Читать книгу The Girl with Braided Hair - Rasha Adly - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление7

Cairo: Autumn 2012

Her alarm woke her from a dream. The hands of the clock read a quarter to seven. She had a class at 8:30. Sluggishly, she pushed the covers off herself and yawned and stretched like a lazy Persian cat. Sleepy-eyed, she padded to the kitchen, flicked the electric kettle on, and shoved a cheese sandwich into the toaster. She was exhausted; the discovery she had made the previous day filled her with so many questions that she hadn’t slept all night. She had to find answers.

Quickly, she dressed in something suitable for work. She disliked formal attire, much preferring jeans, a T-shirt, and some sneakers, but a university professor must appear conservative. Therefore she followed the Egyptian proverb, “Eat what you please, and wear what pleases others.”

She looked into her grandmother’s room with a cheery “Good morning.” Receiving no reply, she watched her chest to make sure it was still rising and falling. She was always haunted by the fear that the old woman would have a heart attack and die in her sleep. Relieved, she packed some papers into her briefcase, swallowed down her sandwich, and went out, travel mug in hand. As Yasmine was waiting for the elevator, Fatima, the Nubian-Egyptian maid, came out of the service entrance as she had been doing for more than a quarter of a century since she started working for them; she refused to use any other door, although the service staircase was long deserted and inhabited only by stray cats. Even the newspaper man and the milkman used the elevator: only Fatima insisted on using the service stairs. She was continuing the journey her mother had started half a century before, when she had first gone into service with Yasmine’s grandmother. She used to take her up the service stairs with her as a little girl, and thus she never used any other. She belonged to the ‘servant class’ that used to exist in bygone days, the people who bowed when serving the coffee, and used ‘Sir’ or ‘Madam.’

The weather was crisp with spring, encouraging her to walk to the Faculty of Fine Arts, only a few streets away from her house. She needed time to collect her thoughts and exercise in accordance with Nietzsche’s maxim, “Great ideas come to us while walking,” but she was only preoccupied with one idea, one painting, one girl, one artist.

In class, she stood distracted at the slide projector, hardly able to see the painting before her for her mental image of the girl. They merged in her mind, although they were completely different. “Look at her thick black braids,” she said, pointing to the hair of the model in the painting.

“What?” The students murmured loudly.

Yasmine blinked. There were no black braids; the painting was of a blond with her hair up and a hat on her head. “Excuse me,” she said, shaking her head. “I meant, look at the way her hair is arranged and the design of the hat, a look popular in nineteenth-century France.”

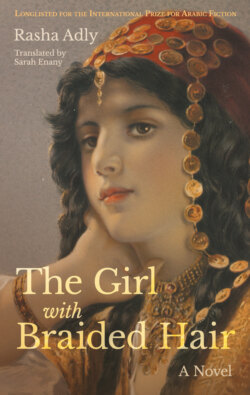

As soon as the lecture was over, she went straight to the Conservation Department. She sat a few meters away from the painting and tried to view it with the eye of an ordinary viewer. The girl’s features combined innocence with seduction: there was a promise of something in her eyes. The gold hoops in her ears indicated that she was from a wealthy family. Her lace scarf was draped around her shoulders, her black braids peeking from underneath it. That fabric was unknown to Egyptian women of the era. Her gallabiya was black, with vertical stripes of red, gold, and blue. The artist had paid attention to all of these small details, to the features that mingled innocence and seduction, good and evil. Which of them did he mean to portray?

The voice of Professor Anwar jolted her out of her thoughts. “Still staring at that painting? Is it really that much on your mind?”

“Yes,” she responded.

“Tomorrow we’ll take it down to the infrared lab.”

She smiled at him gratefully.

After class that day, she wrapped the painting carefully, obtained a permit to remove it from the premises from the head of the Conservation Department, and took it home.

Fatima knocked on the door to her room. “I’ve done the housework, fed Madam, your grandmother, and given her medicine.”

“Thank you,” said Yasmine. “I don’t know what I’d do without you.” The compliment was by no means an exaggeration: Fatima relieved her of a burden she was incapable of shouldering.

At six, he called to invite her out to dinner, “unless you have plans tonight.”

“I don’t have any plans.”

“How would you feel about going out for pizza?”

“Pizza?” she repeated slyly.

She was well aware that since their breakup, he would never say he wanted to see her, and would never call to tell her “I miss you” or “I need to see you.” All he would say was “I’ll be there at such and such a time, if you want to join me,” and give her the freedom to come or not as she chose. There had been a time when the relationship they shared gave him the right to demand her company. Now he had no excuse. She knew perfectly well what he was thinking. “No, I don’t feel like pizza tonight. I’ll come by the restaurant at nine and we can take a walk together. That’s what I really need.”

“I’ll be waiting.”

She pulled on something from her closet, a short wool dress, and put on a coat over it, leaving her hair loose and only putting on some kohl and lip gloss. That was all she needed when she went out to see him, for with him, she could be herself. That was the best thing about this relationship, to feel this close. She never felt the need to put on a mask to meet him, or pretend when talking to him.

Pizza Thomas was a few streets away from her home in Zamalek, and had been there since the 1950s. Its owner had preserved it perfectly in its original vintage style. The kitchen was open onto the dining area: you could watch the pizza cooks rolling the dough and pressing it into the dishes, then putting the ingredients on top of it and sliding it into the oven. It gave the place a perpetually warm and delicious smell. She approached the glass front of the store through which the tables and customers were visible. She saw him at his usual seat, and waved at him to come out.

Outside, he put an arm around her and they walked together: sidewalk followed sidewalk and street followed street. Each street had its own smell; each path sounded different as feet displaced tiny stones. Now they were face-to-face with the Nile. He sat on a bench facing the river and lit a cigarette. “Something on your mind?” he asked.

“Yes,” she replied. “You remember the girl I was talking to you about?”

“What girl?”

“The girl in the picture.”

He let loose a hearty chuckle. She had always loved his laugh: he threw his head back and looked up and laughed long and loud, making it impossible not to share in his merriment. “What are you laughing at?”

“This!” He pointed to her head. “This head of yours!”

“Oh?” she said coolly.

“You leave the here and now and go running after the past.” He let out another laugh. “My dear, it’s just a face in a painting, and you’re spinning tall tales about it! She’s just another Egyptian girl, like any other girl. The artist saw her, and fancied her, and painted her. There’s nothing more to it.” He took a deep breath. “You’ve got your life ahead of you, clear, transparent, waiting. Why do you run away down the corridors of the past?”

“Well,” she retorted, “If she’s just a regular girl, why would the artist weave locks of her hair, human hair, into the pigment he mixed with the color for her braids? Tell me there isn’t a secret behind that girl. Why would he do that?”

Sherif sobered. “True. Why would he do something like that?”

“I’ve got the painting at home. Come,” she said eagerly, “let me show you.”

“Now?” he protested, looking at his watch.

“Yes, now.”

Yasmine took his hand and they walked to her building. When he saw it, the architect let out a long, low whistle in admiration of its Baroque architecture with the double entrance, one leading onto the main road, and the other into a side street. She smiled, knowing how much he liked it. On the inside, it was even more like an ancient castle: the stairs were polished marble, the banister wrought-iron. He refused to take the elevator, choosing instead to walk up the stairs: “I don’t trust elevators. They make me claustrophobic.”

“Me too.”

The echo of their footfall on the marble staircase was loud in the silence; it seemed wrong to speak in such an atmosphere. Many of the older apartments in the building were uninhabited thanks to the outdated rent-control laws that plagued Zamalek and other quarters full of historic buildings. As a result, walking through the building was like entering a place where time had stopped—locked into the old, empty apartments.

The sound of a television reached them from behind Yasmine’s door: her grandmother was used to turning it up loud. When they went inside, she hung up her coat on the rack and asked him to wait in the entryway. He could see that the apartment was a lot like her, plain and simple. It was easy to tell that an artist lived there from the paintings hanging on the wall and the artwork on the tables. Everything was quiet, except for the din from the television. Her grandmother ignored her: she was watching a televised black-and-white recording of an old play and guffawing loudly. Yasmine picked up the remote and turned down the sound, bending to speak in her ear. “Grandma, we’ve got company. A colleague, here to see a painting.”

The old woman’s face filled with astonishment. “Well, do let him come in—no, wait! Do I look presentable?”

“Yes, Grandma.”

The old woman wrapped her shawl around her shoulders tightly and touched her braids to make sure they were straight. “This is Sherif, he’s an architect, Grandma.”

He bent to shake her hand: she peered at him with the unabashed curiosity of old age, scrutinizing him from head to toe. Yasmine went to the kitchen and came back with a glass of orange juice. “Here you are.”

Her grandmother looked disapproving. “Go and put on a nice dress and some makeup!”

“There’s no need.”

“But your fiancé shouldn’t see you like that!”

“My fiancé?”

They exchanged a smile while the old woman went on. “You’re over thirty! And you, young man, how old are you? You look over thirty too. What are you waiting for? In our time, folks your age had grandchildren.”

He smiled. “I’m quite happy to go ahead right now, but Yasmine is otherwise occupied. When she’s free, we can decide on a wedding date.”

“I’m taking our guest to my room,” said Yasmine, having had enough of this, “to look at the painting.”

Her grandmother didn’t look too pleased at the idea of her granddaughter taking a strange man into her room, even her future husband, but finally agreed.

Yasmine walked ahead of Sherif, heels clicking tensely on the wooden floor, down the long corridor that led to her room. “Why did you tell her that?”

“Tell her what?”

“That we were going to get married.”

“Because she wouldn’t have listened to anything else.”

Yasmine opened the door and stood facing him. “You don’t know Grandma. Starting this minute, she’ll be planning the wedding. And she’s not going to stop asking me about you, day after day after day.”

“You can just tell her anything. . . .”

“Anything like what?”

“Uh, that you found out I was a lowlife. That I dumped you and left the country. Or found another woman. Or told you it wouldn’t work out between us.”

She could see what he was getting at, so she cut off the conversation so as not to start a fight; she had quite enough going on. Standing directly opposite the painting, she gestured to it. “Here, look.”

He looked at it for a few minutes. “It’s quite unremarkable,” he said, “if you look at it like a regular viewer. One of the Orientalist paintings they left behind to show they were here. A girl, like hundreds of girls.” After a moment, he added, “Maybe a touch of something . . . in her eyes. Like a glow. Makes you feel she’s still alive and looking back at you.”

Yasmine listened to him, nodding, certain that what he said was true: there was nothing about the portrait that would strike the fancy of an ordinary viewer. Just a girl in a black gallabiya with vertical stripes, a lace scarf covering the front of her head and shoulders, braids emerging from beneath, hands folded over her midriff.

Sherif stepped closer to the painting and reached out to touch the girl’s braid. “If it wasn’t for that lock of hair,” he murmured, “I would have said you were imagining things.”

“The minute I saw that painting,” Yasmine nodded, “something told me there was a secret behind it.”

She was still gazing at the portrait, while Sherif looked around him. Her room was different from the others in the house, a thing apart: everything in it seemed to belong to a girl of fourteen. The white furniture, the patterned wallpaper, the pink curtains, the giant dolls, everything was as cheerful as she could possibly make it. Nothing about the room said ‘Art History Professor.’ Still, it was the other face of her, the child inside.

He reached out and picked up a photograph from the bedside table. It was a picture of Yasmine with her family when she was about ten years old. Next to her stood her sister Shaza, the height difference making it clear that the latter was several years older. Behind them, their parents stood, her father’s arm around their mother, both smiling. “You look a lot like your mother,” said Sherif. She said nothing, but gave him a wan smile. “Your eyes are the same, and you have the same smile.” He replaced the photograph. “You never talk about your family.”

“You know all there is to know,” she snapped. “My mother died years ago. My father left to go work abroad not long after. Shaza went to study in England and eventually found work there. Is that enough or do you want more?”

“Well . . .”

She rounded on him. “Let me tell you.” She stomped over to the picture and snatched it from him. “To see him like this,” she stabbed a finger at her father, “his arm around her like that, you’d say they were the perfect couple. To see her smiling like that, you’d say she was the happiest woman in the world. And you’d call me and Shaza lucky girls with a bright future ahead of us. That’s always what the pictures tell you.” He opened his mouth, but she plowed on. “The reality isn’t quite like the photos. That man in the photo,” she gestured violently, “made that woman kill herself. He made her slit her wrists with a razor because he cheated on her with her best friend. She died. He left. These two girls were left with nothing but grief. One of them couldn’t stand to live in this country any longer, so she packed up and left for somewhere far away where she knows nobody and nobody knows her. The other is . . . as you can see.”

He stood there, speechless. He knew that all the words in the universe could not take away her grief or console her. He felt an overpowering urge to hold her close and make it up to her, all the years of unhappiness. Taking the photograph from her hand, he gently replaced it. Then he put his arms around her. Her body was warm and fragile, her heart beating an anxious tattoo. She stayed in his arms for a while, trembling as he tried to comfort her. Then, with a quick kiss on the cheek, he left.

Cairo: August 1798

Zeinab could hardly believe it. Had she been sitting next to Bonaparte himself? The man whose very name made the strongest men quake in their boots? Had she been sitting side by side with him? Had the man himself taken her hand and closed her fingers around the gold coins he had given her? And what was more, he had asked her father to bring her with him the next day! Had that really happened, or was she dreaming?

She strutted proudly as she walked: and why not? She was the woman who had sat next to Napoleon in his seat in the royal marquee, watched by the aristocracy, the mayors of all the towns, the imams of al-Azhar, the most important merchants, the common folk, and everyone, all of them asking, “Who’s that girl sitting at Bonaparte’s side?” When she stepped into the horse-drawn cart that would take her and her father back to their street that day, the men glared at them with envious resentment, while the women gathered behind the meshrabiyehs watching the girl who had captivated the emperor. All of a sudden, for the first time, Zeinab felt that she had left her childhood behind and become a lovely young woman, capable of charming men and making them admire her. At home, her clogs beat a tattoo on the wooden floor as she repeated a poem someone had composed especially for him:

The chivalrous Bonaparte, leonine and most capable in the land

Has conquered kingdoms and his will is done with a wave of his hand.

After the afternoon prayer, she went out with some of her girlfriends. Her mother put the gold coins that Napoleon had given her into a burlap purse which she bound with strong thread and secreted inside her gallabiya, and she went shopping. Now she could shop at the stores that only sold European wares, imported and brought in on ships over the Mediterranean from Spain, France, and Greece: wool, carpets, shawls, gold watches, perfumes—the gold coins gave her the right to purchase from such stores, not only browse regretfully as she had used to.

Since Napoleon’s campaign, the stores had taken to hanging out their shingles in French, and the narrow alleys were bursting with French soldiers, some of whom enjoyed taking walks on foot, looking around at everything warily, and some of whom hurried by on the backs of mules, which occasionally crashed into each other. It was impossible to deny that conditions in the country had improved under the French compared to the Mamluks: the streets were clean, thanks to the first decree issued by Napoleon, that the streets were to be swept and watered down every day. The folk who used to throw their refuse and the remains of the animals and birds they slaughtered into the street were now careful to throw them away in a remote location reserved for the purpose. The brawls that used to break out every moment throughout the day were completely extinct now, thanks to the powers of the French troops in breaking up fights between ex-convicts, carters, and those who rented beasts of burden. Anyone fighting would be immediately taken off to the police station to receive a stern punishment. Suddenly, the tradesmen kept to posted prices and were careful to provide quality goods. It was a truth that could not be denied: things had changed for the better under the French.

With pride, Zeinab said to her friends, “Look around you! Can you say we’re not better off under the French than the Mamluks? It’s enough that it doesn’t stink and there aren’t piles of garbage at every street corner.” She waved a hand. “Look, everyone seems more cheerful and their clothes are cleaner.”

“Do you think it can go on? People won’t keep doing a thing if they’ve been frightened into it,” a friend replied. “It just breeds resentment. Someday, it’ll all blow up.”

Zeinab laughed mockingly. “Since when have we not been frightened into doing things? At least being afraid has actually gotten us something useful, for once. Before, all we had was ignorance and disease.”

“I don’t understand you, Zeinab! Are you really on the side of the invaders? Can’t you see how unfair and cruel the Frenchmen are to us Egyptians? Haven’t you heard of the massacres that happen every day, of them cutting off people’s heads and mounting them on pikes on the walls of the Citadel? What about the bodies in sacks that they throw into the river?”

Zeinab ignored her: she had caught sight of a shop displaying velvet and silk imported from Malta and France. Darting inside, she touched the fabrics, wrapping them around her body. “How gorgeous. I’m going to buy it.”

When she came home, laden with her purchases, a crowd of people was there: clerics, imams, instructors from kuttab Qur’an schools, and blind Qur’an reciters, all standing outside the house of Sheikh al-Bakri to complain. Apparently, they had been fired and their salaries cut off because the Ministry of Religious Endowments had been taken over by the Copts and Levantines appointed by the French. “Now what do you have to say?” asked her friend, gesturing to the throng outside the door. “Now that’s injustice if ever I saw it.”

Zeinab ignored what was happening, so thrilled was she with her purchases from the market that she had bought with the gold coins Napoleon had pressed into her small hand. Wonder of wonders! She had bought everything she had been longing for and still had money left to spare.

She kept rubbing her palm, remembering how he had touched her hand. She couldn’t sleep at night, wondering: had she really been touched by the Emperor of the East? Had the look in his eyes, which had held so many words and so much meaning, truly been for her? Was it possible that he had come to conquer Egypt so that fate might bring the two of them together? Were the distances he had traversed to reach this land and all the cities he had conquered on his way, all the battles he had planned, stepping stones to her fate to meet him, pressing gold coins into her hand, enfolding her with his smile?

She hardly noticed her mother opening the door to her room: she was soaring in the world of her fancies. “What’s come over you, Zeinab? It’s like you’re not even here.”

“What happened to me isn’t just any old thing. Bonaparte the Commander put gold coins into my hand and smiled at me. He told Father to bring me along when he goes to meet him tomorrow.” She sighed. “And then you ask what’s come over me?”

“So what?” her mother said. “Don’t let your imagination carry you to flights of fancy. Next you’ll be telling me you think he fell for you. You’re nothing but a child to him. You’re the child of the man he trusts.”

But she did not let her mother’s words quell her joy. “Poor Mother!” she murmured under her breath. “You didn’t see the way he looked at me.”

Ponderously, her mother waddled to the bed where Zeinab had piled up her purchases, and began to look them over. “Lord, what glaring colors!” she rebuked. “And this fabric’s transparent! Have you lost your mind? Zeinab, daughter of Sheikh al-Bakri, wear something like this? Do you want tongues to wag?”

“Mother!” Zeinab groaned. “Please, just for once, forget, or pretend to forget, that I’m Sheikh al-Bakri’s daughter! I’m Zeinab! I can do what I like and wear what I please!” She straightened. “Besides, people will talk no matter what you do or don’t do. Everyone loves to gossip.”

“Well, I’ll tell your father, and he’ll deal with you.”

That night, in a spacious bedroom on a brass bed, the portly body of the Sheikh’s wife tossed and turned, sleepless. The bed wobbled and squeaked. “Lord,” she groaned in disgust, “I’m drowning in a soup of sweat.” She heaved herself up and went to open the meshrabiyeh a little, hoping to let in a cool summer breeze for some relief from the stifling air of the room. A little before dawn, she heard the sound of her husband’s sandals sliding across the reed mat. She raised her head and watched as he took off his large green turban and hung it on the clothes rack, then got up to help him take off his caftan—the new one that Napoleon had given him.

“You should discipline your daughter. She’s too impulsive,” she started. “I don’t know what’s come over her, but suddenly she can’t be controlled.”

He guffawed. “Let her do what she wants,” he reassured her.

“What’s that you’re saying? How can I let her do what she wants?”

“Have some discernment,” he smiled, “don’t be thick-headed, there’s a good woman. I have something in mind. If it comes to pass. . . .” He stroked his beard, which grew down to his stomach.

“What’s that supposed to mean? What are you talking about?”

Maliha, the slave, walked in with a jug of warm salt water, and placed it at his feet. She washed them, then dried them with a towel. “When the time is right, I’ll tell you everything.”

His words only perplexed her more. She could not fathom what her husband could possibly be thinking.

The next morning, Zeinab woke early. She had only slept a little that night, preoccupied. Maliha prepared a bath for her: she placed the urn of water on the brick oven and, when the steam rose from it, scrubbed Zeinab’s body with a rough loofah made of sheep’s wool, poured water over her head, and massaged her scalp and hair with a bar of soap made from olive oil to make it smooth and silky. Then she rinsed her off with clean water and perfumed her with musk and ambergris, and finally sat braiding cloves into her hair to make it smell sweet. When she was done, she smiled at her and spat at her side three times for luck, spraying granules of salt around and saying, “Lord protect you from the Evil Eye!”

To Zeinab’s eyes, there was something odd about Maliha today: she seemed to be sad for some reason. Usually, she never stopped talking and joking, but today she had hardly said a word. “What’s wrong, Maliha?” she asked when they had finished.

“My master Sheikh al-Bakri told Rostom to pack. He’s going to make a present of him to Commander Bonaparte. He doesn’t want to go. But my master the sheikh insists on it.” Her tone turned pleading. “Could you speak to him, Miss Zeinab? He won’t say no to you.”

Does Father really want to give our Rostom to Bonaparte? Zeinab thought to herself. He has been indispensable to Father since the moment he set foot in the house—he does everything, from going to market and taking care of my brothers and doing the carpentry and plumbing work in the house and even helping with the baking, to gardening and overseeing the vegetable garden, and he guards the house at night as well. She drummed her fingers against her chin. Besides, he’s my father’s most trusted servant and keeps all his secrets. Could her father sacrifice all of this and present Rostom to Napoleon?

“I’ll speak to him,” Zeinab finally said. “Now let’s see what I’m going to wear.”

Zeinab stood at her closet. It was made of beech wood, designed by a carpenter from Malta, and ornately decorated, with brass handles. She wondered what to wear to such an occasion: even if it was just a routine meeting like the ones Napoleon held every day for the important men, the guild masters, and the Azharite imams, it was enough that she was to be a guest in the house of Napoleon, who had insisted that her father bring her with him.

She selected a gallabiya with vertical stripes, tight and alluring around the contours of her body. She put on her curl-toed slippers and perfumed herself. The sobs of Rostom rang out loudly as he stood in the courtyard holding his clothing in a sack and saying goodbye to everyone. Zeinab approached her father and whispered in his ear, “Can’t you leave him be?”

Angrily, he swept his caftan up over his other shoulder. “No. He’s my gift to Bonaparte, who needs him more than I do.”

“But I don’t know anyone here but you,” sobbed Rostom. “I served you with everything I had. You were my family.”

“Your star shall rise in the house of Bonaparte, believe me,” said her father. “You are a slave trained to be a professional warrior. It’s a shame for your talents to be wasted in buying vegetables from the market and watering the garden.”

It was clear that Sheikh al-Bakri had made up his mind, and Rostom could see that it was no use arguing. He had not the right to decide his own fate: his destiny had always been in the hands of others, since the long-ago day he had been loaded onto a ship to be taken to Constantinople and sold at the slave market. There, he had been bought by a rich merchant who had gifted him to a friend of his a few months later, and that man in turn had taken him to Egypt and gifted him to Ibrahim Bey, a Mamluk prince. The latter had trained him to fight in his division, teaching him the art of mounted combat, until he rose to be a formidable warrior in the Mamluk army. But fate is fickle: the winds of change arrived in the form of the French Campaign, blowing away everything in their path. The Mamluks ran away and dispersed through the cities of Egypt, and Rostom ended up with Sheikh al-Bakri, who had been friends with his owner, the prince. He had promised the latter to make Rostom his servant and faithful guardian—and Rostom was faithful and loyal in every sense of the words.

Sheikh al-Bakri mounted his horse and Zeinab a mule, while Rostom dragged his feet weakly in their wake—Rostom, who used to run like the wind—his sack of clothes in hand. His tears flowed more copiously with every step he took away from the house, toward an unknown fate with this man who killed and slaughtered without compassion or mercy.

They turned toward Ezbekiya and crossed the bridge leading to Harat al-Ifrinj, the Alley of the Franks. On the way, they saw the Mamluk palaces and mansions that the French had appropriated for themselves, plundering their precious booty. Here the Mamluks had lived; here was the house where Rostom had lived with Ibrahim Bey, one of the most famous Mamluks, the center of attention in every street and marketplace. No sooner did he set foot outside than everyone would start to stare at his opulent clothing, his horse adorned with silk and gold. His spacious mansion had been transformed into a restaurant for the French, a sign on the door saying, “All French dishes are prepared by a French chef.” He peered inside to see the tables and chairs laid out in the garden with peerless elegance—an elegance unknown in Egypt at that time, where people ate with their hands, dipped their fingers in dishes, chewed loudly, and were not ashamed to release the occasional loud belch.

They stopped at the place where Napoleon lived, by the lake Berkat al-Rathle. Guards in military uniform surrounded the palace on all sides, wearing feathered hats, weapons hanging at their sides. They looked incongruous, as though they had been placed in this location by mistake. Sheikh al-Bakri received permission from the guards to enter. They told him to leave the horse and mule outside, which he did, and they entered on foot.

They walked through the gates into a spacious garden filled with flowers whose perfume wafted everywhere. In the center was a mosaic fountain inlaid with Damascene tiles. The instant Zeinab and Rostom stepped into the garden, they trembled, and their heartbeats sped up with fear and trepidation. Neither knew what fate awaited them within the palace walls.

The place was labyrinthine: rooms within rooms, corridors leading onto corridors, entrance halls that were alternately broad and narrow. The floors were smooth marble and the windows were inlaid glass. In the central atrium, soft seats had been placed all around to receive guests, while in one corner was the large conference room where Bonaparte held his meetings.

The palace was bustling with activity, busy as a hive of bees, filled with soldiers coming and going in shiny black boots, footfalls loud where they trod on wooden floors. Her father perched on the edge of the couch, while she stood at his side like a frightened squirrel, Rostom behind them. They were not the only people awaiting an audience with the great man; a great many Azharite imams and religious scholars were lined up in rows, some barely concealing their resentment and hatred behind the mask of a false smile. Their eyes raked over her, one question evidently in their minds: What brings her here? She looked at the floor and shuffled behind her father’s bulk.

A loud noise burst through the atrium, and Napoleon strode in, flanked by his officers. He greeted everyone in French, whereupon some of those present remained silent and others tripped over their own tongues. Catching himself, Bonaparte made a visible effort to recall the few words of Arabic he had memorized and, in a French accent, said, “al-Salam alaykum wa rahmat Allah wa barakatu,” peace be upon you, and the Lord’s mercy and His blessing. Zeinab could hardly keep herself from laughing, and she could not suppress a small giggle.

Bonaparte went to her, took her by the chin and raised her face to his. The murmurings of the men grew loud and resentful as if to say, “Have some decency! You have an audience!” Bonaparte’s eyes then fell upon Rostom.

“This is the boy I told you about,” said Sheikh al-Bakri.

Napoleon nodded without speaking. He spoke softly to one of his guards, then turned and headed for the conference room, the assembled crowd following him. Zeinab was so confused she had no idea what to do, so she followed them with hesitant steps. When she tried to enter the conference room, the guard to whom Napoleon had spoken barred her way and told her to wait outside.

The guard disappeared for a moment down the corridors of the great palace, then reappeared in the company of a Frenchwoman. Her face betrayed nothing of her age. She appeared serious and stern, looking Zeinab up and down from head to toe. Then she let loose a torrent of incomprehensible French, as though something had irked her. Zeinab had no idea why the woman was speaking, but a look at her face was enough to tell that she was displeased. With a haughty gesture, the Frenchwoman motioned to Zeinab to follow her.

Zeinab followed the woman down a set of marble stairs that led to a long corridor, to the right and left of which were closed doors, rooms concealing their secrets. The woman took her into one of these: inside were several sewing machines and long tables with sewing equipment on them: scissors, needles and thread, fabrics of every type and description, and a boxful of the feathers used to decorate the soldiers’ hats. If one fell off, Zeinab thought, they would have no trouble finding a replacement.

Zeinab stood before the woman, who took her measurements without saying a word. Zeinab loved to joke and laugh, and she knew that if she had been at her own seamstress’ place, she would have filled the room with giggles and good-natured fun. But with this woman, it was different. She finished taking her measurements and commanded her to go. The guard was still waiting for her. All Zeinab could think about was the clothes the woman would make for her. Would she make them like the ones worn by the French women, the long, puffy dresses that made them seem as if they were floating? Could her dream really be this close to coming true? She had only recently been wishing to be rid of this hateful gallabiya she was draped in, and wear a dress like theirs!

The French soldier marched on, and she followed him to what fate she knew not. What was Bonaparte preparing her for? The guard led her into a room with bookshelves lining the length and breadth of the walls, laden with Arabic and French books and magazines. The air smelled of books and burnt pig-tallow candles. Several Frenchmen were sitting at a large reading table, half-hidden behind stacks of books. In a corner was a desk with an elderly man sitting at it. He appeared to be a man of great knowledge, dressed in the French style, what was left of his white hair tied back in a ponytail. He appeared both serious and kindly. The guard launched into a long conversation with him, and when he finished speaking, the man looked long and hard at Zeinab. Then he smiled. “Welcome,” he greeted her in Arabic.

“Thank you,” she replied.

He motioned her to a seat. “What is your name?”

“Zeinab.”

“Do you know any French words?”

“No.”

“Right. You’re here because General Bonaparte has asked me to teach you French, at least a few words, so that you can speak with him.”

Her jaw dropped. “So you can speak with him”? She repeated the phrase over and over in her head, asking herself, Am I going to speak with him?

The kindly old gentleman seemed to notice that the girl was perturbed, and smiled to calm her down. “Don’t be afraid. French is simple and easy. You’ll like it. Now, come on, we’ll start our first lesson.”

Meanwhile, Rostom was still waiting outside the conference room, bundle in hand, just as the guard had told him to. Everyone who came and went stared at him, for his incongruous clothing, the sack in his hand, and the place he was standing in were all conspicuous and piqued their curiosity. Hours later, when the meeting was over and everyone had left, Napoleon sent for a guard to bring Rostom in. He was still standing in place, not having moved an inch.

Rostom stepped into the conference room, finding the great man standing at his desk with Sheikh al-Bakri. Napoleon examined Rostom carefully, then asked, “What’s your name?”

“Rostom.”

“Where are you from, Rostom?”

“I’m from Georgia. I was kidnapped as a child from my family, and sold and resold several times, until I wound up in Egypt.”

“Are you an adept fighter and horseman, Rostom?”

“I am a Mamluk of the class that is trained in the arts of battle. You are aware that ordinary Egyptians are not permitted to bear arms, but I am. My specialty is mounted combat.”

Napoleon went to a closet and took out a magnificent sword with a diamond-studded hilt, and two pistols with worked gold handles. “From now on, you shall be my personal slave and my loyal guard.”

Rostom nodded without speaking: his trepidation had swallowed up his words. Sheikh al-Bakri rose and patted him on the shoulder. “I hope you won’t let me down,” he said.

That was their first meeting, Napoleon with his low, soft voice and perpetually furrowed brow, and Rostom with all the questions he kept locked inside as to the mysterious fate that had propelled him through time from place to place, to finally bring him face to face with the most powerful man in the world—to be given a diamond-studded sword the like of which he had never imagined to own in all his life, and what was more, to be his personal guard and protector.

Napoleon left his tent, and Rostom exited to be initiated into his new profession by a guard, while Sheikh al-Bakri sat in the atrium waiting for his daughter, swallowed up somewhere, he did not know where, in this wonderful palace.

More than three hours passed with Zeinab in the company of the elderly gentleman, absorbed in teaching her French. He wrote out the letters of the alphabet and read them to her, asking her to repeat after him; he had her copy out each letter; then he asked her to try and pronounce his name. She was a quick study in copying the letters, although it took her a long time to learn how to hold the quill and dip it into the inkwell, then use it to write. The strange thing was that, although she was usually by no means patient, the hours did not drag on her and she felt no tedium; on the contrary, she felt full of enthusiasm. Her eyes shone with an unusual light, and her smile broadened whenever he said to her, “Bravo!”

Finally, the man folded up the papers and held them out to her, together with the quill and the inkwell, and asked her to memorize them like her own name. “I’ll expect you in three days, same time, same place.”

She thanked him and walked out of the library, weighed down under her pride. She was on her way to being special, and the knowledge filled her with delight. The guard, who had been waiting outside the library, took her back to the atrium, where her father waited. She looked around, searching for the emperor, but he was nowhere to be found.

On their way out, Sheikh al-Bakri asked her what had taken place while she had been away, and she told him everything that had transpired. He smiled, then said something under his breath that she couldn’t make out. “Do you know,” he said, “that the man teaching you French was Venture de Paradis, the chief translator for the French Campaign? He is Bonaparte’s personal interpreter.” He became more expansive as they walked through the garden. “He lived his life between Istanbul and Syria, then moved on to Egypt and Marrakech. He speaks Arabic, Persian, and Turkish in addition to his native language, and he was a French interpreter for a long time at the Turkish Embassy. He is an important man indeed, respected and feared by Napoleon himself.” They arrived at their mounts. “Do you know what it means for Napoleon to entrust your teaching of French to a man of such stature?”

Naturally, she knew what it meant for Monsieur Venture de Paradis himself to be teaching her French. She gave a sly smile at knowing just how taken Napoleon was with her.

That evening, the moon was bright and the weather unbearably hot. From time to time, a cool breeze blew. Zeinab’s mother asked the slave woman to set the table for dinner in the courtyard, which she did on a big brass tray upon a central table. Everyone gathered around the table, set richly with birds and meats and the duck soup that was Zeinab’s favorite. She ate with great appetite, which was unusual for her: but her unaccustomed appetite was not due only to the duck soup. The day she had had was enough to give her an appetite, not only for food, but for life. She chattered away to her family about everything that had taken place in euphoric tones bursting with joy, and they listened, enthralled. The only one who plied her with questions was her mother. “Didn’t the woman who took your measurements ask you what you wanted your new dress to look like?”

“I don’t remember hearing her voice. Perhaps she’s dumb?” Zeinab shrugged. “She was quite different from the French teacher. He never stopped talking. And he smiled at me! And he said ‘Bravo’ to me several times!”

In their bedroom, her mother sat on the edge of the bed while Sheikh al-Bakri lay on his back in bed. Suspiciously, she asked him, “What does Bonaparte want with our daughter?” She narrowed her eyes. “What is that invader preparing her for?”

“Fortune,” chuckled al-Bakri, “has smiled upon our daughter.”

“Fortune? What fortune? What ill-luck awaits us with that infidel?”

“An invader,” he mocked, “and an infidel?”

“What else should I call him?”

“I’m tired,” he said, “and not up to discussions right now. You’d best go to sleep.” And with that, he turned his back on her, and a few moments later was snoring loudly. But his wife’s rest was uneasy, plagued with suspicions and doubts, and she could not sleep a wink.

She was not the only one who couldn’t sleep that night. In the next room, Zeinab lay awake as well; but unlike her mother, she could not sleep for joy. By candlelight, she pored over her notebook, dipping the quill into the inkwell and copying out the letters. This was the language that would open closed doors to her—the doors of a new world. A world brighter and more spacious, more beautiful and more wonderful, than anything she had heard of, nor yet imagined, not even in her dreams.

*

At nine every morning, a magnificent carriage crunched over the gravel, its horses beating the ground with their hooves, cutting through the narrow alleyway and raising a cloud of dust in its wake that blocked all sight. It was Bonaparte’s personal carriage, driven by a special coachman, next to whom sat a French guard in a cap with a feather in it that fluttered in the wind, come to pick up a fifteen-year-old girl, a girl with braids that lay over her shoulders and a shy smile set in innocent, childlike features. From there, it took her to Bonaparte’s imperial seat, where she resumed her French lessons with Monsieur de Paradis, the kindly old man who was patient with her to an unimaginable degree. He never begrudged the time it took her to learn to pronounce the sounds and spell the words, patting her gently and kindly on the shoulder, and never tiring of repeating the words over and over again. She could not remember a single time he lost his patience with her.

One day, when her lesson was over, the guard took her, not to the carriage as he did every time, but commanded her to follow him to the room where the seamstresses worked. Could her dreams be coming true? It was all she could think as the seamstress turned her this way and that, adjusting the cut and drape of the dresses over her slim figure, for the design of the gowns seemed to resemble those she had seen on the women at the ball Napoleon had hosted a few weeks ago, the one she had watched from behind the meshrabiyeh, wishing so desperately to be like them, to wear what they wore, and speak their foreign language.

The seamstress folded the dresses and placed them into boxes, then gave them to Zeinab. She looked at her, and for the first time, Zeinab heard her voice. It was dry and hoarse, like the touch of an autumn leaf. “There are accessories to bring out the dresses,” she said, and spent some moments demonstrating how to wear corsets and heels. Then she gestured to the traditional Egyptian crescent-shaped gold necklace at Zeinab’s throat. With some haughtiness, she went on, “This type of jewelry does not suit them. Also, these braids have to go. Please, don’t spoil what I’ve worked so hard to create.” Then she straightened. “The next time you come to the palace, you must wear these clothes.” Then she left Zeinab and disappeared into the bowels of the dressmaking workshop.

Zeinab shook her head: would it kill the woman to smile? Still, she staggered out of the room under a pile of boxes, helped with her burdens by the guard who supervised her while within the palace. They arrived at the carriage that was waiting for her outside, and he placed the boxes into it. They set off for home.

The boxes did not contain dresses only, but the other necessities of smart attire, without which the look would be ruined, as the stick-dry woman had said. There were high-heeled shoes, big hats of different shapes and sizes and colors, and most importantly, the wire crinoline that must be worn under the skirts to give them their shape. Zeinab ran and jumped for joy like a little girl, opening each package, putting on the hats each in turn, wrapping each dress around herself and swaying to the left and right, putting on and taking off the gloves—but she stopped at the high-heeled shoes, looking at them with fear and awe. She had no idea how she could walk in them. She avoided even the high clogs in public bathhouses, made of a broad, high platform of wood to keep women from slipping and falling. How would she manage these thin, too-high heels?

Her father could not wipe the sly smile off his face, while her brothers looked on in astonished curiosity. Only her mother, preoccupied and upset, retreated into a corner of the courtyard. Eager to show off her new dress, Zeinab ran to her. “What do you think, Mother? What do you think?”

“Of what?” her mother said dolefully. “Where do you think you can go, dressed like that?”

Zeinab wasn’t listening. The sound of her happiness drowned out her mother’s sorrow. But the next morning, the answer to her mother’s question became apparent.

*

The streets were bedecked with decorations. The French put up a giant flagpole in the middle of Ezbekiya Lake, hoisting flags and a mock Arc de Triomphe, next to which was a long marquee emblazoned with the words “La Ilaha Illa Allah, Muhammad Rasul Allah”—there is no God but Allah and Muhammad is His prophet—the Islamic declaration of faith. In the center of the square was an obelisk with a pyramid-shaped top, about seventy meters high. Emblazoned on one of its sides were the words, “République Française.” On the other side was “Ousting the Mamluks.”

Three gunshots heralded the start of the celebrations, followed by more pops and bangs. Napoleon Bonaparte himself stood tall among the people to give a speech. His soldiers and officers cheered when he came to the line, “The eyes of the world are upon us.” On that day in particular, it was impossible to believe that these people joking and laughing and celebrating with the Egyptian populace were the French soldiers who had killed and been killed, mere days ago, to take Cairo. French tricornes mingled with Arabian turbans, and snatches of French and Arabic conversation rang out and intermingled. Banqueting tables were laid out, bearing a combination of Egyptian and European dishes. After the great banquet, when everyone had eaten, the horse racing commenced. When evening came, everyone’s eyes were on the sky, where the French had fired several joyous shots and burned gunpowder to create fireworks, lighting up the heavens in an enthralling spectacle.

Zeinab was invited to the private party that Napoleon was giving at his palace for the occasion. The invitation arrived early in the morning with one of his guards, who knocked twice on the door and waited politely until the slave opened it for him. In refined French, he asked her for Mademoiselle Zeinab al-Bakri. The serving girl gawked. He presented the invitation, smiled and left, leaving her still rooted to the spot, staring after him.

Having only understood ‘Zeinab’ out of all he had said, the slave realized that the missive was for her. The message was written in graceful handwriting on expensive paper, and signed by Napoleon Bonaparte. The invitation did not include her father, not even mentioning him, although he had gone to offer his congratulations along with a number of Azharite imams and the members of the Diwan, and several high-ranking Copts and Levantines. Earlier, they had put on their cashmere turbans and taken out their best mounts to listen dutifully to the speech of the French bishop, who had stood under the giant flagpole and sermonized and sought to inspire them with courage, talking at them in French.

At sunset, the celebration for the common people drew to a close, and Napoleon and his retinue made ready for the private party, to which Zeinab had been invited. Sheikh al-Bakri was not upset that the invitation did not include him: he had no objections to his daughter going alone to a party to celebrate with the French community. On the contrary, he was filled with pride that out of all the men and women in all of Egypt, she had been invited.

When evening came, Zeinab prepared herself with the help of Seada, the grooming lady who helped women get ready for special occasions and weddings. She sent Maliha out to fetch her, and in an hour she arrived with a wicker basket containing her supplies: henna powder, rough loofahs, pumice stone, kohl, rouge, powder, musk and ambergris, and combs and hairpins. Zeinab took her straight to her room: there was no need to bathe or depilate her, for she had had her slave already do it—the woman had been surprised to be asked to remove the hair on Zeinab’s arms and legs, for girls never did that until the Henna Night, the night before their wedding day. Zeinab had made the excuse that her body hair was so thick that the new clothes would reveal it, making her look ugly, whereas she wanted to be at her prettiest and every bit the equal of the foreign women.

It was not only the serving woman who was astonished at Zeinab’s request; Seada the grooming expert also found it odd that Zeinab wanted her to pluck her eyebrows. No virgin girl had ever dared make such a request: plucking was reserved solely for married women. Still, she pulled her tweezers out of her basket and started to pluck the girl’s brows, chattering incessantly. Zeinab laughed at her way of pronouncing her z as an s. “The people,” Seada said, “are growing resentful at the Western laws that the Franks are imposing.” She plucked a few stray hairs from the center. “Every day they issue a decree stranger than the one before it. Isn’t it enough for them that we have to sweep the streets every day and splash them with water and light the oil lamps over the gates of our houses? The worst of it is these papers they’re having us make out when each new child is born or when someone dies. Even traveling abroad, you have to get a paper for that too, if you can believe it! The newest fad is to take down a list of the people living in every house, and their names and ages to boot. And they’ve imposed strict penalties against mocking any French soldiers wounded or vanquished in any battle. Oh, and get this—they even ordered us to hang out our washing in the sun and air out our houses well, so as to stop the spread of the plague. . . .”

“Seada, enough of that. This isn’t the time for this kind of talk. I’m getting ready to go to dinner in honor of the emperor, and you’re talking about laws and taxes and plagues? What do I care about that?”

“True,” Seada said bitterly, “what do you care?”

She looked like a princess, a creature neither of the East nor of the West. Her crowning glory, her hair, she had plaited into two braids wrapped around her head and then concealed beneath a large hat decorated with fur and feathers. Everyone in the household came to look at her: her father, her mother, her brothers of all ages, and all the slaves and servants. They all looked at her and wondered, “Who is she?”

Her father approached her, saying, “Subhan Allah, you are so lovely! What a change in you!” Meanwhile, her mother stood observing her, eyes full of sorrow and anxiety, saying nothing. But when Zeinab was just about to go out, she approached her and took her by the hand, and whispered in her ear.

“Safeguard your honor. Don’t let anyone touch you or approach you. Don’t let anyone go too far when they speak to you. Those people are devils incarnate. Don’t forget that Bonaparte, for all he seems gentle, gives the order to have four or five people beheaded every single day, not to mention the ones he has thrown into the Citadel dungeons, never to be heard from again. Are they alive, or did he get rid of them and throw them in the river? Look how many bodies come floating up to the surface in burlap sacks day after day. Don’t trust him. Beware of him.”

Then she put her hand on Zeinab’s head and murmured blessings and recited verses from the Qur’an.

Zeinab listened to her mother’s advice and nodded in silent acquiescence. She knew that any further discussions with her mother would lead to a fight, and she wanted nothing to ruin her happiness this evening.

Bonaparte’s carriage was due any minute, coming especially to take her to the ball. As usual, the coachman drove at top speed, heedless of the whirlwinds of dust his horses kicked up behind him, rattling to a stop outside the door. He rang the bell of his carriage to let Zeinab know he had arrived. That evening, Zeinab was the center of attention not only for her family, but for everyone in their street, if not their entire neighborhood. All the men and boys thronged the street to see her, and the women and girls clustered behind the meshrabiyeh to watch her enviously, one thing on their lips: “Look at Zeinab, Sheikh al-Bakri’s daughter! Look what she’s done to herself!”

“How can her father allow her to go out with her face unveiled, wearing see-through clothing?” they whispered.

Zeinab had always worn a long, wide veil that fell to the ground and covered her face; she did not catch anyone’s eye, concealed as she was beneath mountains of fabric. But the women of the neighborhood always made much of her beauty, and it was every young man’s dream to see the face of Zeinab, Sheikh al-Bakri’s daughter. Today, the dream of the men and boys of the neighborhood had come true, and here Zeinab was, her face on display. The women with their matronly busts under their black gallabiyas and their veils covering their heads stood whispering, some twisting their lips in disapproval and others beating their breasts in shock and dismay. But who could dare to stand in the way of Sheikh al-Bakri’s daughter on her way to a ball given by Bonaparte himself on the French day of celebration?

The carriage arrived. A few meters away, Napoleon’s palace was bathed in light, and the sound of music wafted outside. With a nervous tread, Zeinab walked down the path that led into the palace. She remembered her mother’s words about those who had been drowned, and suddenly her ears were filled with the screams of the people thrown into the darkened dungeons. Louder and louder, she heard the murmurs of those trying to get out of the sacks before they were thrown in the river, and she saw the heads of the traitors mounted day after day on pikes at the Zuweila Gate to the city. Fear and apprehension coursed through her; she tripped on a marble step and would have fallen, if a strong hand from behind had not caught her. “Thank you,” she said, looking back to offer her gratitude to whoever it was. She recognized him. When the French officer had barred her way, this was the man who had stood up to him, rebuked him, and cleared the path for her to pass. Again he had saved her, as though it was her fate to be rescued by him.

He was handsome, that was undeniable. It was hard to tell his age or origins: he seemed to be in his early thirties, a Frenchman perhaps, or an Italian, or a Greek. “I would have fallen for sure,” she smiled, feeling proud at her command of French and the fact that she could communicate in that language. Where would she have been, she thought, if she couldn’t speak French? What language would she have used to thank him? How grateful she felt to Monsieur Paradis, her tutor! If it wasn’t for him, she would never have managed it.

He gave her a friendly smile, then went on his way. The major-domo met her and looked at her for a moment; then he bowed. “Bonsoir, Mademoiselle.”

It was like stepping into another world, a world she had never thought to experience or be a part of. All the men were in tuxedos, and as for the women, it was a positive competition of elegance and beauty. Some had come with the Campaign, and some were part of the larger French community already living in Cairo and Alexandria, which had incidentally been the reason for the campaign on Egypt—if the ruler Murad Bey had not subjected that community to great injustices, their mayor would not have written a letter of complaint to the French Consul, who in turn wrote to Napoleon urging him to send a campaign to keep the Mamluks in line and tempting him to come and invade these bountiful lands.

Turks, Armenians, Levantines, everyone who was anyone, merchants and consuls, Zeinab could see them all here at the celebration. Streamers decorated the walls and hung down from the ceilings, an orchestra played Western music, and servants moved around bearing trays of crystal glasses filled with liquor. For a moment, she felt lost among this great crowd: she knew no one, and no one knew her, and she did not know who she was. She was no longer the simple Egyptian girl with skin the color of Nile silt, and yet she bore no resemblance to the French women, but stopped somewhere in the middle, where it was difficult to take a step forward or backward. In such a position, questions start to come up: Who am I? What do I want? Who brought me here? Do I really belong here? Although she finally had the look she dreamed of, and acquired a good deal of French which allowed her to move forward in this new world she had entered, she felt no joy or pride. Something was missing. Perhaps she had lost her own self.

Bonaparte was standing among a group of commanders of his army, in full regalia as he was most of the time, never seeming to take off his uniform. The major-domo led her to him so that she might congratulate him on the anniversary of victory. Reluctantly, she followed the man, who stopped directly in front of Bonaparte. The general saw her and nodded for her to introduce herself. She managed to choke out in low tones, “Zeinab al-Bakri.”

Bonaparte’s eyes raked over her in a flash, astonishment filling his face. Then he burst into uproarious laughter. “Is it possible? Look at you! You’re completely changed!” He laughed again, as the men around him fixed her with curious glances. On his right was Caffarelli, one of the leaders of the Campaign, who was also known as a painter. Napoleon turned to him. “Look at this beauty, Caffarelli! What would you think about painting her?”

Caffarelli laughed, rocking on his wooden leg, but his features did not soften. “It would be an honor for me to paint such loveliness,” he said, “but I only paint the victories of Napoleon Bonaparte.” He raised his glass to the general, adding, “I am no longer entranced by women’s faces. But wait!” He pointed at someone else standing nearby. In a moment, the man Caffarelli had pointed to came over. Her heart filled with gladness to recognize her savior of earlier. He bowed to Napoleon and congratulated him. “This is Alton. He is an accomplished artist. He came with the rest of the Campaign, and his job is to document important matters. There is nothing more important, I believe, than painting such authentic Egyptian features.”

Napoleon nodded approval. Caffarelli touched her cheek with his fingertips. “What do you think of this face? Isn’t it worth painting? Don’t these features have the right to be documented in a painting that will survive across generations, across time, a constant reminder that such loveliness once existed?”

Alton looked directly into Zeinab’s eyes. Her heart beat faster and she felt herself flush. He was scrutinizing her, taking in every detail, as though weighing the man’s words. Finally he said quietly, “Definitely this face is worth painting. The moment I set eyes on her, I was certain that she was not French, despite her clothing and her language. Her deeply Oriental features proclaim her true identity.” He looked at her directly again and she felt as though his gaze pierced through to her core. More lightly, he said, “I think you would be lovelier in your Oriental clothing.”

Napoleon smiled at Alton, downing his glass in one gulp, then commanded the major-domo to take Zeinab to Madame Pauline and her lady friends. He took her to a group of women standing in a corner of the atrium, approaching one of them and whispering in her ear. The woman smiled a welcome at Zeinab, taking her in from head to toe. And with that, she stepped into the closed circle of the aristocracy, and she might as well not have been there. For more than half an hour, she said not a word. She made no attempt to cut into their conversation, for what would she have had to say? The women were all talking about the deplorable state of the country, the even more deplorable state of the Egyptians, the unbearable heat, the mosquitoes and flies and insects everywhere, the dirty streets, the disgusting odors. “If Bonaparte had not issued his edict,” one woman said, “I do believe we would all have suffocated from the stench!”

Another woman spoke up in a high, squeaky voice. She wore a puffy dress and a hat adorned with several feathers, each a different color, giving her the air of a parrot. “The Egyptians care for nothing but sleeping, eating, and reproducing,” she exclaimed. The women tittered along with her. A waiter passed with a tray and they plucked glasses of wine and liquor from it. He offered it to Zeinab and she hesitated: should she reach for a glass or not? But if she did not, she would be the laughingstock of these brainless women. Besides, hadn’t she dreamed of being like the women at these parties? To dress like them, to dance like them, and even to drink like them? And now that her dream had come true, what was keeping her from reaching out and taking a glass?

She took a sip; it was sharp and bitter. She was forced to swallow it, but realized she wouldn’t be able to drink any more, and pretended to be drinking and enjoying it. The women’s talk had turned to another topic: Paris and the gossip of those who lived there. She lost interest and stood there, hardly listening to the conversation about people of whom she knew nothing; what did she care about the doings of Mademoiselle So-and-So and the misadventures of Madame Such-and-Such?

Looking around, she caught a glimpse of Napoleon deep in conversation with Muallim Yaacoub, the leader of the Coptic community. So the rumors must be true: Yaacoub was completely on the side of Napoleon, he and the Copts were at his command, and he had offered the services of several young Copts in the service of the Campaign!

She took a few steps away from the women; nobody noticed her departure. She was of no consequence to them. Alton came up to her, took her by the hand, and led her into the courtyard in the rear.

The courtyard was redolent with privet and night-blooming jasmine, the perfume blowing around with the cool summer breeze. They stopped under a large oak three that hid them from prying eyes. “But tell me,” he said, “what’s your name?”

“Zeinab.”

“Zeinab,” he repeated. “Zeinab. . . . What does it mean?”

She did not know what her name meant. She shrugged carelessly. “I don’t know. What’s yours?”

“Alton.” He paused, then answered a slew of questions she had never asked. “I’m twenty-eight. I studied painting at art school in Paris. I came with the Campaign to draw and paint everything strange and unusual that my eyes fell upon, and you are the most beautiful, exotic thing I have ever seen.” The French she had learned was insufficient to keep up with this gentleman who spoke in a rush, so she tried to pick up a word here and there to understand what he was saying. “But forgive my asking: why are you here?”

She repeated the question to herself. “Why am I here. . . . ?” Then she remembered. “Because Napoleon wants it.”

He scoffed, thinking, What does Napoleon see in this innocent little girl, who knows nothing whatsoever of life? She has none of the skills of any of Napoleon’s lovers; besides, he prefers women who are older than him. Or maybe he likes that she’s different.

The major-domo announced that dinner was served. Bonaparte led the way, sitting at the head of the long table that seemed endless. He gave a short speech of welcome to the guests and raised his glass, “To France!”

She sat next to Alton; he was her lodestar in this strange place, and without him she would have remained lost. Having him with her made her feel safe. She marveled at the table setting, the likes of which she had never seen before. At every seat was a plate, knives and forks of pure silver, and a white napkin with embroidered edges.

The waiters began to serve the meal. She saw everyone unrolling their napkins, so she followed suit. After the soup, the waiters removed the plates while others replaced them with another dish; and so it went, as waiter followed waiter, and course followed course. She was overcome with nervousness, as she had never used silverware before, but with a glance at how the people around her held their forks and knives, and since she was intelligent, she managed to pick

it up.

As she sat at the long table, she thought of their round table back at home, around which all the family gathered, and how they only used their hands to eat—hands were good enough for everything, after all. Here, there was no conversation while eating, no sound but the clink of fork and knife, one ate with one’s mouth closed, and one’s teeth performed their function slowly, not like the threshing machines that her family’s jaws became as they chewed their food. Her family loved to talk with their mouths full, as though there were no better time for conversation.

The meal ended when the final dessert dish was served. It was an odd kind of sweetmeat, shapeless in form and texture, but it was delicious, so she demolished it to the last spoonful.

Napoleon rose, announcing the conclusion of the banquet, and everyone followed suit. The musicians started playing again, and the glasses started making the rounds once more. Someone came up to Alton and asked for a word with him; he excused himself from her and left, promising not to be long.

She had only been standing alone for a few moments when Napoleon’s private secretary came to her and asked her to follow him. She reluctantly followed him, trembling like a leaf in the wind. What fate awaited her? What did this man have in store? Her mother’s words rang in her ears: “Don’t trust him. Beware of him.” Her hand crept up to her neck in terror, but she shook her head sternly, dismissing the idea. Certainly Napoleon would not harm her. Why should he? If he had wanted to hurt her, why did he have her taught French? Perhaps to hear her beg for her life in a language he could understand?

She ascended the marble staircase and walked down a long passageway. It was carpeted with a long, red rug with an Oriental pattern, and on either side of her, the walls were lined with paintings. There were small side tables bearing statues of genuine Limoges porcelain. She walked slowly, hands lifting the hem of her dress. They reached a room at the end of the passage. The man stopped and knocked at the door. A male voice came from inside: “Entrez!” The major-domo left her to her fate, but not before he had looked long and searchingly at her with a question in his mind: What does the general want with this girl?

She found herself stepping into a strange room, a mix of East and West so complete that it would have been hard to tell where one was on this great Earth. The rug on the floor had an Oriental pattern; the bed was in the French style; the lantern in the ceiling was arabesque; the vases were Limoges with a Romeo and Juliet pattern. Not so strange, after all, for a man who would appoint himself Emperor of the East and West, to bring them together in this tiny corner of the world. Had he not given a speech to the Muslims on the day of the Prophet’s birthday, handed out gifts and largesse, and worn a turban and a caftan? Today, he was celebrating the anniversary of the French Republic, raising a glass and drinking wine.

He stood with his back to her, looking out of the window of the palace, legs slightly apart. At last he had set his hat aside: his thinning hair was smooth and chestnut-colored. He left her standing in the sea of her shyness for a few moments, and she said not a word. Then he turned to her. His hair was creeping down over his forehead and partly covering his eyes. There was no trace of the renowned cruelty in his features, nor the strength and courage he was known for. He had the face of a shy and innocent boy. Could appearances truly be this deceiving?

He approached her and took her hat off, tossing it onto the bed. Then he whispered her name into her ear. “Zeinab. . . .”

She had never heard her name said so sweetly before. Could the man saying it in such tones be Napoleon, the great warrior? Slowly, he ran the tips of his fingers up and down her cheek and neck, a pleasant sensation. The scent of musk and ambergris still clung to her from where the slave girl had added it to her bathwater that morning and burned it in incense, and now it hung in the air between them.

He came closer and put his nose to her neck, inhaling her scent in ecstasy. “How wonderful you smell,” he murmured, “how lovely you are!”

He took her by the hand and gently led her to sit next to him on the bed. She found herself sitting close to his medals, proudly hanging from his uniform jacket. Conflicting feelings rushed through her: pride and guilt, confidence and unease, panic that stopped her breath at what was about to happen, like a tiny fish in the presence of the vastness of the sea.

The room was lit by candlelight. The overpowering scent of his masculine perfume filled her nostrils, and he was only a few breaths away. He took off her hoop earrings, opened her small hand and placed them into it. Then he began to undo her braids one by one, lock after lock of hair coming free, and with every lock, he plucked out the cloves that Maliha had braided into her hair. He pursued this task with great care and patience, making sure not to hurt her when he separated the tangles in her hair. Silence weighted the room down, making her feel as though time was passing impossibly slowly, as if it had stopped. One question filled her mind: What was to come after undoing the braids?

Finally, her hair hung free, cascading like a waterfall down her back. He gently stroked it, then said, “Go now.”

Had the greatest and most powerful man in the world truly been undoing her braids with matchless care and patience, like a man preparing his lover for a night of love, taking off her earrings, inhaling the perfume of her body, loosening her hair? How much time had he taken, undoing her braids? Nearly an hour. He had not spoken a word in that time. Then to ask her to leave?

She stepped outside the room, sighing with relief, still flustered and shrouded in fear. Down the long corridor she went, trying to gather up her loose hair and twist it into a bun at the top of her head, jamming the hat down on top of it to hide it. It was no use, though; her hair slipped out, long locks of it straying free. She hurried down the stairs, although she was aware that no one had noticed her disappearance, just as no one had noticed her presence. They were dancing joyously, well into their wine by now.

She had been wrong. One person had noticed her disappearance, and after searching for her everywhere, had convinced himself that she must have had to leave in a hurry without saying goodbye. All of a sudden, as he lifted his glass to his lips, he caught sight of her coming down the stairs, flustered and uneasy. Their eyes met; she saw a question in his eyes and a cynical smile. For the second time, she slipped and would have fallen, if Bonaparte’s secretary had not caught her—he had been waiting at the bottom of the stairs until his employer had finished his rites of passion with her. He caught her and propelled her to the carriage that was waiting outside to take her home.

The carriage rattled all the way, scraping against the walls of the ancient houses on both sides of the narrow street. The moon disappeared behind a cloud in the black velvet sky. August was hot and humid, and the darkened streets were swallowed up in mist, but for the light of an oil lamp here and there. Everyone was deep asleep at such a late hour of the night. Only this girl of fifteen was awake, asking herself all the way home: Was what happened real, or was it a flight of fancy? Did I truly sit close to Napoleon? Did he take off my earrings and undo my braids? Did he kiss my neck and inhale my scent? And the handsome artist, did I truly meet him? Was what happened real?

A few days after that celebration, the stiff festoons put up for the celebrations were shattered by a gale, leading people to be optimistic that this heralded the end of the rule of the French.