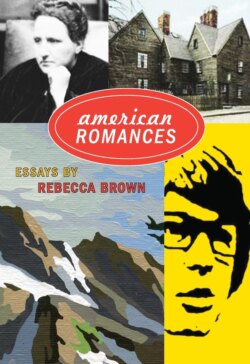

Читать книгу American Romances - Rebecca Brown - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Hawthorne

Оглавлениеa) Nathaniel, American author (1804-1864).

b) California suburb where Brian Wilson, American composer and Beach Boy (1942- ), was raised.

Oh, the sins of the fathers! Oh, the visitations upon the sons! The dream of America! The nightmare, the horror, the hope.

The Puritans dreamt of the City on the Hill and came to the New World to build it.1 Then when it went to hell their sons and sons of sons went west, and daughters, too. Go West, Young Man! Get away if you can! Get out before the city you built upon the hill implodes and takes you with it! Go West, Young Boy! The future’s there! And beaches, too! Your Destiny and ours, both Manifest and otherwise, are way out west, far out, in the place the sun goes down each day and dies.

And so, to California they went, eventually to Hawthorne, suburb of the City of Angels. It was as far as they could go because then the land runs out, the only thing beyond is water, which no one can, unless they’re Jesus, walk on, but they tried (on surfboards) and to some degree they could, but then they couldn’t.

Because as much as anyone tries to ride a wave, a wave can’t last forever. No surf stays up for good. It crashes or it comes ashore. It’s soaked up by the sand, sucked down to earth, then further down, as they both say and sing, to hell and back again.

They set out with their modest, pure, angelic wives and found on the other coast the tanned and leggy, long-haired girls, perditious daughters of their bedeviled dreams. The Goodwives of Plymouth, Massachusetts, who covered the vanity of hair and clothed themselves in abstentious garb had mostly been obedient, Anne Hutchinson not-withstanding.2 Though she was a deviant, wasn’t she? Iniquitous. But way out west their malefactress daughters uncovered, grew, then cut their hair (Where did their long hair go?), the sons grew theirs, and everyone removed their sober clothes. Their children and their children’s kids who’d been spared not the rod, were scruffy, unwashed, drugged and had an awful lot of sex. (See Manson, Charles, friend of brother Dennis, drummer, the cute one.) The daughters who’d been silent, pure (of, like, or as a Puritan) reported they’d had concourse with the Evil One who’d come to them in bodily form, sent by those they accused. They called these others witches (hippies, commies, terrorists) and they were stoned. They threw them in the water and they drowned. Like surfers who aren’t strong enough, or are, except when some great, unexpected wave, a giant maw as big as the whale that got Gepetto although without a wooden puppet come to rescue, swallows them.

How deep is the ocean?

Enough to drown us all.

Some things, no matter how far apart, occur again the same. They happen the same again and over again. The same except for different, and forever.

The witches were condemned to drown.

Like Dennis Wilson drowned. When he was stoned.

Whose story is this anyway? Are fathers always sons? Does history ever only happen once? Is there a lesson here?

The hardness of the hardened heart? The willful weakening of flesh? (It rots when unattended to; it putrefies.) The silence of the damning stare? (The Puritans didn’t dance.) A boy’s belief in angels’ song? Or Goodman Brown, my father’s name, no longer Young, delighting in the dark unrighteous night?

A hero turns into a villain

once and then he turns again.

And I can’t tell a lesson from a blame.

Our Puritan forebears—and some were mine, my mother’s mother Doty having traced us back to an indentured servant on the Mayflower—landed on Plymouth Rock, having come west to start over in the New World; then, having completely fucked over this paradise, moved west again, across the continent, to attempt again what they failed at before and ended in up California, dreaming.

Hawthorne, writer from the east, and Hawthorne, suburb in the west, are twisted in a Mobius strip: the child and its evil twin, the maker and its son.

The City on the Hill became the suburb in the sand.

Nathaniel Hawthorne’s great-however-many-grandfather, William Hathorne (note no “w” in the old man’s name; we’ll get to that later), was among the first Puritans to emigrate to New England in 1630.3 His westward move was made in a ship, and it wasn’t easy. There was all of that sickness and puking and death. That leaving behind and forgetting and not forgetting. All of that forever goodbye and never return and always wonder. William Hathorne first settled in Dorchester (Why did they name new places after old places they had left? Because no matter how much you want to, you never unbecome the place you came from), Massachusetts. He only stayed a while and then he moved to Salem where he thrived. Nathaniel Hawthorne, in “The Custom House,” the introductory chapter to The Scarlet Letter, describes “[t]he figure of that first ancestor” as “grave, bearded, sable-cloaked, [a] steeple-crowned progenitor … with his Bible and his sword … soldier, legislator, judge; he was a ruler in the Church, he had all the Puritanical traits, both good and evil. He was likewise a bitter persecutor.”4 This William became deputy to the General Court of Massachusetts, speaker of the house, commissioner to the board of the United Colonies of New England and a renowned Indian Fighter (read: Genocider. For “Thou shalt not kill” did not apply to subhumans, which, though they were the ones who welcomed them and fed them, helped them stay alive, was how our forebears regarded the people who were already living on this continent). William Hathorne also was a judge and, in keeping with the Puritan justice his people had suffered in England but then brought with them because no matter how much you want to you can never unbecome the thing you are, meted out harsh punishments against evildoers such as: cutting off ears; boring holes in women’s tongues with red-hot irons; starvation; dragging naked women through the streets while having them flailed by a constable with a cord-knotted whip, thus drawing blood, the desired result known as “stripes” (as in Isaiah, which the Bible-quoting Puritans would know, though we, godless and godforsaken souls, if we know it at all, probably picked it up from Handel’s Messiah: “and with his stripes we are he-e-e-e-e-e-e-e-e-e-e-e-e-e-e-e-a-led”). The gallows. Putting into stocks. The pillory. Thumbscrews. Shackles (metal fastenings, usually a linked pair for the wrists, ankles, or both. See also: fetter, manacle. Also, any thing that keeps one from acting, thinking or developing as one desires. Remember them). Public humiliation such as having to walk around with the name of your crime written on a board hanging from your neck, and the board, being also very heavy, leaving marks on your neck and shoulders when—that is, if—you get to take it off. Drowning. (If she floats she’s a witch, if she’s innocent she drowns. There’s water enough for all of us.) Stoning. Stretching on a rack, ripping off toe- and/or fingernails, ridicule, scorn, water boarding, throwing feces on, threatening with dogs, blinding with black hoods, prodding with electric prods, pissing on their holy books, making them do humiliating sexual things with themselves and with each other while photographing them and photographing ourselves making them do these things, thumbs up, hamming it up, grinning for the camera—

Wait a second. They didn’t do all of those things back then, did they? Electricity hadn’t been invented yet, nor photography. They only did some of those things. The other things had to wait until, through rational inquiry and scientific progress, we invented them.

Did I just call that progress?

The Puritans of seventeenth-century America branded them, that is, the people they punished. Not themselves. What I mean is, yes, they did brand themselves in the sense of branding fellow members of their towns, villages, communities who were evildoers, but they (Oh dear, this “they” and “them” business can get confusing. Sometimes you can’t tell who you are or the others are, who’s us, who’s them, as if in some weird way we [they?] are the same, which isn’t the case. Or is it?) did not brand themselves through personal choice for artistic reasons, as our young people do today, decorating themselves artfully, as is also done with piercings, tattoos, scarification, collars, chains around the neck while playing “slave” and so forth. The Puritans didn’t do that. The collars and chains our forebears (and to be fair, not all of them; some of them were abolitionists) put around others’ necks were not for the purpose of costuming and/or stating a preference or proclivity. The others around whose necks they put these things were not in what we call “mutually consensual” relationships: they were slaves.

Likewise, the branding the Puritans enjoyed was not the personally chosen but rather the imposed-by-others variety, such as burning the letter “B” on a burglar’s forehead.

Not a big leap from there to the scarlet letter “A” emblazoned on a woman’s chest.

While being branded, by the way, one’s brain, heart, back, forehead, neck, or what you will, fries, sizzles, bubbles, burns, blisters and/ or bleeds or what it will. One might try to think oneself away but one cannot turn away. They’ve seen to that. Though maybe if one is lucky, one might black out and not remember much. Though we’ve already established, haven’t we, that one can never forget what happened to one, the place from whence one came, because it stays inside us, in our DNA, a kind of body/moral memory?

On the other hand, you might, if (or before) you black out, see stars.

Are those the stars and stripes we hear so much about forever?

God only knows.

Brian Wilson’s grandfather William “Buddy” Wilson headed back to California in 1914.5 (What is it with these grandfathers, Nathaniel’s and Brian’s both, named William? I guess it’s a common enough name, my brother’s for example. Not my father’s, though, who was Virgil, and who, despite being a man with troubling qualities, was a decent enough guy to not saddle a boy with a name like his. As for our father’s difficult qualities, my brother is more the expert on that than I.) I said William Wilson went “back to” California because when he was young, he, William (“Buddy”), had gone to California with his father, also William (Brian’s great-grandfather?), who tried, in 1904, to move the family from Kansas to California in search of a better life that did not transpire, so the Wilsons returned to the midwest where William pere, not William “Buddy,” resumed work as a plumber and then later William (son? pere?) came back. See what I mean about how everyone gets confused with everyone else? Like we’re all sort of the same person trying the same things and making the same mistakes again and again and again?

Edgar Allan Poe, a contemporary of Nathaniel Hawthorne, wrote a story called “William Wilson.” Actually, he wrote “William Wilson” twice, once in 1839 and then a variation in 1845. Even a fictional William Wilson gets mixed up with other versions of himself! It gets worse. “William Wilson” ends like this: “In me didst thou exist—and, in my death, see by this image, which is thine own, how utterly thou hast murdered thyself.”6

I am you who destroyed yourself. Your dream will be the death of all your kids.

William Wilson went back to California in 1914. He was ambitious, determined, stocky, and a drinker often to the point of violence. He beat his family, particularly his wife. Sometimes his son, Murry, tried to rescue his mother, coming between her and his father, who then hit him, so then he hit his father back, and so on and so forth.

When he grew up, Murry Wilson, Brian’s father, was, like his father Buddy (William), ambitious, determined, stocky and, after he married (Audree Korthof in 1938) and became a father, a drinker often to the point of violence. Not against his wife, though, just his sons. His sons were Brian (born 1942: composer, arranger, producer, dreamer, genius); Dennis (1944: the drummer, the cute one, the sexy one, the one who fought back most, the one who drowned); and Carl (1946: the quiet one, the chubby one, the lead guitar who took over producing the band when Brian dropped out in the late ’60s when he went crazy. Dead of cancer in 1998).

Murry had work during the Depression, when a lot of other people didn’t, and he was proud of that. He always said if you worked hard enough you would succeed in America. His sons remember him shouting, over and over again, and in the vernacular, the Puritan work ethic upon which this great nation was founded: “You’ve got to get in there and kick ass!” Murry moved up the ranks at the Southern California Gas Company to a post in junior administration. After his sons were born and World War II ended, he moved his family to Hawthorne.

It was a move up. He got a better job in administration at Goodyear Tire Rubber Company where, in a perhaps Nathaniel-Hawthorne-not-on-a-good-day, metaphor-like accident, he lost his left eye. (Blind. No perspective. Can’t see past the nose on his face, etc.) Murry left Goodyear (though his sons stayed in its shadow for a while, writing song after song about cars, car tires, burning rubber: “gotta be cool now, power shift here we go”7) to start his own business. He called it A. B. L. E. (Always Better Lasting Equipment), a name the Puritans could have dreamt up, as if a divine prescription for the perfectibility of God’s chosen children always getting better, as if someday, in some New! Improved! beyond we would be better and forever lasting.

Though Murry pushed his boys, often literally, to get what they wanted, as soon as they started getting it, he resented them. Demeaned them. Then he tried to control both what they got and them.

For what Murry had always wanted, ever since he was a boy, was to write hit songs.

But Puritans don’t sing and dance. To do so is to sin.

The dreams of fathers visit sons; the failures and the jealousies as well.

William Hathorne’s son, John, became, in 1683, a deputy to the General Court in Boston. I don’t know if this was before or after 34-year-old john married a 14-year-old girl, their notions of evildoing being somewhat different from ours. (Poor Jerry Lee Lewis! To think he might have fared better as a Puritan!) Anyway, John Hathorne (still no “w” in his name), Nathaniel’s grandfather, “inherited,” in Nathaniel’s (“The Custom House”) words, “the prosecuting spirit, and made himself so conspicuous in the martyrdom of the witches, that their blood may fairly be said to have left a stain upon him,” and, we may conclude with confidence, upon his descendants. For Nathaniel went on to confess, “I, the present writer, as their representative, hereby take shame upon myself for their sakes, and pray that any curse incurred by them—as I have heard, and as the dreary and unprosperous condition of the race for many a long year back, would argue to exist—may now and henceforth be removed.”

John Hathorne certainly could have been cursed, having dispensed most gruesome punishments such as—Oh Christ, let’s not go through all that again; see above, if you must—to persons of all ages. This Hathorne was the one who, during the trials of 1692, condemned the Salem witches to the gallows and to drown.

Fulfill your father’s dreams and he will envy you to death.

You take your father’s sins upon yourself.

A century and some years later, while living at his family home in Salem, Nathaniel Hathorne walked, reclusive and alone, to Gallows Hill, to be among the ghosts of those his ancestors condemned.

Can you remember things you didn’t do but someone else did? Can you get over them for someone else? Can you get over them at all? Can you forgive them?

What if they’re not forgivable?

The Scarlet Letter: A Romance, published in 1850, was mostly written in 1849, the year of the California Gold Rush. As contemporaries of his were heading west again, where they hoped this time to find, if not a spiritual, at least a financial paradise, Nathaniel Hawthorne was looking back at what his forebears had done wrong.

The Scarlet Letter was Hawthorne’s fourth book for adults (he’d also written for kids) and, after the middling successes of his earlier work, he was surprised it did as well as it did.8 The first edition of 2,500 copies sold out in ten days and his publishers had to reprint. In other words, this story of forbidden love was a hit.

In the chapter entitled “The Recognition,” Hester Prynne, condemned to wear the scarlet letter “A” on her dress, is leaving prison with her newborn love child (“Never meant to be!”). Someone, Hawthorne narrates, “the eldest clergyman of Boston, a great scholar,” calls “Hearken unto me, Hester Prynne!” and exhorts her to confess, repent and name the father of her child. This speaker is, like many characters in Hawthorne’s work, based on a real person, in this case a leading Puritan divine, John Wilson (1591-1667).

Look, I’m not saying this Wilson was an ancestor of our California-bound Wilsons. On the other hand, don’t we all believe, as our Puritan ancestors did, that if we go back far enough, we all go back to the same old Adam and Eve?

Brian remembers hearing “Rhapsody in Blue” on a record player when he was two, and loving it.

Murry remembers, sometime before Brian was one, carrying his baby on his shoulders and singing, and Brian imitating perfectly the song: “I just fell in love with him,” he says.

Brian and his brothers sang each other to sleep at night, their three-part harmony angelic, sweet, divine. Their father stood outside their bedroom door and listened, misty-eyed.

He later beat them.

Hawthorne’s father died at sea when he was four. After that, his sister Elizabeth recalled, Nathaniel loved to read. She remembers her six-year-old brother sitting in a corner pretending to read his dead father’s copy of Pilgrim’s Progress.

Brian said he went deaf in one ear when his father beat him.

Half of what he hears he only hears inside his head.

But then he said elsewhere that he was born that way.

No matter who tells the story, the story changes.

Nathaniel hurt his foot when he was nine, in 1813 and, incapacitated, read even more. He walked with a limp, self-consciously. He wrote both to reveal and to hide. From “The Custom House”:

It is scarcely decorous… to speak at all, even where we speak impersonally…. thoughts are often frozen and utterance benumbed … we may prate of the circumstances that lie around us, and even of ourself, but still keep the inmost Me behind its veil.

Half of what he said he only said inside his head.

Though it didn’t appear on an album until 1963, the first ballad Brian ever wrote, “Surfer Girl,” was inspired by “When You Wish Upon a Star,” the song Jiminy Cricket sings to the wooden toy who wants to be a boy, Pinocchio. He composed this song while driving in a car on Hawthorne Boulevard.

After his father died the family moved down a social rung, and Nathaniel and his mother and sisters moved into his mother’s family’s many-gabled home. They paid rent and board, and were polite, impermanent and nervous hangers-on.

He was a child set apart, an oddity, a troubled boy inside a room inside a seven-gabled house.

Murry bought a professional-quality organ so he and Audree could play duets. Though Brian played piano and listened to records, Murry taunted him: No discipline. A jackass. Lazy.

Nathaniel’s father turned his back on the traditional professions of the Hathorne men (judges, soldiers, murderers) by going to sea, and died when he was young. How could Nathaniel not turn his back too?

Because everyone is confused with everyone else. Everyone’s sort of the same person making the same mistakes again. Not getting and not getting over it. Not better, though lasting forever, alas.

When he was 14, Brian went to Hawthorne High. He was tall, fun-loving, sweet and a fantastic baseball player. He began spending time at his buddies’ houses listening to records and the radio, and getting away from Murry.

When he was 16, Nathaniel started a family newspaper called the Spectator, which he always was, looking in from the outside.

When he was 16, Brian was singing his own arrangements of the Four Freshman, Bill Haley and Elvis, with friends at school and with brothers and cousins at family gatherings.

Nathaniel went to Bowdoin College because it was near where some relatives lived in Maine and was inexpensive. There, though he became friends with future president Franklin Pierce and a lifelong, cigar-smoking Democrat, he was loath to study anything that would lead to a conventional profession.

Brian went to Hawthorne High where he gave his first quasi-public performance, an adaptation of “Hully Gully” turned into a campaign song for a friend who was running for student government. After Hawthorne High, Brian went to El Camino Junior College where he studied music and psychology until he dropped out because one day his little brother Dennis came home talking about surfing and Brian decided to write a song about that. A few weekends later, the Wilson parents went to Mexico for a holiday and left the boys with money for food. The brothers and their folk-singing friend, Al Jardine, spent this money, and some lent to them by Al’s mom, on renting a mic, an amp and a standup bass. Then, with cousin Mike Love, they spent the weekend rehearsing “Surfin”’ in hopes of making a demo tape. When Murry came home, he yelled at them for having spent the money the way they had. They begged him to listen to the song, and when he heard it he thought that they might have a hit and promptly appointed himself the manager of the Wilson family band. At first they were called “The Pendeltons,” after the striped shirts the boys wore.

Nathaniel Hawthorne was a natty dresser.

Murry worked hard to cultivate publishing and radio contacts for the band, but he also humiliated and fought with his sons, more physically with Dennis and psychologically, in the studio, with Brian. In 1965 the sons had to fire their father from the band.

I’m bugged at my ol’ man

’cause he’s makin’ me stay in my own room.

Darn my dad …

I wish I could see outside

but he’s tacked up boards on my window…

Gosh it’s dark…

— “I’m Bugged At My Ol’ Man” (Brian Wilson, from Summer Days and Summer Nights)

The Beach Boys could not, however, fire their father from being their father.

Nathaniel tried to. When he was 21, he changed the spelling of his surname, adding the “w.” As if with this single letter he could separate himself from them. As if a single letter, as if a “B” branded on a burglar’s face, a scarlet “A” across a woman’s breast, could tell us who you are.

Brian wrote a string of hits. He was the native genius, American music’s answer to the sophisticated pop of the British Invasion. While Paul Revere and the Raiders could spoof, with their tights and Colonial-Era-looking jackets, a rebuff of the English, they ended up the butts of jokes. (Remember their Midnight Ride?9) Brian and the California sound he created not only rivaled the Beatles, Animals and Stones (who, after all, had created their sound by imitating American blues and rockabilly) on the charts, he also gained the admiration of classical composers like Leonard Bernstein. Everyone wanted to work with Brian Wilson in the studio. He treated the studio as an instrument.

Nathaniel’s books were a string of hits, much-read and well-reviewed. He was revered at a time his countrymen were trying to create a particularly American culture (The Hudson River painters, Melville, Whitman, Poe), distinct from the English and European models they’d been handed. He treated his own, his family’s and our nation’s history as Romance. A story we cannot escape. A myth that will not ever have an end.

He saw himself as set apart, an oddity, a wounded boy inside a room, a gabled house, a continent of sons and daughters doomed.

Gosh, it’s dark.

Brian Wilson kept to his house for years. After the triumph of Pet Sounds (1966), he pulled the plug on what would have been his masterpiece, Smile, and lay in bed. He took a lot of drugs and ate a lot of hamburgers, ignored his wife and daughters and got fat. Sometimes in bed or at his piano and in his filthy pajamas, he wrote little songs about health food, feeling great and love. When he did leave his home, he wandered, long-haired, filthy-bearded, unwashed, weird. Everyone thought he was crazy.

Nathaniel Hawthorne kept to his house for years. After graduating from Bowdoin, he returned to ghost-filled Salem, to live in his family home. (Melville later called him “Mr. Noble Melancholy.”) He wrote in isolation and published his first novel anonymously (there was something about his father’s name that galled him) and at his own expense. Around this time he also added the “w” to his name. He soon pulled the plug on his own career by burning every copy of the novel he could find. For the next ten or so years, he lived reclusively with his mother and sisters, stayed in his room and wrote, tore up what he wrote, and published, anonymously, little stories. When he walked to the graves of people who’d been murdered by his Hathorne forbears, he walked alone. He was evasive, skittish, melancholy, weird. Everyone thought he was crazy.

But maybe it was the world that was crazy then. Mid-century America was not only the land of transcendentalism but also of Transcendental Meditation, of spiritualism and the Jesus movement, of mesmerism and the Manson Family, Ouija boards and table rapping, good vibrations and animal magnetism. Millennial cults and Back to the Land-ers, the California Gold Rush and the Summer of Love, of railroads and rocket ships, Seneca Falls and Ms. magazine, the Civil War and civil rights, assassinations of presidents, and Edgar Allan Poe.

He wrote The Scarlet Letter the year of the California Gold Rush. He wrote “The Warmth of the Sun” after the assassination of Kennedy. An elegy, a fantasy. A warning, a regret.

He lived beside and walked along the shore of the Atlantic, the Pacific, but couldn’t keep his sights out there alone. He looked back where he had come from and toward the waves his fathers rode, the waves his brothers tried to ride. He walked among the graves his fathers and his brothers filled.

He was an innocent, an always-boy. A skeptic, never-boy. Forever wise, forever sad. Forever wanting to forgive and to pretend it wasn’t bad and getting worse. Forever going back as if remembering or taking on, undoing what the fathers did, the fathers’ sins, our own. He was before and past and utterly of his time.

In 1969 he wrote, or rather cowrote, a song:

Time will not wait for me

Time is my destiny …

I can break away from that lonely life

and do what I wanna do

my world is new

Where the shackles that have held me down

I’m gonna make way for each happy day.

—from “Break Away” (B. Wilson - R. Dunbar)

For Hawthorne time was always past and destiny. We are always looking back. What happened? Why? We came from there. How do we get away? Forgive or be forgiven? His words were his attempts to break away.

Brian Wilson stayed an innocent. For him time is, as it is for all westward travelers, the future.10 In the future you can start over again. Despite the “shackles” (remember them?) that held him as they held his Puritan forebears. But he still hopes, as if one can, “my world is new.”

As if the fathers’ sins can wash away.

The happy “Break Away” song was credited to Brian and a collaborator named Reggie Dunbar. Reggie Dunbar was a pseudonym used by Murry, Brian’s father.

A son forgives a father’s sins.

What mercy has the child for the man.