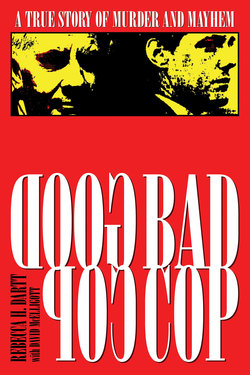

Читать книгу Good Cop/Bad Cop - Rebecca Cofer - Dartt - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеTWO

MICHAEL ANTHONY KINGE A/K/A TONY TURNER

That afternoon Joanna White got out of bed around two o’clock, her normal routine after working the night shift at Ithacare, a nursing home in downtown Ithaca. It felt chilly in the apartment in spite of the kerosene heater that her boyfriend, Tony Turner, had put in. Because they were so far behind on their gas and electric bills. The landlady, Mary Tilley, didn’t allow kerosene, but they figured what she didn’t know wouldn’t hurt her.

They had an arrangement with Tilley to help pay their monthly rent of $396; every time Tony cleaned her rental apartments, she deducted the rent they owed her from his pay check.

He had signed an agreement with New York State Electric and Gas Company that morning, stating he would make twenty-eight dollar monthly payments for three months to catch up on unpaid bills. Otherwise, the electricity in their apartment would be disconnected. But he didn’t have enough cash in the bank yet to mail a check with the agreement.

Tony’s last steady job, cleaning movie theaters at the Pyramid Mall had ended several months earlier after he refused to pick off chewing gum stuck to the back of theater seats. He had been working for his friend Ron Callee, a neighbor he hung out with when he lived in Locke, a rural hamlet north of Ithaca. Callee told him he couldn’t take his slipshod work any longer. Refusing to clean up the gum was the last straw.

As Joanna boiled water for coffee, Tony gave her their one-year-old son to hold and said he wanted her to give him a ride in a little while, so he could “go to work”. By work Tony meant going out to rob somebody. He always described those excursions as work. She never asked any questions.

Joanna had met Tony Turner, an assumed name he used after moving upstate, at a downtown bar in 1980. He was ready for a new start. Tony was on parole from Fishkill State Prison, having served one year of a three-year sentence for armed robbery (a fact in the beginning he kept from Joanna). Tony’s looks appealed to her: His five foot, eight inches tall lean, lanky expressible body, Afro-hair style, glowing ebony-skin was very different from the small town guys she knew. His deep-set black eyes seemed to look through her. He came from New York City and flaunted an arrogant, “I’ve seen and done it all” attitude. He was a mix of soft-spoken charm with an explosive fuse that went off abruptly. There was a magnetic wildness about him that both scared and excited her.

In those days there was no doubt Tony was a charmer whose mild mannered ways made people want to help him.

Tony was originally named Michael Anthony Kinge and called Michael until he started using an alias when he moved upstate to escape the law. As a kid, Michael had been fastidious about his appearance. When he was twelve, he asked his mother to teach him how to sew his own clothes. He learned the craft and from then on made most of his clothes. In addition to his handiness with a needle, Tony like to read and take small household objects apart and put them back together. His mother marveled at her son’s abilities and since a toddler, Michael could smile his way out of trouble. His sister wasn’t so fortunate; from early on a rivalry existed between brother and sister that developed into full blown hostility by the time they were adolescents.

With no man in the household and no financial support from her ex-husband, Shirley was away from home working to support the family a good deal of the day and night while her kids were growing up. She had met her husband, Robert Kinge, at a lunch counter in Newark while she was working for the government as a key punch operator in 1954. They got married when she was four months pregnant and after their daughter, Ga-brielle, was bom. the marriage began to sour. Shirley went home to her mother after Robert slapped her for something she said that he felt insulted his manhood. Her mother said he wasn’t any good anyway. They got back together for a few months until Michael was bom a year after Gabrielle. The next time Shirley left it was for good. She couldn’t stand to be bossed around. Shirley went home to her mother, Sally Reese. Shirley and the children lived with her until 1963 when she moved to New York City.

While they lived there Shirley worked hard but she barely earned enough as a bus information clerk at New York City’s Port Authority Building to pay the rent for their apartment on the upper westside of Manhattan. It was an integrated, middle-class neighborhood when they moved there and Shirley liked it that way. She wanted to move up the social and economic ladder. She was an independent, articulate woman with a hard edge who was always getting a raw deal, she felt. Boy friends stayed around for as long as they got what they wanted. At least, she ended up with some nice clothes and fur coats. She was taken in by Manhattan’s penchant for fashion. Having expensive clothes and jewelry became important to her.

Shirley was used to lying about her son Michael. She’d been covering up for him since he first told her he didn’t feel like going to school when he was nine or ten years old. It was easier to give in. The kid was a real charmer and she didn’t have any man around to show authority, so she had to just glide through and try to rock the boat as little as possible. There was enough friction between Michael and his sister already. She didn’t want any more problems to deal with.

Michael didn’t know his father as he was growing up. He came around a few times while they lived in Newark, but Shirley and her mother put up such a fuss when they saw him that he stopped coming.

One day Michael bumped into his father on a Newark city bus. He wouldn’t have known him, but Robert Kinge recognized his son. It was the last time they saw each other.

The neighborhood had changed; the more affluent moved out and poorer blacks and Hispanics moved in. Street crime was on the rise. It became tougher for Shirley to cope. She was tired of a job that wasn’t going anywhere; she was often late or absent from work.

Later Shirley tried to forget those years in the city. Gabrielle started running away from home when she was barely a teenager, Michael was always in trouble and the neighborhood was rotting with crime. Their apartment was broken into three times.

By the time Michael reached junior high school he missed as many days as he attended. School absence was a well-entrenched pattern by then. School work didn’t interest him; he considered teachers and school kids dumb; his mother was the only smart one. Occasionally he’d put on his charm and help with after school projects. But more frequently he was an unresponsive loner who could lose his temper when things didn’t go his way. His short fuse was noted in elementary school by a teacher who reported that Michael lacked self-control. He was the last to finish class assignments, an underachiever who routinely performed below his scores on aptitude and intelligence tests. Michael was fifteen when he entered the new alternate Westside High School designed for kids at risk.

Michael was adept at using his charm to flirt with girls. He often got his way. At sixteen he fell for a white girl from a rich family. Her parents scorned her for going out with a black boy, but she defied them and continued to see Michael. When she discovered she was pregnant, the situation overwhelmed her. She couldn’t face her family with that kind of news. In desperation she killed herself.

The following January, Michael was arrested for burglary and sent to Rikers Island for sixty days. Westside High’s secretary, who was as much a social worker as an administrator, was concerned that no one was visiting him in prison. She arranged for a school volunteer to see him several times during his incarceration.

Michael dropped out of school at seventeen and joined the Marine Corps with his mother’s blessing. After his girlfriend’s suicide, Michael wouldn’t even look at black girls. No one was going to dictate to him who lie would see and what he did. His girlfriend’s suicide seemed to harden his determination to defy the rules. And he began to wear his anger as a badge of honor.

At the time he met Joanna in 1980. he was out on parole from Fishkill prison, having served one year of the three-year sentence for a crime he committed in New York City in 1975. He had skipped town when convicted in 1975 on an armed robbery charge and not until 1978 when he applied for a $1,300 bank loan using a bogus name and Social Security number in Auburn. New York, did the law catch up with him. After he served eight months in Cayuga County jail for the loan fraud, he was moved to Fishkill prison in Clinton, New York.

Tony liked Joanna well enough to make an effort at trying to do something that could lead to a good paying job. He attended Cayuga County Community College in Auburn, graduating with a business degree in 1982. He had lied on the college application form about his “honorable discharge” from the Marines; he was actually court-martialed in July 1974 when stationed at Okinawa, Japan, for refusing to obey his commanding officer to clean latrines and for stealing four cartons of Winston cigarettes worth about $5. He was ordered to forfeit $400 in pay and was given thirty-five days at hard labor. He’d been trained as a mortarman during his brief tenure in the Marines.

It was against New York State law to ask about an applicant’s criminal record on the college admissions form.

Tony applied to large and small business firms in the area. He dressed in a business suit and imagined he was going somewhere, now that he had a degree. But he was rejected wherever he applied. This was a time, during an economic recession, when many firms had a hiring freeze on. but Tony took it personally. He felt they didn’t hire him because he was black and he was convinced that companies would investigate and find out about his criminal record.

Five months after graduation, he was arrested in New York City with a loaded firearm.

Like his mother, Tony also aspired to material things, good things, and attractive companions. In his case he seemed to care little about how he got them.

Joanna found out later that Tony only went out with white women. He was proud of his success with them; they enhanced his self-image and gave him a sense of power. Joanna turned him on with her petite good looks and long, light brown hair. And she liked a good time. Soon he convinced her to drive to New York. It was an exciting adventure for a rural girl whose idea of wild up to then was getting drunk and smoking a little pot. They slept in the car most of the day and at night.

Joanna worked as a go-go girl in a striptease joint. Tony was doing stickups at grocery and liquor stores. After Tony had robbed enough cash and loot to last a while, he’d buy drugs at a good price on the street. The big city capers ended when Tony was arrested in the city on an armed robbery charge one night. He didn’t appear in court the next day, so a bench warrant was issued in the name of Michael Kinge.

Joanna’s father disowned her when she started dating Tony. He was a proud redneck who didn’t like blacks; the idea of his daughter going out with one infuriated him.

It was not too surprising that Joanna went against the taboo so strongly held by her father. It was her way of saying, “I am me and I’ll run my own life.” After her parent’s divorce, she had lived with her mother and sisters in West Village, a low-income housing project on Ithaca’s west hill. They didn’t approve of Joanna going out with a black man either. The relationship eventually caused so much dissension in the family that Joanna moved out and got a room of her own downtown.

Not long afterward, she and Tony moved in together. She was game for almost anything during the first years they were together and had little to do with her family.

But then five years later, her son James was bom. Having a child changed Joanna who wanted a calmer more secure life. And Tony, never a patient man, yelled at her in a swearing rage these days when nothing was going right.

By now Tony was always looking for a quick hit for cash. Sometimes he got grandiose about it. He talked of ripping off a money-rich drug dealer or a Mafia bookie. Then he wouldn’t have to worry about cops. He hated cops. He told Joanna he wouldn’t go back in-he”d shoot it out first. His dream was to wear a bulletproof vest and goggles and ride a motorcycle with a headset in the helmet, so he could track police movements on scanners. Sometimes he dressed in his black Ninja costume and practiced sneaking around the neighborhood, just to see if he could creep around and not be detected.

Tony couldn’t stand the feeling of being controlled by other people. That’s why he couldn’t hold down a job for long. He thought he was smarter than every body else, so he decided the only way to get what he wanted was to operate outside the system. He had formed a fantasy world where he could control others (the women in his life who did his bidding) and exert a kind of power that made him feel powerful. To keep control, he made sure his women knew that violence or the threat of it was close at hand. Tony had been a student of violence for years.

His favorite movies were packed with violence. He never tired of watching “Lethal Weapon.” He dreamed about owning a Berreta because that was the weapon of choice Clint Eastwood had made so famous. He read paperback accounts of vigilante heroes, like The Executioner series, where the hero takes the law in his own hands and guns down drug dealers with powerful weapons. Books like Improvised Weapons of the American Underground gave him ideas for his workshop. He bought hard-core pornographic magazines, especially ones that covered bizarre and violent sex.

Although her father still refused to see her, Joanne reestablished contact with her mother after the birth of her son. Two months earlier Joanna had told her mother she wanted to move out. Tony was depressed, couldn’t sleep, had migraine headaches and he exploded in anger at the slightest thing; she was walking a tightrope with him.

It was nervous energy and worry about her son that kept Joanna going. She raced around all day before leaving for work at the nursing home, and on the job she kept going with few breaks. Being able to smoke was one of the advantages of working the night shift. Because of anxiety she chain-smoked. She couldn’t go long without a cigarette. Thelma Thomas the aide who shared the midnight shift with her, a grandmotherly older woman, noticed how thin Joanna was getting and said, “Just look at you, you’d better slow down and eat more.”

Joanna nodded but hadn’t replied.

As for Tony, even smoking pot didn’t relieve his jitters for long now. He was hooked on grass and no matter how strapped he was for funds, he found enough to buy a nickel bag, often borrowing from his mother Shirley or grandmother. He tried to grow marijuana plants in the apartment, but gave up when their electric bills nearly doubled. It had been a while since Tony used acid. The local supply fluctuated and when it was scarce, the dealer marked the drug up to the point Tony thought it wasn’t worth it. Drug busts were on the increase in the area.

Because Joanna was alarmed by Tony’s behavior, she frequently left the baby with Tony’s grandmother Sallie Reese when she went to work at night. Mrs. Reese, an independent woman had few attachments. The reason she took care of Tony’s child had more to do with her own daughter Shirley than her interest in the baby. She was committed to her daughter and did anything to help her. Sallie had decided to retire and moved from Newark, New Jersey, where she had lived most of her life, and bought an old farmhouse on a two and a half acre property for $13,500 in Cayuga County. She wanted to escape the city’s noise and crime and live an easy life. But she discovered it was expensive living in an old country house. To make ends meet she had to go back to work as a live-in nanny and housekeeper with an Ithaca family. She sold the property two years later and moved closer to her daughter.

Now that she was finally retired, her biggest pleasure was watching television in peace and quiet. She made sure baby-sitting her great-grandson didn’t get in the way of that. The baby slept or played in the crib in the bedroom next to hers while she reclined in bed and looked at television movies and her favorite programs.

Meanwhile things for Tony and Joanna went from bad to worse. They were behind in their rent and hadn’t paid gas and electric bills for two months. The landlady had just served them their third eviction notice. Finally Joanna asked her mother if she and Jimmy could stay with her for a little while. The situation had to be pretty bad, because Joanna would rather walk through fire than ask for help from her family. She hated to admit she couldn’t go it alone. Her mother said no, it wouldn’t work out at their house because her husband (Joanna’s new stepfather) couldn’t stand the noise that babies made. She gave Joanna four hundred dollars to pay the rent.

On the Friday afternoon of December 22 Tony and Joanna took their son over to Tony’s mother and grandmother who lived on the other side of the duplex. Hie house they shared was on the dirt and gravel stretch of Etna Road that ran close to Tompkins County Airport and parallel to Route 13. the north-south highway out of Ithaca. They liked the isolation of the place. The few scattered houses were situated among thick woods on both sides of the road. A ranch house and a collapsing bam were cross from them and around the comer on the other side were two more frame duplexes of the same design, also owned by Mary Tilley.

Farther down the road was an old logging trail. A stripped-down, yellow flatbed truck sat on cinder blocks in their front yard. The mixture of well-kept and shabby properties on one road was common in the area, where zoning laws either didn’t exist or weren’t enforced. The location fit their unsociable lives and their shaky finances; although on rare occasions a friend of Tony’s stopped by, the women never had company. They let Tony’s lifestyle set the tone for all of them.

The duplex looked cheap and rundown. It was made with gray, vertical board and baton siding, a flat roof, aluminum storm doors, and no windows on either side of the building. Each apartment in the duplex had three bedrooms upstairs with two rooms and a kitchen downstairs. But with so little square footage to each room, the place seemed crowded.

Walking outside they couldn’t help but notice the bad weather. Neither said anything about it. Joanna had to get to work and Tony was intent on leaving as quickly as possible and didn’t care about ice and snow.

Joanna got in the driver’s seat of the 1977 blue Ford pickup while Tony put a bicycle in the back. A few months before, he had gone downtown and had come home with the black Nasbar. Joanna didn’t ask him what had happened. She knew he’d say it wasn’t any of her business, and she really didn’t want to know anyway.

Then Tony told Joanna to drive to Turkey Hill Road. He didn’t say what his destination was. She took his silence for granted. He was in one of his dark moods and that meant the only talking he did was when he barked out orders and she did as she was told. She had to drive slowly, because of the snow buildup on the road. They took back roads as they generally did. Tony insisted they stay off the main highways when he was in the truck or in his mother’s car. There was less chance of meeting cops on secondary roads.

They passed a few houses and long stretches of cut-down cornfields frozen to the ground. When they reached the bottom of Turkey Hill, he told her to turn left. She didn’t know the name of the road. They went a few miles and turned right. After a short distance Tony told her to stop before a bridge. They were on Genung Road. He got the bicycle out of the back and slung a knapsack over his shoulder. He usually had a gun in it since he always wanted to protect himself. He had on a dark blue parka with a fur-lined hood.

Joanna turned the truck around and as she drove away, she saw Tony in the rearview mirror, standing up as he pedaled the bike uphill toward Ellis Hollow Road. It was 3:20 P.M. The temperature was ten degrees above zero and falling.