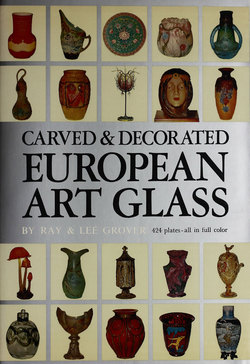

Читать книгу Carved & Decorated European Art Glass - Ray Grover - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеENGLAND

CERTAIN VALUES ARE IMPORTANT to the identification of art glass. Engraved and impressed signatures, rather than easily transferred or washed off paper labels, appear on occasion. Original documents of registration with the London Patent Office are still available, upon application with suitable fee. Private collections in the original glass creator's families and the collections of the factories themselves are of considerable importance, the major ones still being in active operation today. These would be Thomas Webb and Sons, and Stevens and Williams, both at their original sites in the Stourbridge area. Bearing in mind that this great art glass work continued into the twentieth century, many of the most important artists living themselves through the first quarter of that period, we may still find today men who were personally acquainted with these artists during the latter part of their lives. We personally met several men in charge of the work at the above plants who in their early formative years had studied with these same famous art glass men. Hence on the basis of such an accumulation of evidence and personal knowledge in our interviews and photography, a remarkable consistency appeared in the answers we received to our many questions of origin and techniques. With no one did there ever appear any desire to appropriate, in retrospect, any credit for work done' elsewhere. On the contrary there was never any hesitancy to definitely point out the origin of the correct factories and artists.

In the Stourbridge area, several hours drive by automobile on the throughway from London, there are four important and worthwhile sources to visit. Should you be interested in such a trip it cannot be too highly stressed that you make sure that the places are open, as it requires a personal guide in each museum. There is no lack of cooperation, but rather the lack of readily available personal help. Lights have to be turned on, and most important, the visitor is never left alone, other than for casual inspection. Local accommodations in the Stourbridge area, contrary to that found elsewheres in England, are quite minimal, so a car is necessary.

Of least importance is the collection at the factory of Thomas Webb and Sons, as well as the collection of Webb and Corbett across the street, which has no colored glass in their group. Brierley Hill Library and Stevens and Williams Ltd. being only two blocks apart should be visited together, and are of equal interest. There is practically no duplication in these two important places, and neither one should be overlooked. Unquestionably the most important museum collection in the entire Stourbridge area is in the Stourbridge Council House, situated in a park, and very easily found. In this municipally owned collection a few hundred pieces of glass are on permanent exhibit. John Northwood II, who retired from Stevens and Williams in 1947, several years later transferred the major part of his glass collection to the Council House. This Northwood bequest joined that of the Richardson family, with all pieces being carefully catalogued and documented. There are of course, many other fine examples from other sources, every one being identified beyond question. When first seen, many surprises are in store, for this whole group goes back to the 1850's, and what might originally have been attributed to not only a later, and almost present period of manufacture, is frequently the earliest work. The few pieces on public display in the museums in London, in toto, would not fill even one case in this Council House. This is not to suggest that the major museums in London do not have the pieces numerically, but, in matter of fact, they are tucked away in the museum reserves, and not available to the general public. Strangely enough only mediocre examples were on display in the hub of the English empire, with far greater and important work in storage. To any glass collector the Stourbridge visit is most worthwhile.

While in our preceding book Art Glass Nouveau we had a small section on English Art Glass, we decided it to be an important contribution to cover the examples in the Stourbridge museum collections as it is realistically highly unlikely that too many American collectors will have the opportunity to make this trip.

* * * * *

Cameo

English cameo carving, covering a period of the last quarter of the 19th century and running through the 1920's, spans a relatively short period in the history of art. During this brief period, however, cameo glass work developed and reached a peak never achieved prior to this era. There is little reason to believe that the future will ever afford sufficient opportunity for artist workmen to acquire the training necessary for the requisite proficiency demanded by this art. As will be seen in the colored photographs to follow, there is no substitute for artistic ability in the design of the human figure. There is also no substitute for the necessary ability of this same artist as an accomplished glass blower, and finally, we must continue to have this same man capable of carving the scenes he desires. It should be pointed out that many of the cameos required several years of devotion. Plate 47 is an unfortunate example. This plaque "Aphrodite," some 15" in diameter was certainly a labor of love for four years. At this point due to an unfortunate accident, the piece was broken. Quite obviously the artist John Northwood II was not financially embarrassed, but when the realization comes that these particular works of glass were not produced for monetary gain, it is then recognized that the artist-workman must not be dependent upon his craftmanship alone. This piece has been retained by the Stevens and Williams Ltd. in their private glass museum, which is not large, but impressive.

Cameo glass work is the result of two or more layers of glass having been laminated together. By means of acid and hand-tool carving, the final pattern on the outer surface is left in high relief by removing the surrounding area. When the different layers of glass are of contrasting colors, we have a generally roughed-in design. Plate 60 is a fine example of the roughed-in sketching and the subsequent protection of the surface which will be left uncut. The brownish-black painted sketch consists of bituminous or other acid-resisting substance. This handled vase is ready for dipping in the acid bath, during which operation the white part of the vase will gradually be eaten away by the corrosive action of the acid. The high relief of the pattern is dependent on the length of time the piece is left in the acid bath. This background surface is also known as the "ground." When a piece consists of more than two layers, one layer of background or "ground" glass will then be removed. A new perspective with depth, created by shadowed layers of glass, is developed by partially removing with hand and wheel tools, in an engraving manner, sections of the design itself.

Plate 52, "The American Girl" by George Woodall, expresses this new concept most forcefully. The portrait was originally a solid white, after the surrounding acid cut-back process. By means of grinding tools, Woodall then proceeded to cut into the white section until the dark background began to show through. Shadows were thus created until life likeness appeared. In other words, what Woodall did was to paint a picture by removal of glass, rather than with an addition of oil or water color and brush. Quite obviously these workmen must have been accomplished painters in their own right.

The Stourbridge area of England has possibly a minimum diameter of five miles. During the first part of the 17th century Huguenot glass-workers from France fled to England and settled in the Stourbridge area because of the ready availability of the requisite raw materials for their trade, in particular coal and fireclay for the construction of furnaces. There are today several firebrick manufacturers active in the area. Documented histories of these original families are still available, with similar or slightly altered names.

Today, driving north from the center of the town of Stourbridge, in Staffordshire, some one-half mile on the left is the glass factory of Webb and Corbett, specializing at the present time in crystal. Diagonally across the street lies the property of Thomas Webb and Sons. Located there is the head office and plant which is still operating. Here crystal is also produced, but in limited quantity only at the moment, as a change of ownership has recently taken place. About a mile further east is the imposing works of Stevens and Williams, better known today as the Royal Brierley Crystal of England, a division of Stevens and Williams, Ltd. Smaller operating glassworks are also in the surrounding areas. Upon realization of this geographic relationship, it is easily recognized that most artist workmen would not necessarily spend forty or fifty productive years of their life in one single factory. The individual designer trademarks of these men were not left behind when they transferred their allegiance from one factory to another, as these marks were their own emotional makeup. We should, therefore, not be too critical of a wrong attribution on an unsigned piece as to whether it had its origin in either Webb or Stevens and Williams. Only one criterion is important, and that is the finished quality of the piece itself. Should the handmark or signature of a Woodall, Locke, or Northwood also appear on the piece, a considerable value would, of course, be added. A company mark has relatively small additional value in view of the fact that it is either English cameo or not, and if it is English, the origin was in this Stourbridge area. It is the artistic accomplishment that is important. Strangely enough, neither the personal productions of Joseph Locke with the New England Glass Co. and, subsequently, The Libbey Glass Co., nor those of Frederick Carder, co-founder of The Steuben Glass Co., would ever be mistaken for the work they did in England prior to their emigration to the United States. It must also not be overlooked that these glassmen, as their period of retirement occurred, normally would continue to use factory blanks in their own home workshops.

A salient feature that strikes one quite forcibly in digging into the personal history of these artist workmen, was their close relationship to each other. There existed in the Stourbridge area a very fine and well-recognized school of art. It became a common practice for the greatest of the top group of glassmen to attend this school faithfully, from their early school years to the latter part of their lives. This particular art training was pursued after their factory work was over, several times a week. Not one of the great artists in Stourbridge was an exception to this rule, and the evident devotion to their trade is all too evident in the high standards of their general production, to say nothing of their individual pieces.

Glass factory owners were not only employers, but also patrons for individual productions on the part of their men. This in itself accounts for the positive origin of the many unsigned pieces. When you walk into the factory museum of Stevens and Williams today, only open to the general public with prior arrangements, and you see several cases of art glass made for the factory by individually recorded workers at the time of manufacture, any question of origin ceases. It must be recalled that these particular works were never offered for sale, nor quite obviously are they today. Stevens and Williams has a recorded history in glass production of one hundred and forty years.

* * * * *

Lechevrel