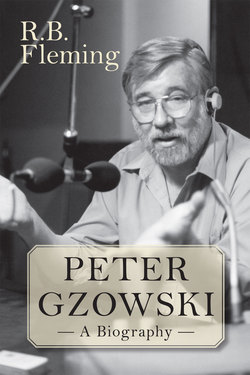

Читать книгу Peter Gzowski - R.B. Fleming - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление— 2 — “Don’t Try to Be Something That You’re Not,” 1950–1956

Though acne neither kills nor cripples, it can leave mental and physical scars for life.

— Maclean’s, June 17, 1961

It was an ink fight, Peter claimed, that made him feel at home at Ridley College, a private boys’ school in St. Catharines, Ontario. During the early 1950s, ballpoint pens were just coming into use.1 More widely used for letters and note-taking was the fountain pen, which sucked up ink from small glass bottles set into specially designed holes on each student’s desk. When pumped full, these pens could be made to gush ink over a considerable distance. One evening during a study period, Mr. Cockburn, the master in charge, stepped out for a couple of minutes. Shiggy Banks launched a stream of ink at Jimmy Conklin. Sitting midway between the two, Peter was sprayed by tiny drops of blue ink. Soon the room erupted into a general melee. In his introduction to A Sense of Tradition, a book celebrating the centenary of Ridley College, Peter was at his best in re-creating the battle, complete with literary and cinematic allusions: “By now, hostilities are spreading. Incidental skirmishes break out on the perimeter. Pens dip to inkwells. Pump, load, slurp, fire. No one is safe. The air is wet with ink. Faces, white shirts, brown desks … everything is spattered with blue Rorschach stains and arpeggios of polka dots.” It was a slugfest straight out of a Roy Rogers movie, imagined Peter. “And I am in the thick of it,” he continued, “happily splashing, happily splashed. I drench Freddy Lapp. Harry Malcolmson drenches me. Norrie Walker hits a double — Bob Broad and John Girvin with the same roundhouse swing. Broad gets me. I go for Walker. By the time that Mr. Cockburn returns, the damage is done. We are the sons of Harlech, drenched in woad.” After cleanup the boys returned to their rooms. Finally, Peter felt that he was one of the boys.

Like the story of skating endlessly over fields of ice, or the tale of Peter’s scoring the winning goal in the seventh game of the Stanley Cup, the ink fight owes much to Peter’s imagination. Its rise and fall, its suspense, climax, and denouement are the characteristics of a good short story. Today Norris Walker, who scored that double, has no recollection of the incident. Others have only vague memories, some of them no doubt created by Peter’s account in Sense of Tradition. In his fertile imagination, Peter converted the rudiments of a fight into a story whose theme is the quest to belong. Ink and battles were fitting metaphors for Peter. Throughout his working life he created articles and stories with ink, he fought battles with ink, and it is in ink that he has left a legacy in articles, books, letters, and the scripts of his radio and television shows.

According to Peter, the road to this private boys’ school in St. Catharines was paved with loneliness and failure. Christmas 1949 wasn’t a happy time for the fifteen-year-old. The results of his Christmas exams at Galt Collegiate, he claimed, were disastrous. During the autumn of 1949, he had spent too much time sipping lemon Coke at Moffat’s or “trying to make a pink ball” at Nick’s. Peter’s version of his problems bears a striking resemblance to the story told by his favourite fictional hero, Holden Caulfield. “I wasn’t supposed to come back after Christmas vacation,” Caulfield tells readers of The Catcher in the Rye, “on account of I was flunking four subjects and not applying myself and all.”2 On Boxing Day 1949, Peter headed for Toronto. There are, of course, several versions of the event, including one told by Peter, that, like Holden Caulfield, he ran away from home, his belongings in a bandana.3 More likely, he was driven to Toronto, perhaps by his mother and stepfather. He often visited his grandparents and his father on weekends. Soon the Gzowskis made arrangements to send the boy to a private school where he might improve with stronger discipline. No doubt they talked it over with his mother and stepfather. It was Peter’s father, Harold, who made arrangements with J.R. Hamilton, the headmaster at Ridley.

The college had long Gzowski connections. In the late 1880s, Sir Casimir Gzowski had joined with other wealthy Torontonians to buy an old sanitarium called Springbank in St. Catharines. It became the college’s first building and was used until it was destroyed by fire in 1903. Two of Peter’s great-uncles had been among the first boarders at Ridley when it opened in September 1889. Peter’s father had also enrolled at the college midway through high school in September 1927 at age sixteen.

The Gzowskis bought Peter appropriate Ridley attire — grey flannel slacks, white shirts, and a blue blazer. It was Harold Gzowski who suggested that Peter revert to “Gzowski.” His delighted grandmother sewed tags bearing the name peter john gzowski into his new clothing. Shortly after New Year’s Day, Harold borrowed the Colonel’s Morris Minor to drive Peter to St. Catharines along a snowy Queen Elizabeth Way (QEW). Peter always recalled passing the stone lion west of Toronto, unveiled in 1939 by Queen Elizabeth, consort of King George VI, as part of the official opening ceremonies of the QEW.4

Soon after arriving at the lovely campus, whose mix of Queen Anne, early Georgian, and perpendicular Gothic emulated Eton and other private boys’ schools in Great Britain, “Peter John Gzowski” signed the student registry. He was number 3084, which meant that he was the 3,084th student to register at the college since its founding. Although “Brown” was banished from his name, there is a Brown family story that Reg Brown helped to pay for Peter’s education, a story with credibility, given the pinched financial circumstances of the Gzowskis. In his memoirs and his introduction to A Sense of Tradition, both published in 1988, Peter paints a picture of a bewildered, lonely boy of fifteen surrounded by strangers already familiar with Ridley routines and regulations and already adept at “swapping lies about life at home.” As boys rushed back to their dorms after being dropped off by parents, Peter “stood bewildered in the dark hall of Dean’s House,” which was the college’s oldest surviving residence, opened in 1909. The other residents knew not only one another’s names but also nicknames, proof that they belonged, and that he did not.

Peter was exaggerating his loneliness, for he really hadn’t been dropped into a completely alien environment. He already knew Jim Chaplin, who had been the captain of the Galt Collegiate basketball team, whose members, including Peter, had played at Ridley. Ten years later, in an article in Maclean’s on April 22, 1961, Peter admitted that, even before he arrived at Ridley, he already knew several of the boys there.

Understandably, Ridley rituals were new to Peter, from Latin grace to “houses” without kitchens, as well as chapel, caning, and “masters,” who he quickly learned to call “sir.” He soon realized that he was living not far from battle sites of the War of 1812. He could walk the route of Laura Secord when she warned the British officers and Canadian militia that the Americans were coming.5

At Galt Collegiate, Peter had “wriggled out of Latin,” but at Ridley he was “grinding out” his Latin verbs. Master J.F. Pringle, who taught English literature and composition, kept Peter in line. A wounded veteran of the Great War, Pringle was “occasionally morose,” Peter told Professionally Speaking in 1998, “but also very sharp and quite a pleasure to be around.” In both his memoirs and in Professionally Speaking, Peter noted that Pringle inspired him “to write clearly and well.” In fact, Peter was “something of a star” in Pringle’s composition class, except on one occasion when Peter wrote “a stream of consciousness piece.” Pringle “kicked the living Jesus out of it” by making “caustic comments” and giving Peter a failing grade. “What he meant to me,” Peter concluded, “was don’t be pretentious. Don’t try to be something that you’re not.”6 Pringle was no doubt vexed at Peter when the English teacher read a poem that alluded to Jesus Christ, and Peter asked if this wasn’t the same J. Christ of New Testament fame. One of his classmates remembered that Peter asked the question with a slight stammer, which later, on radio, became one of his trademarks.

Peter was a great disappointment to the choirmaster, who assumed that the son would have inherited his father’s melodious singing voice. “Poor Sid Bett,” Peter recalled. “It was as if Howie Morenz Junior had showed up at hockey camp and couldn’t skate.” Although off-key, Peter loved to sing hymns — his favourite was “Jerusalem” by William Blake. He was also a disappointment to his French master, for he was a year behind in French and never did catch up.

For anything not terribly important like shining shoes and knotting ties, he found ways to fake it. He quickly learned “where to slip down the Hog’s Back for a butt before dinner.” Peter also smoked in the communal showers, where headmasters were unlikely to patrol and where the smoke was camouflaged by mist. He was caught at least once and was strapped by a member of the staff. Within the first six weeks, Peter had served an hour’s detention for saucing a duty boy. He wrote home with the latest hockey scores and with a request for more money to buy things at the tuck shop. Peter skated on the Ridley rink, played squash, and lay awake at night “thinking of the girls I left behind.”

Probably for the first time, Peter met an African American, a boy called E. Abelard Shaw. In 1961, Peter wrote about Shaw in Maclean’s in an article called “My First Negro.” “His features were Negroid all right,” Peter wrote. “He had tight curly hair and a wide, flat nose and full lips that were almost always curved in an enigmatic smile.” In the article, Peter called him Fuzzy-Wuzzy, which is what Rudyard Kipling called Sudanese warriors, not as a compliment, in a poem of the same name. The son of a dentist from Brooklyn, New York, Shaw was admitted to Ridley in spite of an unofficial colour ban. He was an outsider for other reasons: he didn’t smoke, he didn’t play pinball, and he suffered from body odour, as Peter mentioned twice in the article.

Worse, Shaw refused to take part in the Battle of Ridley. “He even kept his inkwell covered so that no one else could fill up at his desk,” Peter wrote in the Maclean’s article. And when the master returned to find the inky mess, Shaw even announced that he hadn’t participated. In the Maclean’s article, Peter’s discomfort is palpable as he recalled his view of Shaw during the early 1950s, especially in a sentence like “I was no more convinced that Shaw wasn’t fit to be my friend than I would have been if he wore crutches.” Peter usually wrote in a much clearer, simpler style. Two negatives and the conditional tense of the verb make for a rather convoluted, worried sentence.

During the late 1980s, when Peter came to write his account of the ink fight in A Sense of Tradition, Shaw had vanished completely from the narrative. Perhaps he didn’t fit neatly enough into the theme of belonging. While Peter would eventually become one of the gang, Shaw was never completely accepted, even when he lost a heavyweight boxing tournament and was awarded a trophy for trying.

Peter had the good fortune that his roommate was John Girvin, who had also transferred to Ridley in early January 1950. At first neither boy wanted to be at Ridley, but they soon adjusted. Girvin was not only an excellent scholar but also a fine athlete. While never as skilled as Girvin, Peter loved sports. In the pages of Acta Ridleiana, one glimpses Peter in the various stages of his two and a half years at Ridley. Soon after arriving, he joined the basketball team. In a team photograph published in Acta in March 1950, Peter stands in the back row, tall and gangly, looking a bit lost, as if he hasn’t quite settled in to Ridley routines. His face shows a touch of acne. He is one of the tallest on the team. A year later, in March 1951, the basketball photograph shows a rather forlorn Peter, the acne on his face more pronounced and clearly visible on his shoulders. At age sixteen he is no longer among the tallest. And he no longer stands tall. What happened between these two photographs helps to explain the change.

On Thursday, August 24, 1950, after a two-week hospitalization, Margaret Brown died. Peter claimed that no one had told him of her illness. The news came as a shock. Margaret was only forty. In announcing her death, Galt’s Evening Reporter of August 25 listed her relatives as Reg Brown, Peter, the late McGregor Young, Margaret’s mother, her sister, Jean Rowe and her brother, Brigadier Gregor Young, all of Toronto. Harold Gzowski received no mention.

Her funeral was held on Sunday, August 27, at Little’s Funeral Home in Galt. The next day the Reporter noted that Harold had helped to carry his ex-wife to her grave at Galt’s Mount View Cemetery. The papers, of course, didn’t report the cause of her death, but the town was already speculating. In small towns, neighbours not only know of excessive drinking but exactly where in the house the drinker hides half-empty bottles. In hushed tones, the townsfolk talked of cirrhosis of the liver. At the funeral and afterward at the tea, Norma Brown, sister-in-law of Reg, noticed the abandoned sixteen-year-old, silent and slouching in a corner. Peter seemed a pleasant young man, she thought, but perhaps because he was shy, and no doubt overwhelmed by grief, he kept to himself. His mother’s death, “and the years of loneliness and unfulfilment that led up to it,” he wrote in his memoirs almost four decades later, “scarred my soul more than the acne marked my skin. I miss her still.”7 The memory of her brought tears to his eyes on CBC’s Life & Times.

Ridley College basketball team, March 1950 — Peter in back row, second player from left.

(Courtesy Paul Lewis and Ridley College Archives)

When he returned to Ridley in September 1950, Peter didn’t grieve. At least outwardly. In fact, some of his mates there can’t recall that he even mentioned his mother’s death. It wasn’t the manly thing to do. After all, Ridley, like all private schools, taught Peter muscular Christianity. A man wasn’t expected to show his emotions, and young men and boys were governed by expressions such as “take it like a man.”

However, Peter remembered his Ridley years as “three of the best years” of his life. No doubt student shenanigans helped take his mind off his grief. He reported in a Maclean’s article of 1961 that one day, or more likely one night, a group of boys carried the history master’s tiny English car up to the second floor of the building where they took their classes.

College sports were also a welcome diversion. In the autumn of 1950, he was an alternative for the Ridley football team, and in one photograph he stands with other alternative players in Varsity Stadium in Toronto. Behind them is a view of Bloor Street. He was determined to make it to the first team. During the summer of 1951, he practised throwing footballs. When he returned to Ridley in September, he so impressed the coach that he was asked to play quarterback on the first football team. In the team photograph, Peter is standing in the back row on a chilly November day in 1951. He sports a broad grin. John Girvin is in the photograph, and so, too, are Jim Conklin and Jack Barton. Headmaster Hamilton sits in the centre. The quarterback holds a football marked 1951. Around his neck Peter is wearing a sling that holds up his right arm. In the Globe and Mail of December 22, 2001, he offered an explanation. During tackling practice, he had crashed into John Girvin, a collision that resulted in a broken bone in Peter’s right hand. Years later, in a column for the Toronto Star, he upped the ante by claiming he had broken two bones in his hand. In an article in Saturday Night in January 1965, he claimed that, while playing football, he had broken a bone in his foot. Soccer was less strenuous, and Acta Ridleiana, the Easter 1951 issue, shows Peter and ten other members of Dean’s House Soccer Team.

Ridley was, however, more than just pigskin, broken bones, and books. The Midsummer 1951 issue of Acta depicts a group of partying boys, all smiling and laughing, especially Peter, who throws back his head, closes his eyes, and laughs harder than anyone else. Acta published a few of Peter’s short articles. In the Easter 1951 issue, he argued in favour of Sunday sports. “Self-righteous dowagers and demagogues have slandered the very name of Sunday sport, crying piteously that it is heresy and sacrilege,” he wrote in a self-confident style with an overlay of pretense. He believed that “Sunday afternoons should become a Canadian institution, something to be proud of like maple trees,” adding that since gas stations and drugstores were allowed to remain open on Sundays, why not sports stadiums? He quickly put paid to the argument that Sunday sports would lead to Sunday movies, grocery stores, pool halls, and beer parlours. He was a bit ahead of his time — Premier Leslie Frost, municipal politicians, and indeed a majority of Ontarians weren’t ready to follow Peter’s advice.

Autumn 1950 alternatives for the Ridley College football team at Varsity Stadium on Bloor Street in Toronto, Peter in the middle.

(Courtesy Paul Lewis and Ridley College Archives)

On May 4, 1951, the Ridley Sixth Form (grade twelve) held a debate: “Resolved — that a camel makes a better house pet than an elephant.” Master Pringle was the “speaker” or moderator. Peter, who debated under the title “an Honourable Member from the Orient,” argued for the negative. He informed the audience that “the elephant was a great animal,” and threw in “numerous quotations” to prove his point. He had prepared carefully and possibly had consulted an encyclopedia and some of the other books in the school library.8 When the debate began, the audience was evenly divided, but Peter’s argument persuaded them to vote in favour of the elephant.9

In the Christmas 1951 issue of Acta, P.J. Gzowski’s “Term Diary” for the previous autumn term appeared: “September 12, Here we go again.” The next day, he reported, the football squads started to work out. The day following, his comment was “Oh my aching joints.” On October 5, “Peter Sutton’s hula girls amuse us greatly — very educating.” On October 19, when a rival football team defeated Ridley 33–12, he wrote “Pardon the tear-smeared page,” adding that a “very interesting liquid air lecture consoles us somewhat.” He was pleased to report on October 29 that a jukebox had been installed at Gene’s confectionary store near the campus.10

One of Peter’s last articles at Ridley was entitled “Some Hints on Memory,” an amusing, self-deprecating short essay that provided tips on how to remember things. Licence numbers were memorable if broken into meaningful pairs of numbers, giving an age, a year, and so on. To remember laundry day, Peter tied a handkerchief around his wrist on Sunday evening. The following Thursday, when it began to smell, it was laundry time. “I have noticed,” he wrote, “that some boys around the School have tried to accomplish the same thing with a shirt or a pair of socks but I find the handkerchief less offensive.” His final tip was to set important dates and events to rhyming couplets. His first verse was about the upcoming Mother’s Day: “Though she may be far away / Please remember Mother’s Day,” lines both poignant and cheeky. The second verse was advice on how to avoid getting caught smoking: “Prefects check at half past ten / Then they go to sleep again. / Remember they are in a rut: / Eleven o’clock’s the time to butt.” And his third verse was how to get back into one’s room after curfew. He bragged that even his roommate, whose name he couldn’t recall, complimented him on his memory. He was so proud of this article that, more than thirty-five years later, he included it in A Sense of Tradition.

That he had become more self-confident and slightly cocky during his last year at Ridley shows in his writing style and ironic attitude. The March 1952 photograph of the first basketball team reveals a young man who is no longer the confused boy who cowered at Dean’s House two years earlier. At seventeen he seems more relaxed, the scars of acne no longer an overwhelming problem. His upper body muscles are developing, and he is becoming quite the handsome, self-aware lad.

Peter’s accounts of a trip to a bar on the American side of Niagara Falls also revealed a cocksure nature. In Ontario the legal drinking age was twenty-one; however, it was eighteen on the American side of the border. One version of the story appeared in an article written by Peter in 1970 for Saturday Night. After chartering a bus to Niagara Falls, Ontario, several of the boys from Ridley walked over the international bridge, spent time in a bar, and got drunk. Others only pretended to be drunk, for they didn’t want to be teased for not drinking. Two or three honest, sober boys were ostracized. In retrospect Peter admired their honesty but carefully avoided explaining his own role in the incident. The reader might be tempted to guess that he was one of the young men who merely faked inebriation. There are, naturally, many variations of the drinking story.11

There was one episode, however, for which there is only one version, because Peter never wrote about it. One dark evening, probably in his last year at Ridley, Peter was returning to the college. He was desperate for another smoke. He had a cigarette but no match. In the dim light of a street lamp, he came upon another solitary walker. “Gotta light?” he asked the man. The man reached into his pocket, pulled out a penny match packet, and proceeded to light a match. Mere inches apart, their faces glowed in the amber light of the match. As Peter sucked at the end of the cigarette, the man quietly asked “Wanna fuck?” Peter dropped the cigarette and ran. He reached the college dorm, tore up to his room, and was so agitated that he couldn’t speak. “What’s the matter, Peter?” asked John Girvin. It took Peter several minutes to calm down enough to recount the episode. Girvin never forgot that night. Peter, apparently, did, for in Canadian Living in March 1998, he wrote a loving article about Girvin called “Chums by Chance,” in which there is no mention of the proposition on the bridge. Instead, Peter recalled only that each night he and Girvin “would lie awake in our room and talk of girls, dreams and home.”

Strangely enough, in the first Morningside Papers, published in 1985, Peter and his editors decided to include a short chapter called “The Closet,” which consists of two letters, both of them on the subject of gay men. Coincidentally, St. Catharines and a boarding school play roles in each letter, which were sent to Peter after two people, strangers to each other, had heard a Morningside interview with novelist Howard Engel, on the subject of a gay man in St. Catharines who had committed suicide when he discovered his name on a police list of men who had enjoyed sex in a public toilet. Of course, it is improbable, after more than thirty years, that the man in St. Catharines who committed suicide was the same man Peter had met on the bridge about 1952. The first letter in “The Closet” was from a married man, the father of two children. To all appearances, he told Peter, he was happy. He did have, however, a dark side. “I want anonymous sexual encounters,” the man confessed. “They must be anonymous because I just cannot afford them being anything else.” From Duncan, British Columbia, came a second letter that told of a gay teacher in an unnamed boarding school who was forced to resign. Peter made no comment.

Peter graduated from Ridley in June 1952 with honours. He was awarded the Kelly Matthews Memorial Prize for mathematics, physics, and chemistry; received the Julian Street12 Prize for prose; and cadet platoon number four, of which he was the sergeant,13 won second prize. Peter also won the William H. Merritt Prize for public speaking, a prize that caused a bit of controversy. Each year the winner repeated the speech to the Rotary Club of St. Catharines. His topic was a comparison of American culture to human waste. American culture, he contended, developed at the same time as outdoor facilities moved inside and as toilet paper replaced stiff, glossy pages from shopping catalogues.14 As human waste grew more sanitized, American popular culture grew more insipid, proof being the movies of Shirley Temple and the Andy Hardy films of Judy Garland and Mickey Rooney.

In the end, Ridley authorities did allow their best public speaker to address the Rotarians, whose reaction went unrecorded. Peter was also awarded two university scholarships. In a photograph of Upper School prize winners, Peter looks proud as he poses in shirt, jacket, and tie, in the back row, with other prize winners, including John Girvin, on Peter’s left, as well as Jim Chaplin, R.K. “Shiggy” Banks, Andre Dorfman, and other bright young adults ready to face the world and to make their contributions to it.

Peter remembered his years at Ridley with great affection. “I belonged. I was a part of something in a way I have seldom been since,” he wrote in the Toronto Star on November 28, 1978. Even though he claimed that his year as editor of The Varsity, 1956–57, and his months as city editor of Moose Jaw’s Times-Herald, were also his happiest, there is no doubt that the high standards and strict discipline of the private school left a lasting impression, as well as many topics for books and articles. To be at his creative best, Peter always required imposed discipline.

A teenage Peter with sign this structure in disrepair. persons using it do so entirely at their own risk, perhaps on a construction site?

(Trent University Archives, Gzowski fonds 92-015/1/34/Photographer: Michael Gillan)

In September 1952, Peter entered the University of Toronto. By that time, the young adult, less self-conscious, was beginning to cope with the scars of acne. What he couldn’t handle was the lack of Ridley discipline. Years later he told a reporter that he wasted time playing crap games with taxi drivers. He drank at the King Cole Room in the Park Plaza Hotel and attended parties at his frat house, Zeta Psi, at 118 St. George Street, just north of Harbord Street on land now occupied by the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library and the university’s archives. One autumn weekend the University of Western Ontario football team was playing at Varsity Stadium in Toronto. John Girvin, a member of the Western team, visited Peter, who took him over to his frat house and showed him his initiation scar. Zeta Psi had welcomed Peter in typical fashion by imprinting its insignia into his arm with a branding iron.15 Since he was under oath to keep the practice a secret, his fellow frat members, including Scott Symons, weren’t pleased. According to Symons, Peter was “a real asshole.”16 It might have been at this time that Peter bragged to Girvin that he wasn’t going to read any assigned texts until just a few weeks before final examinations. Already, it seems, he had developed an ability to assimilate books by skimming them. He managed to scrape through his first year with a C-minus. Ironically, as editor of The Varsity four years later, one of Peter’s first pieces of advice to new students was to avoid cramming just before exams.

According to the university directory of staff and students for 1952– 53, during his first year, Peter lived at 73 St. George Street in a house once inhabited by Sir Daniel Wilson (1816–1892), who was associated with the University of Toronto from 1853 to 1892 and was president of the institution from 1889 to 1892. During most of his four decades in Toronto, Wilson had been a friend and colleague of Sir Casimir Gzowski.17

The Toronto City Directory gives a second address for Peter in 1952 at 32 Tranby Avenue, a street running west off Avenue Road between Bloor Street and Davenport Road in the district known as the Annex. In the 1950s, its attractive brick Victorian homes were being broken up into apartments and rooms. On the upper two floors of a handsome semi-detached, three-storey red-brick house18 lived Peter’s father. It was to this house that Peter escorted Girvin to meet his father during that football weekend. Peter may, in fact, have stayed there on weekends while visiting Toronto from Galt during the late 1940s and on weekends away from Ridley College in the early 1950s. He admitted that possibility when interviewed by Marco Adria in May 1992, though he probably didn’t want to be too precise, for he always liked to claim estrangement from his father.

By 1952, Brenda (Raikes) Gzowski had obtained a divorce and had returned to England. Girvin remembered meeting a woman whom Peter called his “stepmother.”19 In 1952, “Mrs. Camilla Gzowski” was the co-owner of 32 Tranby. Camilla ran Harold’s office, probably from a room in the house on Tranby. Harold sold awnings. In the 1950s, aluminum awnings were all the rage with suburbanites in North York, Scarborough, and all those other post-war residential developments. Camilla may have brought money to the marriage and invested it in the house and business. The co-owner of the house was James B. Drope. Peter claimed that Jimmy was a bootlegger. In the city directories, he is listed as a “manufacturer’s agent,” who may have bought home-distilled liquor from “manufacturers” and resold it tax free. The strict liquor control laws of Ontario during the days of Premier Frost encouraged bootleggers, who had no difficulty finding customers. According to Peter, Drope had once spent time in the Guelph Reformatory. While Jimmy stayed at the house for several more years, Harold and Camilla, according to city directories, seem to have moved on by 1953.

In order to earn tuition money, during the summer of 1953, Peter worked in northern British Columbia on the construction of a power line to link Kitimat’s aluminum refinery with Kemano, a hydro-electric station forty-five miles inland.20 Some forty years later, in an introductory billboard or essay on Morningside, Peter talked about his work at Kitimat. His fellow workers, he told listeners, came from across Canada and around the world, from Newfoundland, the Prairies, Quebec, Portugal, Finland, and Saudi Arabia. “I was eighteen,” he went on. “After writing my first-year exams, I had taken a bus to Vancouver and signed on for the float-plane north.” He lived in a tent with a wooden floor, he fed cookies and sweetcakes to black bears, and once, by using an orange as bait, Peter’s tent mate coaxed a bear into the tent. The food was good but the work was tough, the hours long, and the weather wet. While wearing his “blue university windbreaker, class of 5T6,” he operated a shovel with a nine-foot handle that mulched out the footings of the power line. In a big recreation hall, if the men didn’t like a particular clip during one of the free movies, they stomped so loudly that the projectionist was forced to put on the next reel.21 Behind the hall was a gambling tent. Years later a Morningside listener reminded Peter that Bertrand Bélanger from Arvida, Quebec, had taught workers French three days a week, and that each Friday fresh meat, milk, and vegetables arrived by boat at the Hudson’s Bay Company store. Another Morningside listener, who had been in Kitimat in 1953, remembered “a young clean-cut and friendly feller with the same name as yours … always very friendly and polite with us emigrants.”22

After the residence at 73 St. George Street was razed in 1953 to make way for a new men’s residence, the occupants were relocated temporarily on Grenville Street near the corner of Bay and College Streets, and that was where Peter lived during his second year at the University of Toronto.23 Apparently, he did little academic work. During the summer of 1954, he worked as a surveyor on railway construction in Labrador. It was perhaps his father who got him the job, or who inspired him to go to Labrador. Harold had also worked on railway construction from Sept-Îles north into Labrador, and that may be where he met his third partner, Édith.

Nine years later in Maclean’s, Peter wrote two articles (November 2 and 16, 1963) about working on the Quebec, North Shore & Labrador Railway, built to carry iron ore from Knob Lake, Labrador, 300 miles south to Sept-Îsles. Like all the workers, he was treated, he claimed, like a serf by the construction company. He slept in filth and ate dismal food. By far the biggest problem were the blackflies, which feasted on the construction crews and the surveyors, even though the construction company sprayed the work areas from an airplane and doled out gelled repellents, which, Peter speculated, may have contained DDT. Even on the hottest days, Peter and the other workers kept their shirt sleeves rolled down and their pant legs tucked into their socks. “Everyone I saw,” Peter wrote in Maclean’s (November 16, 1963), “was bitten behind the ears, down the neck, in the belly.” A bulldozer operator, who had to keep both hands on his machine, suffered a nervous breakdown because of the flies.

There was one great pleasure, Peter recalled, and that was fishing in the Moisie River. Since it was so easy to catch the plentiful salmon, as well as trout and pickerel, Peter grew bored with fishing and turned to magazines such as True, Ace Detective, and whatever else he found in the camps. He also played poker.

What he failed to mention in Maclean’s was his experience in a gay bar in Montreal while he waited for his train to Sept-Îles. In his papers at Trent University Archives, he left a document, perhaps a rough draft of an unpublished article, which describes the incident. Because he wanted a taste of the wicked side of Montreal, he didn’t tell his Gzowski relatives that he was in the city. At Central Station, while picking up his train ticket, he met “a short man not much older than I,” who was going to Labrador as a cook. The two men adjourned to the beer parlour in the Mount Royal Hotel near Peel and St. Catherine Streets, and ordered a quart or two of beer. It took Peter a while to recognize that they had entered a bar frequented by gays. To use Peter’s term and the one employed in the 1950s, it was a “queer” bar. At almost twenty he was tall and broad-shouldered with slim hips. He would have been noticed the moment he entered the bar. The young cook introduced Peter to some of the other customers. Two men joined Peter and the cook at the table and carried on a dialogue in French. Occasionally, they looked at Peter and smiled. He grew uncomfortable. When he announced that he had to go, the cook told him that one of the men, Gilles, wanted to take him out for dinner. Peter responded by throwing a couple of dollars onto the table and walking out. He ate by himself in a steak house and wandered the streets until the train left at midnight.24 Inevitably, he ran into the cook at the construction site, but in the unpublished article he doesn’t say whether he ever again communicated with him.

Surely, however, Peter couldn’t have been as naive as he depicts himself in the unpublished document. In fact, Harold Gzowski once introduced his son to “a certain wicked adult institution” of Montreal, so Peter recounted one morning when Morningside was broadcast from that city in 1984. Peter didn’t give the year, but the visit was perhaps soon after the death of his mother. Did Harold take him to see Lili St. Cyr, the famous stripper, at the Gayety Theatre on St. Catherine Street near St. Laurent Boulevard? Or did his father introduce Peter to a brothel? Peter concluded his Morningside account by telling his listeners: “This city excites me, and marks moments in my life.” In the early autumn of 1954, Peter was back in Toronto. He probably didn’t even bother to register at the University of Toronto.25 For a short time, he worked for the Hydro-Electric Power Commission of Ontario, probably on St. Lawrence Seaway construction. In October he spent a few days at his paternal grandparents’ apartment at 39 Rosehill Avenue near Yonge Street and St. Clair Avenue, where they had lived in a small third-floor flat since the late 1930s. Once the devastating floods caused by Hurricane Hazel had receded, Peter boarded a train for Timmins to work at the Daily Press. The job was the result of knowing Ed Mannion, who had once played badminton in Galt with Margaret Brown. Mannion was at the Toronto headquarters of the Thomson chain located on the top floor of the Bank of Nova Scotia skyscraper at King and Bay Streets. A friend of Margaret’s in Galt had telephoned Mannion to ask him if he could find a job for Peter. Mannion discovered that the Timmins paper needed an advertising salesman. Although Peter had little interest in selling ads, the job allowed him the vicarious pleasures of deadlines and printers’ ink.

Over beer at the Lady Laurier Hotel, he pestered reporters and editors to let him become a reporter. Robert Reguly obliged. Peter’s first published piece was a five-paragraph report on a speech delivered at the Beaver Club of Timmins. The only problem, Peter admitted in his memoirs, was that he hadn’t written it. Yes, he had typed it, but it had been dictated by Reguly.26 Why? For the simple reason that, when Peter arrived in Timmins, he couldn’t write in a good journalist’s style.27 In Timmins he memorized the Canadian Press Style Book, which taught him that accommodate has two c’s and two m’s; that infer means something different from imply; and that unique is absolute.28

Peter and Reguly rented suites in the Sky Block, a small apartment house featuring shared toilets, one for every four suites, and hot plates in each tiny suite. Once a week, Peter, Reguly, Chris Salzen, and one or two other reporters adjourned to the Finn Boarding House, where for eighty cents they could eat all they wanted. The only problem was that if they didn’t arrive early the meat was gone and they had to dine on potatoes. Occasionally, reporters adjourned to the Riverside Pavilion across the river in Mount Joy Township. “The Pav” was an illegal booze joint and dance hall. Customers brought their own liquor, and the club provided the mix. It was frequented by, among others, the mayor of Timmins and a local priest known as the Black-Robed Bandit, who, according to rumour, was a part owner of The Pav, whose chief purpose was to act as a pickup joint. Most of the men left with a woman, but never Peter, who was overly shy.29 His story, recounted in a radio essay on This Country in the Morning, about “trying to get a goodnight kiss when it was fifty below and walking home across a northern Ontario town because the buses had all stopped running,”30 should be taken with a grain of salt.

Soon Peter was in charge of the cultural beat of the Daily Press, with help one evening from a “pretty piano teacher.” Over drinks at the Empire Hotel, she helped him write a music review, with near disastrous results when they reviewed a performance by Jeunesses Musicales du Canada without having heard the concert. The youth orchestra hadn’t been able to make it to Timmins through a snowstorm. Peter caught the review just before it went to press.31 This story has variations. In an article in Saturday Night in 1968, Peter claimed that he had taken the “pretty young piano teacher” with him to a recital in South Porcupine “to make sure that I didn’t deliver an incisive analysis for the next day’s paper on a piece the visiting artist neglected to perform.”32

Peter always loved acting, onstage or off. He was active in the Porcupine Little Theatre in Timmins, and in his memoirs, he claims that he reviewed a play — perhaps Springtime for Henry — in which he had a part. In The Man Who Came to Dinner, produced in the spring of 1955, Peter had the starring role of Sheridan Whiteside, the outlandish and witty radio broadcaster from New York City. Whiteside is invited to dine with industrialist Ernest W. Stanley, a role played by Chris Salzen. Denise Ferguson, whose acting career later flourished, also had a role. Just before Christmas, Whiteside slips and injures his hip in front of the Stanley house. He makes two things clear: that he intends to remain in the house until his hip is healed, and that he is going to sue Stanley. From his wheelchair, he insults everyone, including the local doctor.33

Are actors drawn to roles that suit their personality? Did Peter even then long to become not only a good journalist but also a witty, famous, and curmudgeonly broadcaster? Is it possible to imagine oneself into reality?

April 1955, Chris Salzen standing, and Peter as Sheridan Whiteside, the crusty journalist in the Timmins Little Theatre production of The Man Who Came to Dinner.

(Courtesy Chris Salzen)

Peter also enjoyed performing solo. One day he did a skit for the local Rotary Club. The script had been sent to the club from headquarters. Most of the script had been recorded earlier on a big tape recorder, and Peter acted as the live narrator who happily bridged the gaps between the various recorded scenes. The play was really meant for radio, but the narrator, much to the amusement of the Rotarians in Timmins, brought it to life on the stage.34

Inspired perhaps by his acting career, by the Canadian Players’ touring version of George Bernard Shaw’s Saint Joan, and by CBC Radio drama, broadcast from Toronto and picked up by CKGB, a CBC affiliate one floor above the Daily Press office in Roy Thomson’s attractive art deco headquarters,35 Peter co-wrote a radio play called Christmas Incorporated. Its characters include Paul, an unhappy businessman; Chris, a stranger; Paul’s wife, Kay; and Paul’s young daughter, Jill. On Christmas Eve, Paul meets Chris at the Empire Hotel and invites him home for dinner. At midnight Chris leaves. A few minutes later Kay’s brother, George, arrives, inebriated as usual. He surprises his sister and brother-in-law by announcing that he is going to quit drinking. On his way to their house, George tells them, he passed a sleigh and eight tiny reindeer hovering in the air. He saw a man climbing a rope ladder into the sleigh. The identity of their departed visitor slowly dawns on Paul and Kay. Chris is a combination of Santa Claus and Christ. A children’s choir sings “O Come All Ye Faithful.” Paul and Kay go upstairs to get Jill so that she, too, can listen to the singing. Before they turn on the tree lights, they wish one another a merry Christmas.

Peter was no doubt influenced by movies such as It’s a Wonderful Life (1946), Miracle on 34th Street (1947), A Christmas Carol (1951), and other cinematic morality tales that portrayed the triumph of generosity and love over greed and materialism. The play, which bears the marks of two young and earnest playwrights, incorporates themes that later grew in importance: Peter’s indifference to materialism and personal appearance; his battles with alcohol and depression; and his strained family relations. Peter must have been thrilled when the play was broadcast on CKCL, a bilingual radio station a couple of blocks from the Thomson building.36

In his memoirs, he confessed (or bragged) that he had faked a photograph. In the spring of 1955, he was sent out to a raging fire near Timmins. On the edge of the fire was a spruce tree with a sign that warned about the dangers of forest fires. Nearby was another sign about the dangers of smoking. He moved the second sign to the lone spruce tree, just under the first sign. The only problem was that his tree “stood in unspoiled symmetry, a cool green sentinel amid the onrushing inferno,” so the young reporter plunged a pine branch into the nearby fire and ran back to his tree with the burning torch. The tree caught fire, and he got his picture. He rushed back to develop the photo. It appeared in the Timmins paper under the headline “Do Not Set Out Fire Without Permit,” but with “Daily Press Photo” not “Pete Gzowski” as the photographer. On May 24, 1955, when the photo appeared on the front page of Toronto’s Telegram, it was attributed to Don Delaplante. Might one assume that not only did Peter fake the photograph but that he concocted the whole story about the authorship of the article? As he noted in his memoirs, he never let reality “stand in the way of a good story.”37

Nevertheless, Peter claimed that the photograph, which won an award, was his ticket to success. In announcing his promotion, the Timmins paper claimed that “Pete” had been at the University of Toronto for two years and that he had studied philosophy and English. No doubt Peter had fed the paper that rather optimistic account of his studious university career. When he was promoted to the position of reporter at the paper’s Kapuskasing bureau, his articles began to appear in both the Kapuskasing Weekly and the Daily Press. On Wednesday, August 3, 1955, under “Pete Gzowski, Staff Writer,” he wrote about yet another raging forest fire, but this time from a point high above in a Lands and Forests Otter aircraft. He also wrote about teenage figure skaters at practice in Porcupine during the hot summer of 1955, about water fluoridation in the township of Tisdale, and on the possibility of the National Ballet of Canada performing in Porcupine. Peter visited an art exhibition in Porcupine, and one week he produced a humorous issue under the headline “Too Much Bad News Printed? Here’s Something Cheerful,” in which the unnamed staff writer of the Kapuskasing Weekly, no doubt Pete Gzowski, printed only good news. He reported, for instance, that Bruce MacDonald had just celebrated his birthday.

Peter was always full of mischief. One snowy day, while out for a walk with Chris Salzen, he passed a public school during recess. He started shouting, “Monsters, beasts,” and threw snowballs at the children. Delighted, they returned fire. One day, just before Christmas 1954, Reguly, Salzen, and Gzowski were quaffing beer at the Lady Laurier when Peter came up with a brilliant idea. Why not adjourn to the Metropolitan Stores outlet, one of a chain of discount department stores, where they would sing Christmas carols? That way, Peter explained, they could brag that they had sung at the Met. They did, and they bragged for weeks afterward. Never once, apparently, did he allow his fellows to see inside his bright mind. Years later, when Chris Salzen first heard Peter on CBC Radio, he was surprised at just how bright his former colleague could be.

In September 1955, probably somewhat reluctantly, Peter returned to the University of Toronto. The university directory notes that he stayed at 12 Walmsley Avenue in the Yonge and St. Clair area — in other words with his grandmother Young. The directory also notes that he was in his second year, which means that he actually failed his first attempt at a second year in 1953–54. To help pay for his tuition, he worked as a part-time reporter for the Telegram, which hired him to write about crime and punishment on the police beat. From 1:00 a.m. to 9:00 a.m., he sat at a desk at police headquarters at 149 College Street, just west of Bay Street, where he monitored police radio reports and checked precincts, fire halls, and emergency wards. At the end of the shift he sent stories by taxi to the Telegram, with a duplicate to the Toronto Star. Each morning at 9:00 a.m., as he shuffled along College Street to the nearby campus, he imagined himself as the actor Leslie Howard, “wan and dreamy,” a volume of Dylan Thomas under his arm. His salary of $55 per week also paid for beer at the King Cole Room and for any entertainment in his “dingy basement” apartment on Tranby Avenue. He may have made arrangements with Jimmy Drope to sublet the basement flat for occasional use when Grandmother Young’s rules might have been too restrictive.

As a general reporter for the Globe and Mail, Robert Fulford was sometimes assigned the police beat from early Saturday morning to Sunday afternoon. In his memoir Best Seat in the House, Fulford recalled that Peter once arrived at police headquarters with a book of poetry by John Milton. When Fulford asked him if he enjoyed Milton, Peter replied, “‘Hell, no. It’s on the course.’” Fulford concluded quite rightly that Peter was camouflaging his intelligence in order to be considered one of the boys.38

That year Peter was also the managing editor of Gargoyle, the monthly magazine published by students of University College, the non-denominational college of the university. On February 8, 1956, Gargoyle published an article by “Pete Gzowski.” Leon Major was directing rehearsals for the musical Kiss Me Kate, starring Donald Sutherland, the twenty-year-old native of New Brunswick.39 Interviewing Major, noted Pete Gzowski, in one of his more contrived similes, was “like trying to play gin rummy with a tongue-tied auctioneer.”

During the summer of 1956, Peter joined Clyde Batten in publishing a weekly called The South Shore Holiday, which reported on the cottage areas and towns along the east side of Lake Simcoe from Beaverton to Keswick. The publication was based in Jackson’s Point, probably at Betlyn, the Colonel’s summer home. In the first issue of May 18, Batten and “Peter J. Gzowski” introduced themselves in an article entitled “This Paper’s Editors Young but Very Eager.” Journalism was Peter’s “one true love.” If all went well, he would graduate from the University of Toronto the next year. The issue also included an article called “Shooting the Wedding,” an amusing look at nuptial photography by Alf Brodie, who called himself “the voice of the Beaverton Bandwagon.”

The South Shore Holiday was printed each Thursday at the offices of the North Toronto Herald on Yonge Street, following which Gzowski and Batten drove it up to numerous general stores along the lake. The weekly published Peter’s reviews of plays produced at the nearby Red Barn Theatre, and the pair “borrowed” articles from the Toronto papers. By altering the byline and the opening lines, they managed to get away with plagiarism. When it became obvious that The South Shore Holiday wasn’t going to pay the cost of university tuition, it folded. Batten and Gzowski forgot to tell Alf Brodie, who, according to his daughter, Judy, was left “high and dry.”40 Brodie’s diary talks only about Batten, as if he were the real star of the weekly.41 Peter finished the summer working on the St. Lawrence Seaway construction.

By the mid-1950s, the inkwell and the fountain pen had almost vanished from everyday use, replaced by the more convenient ballpoint pen. For the rest of Peter’s life, ink was his mainstay, whether the pen or the ink-imbued ribbon of a typewriter, the printer’s ink of newspapers and books, or the ink cartridge of a computer printer. Beginning with those rather earnest, sometimes witty short pieces in Acta Ridleiana in the early 1950s and ending with Peter’s final article in the Globe and Mail in January 2002, he expressed his opinions and developed his imagination with the help of that bluish-black liquid that was sprayed and pumped so dramatically at Ridley one raucous evening in 1950, the night when he finally felt that he belonged. If the pen is indeed mightier than the sword, it is the ink in the pen that deserves the credit. Even more important is the intelligence and wit of the person holding that pen or pecking at a keyboard.