attacks gave the Occupy movement more positive national publicity than ever before. Many activists saw the Oakland police response as evidence that Occupy’s message was unhinging the elite, who could defend their greed only through violence. The media saw Iraq War veteran Olsen, who was working in the computer industry at the time, as the type of “mainstream” supporter the Occupy movement had attracted. Olsen’s biography forced the media to acknowledge that a struggle initiated by anarchists and anti-establishment forces now extended beyond the traditional activist base.

On November 2, Occupy Oakland held a “General Strike” that brought more than 10,000 protesters marching through the city. This tremendous display of nonviolent unity was enormously empowering for many of those involved. While late-night vandalism by black-clad anarchists drew attention, the media went out of their way to distinguish this behavior from Occupy’s daytime protesters. Many participants saw the General Strike as just the beginning, creating momentum for a broader movement for change.

But the mass strike would instead prove Occupy Oakland’s high point. Occupy Oakland did no systematic recruitment on November 2, and those coordinating the General Strike failed to get email, phone, or other contact information helpful for enlisting activists for future protests. Nor was a follow-up event announced that would have left protesters feeling that the General Strike was not a one-shot deal but was part of a larger strategy. Instead of affirmatively mobilizing hundreds of new activists to be centrally involved in a broader movement, Occupy coordinators apparently assumed that they could use the same turnout tactics in future actions that they had used for the General Strike. But many labor unions and other groups that had mobilized for the strike could not devote similar resources toward building future large Occupy turnouts. Occupy Oakland missed a great opportunity in not building upon the General Strike, and as a result, thousands departed the spectacular one-day protest without ever returning to the movement.

Going Off Message

The October 25 police attacks and November 2 General Strike gave Occupy Oakland a high national profile. But the group soon shifted its focus from “the 1 percent” to challenging Oakland mayor Jean Quan and insisting on its right to continue camping in the public plaza that had been the site of the attacks. Occupy Oakland never recovered from this shift from targeting income inequality to challenging misconduct by Oakland public Officials. To be sure, Oakland activists had long battled police misconduct, and many Occupiers saw reclaiming public spaces (or “the commons”) as a central movement goal. But neither Quan nor any other urban mayor had the power to rectify staggering national income inequality, and targeting wayward Oakland Officials got the once-promising local Occupy movement off track.

Following the police attacks, Occupy Oakland continued to generate publicity. But now it was about confrontations with Oakland’s mayor and police chief, and fights over the right to camp in a public plaza. Occupy Oakland’s activities soon had little direct connection to Wall Street or the financial sector. There were major confrontations with police over occupying a vacant city building and blocking the Oakland port. Meanwhile, Occupy’s image as representing a truly democratic, grassroots decision-making process came under scrutiny. A process that required people to attend meetings deep into the night did not work for those with family responsibilities or other work commitments. In fact, it skewed decision making to a small segment of “the 99 percent” that had time to attend hours of outdoor evening meetings on work nights. A process claiming to be truly democratic effectively excluded many of those who might have become heavily involved in the movement following the General Strike.

Occupy Oakland was only one branch of a national movement, but its ongoing confrontations with police greatly raised its national profile. When a small number of protesters associated with Occupy Oakland engaged in vandalism against downtown businesses, defenders of this tactic correctly argued that it was sanctioned by Occupy. By refusing to reject violence, Occupy Oakland marginalized itself. In debating between violent and nonviolent resistance, the movement showed how far it had strayed from the 99 percent it claimed to represent.

When Oakland Officials cleared Occupy Oakland’s encampment and arrested dozens on the morning of November 14, one activist told the media, “I don’t see how they’re going to disperse us. There are thousands of people who are going to come back.” But thousands did not come back. Occupy Oakland’s focus on police misconduct, occupying public buildings, public camping, and vandalizing property had alienated it from “the 99 percent.” The thousands who had joined the November 2 Oakland General Strike wanted to target Wall Street and “the 1 percent,” not Mayor Quan. Many would have stayed involved had Occupy Oakland not strayed from its original course.13

Police were also clearing out Occupy encampments in other cities. Many longtime supporters publicly questioned the Occupy movement’s direction, and a poll taken November 11–13, 2011, by the progressive organization Public Policy Polling appeared to confirm these doubts. The poll found that more respondents opposed (45%) than supported (33%) “the goals of the Occupy Wall Street movement.” A month earlier, the same poll had found voters equally split about Occupy. Yet more important than these numbers was the overwhelming support among respondents to the November 2011 poll for raising taxes on those earning over $150,000 a year, and their strong backing for other measures addressing income inequality. Pollster Tom Jensen noted, “What the downturn in Occupy Wall Street’s image suggests is that voters are seeing the movement as more about the ‘Occupy’ than the ‘Wall Street.’ The controversy over the protests is starting to drown out the actual message.”14

Occupy’s preoccupation with preserving its public encampments reflected its shift from a proactive to a defensive approach. Originally, the “occupying” of Zuccotti Park that launched the movement had created powerful visual imagery. Similar encampments in other cities created visibility and facilitated recruitment. But once local Occupy chapters were established, there was no reason to divert the focus from Wall Street abuses and income inequality to battling with local Officials over the right to camp. These struggles muddied the movement’s goals. Many Occupiers wanted to sleep in tents in public spaces because they lacked a place to live. But once the public saw Occupy camps as homeless encampments rather than as vehicles for economic justice, support fell. That “the 99 percent” did not support camping in public parks or plazas meant that Occupy had adopted a political position at odds with much of its purported base.

Prioritizing public encampments also caused other problems. First, it relegated those unable to live outdoors in tents to reduced roles in the movement. Second, it turned Occupy from being broadly inclusive into a group led by a small, unrepresentative fraction of “the 99 percent.” Third, it raised questions about Occupy’s moral authority to seize public plazas funded by taxpayer dollars for a sustained period, denying access to those among “the 99 percent” who wanted to use the space. No democratic process supported Occupy’s ongoing seizure of public spaces, raising questions about its legitimacy that could have been avoided had private property been occupied instead.

The battles over public camping made even less sense considering that the arrival of winter would make Occupy’s use of outdoor space as headquarters infeasible. Kalle Lasn, the founder of Adbusters, acknowledged this fact on November 14 when he wrote, “Now that winter is approaching, I can see this first wild, messy, crazy occupation phase kind of slowly winding down and the second phase will begin. Some people will continue to sleep in the snow and inspire all of us, but in the meantime many of us will go home and we will resurface next spring.” Lasn suggested that December 17, the three-month anniversary of the Occupy movement, was a good time to begin planning a spring renewal: “We use the winter to brainstorm, network, build momentum so that we may emerge rejuvenated with fresh tactics, philosophies, and a myriad projects ready to rumble next Spring.” Displaying his continued confidence in the movement’s future, Lasn added, “Permit me to be grandiose for a moment, but I can feel it—I can feel this movement is the beginning of a deep transformation of capitalism. It’s a game changer.”15

Lasn’s idea of declaring victory and regrouping for future struggles showed a strategic savvy that many Occupy activists by that time appeared to lack. When police cleared Occupy Wall Street from Zuccotti Park in an early-morning raid on November 15, they did the movement a favor; the activists’ forced ouster avoided feelings of failed personal commitment that having to leave Zuccotti due to the cold would have caused. After completely changing the way politicians, the traditional media, and much of the public perceived and talked about inequality in the United States, the Occupy movement needed time to recharge its batteries and refocus its agenda.

Regaining the Offensive

Although 2012 began with high expectations for Occupy’s resurgence, the movement faced a far more challenging political and media environment than it had when it emerged in the fall of 2011. Then, Occupy events were not competing with national or state elections for media coverage. And for activists eager to engage in social change struggles, Occupy was the leading game in town. But once 2012 began, the media began focusing on the November presidential race. Activist energies also moved to state and local primary campaigns, as well as to the June 5 recall election of Wisconsin’s Republican governor, Scott Walker. Whereas Occupy had generated 14 percent of the reporting from U.S. news organizations in mid-November 2011, by December such coverage had slid to 1 percent and was virtually nonexistent in March. More than ever, Occupy needed to recruit new activists rather than relying on mobilizing those already politically involved.16

To this end, such mainstream progressive groups as MoveOn.org, Democracy for America, and labor unions helped recruit activists for training in direct action from April 9 to 15. Thousands of current and future Occupy activists were trained in preparation for a planned “99% Spring.” (Occupy had long identified with Egypt’s 2011 Tahrir Square Uprising and the “Arab Spring” that overthrew long-standing dictatorships.) The established progressive groups sought to redirect the Occupy movement toward addressing bank abuses, foreclosures, tax breaks for the wealthy, student loan surcharges, and other core economic justice issues. The plan was for Occupy’s resurgence to take the form of spring actions targeting corporate shareholders meetings, foreclosure actions, and legislation addressing income inequality. The training sessions and events would build up to nationwide protests on May 1 in which immigrant rights and labor activists would join Occupiers in a powerful display of the power of the 99 percent.

This was clearly a proactive strategy, and direct actions targeting all of the above issues occurred throughout the spring of 2012. But the same media that had covered every facet of Occupy the preceding fall were now preoccupied with election stories. While thousands turned out for Occupy’s May 1, 2012, protests in New York City, Chicago, San Francisco, Oakland, and Seattle, the Occupy protests did not extend to smaller cities or rural areas, or outside traditional activist hotbeds. As a result, the May 1 Occupy protests got little coverage outside progressive media.

Ultimately, Occupy could not regain its past prominence in a presidential election year. As a non-electoral movement, Occupy was like a fish out of water in the national political scene of 2012. Its message did lead Democrats, from President Obama on down, to talk more about economic inequality and to strengthen opposition to tax breaks for the wealthy. But Occupy never aspired, as the Tea Party did for Republicans, to push the Democratic Party to the left by backing candidates in primaries or undertaking other electoral activism.

Measuring Occupy’s Success

Occupy continues primarily in the form of multiple groups independently challenging foreclosures, banking policies, Wall Street practices, and other issues affecting income inequality and economic fairness. Identifying these diverse actions as part of the Occupy movement put these protests in a broader and more understandable context. But a social movement is more than independent groups acting independently, and some question whether the goal of building such a movement was ever feasible or even necessary.

Occupy brought discussions of class, income inequality, and corporate greed back into the national debate. A study by Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting of leading newspapers and television news shows from the period of June–August 2011 (pre-Occupy) found the phrases “income inequality” and “corporate greed” barely mentioned; but uses of both phrases spiked dramatically after Occupy’s emergence. Similarly, Think Progress found that in the last week of July 2011, the leading cable news networks overwhelmingly focused on the national debt, while barely mentioning unemployment or the unemployed. Yet in mid-October 2011, Occupy’s emergence had made “jobs” and “Wall Street” far and away the top news media issues; the debt “crisis” barely registered. The Occupy movement clearly caused the media to shift coverage to job scarcity, Wall Street’s wealth, and the underlying economic and class issues that it had previously downplayed.17

The Pew Research Center released a poll on January 11, 2012, that appeared to confirm that Occupy-generated media coverage of income inequality had influenced public attitudes. The study found that “in just two years the perceptions of class conflict have increased significantly among members of both political parties as well as among self-described independents, conservatives, liberals and moderates. The result is that majorities of each political party and ideological point of view now agree that serious disputes exist between Americans on the top and bottom of the income ladder.” According to the study, 66 percent of the public believed that there are “very strong” or “strong” conflicts between the rich and the poor—an increase of 19 percentage points since 2009.18

Thanks to Occupy’s proactive agenda setting, millions of Americans had gained a better sense of the nation’s staggeringly unequal wealth and income distribution. And while the path toward reducing this disparity remains tortuous, Occupy activists have played an indispensable role in bringing public attention to this crisis. When Hurricane Sandy laid ruin to the Atlantic Coast and Northeast, Occupy activists created an “Occupy Sandy” campaign to mobilize and coordinate volunteer efforts by “the 99 percent.” Using social media to secure resources for those in need, Occupy Sandy showed that the inspiration that launched the Occupy movement remains strong and that its activists still aspire to make a difference in the world.

HOMELESSNESS: THE FAILURE OF DEFENSIVE ACTIVISM

In comparison to the Occupy movement’s far-reaching ambition to create a more just and equal society, the goal of ending homelessness in the United States would appear much easier to achieve. After all, the United States has sufficient wealth to provide housing for all who need it, and Congress even passed a law in 1949 pledging housing for all. But as anyone walking the nation’s streets knows, for more than two decades widespread visible homelessness has been a fact of life in the United States. Sadly, no presidential administration has called for allocating the money necessary to meaningfully reduce homelessness, even though its cause was the sharp decline in federal funding for affordable housing starting in the 1970s.

I was working in the Tenderloin when homelessness burst on to the local and national scene in 1982. I have spent three decades trying to reduce homelessness, and since 1988 my organization, the Tenderloin Housing Clinic, has created and run housing programs for homeless persons. At first, homelessness was overwhelmingly framed as a lack of affordable housing. Since the 1990s, homelessness has been associated in the public mind primarily with panhandling, public urination, “bums” sleeping on park benches, and other conduct lumped together as “problem street behavior.” This reflects a tragic shift in perception. And its impact is stark: the United States has more homeless persons today than in 1982, the federal government has never tried to end the problem, and millions of Americans are no longer surprised to see homeless people in public plazas and other areas.

How did those unwilling to provide low-income people with a roof over their heads get so much of the public on their side? After the initial wave of sympathetic media stories, conservative think tanks, activists, and politicians got to work reframing homelessness as a problem of individual behavior rather than a social problem. Unfortunately, grassroots homeless activists accepted this reframing, zealously defending people’s right to camp in public parks or panhandle on neighborhood streets. While homeless activists also advocated for more affordable housing, conservatives made sure that the “debate” about homelessness focused on camping and panhandling. And considering the number of homeless encampments and panhandlers in major cities, these issues easily overwhelmed discussions about homelessness as a housing problem. The public supported people getting affordable housing, but opposed camping and begging. Homeless advocates accepted the conservatives’ redefinition of homelessness and fought the battle on their opponents’ terms. It was a struggle they could not win.

San Francisco’s Homeless Problem

San Francisco has been a national model for addressing homelessness, and its experiences from the 1980s through today both foreshadowed and mirrors that of other cities. San Francisco is the nation’s most politically progressive city, a place where longtime Congress member Nancy Pelosi is more likely to be criticized from the left than the right. The successful reframing of homelessness from a lack of housing to a problem of individual behavior in progressive San Francisco explains why this strategy also found success elsewhere.

I head an organization that is San Francisco’s leading provider of permanent housing for homeless single adults. I have crafted city homeless programs and believe San Francisco is the national leader in housing the population my organization serves. But I know that tourists view San Francisco as having the worst homeless problem they have ever seen. People feel this way not because they have any knowledge of the actual numbers of people who lack housing or shelter, but rather because of the visibility of panhandlers, people sleeping in doorways, and problem street behavior in Union Square, on Fisherman’s Wharf, in UN Plaza, and along Market Street. These activities have come to define the city’s homeless problem. And using that frame, many San Franciscans join tourists in equating “combating homelessness” not with getting people housed, but with pushing panhandlers and those involved in “problem street behavior” out of sight.

I saw this turn in the framing of homelessness firsthand after Art Agnos became mayor in 1988. Prior to his taking office, I was among a group of homeless advocates who created a consensus proposal for a new direction in city policy. Calling itself the Coalition on Homelessness, the group (which later became an independent nonprofit) offered a concrete and specific program to an incoming mayor who had vowed during his campaign to change how the city treated the homeless. The Coalition’s proactive approach put Agnos in the position of having either to adopt a “ready to go” program or explain why it was inadequate. The group’s tactical activism ensured that its consensus proposal would be the starting point for all future discussions about homeless policy.

Ultimately, the city adopted almost every component of the consensus proposal. Whereas homeless activists in most cities in 1988 were still fighting for more emergency shelters, the thrust of the Coalition’s agenda was to divert funds from such stopgap measures toward transitional and permanent housing programs. The group’s analysis was adopted in San Francisco’s nationally acclaimed 1989 homeless plan, “Beyond Shelter,” written by Robert Prentice (one of the formulators of the consensus proposal), who was hired by Mayor Agnos to serve as the city’s homeless coordinator. President Bill Clinton’s homeless plan, as set forth in 1994 by Housing and Urban Development (HUD) undersecretary and current New York governor Andrew Cuomo, was essentially a redrafting of “Beyond Shelter.”

The Coalition’s proactive approach proved so successful an example of tactical activism that many of the plan’s authors, including me, became its implementers. I met with Agnos’s new social services chief, Julia Lopez, to urge the adoption of a modified payment program that would enable General Assistance recipients to obtain permanent housing at below-market rates. Based on discussions with hotel operators, I believed they would agree to lower rents and allow welfare recipients to become permanent tenants if the risk of eviction for nonpayment of rent could be reduced. The modified payment plan lowered this risk by having tenants voluntarily agree to have their rent deducted from their welfare checks.

Lopez told me such a program sounded great but that it would succeed only if the Tenderloin Housing Clinic ran it. We had never sought to run homeless programs, but I had spent years fighting the city’s practice of transforming single-room-occupancy (SRO) hotels into temporary lodging for poor people. We wanted to restore SROs to their historic status as homes for elderly, disabled, and low-income people and, not wanting to lose the opportunity to achieve this goal, we became a city-funded housing provider. As anticipated, landlords lowered rents so they could attract the formerly homeless tenants we could supply. The program was so successful that SRO rents fell significantly lower than they had been a decade earlier.

Agnos understood that homelessness was fundamentally a housing problem. But the city’s business and real estate community never liked Agnos, and storm clouds were brewing. On May 29, 1989, the San Francisco Examiner ran a front-page story in which business leaders denounced Mayor Agnos for allowing camping in the park outside City Hall. In what many believed was the greatest political error of his term, Agnos had decided to allow camping in this park until his programs creating alternative sources of housing were in place. As public anger over “Camp Agnos” grew, the mayor decided in July 1990 to cut his losses and sweep the park of campers. The purge became a national media story, as reporters found interest in a self-described “progressive” mayor’s cracking down on the homeless.

Because many of the campers had sought the now-independent Coalition on Homelessness’s assistance to prevent the sweep, Coalition staff workers entered the national debate in opposition to Agnos’s action, arguing that the mayor had caved in to political pressure and swept the park before his programs had become operational. The Coalition was correct about Agnos but failed to appreciate that his tolerance of camping had caused him serious political harm. The public never understood the rationale for allowing camping, and continuing the policy had become politically untenable. In their anger over Agnos’s betrayal, the activists rushed to defend the campers without appreciating the risk that their fight for more low-cost housing and mental health services would be reduced to a dispute over the right to camp in a public park.

The Coalition’s full-fledged attack on Agnos’s action was an entirely defensive response on behalf of people whom the public saw as voluntarily homeless. The residents of Camp Agnos typically wore backpacks and had chosen to sleep outdoors rather than pay rent in residential hotels. The Clinic’s outreach staff surveyed most of the campers and found that the majority received enough public assistance to pay rent if they so chose. In the public mind, people should be homeless only if they could not afford housing. Now the city’s leading homeless advocacy group was arguing that people who could afford housing had the right to forgo this option and instead live under the stars outside City Hall until temporary shelter or permanent housing was available to everyone. The public and media rejected, even ridiculed, this notion; accustomed to viewing homeless people as victims of hard luck, they could not accept the idea that anyone should reject shelter.

Most believed that Agnos could fulfill his responsibility to the campers by ensuring that each received a shelter bed or hotel room. The Coalition countered by urging sympathizers to “storm the park” so there would be more park dwellers than Agnos could immediately shelter. This strategy, a sudden, defensive response, understandably backfired. The media, though long sympathetic to homeless activists, interpreted this move as a blatant attempt to inflate the number of homeless denizens of Camp Agnos. The activists were even seen as interfering with the government’s effort to put a roof over people’s heads.

Agnos’s park sweep brought national attention unprecedented for a city homeless policy. From the New York Times to the MacNeil-Lehrer News Hour, national observers were fascinated by this action, taken by a mayor viewed as one of the nation’s most progressive. The publicity transformed San Francisco’s public debate about homelessness and led to the emergence of an entirely new model in cities across the United States. The model, honed by ambitious politicians and their corporate and media allies, creates symmetry between repressive political agendas and homeless advocacy groups: a mayor calls for a crackdown on “aggressive panhandling” and public camping; homeless advocates object on civil-liberties grounds.

When Agnos sought reelection in 1991, he faced a runoff against a former police chief, Frank Jordan. Jordan attacked Agnos’s “social worker” approach to homelessness and highlighted his own ability to get tough on individual homeless people by suggesting they be sent to work camps outside the city. Agnos got little political credit for providing thousands of housing units to the formerly homeless, and was instead condemned for allegedly allowing the homeless problem to get out of control. His defeat sent a powerful message to future San Francisco mayors: it’s fine to house homeless people, but voters define success by stopping public camping and related “problem street behavior.” Agnos laid the groundwork for the “housing first” approach to homelessness, which remains a national model, but some in San Francisco still believe he was a disaster in dealing with homelessness.

A Lost Opportunity

The 1990s proved an enormous lost opportunity for addressing homelessness. Bill Clinton’s election in 1992 brought a Democrat to the White House for the first time since the homeless crisis had begun. The nation soon had a booming economy that could have built all the low-income housing needed, yet the public debate about homelessness had already shifted. Emotional battles were fought, not over the nation’s affordable-housing shortage, but over the right to camp in parks and panhandle on city sidewalks. New York City mayor Rudy Giuliani won praise for reducing visible homelessness in his city, even though this “reduction” was achieved not by housing homeless people but by physically removing them from the areas of Manhattan frequented by tourists. San Francisco residents and politicians returned from Giuliani’s city marveling at the reduction in homeless people and wondering why they could not do the same. People compared San Francisco’s “failed” strategy with that of New York City’s “successful” one, as the criterion was not housing homeless people but getting them out of sight. Although Giuliani acknowledged upon leaving office in 2001 that New York City’s homeless numbers had risen during his eight-year tenure—despite great economic growth—his punitive methods became a “model” for other urban politicians.

By the 1990s, media sympathy for homeless persons had greatly declined. Media coverage of the homeless went from stories on recently unemployed middle-aged men to sound bites of long-haired, able-bodied young people confessing that they lie about being veterans so they can make more money panhandling. Panhandlers are no longer people trying to compensate for cuts in welfare checks; they are now drug addicts and alcoholics who use public charity to feed their habits. While positive stories are still reported about new housing and programs for homeless persons, stories connecting homelessness to the inability of millions of Americans to afford rent are eclipsed by those that separate the homeless problem from housing needs.

In “The Year That Housing Died,” the cover story of an October 1996 issue of the New York Times Magazine, author Jason DeParle claimed that “the Federal Government has essentially conceded defeat in its decades-long drive to make housing affordable to low-income Americans.” The federal budget included no new housing subsidies that year, and the 1996 Republican platform sought to eliminate HUD.

Can Proactive Homeless Strategies Still Prevail?

Have activists missed their chance to mobilize the nation to finally end widespread visible homelessness? It is hard to see how this goal can be achieved if advocates continue to allow issues like panhandling and camping to frame the debate. For example, since 2010, voters in some of the nation’s most progressive cities, including San Francisco, have enacted laws banning lying and sitting on commercial sidewalks. Opponents decry such “sit and lie” laws for “criminalizing homelessness,” while proponents argue that they target behavior, not homelessness. An October 19, 2012, New York Times story about a sit-lie ballot measure on Berkeley’s November 2012 ballot (“Free Speech Is One Thing, Vagrants Another”) profiled Chris Escobar, age twenty-three, “who left Miami five weeks ago” and “hitched a ride west with only a backpack, a yellow dog named Marley and a tiger striped kitten on a leash.” Escobar resented the idea that he was not free to sit on the sidewalk with his pets, and said about the ballot measure, “This is not the Berkeley I came for.”19

Young, able-bodied people like Escobar who spend their days sitting in front of small businesses and public buildings are not the part of the homeless population that most taxpayers desire to assist. They are perceived as choosing to be homeless and as hurting local commercial districts in the process. Unfortunately, this small segment of the homeless population continues to get much of the public and media attention. It does not represent the most vulnerable among the homeless; to the contrary, the young and able-bodied are often among the most self-sufficient. Yet activists continue to fritter away public support for helping the vast majority of homeless people, those desperate to obtain permanent housing, by defending a small subgroup that prefers to live under the stars.

Homeless advocates do not have to prioritize sit-lie, panhandling, and other quality-of-life issues. They do not have to be sidetracked from their core housing funding demand. Such issues can be addressed by civil liberties groups and legal organizations not involved in direct political advocacy for increased low-cost housing funds.

Activists still have a compelling case for increasing federal funding to reduce homelessness. San Francisco and other cities have reduced homelessness through a combination of housing and on-site services known as “supportive housing.” This successful model shows that ending homelessness is entirely a question of spending priorities. Reviving campaigns to invest in ending homelessness won’t be easy, but continuing to accept widespread visible homelessness in the United States is unacceptable. Ending homelessness remains a winnable national fight, but only if activists frame the debate around the millions of ill-housed eager to have a home.

CRIME FIGHTING: DEFENSIVENESS AT ITS WORST

Activists have paid the biggest price for responding defensively on the issue of crime. Unlike homeless activists, whose strategic errors never involved abandoning principles, some “progressives” zealously embraced law-and-order solutions to crime out of calculation and expedience. Other residents of low-income communities embraced longer sentences and prison expansion as part of a broader anti-crime strategy whose other key components, such as job training, housing, and education, were never implemented. Fearing being labeled soft on crime, many progressive politicians have backed the conservative framing of crime as requiring a “war on drugs” and the multibillion-dollar creation of a “prison industrial complex.” From the 1980s, when Republicans first saw the political benefits of promoting and maintaining a “war on crime,” through at least 2010, increased spending on prisons has diverted desperately needed money from schools, housing, and health care without making low-income communities safer. In fact, while states spend billions housing inmates guilty of nonviolent crimes, local police departments struggle for money to reduce crime at the street level.20

Defensive Crime Fighting in the Tenderloin

I became aware of the inherent strategic shortcomings of progressive-led anti-crime efforts from my own experience in San Francisco’s Tenderloin district. The Tenderloin has long been considered a high-crime neighborhood. After the rezoning battles of the early 1980s, the focus shifted to crime. Although most of the neighborhood’s crime involved property break-ins and disputes between drug dealers, enough seniors had been mugged or rolled to motivate people to organize an anti-crime campaign.

Because of these residents’ concerns, I became involved in the development of neighborhood anti-crime efforts. The Tenderloin Housing Clinic’s street-level office had relocated to a high-crime corner, so I needed only to look out our window to see why residents felt threatened. The primarily elderly residents of the Cadillac Hotel, located right across the street from our office, were particularly upset about drug dealing close to their building; some had been robbed right outside the gates. The hotel’s nonprofit owner, Reality House West, was headed by Leroy Looper, a charismatic leader and savvy tactician who had risen from a life on the streets and in prison to transform the Cadillac from an eyesore to a neighborhood jewel. Looper responded to his tenants’ complaints about crime by forming the Tenderloin Crime Abatement Committee (CAC). The CAC met monthly at the Cadillac Hotel. When Looper asked me to participate, I readily agreed. At the time, I was almost alone among progressive social change activists in getting involved in anticrime efforts. Gradually, however, Looper brought in representatives of religious groups, refugee organizations, and other social service agencies.

In addition to my admiration for Looper and desire to support residents’ concerns, what attracted me to the campaign was the high percentage of African Americans participating in the CAC. The Tenderloin’s African American residents had participated little in the long-running land use battles, and I thought their involvement in anti-crime efforts might encourage community participation in other issues. The fact that Looper and key Cadillac Hotel management staff were African American contributed to the CAC’s high level of ethnic diversity.

During 1984 and 1985, I regularly attended CAC meetings and ended up presiding over many of the meetings, which were festive occasions. A Cadillac Hotel resident would prepare a buffet lunch. Everyone in the audience had the opportunity to comment on the issues being discussed, and the district police captain and beat officers would provide updates on crime statistics and respond to concerns raised at the meeting. The CAC reflected the type of ethnically diverse, broad-based community empowerment effort that social change activists in all fields aspire to create. The committee stressed the need for employment, training, and substance abuse programs and for other strategies that would address the underlying causes of crime.

There was a consensus, however, that until such systemic programs were in place, a stronger police presence was necessary. Many of us naively believed that the Tenderloin residents’ opposition to crime in their community would bring increased government funding for programs to ameliorate the preconditions causing high levels of crime. Looper, the community’s most revered leader, always saw economic development and increased local employment as key to reducing neighborhood crime. The CAC was not demanding more police simply as a tactic for obtaining economic development assistance; rather, we believed that expressing serious concern about crime would stimulate a broader influx of resources into the Tenderloin.

The committee decided to publicize the community’s resolve with a “March Against Crime.” Marches are now commonplace in low-income neighborhoods, but such events were somewhat rare in 1985, and we expected—and received—tremendous media coverage. One goal of the march was to demonstrate that the Tenderloin was a residential neighborhood whose residents and businesses deserved the same level of police services as inhabitants of other communities received. We also sought to show that the Tenderloin housed victims of crime, not simply perpetrators. As long as the public believed that Tenderloin residents were themselves to blame for crime, and thus tolerated thefts, drug deals, and muggings, there would be less support for anti-crime measures and other programs designed to help the neighborhood. The march was the perfect tactic for a community trying to reverse long-held but erroneous public attitudes about it.

CAC activists were thrilled by the success of the event. We felt the march had not only accomplished its goals but also galvanized community activism around fighting crime. Attendance at CAC meetings increased steadily, and it seemed as if police visibility rose in the area. Crime appeared to be the new issue necessary to maintain resident activism after the historic rezoning victory. The North of Market Planning Coalition began increasing its emphasis on crime, which soon became its chief focus and organizing vehicle. A Safe Streets Committee was formed. Although it was unclear whether the neighborhood’s anticrime efforts were actually reducing crime, many residents felt empowered because top police brass appeared to take their concerns seriously.

By 1987 we still had not received the hoped-for assistance for attacking crime’s economic underpinnings, but most of us attributed this lack to the pro-downtown policies of the reigning Feinstein administration. We believed that a new, progressive mayor would deliver neighborhood-oriented economic assistance to the Tenderloin, and when Art Agnos succeeded Feinstein in January 1988, we all thought the Tenderloin was poised for a major turnaround. I shifted away from the crime issue after 1986 and returned to focusing on housing and homelessness, but I continued to support the neighborhood’s campaign against crime and won a formal commendation in 1986 from the San Francisco Board of Supervisors for my crime-fighting efforts.

On March 1, 1990, Mayor Agnos announced that a police station would open in the Tenderloin. I was initially excited by the announcement, as the community had finally received something tangible after years of anti-crime advocacy. I saw the police station as a building block that would be followed by additional government efforts to improve the neighborhood’s social and economic climate. But I soon learned that the police station was all the Tenderloin would ever get.